Girl Is A Half-formed Thing by Eimear McBride

Girl Is A Half-formed Thing

Girl Is A Half-formed Thing

by Eimear McBride

Galley Beggar Press, 2013

240 pages / Buy from Amazon or Gallery Beggar Press

We were on the sofa one evening and I was typically glued to my book when my boyfriend leaned over and read aloud: Feel the roast of it. Like sunburn. Like a hot sunstroke. Like globs dropping in. Through my hair. Spat skin with it. Blank my eyes the dazzle. Huge shatter. Me who is just new. Fallen out of the sky. What. Then he rolled his eyes and asked me how the hell I was following that. The TV was on. The lamp was making a weird buzzing noise. The dog was loudly slurping her bits. To be perfectly honest, I’ve no idea how I was following A Girl Is A Half-formed Thing. The language is extravagantly jumbled. The pace is disconcertingly broken. The chain of events is peripatetic. Nevertheless, it had somehow managed to draw me in, to hold me. Each tiny sentence was blaring louder than the TV, louder than the buzzing lamp, louder than the slurping. And I understood perfectly; I knew exactly what was happening.

Last week, A Girl Is A Half-formed Thing won the inaugural Goldsmiths Prize for fiction. The prize, initiated by Goldsmiths University of London, is unlike any other I’m aware of in the UK. According to the official website, it has been established ‘to reward fiction that breaks the mould or opens up new possibilities for the novel form,’ celebrating ‘creative daring’ and ‘the spirit of invention.’ Eimear McBride might have instigated her debut novel intentionally for the prize, had it not been written almost a decade ago. The story of the book’s journey to publication makes the author’s victory all the more significant, albeit bittersweet. Originally rejected by publishers, presumably on the basis that it was too strange, too difficult, it was ultimately taken up by Galley Beggar Press, a small, independent publishing house. In the months which followed its release this summer, A Girl Is A Half-formed Thing has been reviewed to widespread acclaim. McBride has been variously declared a genius and her writing compared to James Joyce and Samuel Beckett.

The book begins with childhood in a gloomy and petty-minded version of rural Ireland. The half-formed girl of the title narrates. She is a reckless, fractious person, and the story is driven by her anger. She has no father to speak of and her mother is a pious, resentful woman. It is the strength of the bond with her elder brother that gives the half-formed girl her humanity. It is to him that every impassioned sentence is directed, even though it’s not with him that she is angry. Took me hot hand to the bathroom then and water on my face. Gentle wiping, saying there now it’s alright. Cleaned blood from me like I saw at school. Head back gulping the thickly flow. Now, you say, we’ll be good. Now we’ll do what we are told. Maybe she’ll forgive us if we’ll be good. Alright? We’ll be good now. After surviving a brain tumour in early boyhood, he is condemned as a dullard, his options stealthily shrinking as the years slip past. Handicap. Handicap. One from back gets the ball. Kicks and aims. It strikes your face. Bleared with mud. And knock you over. Laughter. Laughter. He is the character I cared about, the one I wanted to read on for. The story continues into the narrator’s twentieth year, her voice growing incrementally strained. The end is incalculably devastating.

I went to art school. (This may seem like a somewhat circuitous way of attempting to make a point but please bear with me.) I made colourful, wooden things, but my best friend made remarkably distressing video pieces. She’d perform actions that hurt, and film them. These actions weren’t necessarily physically painful, even still they proved excruciating to sit and watch. For example, in one piece, she used her chin to drag her naked body across a flat-weave carpet. In another, she manically licked tiny stickers off a white wall, and in another again, she bound her hand and forearm in elastic bands and then scrabbled to remove them using only the bound hand. Once I challenged her on what exactly was to be achieved by creating such unsettling work. So long as I made you feel something, she said. Feeling uncomfortable is better than feeling nothing at all. I recalled this conversation many times while reading McBride’s debut.

To say that I ‘enjoyed’ A Girl Is A Half-formed Thing would be lying. I thought it was a spectacular book, but it made me feel thoroughly horrible. McBride won the Goldsmiths Prize last week because, in the words of one of the judges, her debut is ‘boldly original’ and ‘will stimulate a much wider debate about the novel.’ It certainly encouraged me to contemplate the boundaries of traditional prose, and to reconsider the rules of grammar and punctuation. But the book’s greatest feat is that it outstrips the intellect and becomes foremost visceral in effect, a matter of the stomach and soul instead.

***

Sara Baume is a writer, of sorts. Her reviews, interviews, articles and stories are published occasionally both online and in print. She lives on the south coast of Ireland and can be found at www.sarabaume.wordpress.com

December 16th, 2013 / 12:00 pm

With the Animals

With the Animals

With the Animals

by Noëlle Revaz

Translated by W. Donald Wilson

Dalkey Archive, May 2012

232 pages / $22.95 Hardback; $14.95 Paperback. Buy from Dalkey Archive or Amazon

Originally published in French as Rapport aux bêtes by Gallimard, Paris, 2002

Sometimes a book comes along that is written in a voice so bizarre and so steadfast, so almost chant-like, that it worms inside my head and plays over and over until I find myself unconsciously putting its somewhat archaic words and phrases to everyday use. Whilst reading With The Animals, I am all of a sudden “canoodling”, “yammering”, “palavering” and “gallivanting” through a world furnished with “snot-rags” and “flyspecks”, “gizmos” and “critters.”

