Author Spotlight

A Conversation with Philip Graham

Three of Philip Graham’s early books are newly available in Dzanc/Open Road ebook editions. Graham asked me to write the introduction for one of them, The Art of the Knock, and while I was working on it, I asked him a few questions to satisfy my curiosity about his years working with Donald Barthelme and Grace Paley, his time in Africa, and his thoughts on symmetry and design, which are influenced in part by the poetry of Charles Simic and the plays of William Shakespeare.

Three of Philip Graham’s early books are newly available in Dzanc/Open Road ebook editions. Graham asked me to write the introduction for one of them, The Art of the Knock, and while I was working on it, I asked him a few questions to satisfy my curiosity about his years working with Donald Barthelme and Grace Paley, his time in Africa, and his thoughts on symmetry and design, which are influenced in part by the poetry of Charles Simic and the plays of William Shakespeare.

Kyle Minor: I’ve just finished re-reading The Art of the Knock, the book that first brought you to the attention of many readers. I was struck by its symmetries of design, a thing that seems to have been a preoccupation of yours. So many story collections are simply a grab bag, a greatest-hits-lately. But The Art of the Knock is, first and foremost, a book. The parts are in conversation, and they are arranged like a series of Chinese boxes, or Russian matroyshka dolls, on the one hand, and on the other, they are directional. We begin with digging through toward China, and we land in China. We go through three iterations of the “Art of the Knock” series. And the rest of the stories are nested in two in-between sections that seem mirror images one of the other, or at least they are in conversation. How did you find the form of that book? Did you write your way into it, or did the design arrive first?

Philip Graham: Actually, The Art of the Knock grew out of a combination of the two approaches. I’d just published a first book of prose poems, The Vanishings, and my new work was tending toward the short story form. I’d written the first China piece, the first Art of the Knock story (though at the time I didn’t consider them part of a series, they just were what they were), and a few of the family stories—“Silence,” “Shadows,” and “The Distance.” I was simply working my way into a new book, and didn’t have a definite sense of what it might become.

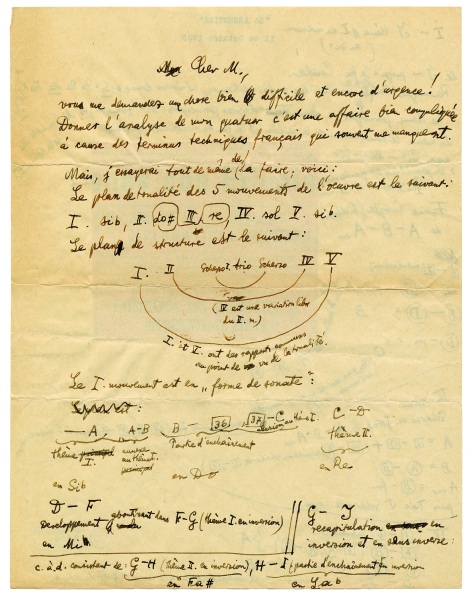

And then something happened. I remember the moment clearly. I was driving home after doing some teaching, a long drive from Richmond, Virginia to Charlottesville, where my wife and I were living, and I was driving against the sunset, squinting at the light, adjusting the visor, and then the structure of the book, just as you so elegantly describe in your question, simply hit, bam, without warning, inside me: the book would have a kind of an arched musical structure, ABCBCBA.

I remember my first reaction to this little revelation was the thought, Wow, nice idea, but I doubt I could pull that off. Somehow, though, I managed to maintain that structure throughout the writing of the individual stories. And I have to confess, the template for such an idea didn’t entirely come out of the ether. In college I’d studied Bartok’s string quartets, and his great fourth and fifth quartets both have an arch structure. Musical material is shared by the first and fifth movements, while the second and fourth movements share their own, and the middle moment in each is its own, strange thing. Together they form an arch structure: ABCBA. Apparently this pattern had burrowed into me.

I was also a huge fan of a book I’d studied in graduate school, Shakespearean Design, by Mark Rose. Shakespeare, apparently, never divided his plays into five acts; that was an editorial decision made by literary critics compiling his work a century after his death. So, Mark Rose asks, how did Shakespeare organize his plays? Turns out, according to Rose, Shakespeare was influenced by late Medieval and early Renaissance diptych and triptych panel paintings, those two- and three-part paintings that often tell or imply a story, through contrast and symmetry. Perhaps the most famous is “The Temptation of Saint Anthony,” by Hieronymus Bosch. While Bosch arranged his painting into a narrative, Shakespeare fit his narratives into the structure of a painting (and Shakespeare created a wide set of variations on this structure).

One quick example: King Lear begins with three scenes. ABA. The first and third are short, private, conniving conversations between two people. Those scenes have nearly the same amount of lines. The middle scene, where Lear punks his own life by dividing his kingdom, is a grand public scene, with many more lines than the two shorter scenes that frame it. Rose goes through play after play, charting the deep symmetries of their structures. Shakespearean Design is an exhilarating book, one that I often assign to my fiction graduate students.

