Author Spotlight

Andy Devine vs. Davis Schneiderman

(Adam’s note: The other day I was rummaging around in Andy Devine’s gross apartment trying to stomp on a cockroach when I came across a box of cassettes. “What are these, Andy?” I asked. He was passed out on a crap-ass couch. “Mix tapes,” he grunted, “for old girlfriends.” I doubted that. I played one. It was a conversation with Davis Schneiderman. “What are you doing with this interview with Davis Schneiderman, Andy?” I asked. He rolled over on the couch. “Nothing, because I don’t like his cocky last comments.” So I took the tape home with me, transcribed it, and I present it to you now. It’s great. Andy really contextualized and problematizes Schneiderman’s new novel, Blank. Who better than the author of Words to ask questions in a way that points to how much content exists within a book that has no words. Roxane wrote about the book here, should you want more.)

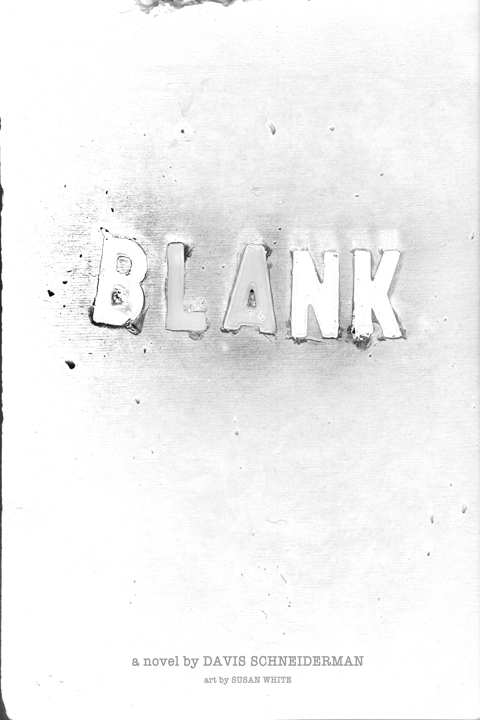

Davis Schneiderman is a multimedia artist and writer and the author or editor of eight print and audio works, including the novels Drain (TriQuarterly/Northwestern) and Blank: a novel (Jaded Ibis), with audio from Dj Spooky; the co-edited collections Retaking the Universe: Williams S. Burroughs in the Age of Globalization (Pluto) and The Exquisite Corpse: Chance and Collaboration in Surrealism’s Parlor Game (Nebraska). His creative work has appeared in numerous publications including Fiction International, The Chicago Tribune, The Iowa Review, TriQuarterly, and Exquisite Corpse, and he is a contributor to The Nervous Breakdown and Big Other. 2010-11 appearances include the University of Notre Dame, the Ukrainian Embassy in D.C, the Chicago Cultural Center, the University of London Institute in Paris, and The New School, among others. He is Chair of the English Department at Lake Forest College, and also Director of Lake Forest College Press/&NOW Books. He edits The &NOW AWARDS: The Best Innovative Writing.

Andy Devine: How did you decide between BLANK and, say, BLANKS or something entirely different for the title?

Davis Schneiderman: I’ve always been fascinated by the titles of musical works, particularly mid-twentieth century jazz compositions. I think how different a work such as Charles Mingus’ “Orange Was the Color of Her Dress, Then Blue Silk” would be if it were called “Untitled” or “Round Midnight” or “Rocket Number 9 Take Off for the Planet Venus” (Sun Ra). The title of minimalist art works can also function in the same way—coding the text or painting or sculpture in a way that is different than how the title of a non-conceptual work might function. Would The Da Vinci Codes have been the same book? What about Chicken Soup for the Souls? For the most part, probably, except that the latter might have approached self-help from a pantheist perspective.

BLANKS also has the joke connotation: a book with that title is shooting blanks, nothings, sound and fury noisemakers. While some will take BLANK as a joke—there is a similar book called Everything Men Know About Women—the title is not necessarily meant to suggest its own futility.

To get at your question a different way, BLANK has a singularity to it that seems compelling to me, especially since the book takes on, to some extent, the questions of authenticity and authority, etc., regarding our notions of plot and story and text. I like the idea that BLANK—just one entire empty space, which is paradoxically not empty—suggests something isomorphic. In this way, and some readers will disagree, I see BLANK as part of a diptych with my last novel, DRAIN (Northwestern, 2010). In the former, a novel that is not a conceptual work a la BLANK, Lake Michigan empties of water. It’s the year, 2039, and all sorts of people—the disenfranchised, the corporate—fight for symbolic control of the empty space. I consider BLANK as a sequel to DRAIN, and the monosyllabic homology is pleasing to me: that central “A” with two letters on either side.

Devine: I was pleased to see that you don’t use any of the words that shouldn’t be used in fiction, as listed in WORDS, but surprised to see that you didn’t use any of the words that should be used in fiction. I’m wondering, as a ______, what you think of words. Don’t you like them?

