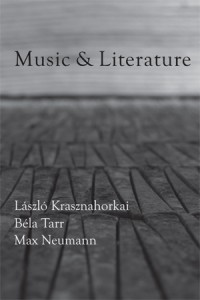

Interview with Taylor Davis-Van Atta, Editor-in-Chief of Music & Literature

I was recently introduced to the fantastic journal Music & Literature via their 2nd issue focusing on Hungarian writer László Krasznahorkai and filmmaker Béla Tarr, both obsessions of mine. I was excited to have the opportunity to ask Editor-in-Chief Taylor Davis-Van Atta about the project.

I was recently introduced to the fantastic journal Music & Literature via their 2nd issue focusing on Hungarian writer László Krasznahorkai and filmmaker Béla Tarr, both obsessions of mine. I was excited to have the opportunity to ask Editor-in-Chief Taylor Davis-Van Atta about the project.

(From their website:

Music & Literature is a 501(c)(3) charitable organization dedicated to publishing excellent new literature on and by under-represented artists from around the world. Each issue of Music & Literature assembles an international group of critics and writers in celebration of three featured artists whose work has yet to reach its deserved audience. Through in-depth essays, appreciations, interviews, and previously unpublished work by the featured artists, Music & Literature offers readers comprehensive coverage of each artist’s entire career while actively promoting their work to other editors and publishers around the world. Published as print editions (and soon to be offered as digital editions as well), issues of Music & Literature are designed to meet the immediate needs of modern readers while enduring and becoming permanent resources for future generations of readers, scholars, and artists.)

***

Janice Lee: Music & Literature is an exciting new project. Can you talk a bit about its inception and inspiration? I’m curious too about the very simple but semi-mysterious title? (For example, Issue 2 doesn’t seem to have very much music but a bit on film and photography.)

Taylor Davis-Van Atta: I sometimes think of Music & Literature as an act of frustration. It’s certainly a response to the longstanding shortage of high-quality arts coverage in English and, more recently, the austerity and cutting-back of coverage in our so-called traditional media. A lot of the arts review activity cut from newspapers has migrated online and proliferated there, and I often hear people say what a great thing this digital groundswell is, but I have to admit I find myself on the other side of this one… For the moment I’ll speak strictly about books and book coverage: while I can appreciate the benefits of a vast online book culture (broad coverage in terms of numbers of books, plenty of opportunity for young critics to strengthen their skills, etc.), the overall effect, it seems to me, is that a lot of attention may be drawn to the fact that a new book exists, but very little of quality and depth is actually written about the book. Add to this that discerning book and arts criticism has, for some time, been increasingly sequestered to the realm of academic journals—which are written and edited by academics, for academics—and I would argue that there is a missing class of accessible, smart, enjoyable critical literature available today to people who really love and wish to engage deeply with contemporary art.

All of this is just general talk, but maybe what I’m driving at (if anything) is this: if we agree that great art is inexhaustible, I think we need a class of literature that meaningfully engages that art, that offers new in-roads and allows us to explore the dark, recessed chambers of a book or symphony or film so we might see and experience it anew—or that simply provides the opportunity for us to discover an artist or piece of art we haven’t encountered before. This is the need we’re trying to address with Music & Literature. None of this is to say there aren’t venues—print and online—providing high-quality critical literature (I’ll not name names, since I’m bound to forget a few), but none that I’m aware of focus so intently as Music & Literature on providing art lovers with comprehensive, deep, and creative coverage of artists’ entire careers.

Since its inception, I have considered Music & Literature to be an arts magazine, broadly defined; that is to say, I’m interested in publishing all forms of art (and work about all forms of art)—and the more cross-pollination the better. While Issue 1 features two writers (Micheline Aharonian Marcom and Hubert Selby, Jr.) and a composer (Arvo Pärt), and Issue 2 features two giants of Hungarian art (writer László Krasznahorkai and filmmaker Béla Tarr) and a painter (Max Neumann), in each issue (and in future issues) readers will find, say, Noh theatre being discussed alongside the architectural nature of graphic scores, the musicality of an author’s prose discussed alongside the literary implications of a painting, and so forth. Though we chose not to feature a composer in Issue 2, the volume nonetheless contains quite a lot of musical material, including one of Krasznahorkai’s translators, George Szirtes, on the musical complexities of Krasznahorkai’s prose and the difficult pleasures of rendering them into English, as well as a discussion of opera and the nature of evil between Krasznahorkai and composer Péter Eötvös, and more… All forms of art are in constant dialogue with one another, and, for the individual, the experience of great art is the same regardless of the form that art takes: pleasure. For example, we marvel at the ingenuity of architects who reinvent space and encounter, but wither in buildings and structures that create anxiety. It doesn’t take much to intuit the parallels between uninspired architecture and uncreative music, for instance, because all art forms exercise our critical faculties. We enjoy it when our intellects are stretched and challenged: it’s the same part of us that revels in a great musical performance that is awakened by an architectural space that recognizes the human condition and works to incorporate and engage the individual.

As you know, I was first introduced to Music & Literature via Issue 2 (Krasznahorkai / Tarr / Neumann) when a friend of mine brought my attention to it. I was so excited to see both László Krasznahorkai and Béla Tarr as the focal points of a journal, as I’m working through these two figures in both my creative and critical work. What brought you to focus on these three figures for this issue? I’m especially curious since your website states your dedication to publishing work “on and by under-represented artists.” Do you feel these three are still “under-represented” as artists today?

As I suggest above, even the books that dominate chatter in the literary realm receive such little quality critical attention, much less resonate out into the broader culture. Despite some modest attention recently, I do think that Krasznahorkai and Tarr remain very much under-represented. Even if their names are recognized, their art remains largely obscured. This can be said, I believe, of all the artists we feature in Music & Literature. Micheline Aharonian Marcom, Max Neumann, Vladimír Godár, and Maya Homburger are known by very few, and their art resides in virtual anonymity.