Finally, I was a big fan of Charles Simic’s poetry, particularly his collection Dismantling the Silence, which has a kind of narrative, though not of developing events but developing themes.

An odd collection of literary parents, certainly. I guess my little book had a village of ‘em.

KM: I’m very curious about your literary pedigree. So many of my favorite writers have considered Grace Paley and Donald Barthelme to be their teachers, in the broadest sense of the term—we learn from their stories, we strive toward their intelligence, wit, and freedom. But you actually had both of them as teachers, in actual classrooms, Paley as an undergrad, and Barthelme as a graduate student. What was that like? And what were they like?

PG: Hmmm, more parents.

Grace was my teacher and official mentor—what’s called a “don” at Sarah Lawrence College, for three years when I was an undergraduate. She had a gentle way in the workshop, combining rigor with encouragement. I remember a class discussion of a scene in one of my stories where the narrator throws a cat into a lit fireplace, and I was taking a bit of a beating from the other students—what kind of monster could write such a thing, that poor kitty!—and then Grace quietly entered the fray and used the moment to illustrate the difference between an author and a narrator.

At the time, she was finishing her second collection, Enormous Changes at the Last Minute. I remember her showing me and other of her students the manuscript of “A Conversation with My Father.” She was quite nervous about it and wanted to get all the mirroring levels in it just right. We, of course, had nothing to add. That story is a masterpiece, but how instructive, for a young writer, to think of her uncertainty right up to the point of its publication.

Grace was so down to earth that at first, in my naïve and barely assed-wiped youth, I wondered if she could really be that great of a writer. Her lack of pretension became a steadying force in my life, and the depth of her artistic, moral and political commitments are a standard that I aspire to but can never achieve.

While Grace was mainly a realist writer—though bits of the fantastic could pop up here and there—Donald was a post-modern master. But they both could make prose sing, though to different ends, and in fact they were close friends. They lived across the street from each other in New York, on 11th Street. When I was applying to graduate schools, Grace suggested that I study with Don, she intuited a fit there.

Don was teaching at City College in New York at the time. Now that was a class—Oscar Hijuelos, Ted Mooney, Wesley Brown, Karen Braziller, to name a few. Don would give us little assignments that were meant to help us confront our particular weaknesses as writers. Fairly new to teaching (he was a few years away from his move to the University of Houston), Don was occasionally a little stiff in the classroom, but always a gentleman, and those assignments were spot-on. He was also terrific in conference, a master of fine line editing, bestowing great aphoristic asides.

Don had a sweet formality to him, and an inner discipline that was inspiring. Writing was, after all, work, and you sat down and did it. Funny, he seemed private, but his apartment was often open to his students, something we took advantage of, needy creatures that we were. Don would make drinks, chat a while, and then announce it was time for him to get back to work.

KM: How did Paley and Barthelme influence the trajectory of your work?

PG: They gave me great respect for the inherent truth telling in both the realist and non-realist (the fantastic, surrealism, etc.) traditions. Though it took me a long time to figure it out, my own particular journey as a fiction writer would be to attempt some blend of those two traditions.

And along the way, their advice on the process of writing has been a continuing inspiration. Grace always worked on many stories at once, and she had a batch of folders, each one dedicated to a different story. It was her way of not succumbing to writer’s block—if she got stuck on a particular story, well, on to the next folder and try something there! This strategy made enormous sense to me, and I am always at work on more than one book at a time. I’m plugging away at three at the moment.

Don once encouraged me to write a novel, which was a bit of typical contrarian advice, since at that time I was deep into prose poem-like constructions. I remember replying that I wouldn’t know where to begin, and he said something that has guided me for years. He said that where he began in a novel or a story rarely remained the beginning by the time the work was published. That first bit of inspiration usually found its place near the ending, or in the middle somewhere. Though he didn’t elaborate, I realized that reading a book, from page one to the end, is quite different from the writing of a book. Any book’s chronology is actually made up of disparate puzzle pieces. I’ve found this quite freeing.

KM: You’ve been party to a long literary collaboration with Alma Gottlieb, and, I would assume, a collaboration that is more than literary, since you are married. How does that work?

PG: Alma is a cultural anthropologist, and she and I have lived three times for extended periods with the Beng people, in small villages in the rain forest of Côte d’Ivoire, West Africa, beginning in 1979. While she conducted her research, I worked on my fiction. As you know from your own experiences in Haiti, living in a very different culture can be enormously challenging—it’s a form of on-the-spot translation, and one humbling mistake after another.

The intensity of our experiences included my seeking out a diviner for writer’s block, or our discovering a poisonous snake in our mud house in the middle of the night, or my surviving a bicycle accident that was considered at attack by spirits, but the heart of those years was learning the lives and struggles of villagers who have no voice in the wider world. The richness of it all convinced Alma and me that one day we would have to write a memoir together. This was an odd assumption, since as an academic, she had never written narrative before, and as a fiction writer I’d never given nonfiction a go.