Schneiderman: I appreciate the stridency by which WORDS make its recommendations. The best think about your WORDS, and there is much to love in that text, which I taught to great effectiveness in a section of Introduction to Creative Writing at Lake Forest College, is the way that the book seeks to reveal structural situations at work in contemporary writing. You have a series of short pieces that consist of word lists in alphabetical order, some words repeated, to create an a-syntactical structural mood.

The plot then—the alphabetized words on the page—come to represent the story—the absent chronological unfolding of events—in interesting ways.

BLANK, while sharing some of the spirit of WORDS, takes not so much the faux-tyranny of your directive lists as its starting point, but the idea that even when we read a text—let’s say The Da Vinci Code, again, for the sake of argument—we are reading not so much the words on the page, but we are reading what we, as readers, bring to the interpretation of those words.

That’s why Sartre’s Being and Nothingness might rock some graduate student’s world, but it will also seem, to another reader, be little more than a mélange of philosophical gobbledygook. For that reader, Sartre has in fact written a blank book—using words. I mean to suggest that all books are blank to some readers, and so even though BLANK uses interior words in the form of chapter titles, the project is an explicit rendering of a larger structure that informs and inhabits all texts, much as your WORDS also offers.

Devine: Based on most of the chapter titles, the novel appears to be told in third person, but the title of Chapter 18 is “You die” and the title of Chapter 19 is “I die.” Is this a shift in perspective or is the reader supposed to _____ something else from these choices?

Schneiderman: This is still in the third person, or to be more specific using narratological terms, the shift suggests an external narrator, an extra-diegetic consciousness, that is also narrating, in these chapters you mention, from an intra-diegtic perspective. Here, it’s as if the voice of some nineteenth-century novel, say the narrator of The Brothers Karamazov, switches to make itself known in a metafictive manner. Surprise, it’s me, Joe, whose been telling you the story of the four brothers. Of course, whenever that move occurs, we must still posit the existence of another extra-diegetic level, since Joe is not a “real” person writing his book about Alyosha Karamazov. Thus, the text we are reading is written by an entity, not the author mind you, who is then writing the figure of Joe into what has previously seemed to be an otherwise omniscient text. Since Joe is figured, literally, as a person, the reader realizes his omniscience must be limited, and his voice is then not the same as the more-distant narrator that previously managed the world of the text.

In BLANK, I bring in an unnamed entity (“I die”) that raises similar questions about the position of the “narrator” that has constructed the chapter titles, which in themselves offer a complete narrative.

Devine: Why is each chapter the same number of pages – except the last chapter?

Schneiderman: Each copy of BLANK is meant to constitute a perfectly refined objet d’art as a way of addressing the crises of reproductive and reduplicative printing technologies. Consider Tristram Shandy, with its 3,000 editions of Volume 3, in that each offered it’s own distinct marbled page.

Advance orders for BLANK will receive their own individuated stamp, and I just received a box from Susan White, the pyrograph artist, with one page from each advance copy burned, lightly, into a soft brown patina. The page is never puncture or singed. I am in the process of writing a text, or the start of a text, on another page—and so these lucky advance purchasers will receive a copy of BLANK that is, like Shandy, different than all others. The fine-art edition of BLANK, which costs $7500 and contains a flash drive with Dj Spooky’s Bach remix tracks, comes encased in plaster, which can be broken only one time to allow entry to the book. That is also a singularity in the midst of reproduction.

For the commercial edition that lacks these flourishes, the sameness of the chapter lengths suggests the cookie-cutter character of a potential text that might more directly represent the content of a chapter such as “They Meet.” Would that be much different in its spirit than the chapter, “They Fall in Love”? Is one Harlequin romance different from the next? Yes. And no.

So many books say the same things in reality the same ways … why should the mass-produced version of BLANK, despite its gestures toward formal unpacking, be successful in escaping the orbit of the greater publishing world?

Devine: Further concerning the chapter titles, I was wondering why you chose to use chapter titles at all? That is, BLANK didn’t have to be structured to indicate any particular kind of story, as it does with the chapter titles. Questioned another way, what gives you the right to impose so much structure on blankness?

Schneiderman: The human drama of BLANK, so to speak, grows from the morphological nerve sensations of the text. Think Vladimir Propp and the Morphology of the Russian Folktale. There, Propp identifies the common markers of all Russian folk tales, and breaks them into the 31 “functions,” that all of these tales draw from.

One possible way to consider BLANK, as I explained above, is as a text that offers structures highlighting the codes of contemporary publishing. While the “functions” of BLANK’s chapter titles are different than Propp’s, certainly, and different than the codes of say, Twilight, there exists no text free of structures that have nothing do with the primary content.

The bibliographic codes—packaging, author photo, bio, chapter titles, fonts, copyright notice, etc.—are perhaps more constitutive of the reading experience than the content of any novel.

To approach from a slightly different angle, the story of the chapter titles also, resonates with the tracks Dj Spooky’s Bach remixes for BLANK, and the way that 50% of the book’s proceeds benefit the Tanna Center for the Arts on Vanuatu in the Pacific. The story of BLANK is also the story of this island, in so much as it is also the chronology of Bach and the anti-interpretation of the Western Canon as put forth by Harold Bloom.