With The Animals is the second novel by Franco-Swiss author, Noëlle Revaz, and the voice from which I am stealing is that of Paul: a middle-aged dairy farmer, husband to Vulva and father of “six brats at least.” Paul is a hardworking, hard-drinking, hardhearted man, and his is a life of self-inflicted hardship. Paul is all passion before sense, all anger and hunger and lust. If there are any crumbs of true affection in his shrivelled turd of a heart, then every last one is reserved for his cattle. “Yet I know what it feels like, the way it is when you love”, he says, “you keep squying at her and sighing, you have the everlasting fear something bad might occur to damage her about the horns or make you call the vet.” Paul treats his herd with a tenderness never extended toward his human family. The children have presence only in passing: they idle around the farmyard, they whisper to one another in their beds at night, they skitter instinctively from their father’s path whenever he approaches. At one point, Paul boasts how “all them cows, I know them and I have their names by heart. I can tell when they was born, what diseases they’ve had, and their mother’s name.” Whereas on the subject of his offspring, he is quick to confess how he’s “never able to take to them nor put their names on each.”

June 22nd, 2012 / 12:00 pm

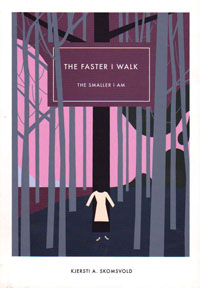

The Faster I Walk, The Smaller I Am

The Faster I Walk, The Smaller I Am

The Faster I Walk, The Smaller I Am

By Kjersti A. Skomsvold

Translated by Kerri A. Pierce

Dalkey Archive Press, 2011

147 pages / $17.95 Buy from Dalkey

Originally published in Norwegian as Jo Fortere Jeg GÂr, Jo Mindre Er Jeg by Forlaget Oktober A/S, 2009

Although I know I shouldn’t, sometimes I judge a book by its title.

At first glance, The Faster I Walk, The Smaller I Am might suggest some kind of self-help manual advocating weight loss by means of low-intensity cardiovascular exercise. But putting the title aside and judging instead from the book’s front cover, (something else I know I shouldn’t do,) it’s clear this could never turn out to be the case. The copy I have, the hardback Dalkey Archive Press 2011 translation, sports artwork reminiscent of a Marcel Dzama painting. In a forest of leafless trees against pink-purple sky there is a woman standing with her back to a trunk, iniscernible save for her white dress and white shoes. The woman turns out to be Mathea Martinsen, and the title turns out to be a reference to Einstein’s theory of relativity, and the book’s content turns out to be a candid portrayal of losses far greater than that of a few inches around the waistline.

Skomsvold writes from the point of view of the front cover’s indiscernible woman. Mathea is childless, widowed and “almost a hundred, just a stone’s throw away.” All of her life, she’s been overlooked. “The spun bottle never pointed at me, the neighborhood kids never found me when we played hide-and-seek, and I never found the almond in the pudding at Christmas…” Now she lives alone in the same apartment block in Haugerud, a suburb of Oslo, where she has spent all her married life. Mathea likes to knit ear-warmers, read the obituaries and start new rolls of toilet paper. She is surprisingly proud, yet appallingly lonely – so lonely she listens to the distant sound of sirens and wishes they were coming for her, so lonely her only sense of fellowship is achieved by buying the same groceries as strangers she passes in the aisles of the local store.

March 23rd, 2012 / 1:00 pm

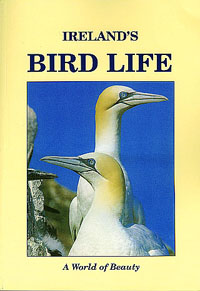

Ireland’s Bird Life: A World of Beauty

Ireland’s Bird Life: A World of Beauty

Ireland’s Bird Life: A World of Beauty

Edited by Matt Murphy and Susan Murphy

Text by Richard Lansdown

Images by Richard Mills

Sherkin Island Marine Station Publications, 1994

160 pages / Abe Books

There is a twitcher out on the seafront.

The seafront must be a few miles long altogether – stretching from the oil refinery past the power-station all the way to the saltwater lake, and then the woods. Some days the twitcher will be outside our house where the waders dabble in the mud for lugworm and shellfish. Other days he’ll be down by the saltwater lake where the wigeons and shovelers compete for stale breadcrumbs.

My boyfriend thinks there are a couple of different twitchers, but I know there’s just the one.

He is a little kingfisher of a man with long beak and speckled brow, and when he perches on the folding-stool with his face fastened into a pair of binoculars, his elbows jut out at each side like a stubby wingspan. Although it’s hard to tell through all his cold weather clothes-wear, I guess he is about seventy.

I am certainly interested in nature but it’s other people that interest me the most.

February 6th, 2012 / 12:00 pm