Devine: Describe the collaboration between text and images. Do the images provide insight into the story or are they blanks within the blanks?

Schneiderman: They are pyrograph frames with sky scenes, burnt by Susan White, and they serve as blanks within blanks within non-blanks. These oases of meaning may suggest directions within the larger narrative, and I don’t want to take away from their potential by declaring the boundaries of their insight.

This word—“insight”—is also problematic for conceptual literature, along with “author,” “genius,” “creation.” Take Vanessa Place’s Statement of Facts, or Kenny Goldsmith’s Day or Kent Johnson’s Day, and you’ll find different approaches to this same question. Insight suggests the shedding of light onto a question. This is a humanist idea, and one which I have become increasingly skeptical toward.

Devine: Where does BLANK fit in with John Cage’s 4’33” or Robert Rhyman’s white paintings or Robert Rausenberg’s white paintings or Ken Sparling’s novel that doesn’t have a title or my “Untitled” or Michael Kimball’s “Now Do You Remember?” or other types of “blank” things or just not being able to remember something?

Schneiderman: If you put all of these things on a shelf, and you lay this shelf out horizontally along an X-axis marred by complex root systems that press against and strangle the firm line of the horizon and so cancel out the collective meaning of the texts under consideration, then BLANK, small and wonderful and a delight unto the lord and the best book of the year and a future New York Times Bestseller, ad nauseum, fits at point -3, or just to he left of the Cage.

Tags: andy devine, Davis Schneiderman

I think this book is totalitarian. A bully. I’m not saying that it is therefore a bad piece of art, but one that is subtly intensely ideological under the guise (or is it?) of being something that is “open”. What it actually does is dominate and push you into a very narrow hallway (and I think we’ve walked down this hallway enough already, as a culture). May or may not be intentional. Maybe it’s a “personal problem.”

Interesting. Why do you think it pushes you into a hallway? Do you think there is a predetermined way to “read” it?

I’m thinking something along the lines of: There’s no way to read it other than to speculate on how to read it.

But that doesn’t really feel like the right way of putting it. I don’t have anything better at the moment, but later on (when I am not at work) I’ll try to.

I felt as if it pushed me into an infinite space, except for the chapter titles.

Also I have never had the physical book in my hands.

Infinite possibility can be paralyzing, infinite possibility really only exists in within the… Geist, I’ll say. I don’t know that something like this can do much but engender one to tread water in a sea of abstraction. The illusion is that it is this totally “open” thing, but the dialogue it engenders is actually very limited by its terms because it only exists within this realm of abstraction. I’m not arguing for a “core” or or a “truth” but rather an Interconnection-With-More… definitely with more actual Experience…

Again, I’m not saying BAD, I’m saying that’s what it makes ME feel, it may even be intentional. Everything defines everything else so this has its place too.

So it forces you into the narrow hallway of purely ideological aesthetic speculation without consequence, perhaps. A lot of people want / like this though, I am guilty… as a relief from actuality, more often than not. I’m not making an ethical judgment, or tying not to, at least.

Yes, it can be paralyzing. It can stop attempts to think deeply, in a certain way. And thanks for the narrow hallway explanation.

Probably this all stems from a personal belief on my part that we should be “over” a lot of things that a lot of very smart people are not “over” yet, and that it is possible to use all we have negated and deconstructed in more constructive way. Which is of course totally paradoxical, but that’s sort of what the movement should be towards, in my estimation, paradoxical relevance? Something like a negative theology that denies AND affirms and is relevant-in-actuality in one movement? I actually believe this is what DF Wallace was after but I don’t know if he got there, like how Nietzsche didn’t really “get there” with his deal… it takes a lot of people and a lot of time to get… anywhere. Too much coffee today.

So this book may be necessary… an object that represents something implied in the rest of the grand scheme. I think it’s just a little late. There may be a little of Chomsky’s “intellectual terrorism” involved that makes it impossible to critique as well. I think his reply to the last question was a possible instance of intellectual terrorism.

Thanks for this transcription, Adam. Certainly adds to the discussion surrounding the novel.

If a thousand monkeys planted a thousand apple seeds each, a typewriter would still look like a birds’ nest to a jellyfish.

vipshopper.us

I think you’re onto something, that the book is “necessary.” However, I think that it’s necessary so long as it’s never actualized. At that point, I think it’s only redundant and unnecessary. Another paradox, if you will. And I strongly agree with the earlier comments about this piece being totalitarian. If the piece is considered “open” (which I’m not sure I buy into) then it is open in a way that is very confining. Perhaps in that way Blank is rather unfair title.

A great competition between them.

I share this article soon.

vipshopper.us

http://shortlinks.co.uk/36yj

[…] Devine (with help from Adam Robinson) interviewed you at HTMLGiant.com in the wake of Roxane Gay’s review of BLANK and Christopher Higgs’ contextualization of BLANK […]