What we finally worked out was a book of alternating first person narratives, working chronologically from our first day in Côte d’Ivoire to our last. Alma would write, say, a five-page section, and then I’d pick up the narrative thread for another section, then Alma, and so on. We’ve written two volumes of a memoir of Africa this way, Parallel Worlds and Braided Worlds.

KM: What have you come to think about literary collaboration, and about authorship, through that process?

PG: It ain’t easy! I would bleat out an annoying sound I dubbed Jargon Alert whenever Alma strayed into the hedging complexities of academic prose. And she made sure I stuck to nonfiction, no fancy embellishments. In a way, we taught each other another way to write, a process that was both extremely difficult and profoundly satisfying, that brought us to another level of marital companionship. Yet through all the writing, sustaining a narrative was paramount. We were attempting a popular, approachable take on the complexities of encountering a radically different culture, and our two memoirs are filled not only with our stories but with many life stories about individual Beng friends and neighbors as they developed over time. In this way, the books have a novelistic feel to them.

The experience of living among the Beng altered me as a writer. I’d been deep into writing stories that had an element of surrealism, and the Beng cultural world seemed at first to be a form of surrealism: witchcraft, spirit possession, and ghosts wandering the village paths were all common sense assumptions. But then as the months passed that local common sense began to feel ordinary to me, I could see how the Beng cosmology worked and fit the lives of the villagers who believed it. Every culture comes up with some pretty weird stuff, and it lives inside the people who share that culture. Everyone’s real inner life can seem fantastic to someone else. I chewed on that for a while, and began writing different sorts of stories. The Art of the Knock, actually, is a record of that stylistic shift.

Finally, I should mention that we receive not a dime from the royalties of the two books—those are dedicated to the Beng people, and after contributing to various projects in Bengland over the years, Alma and I are now in the process of incorporating an NGO that will further help the Beng, who, like their compatriots in Côte d’Ivoire, are still recovering from over a decade of political discontent and then civil war.

KM: When you began to write the dispatches for McSweeney’s, which were eventually collected and expanded upon in The Moon, Come to Earth, did you think you were writing a book?

PG: Oh no, that was supposed to be a side project. I had a year off to work on two books (the novel I am currently completing, and Braided Worlds), and Alma had a year’s leave too, so we decided to live in Lisbon, a favorite city of ours. With Côte d’Ivoire in the throes of extended civil unrest, Alma was looking for a new field site, and she began hanging out with Cape Verdeans in the city. Our daughter Hannah, then eleven, went to Portuguese schools.

Travel, living abroad, sets the synapses on fire. At least it does for me. The present moment is so present, and the ordinary casts off dust that has cloaked its shine. I was at a point in my writing life where I needed that jolt of the new to hit hard, and it did. Those dispatches I sent in to McSweeney’s became necessary breathing for me, and because I was recording the events of my family settling into a life abroad, a kind of narrative, a plot began to emerge in real time, the significance of which was not entirely clear to me until later.

The book may have started out as a portrait of Lisbon, but eventually it became a tale about family, and specifically about my daughter, and her struggles as a child facing another culture. Alma and I were also writing the first drafts Braided Worlds, which, alongside its continued engagement with the Beng people and their lives, also has an emphasis on family. Our last extended stay among the Beng we brought our son Nathaniel along, who was six at the time. So there I was in Lisbon, a transplanted American fiction writer, working on two books of nonfiction that were, in fundamental ways, about my children.

KM: How has your long engagement with other parts of the world – Portugal, Africa – changed the way you’ve thought about literature, writing, all things?

PG: I grew up in an emotionally disruptive family, where truth was routinely papered over by silence and denial. A great deal of my life since those early years has been a form of recovery, and I’ve come to see my fiction and nonfiction writing as complementary. The fiction explores every which way a family can go wrong, or at least slip down a ditch on even a clear and sunny day. And one thread of my three travel memoirs chronicles my continuing attempts, as a husband and a father, to hold a family together.

As for any wider artistic vision, at this point in my life I feel local in a lot of places: the New York area, where I grew up, Côte d’Ivoire, Portugal, and Illinois in the Midwest, where I’ve taught for years and years. Cape Verde, too. So many elsewheres knead and shape who I might be, and that helps, I think, the process of imagining the inner landscapes of my fictional characters.

KM: You’re still actively pursuing a print publishing career, and now Dzanc Books is reprinting some of your earlier work in e-book editions. What do you think about e-books, as a form? Do you see them as simply another delivery technology, or do they offer anything new to the writer who began in print?

PG: I couldn’t be more delighted with the Dzanc Book e-reprints of my early work—what a great work they’re doing, recovering so many books in that series. It’s so satisfying to see my two story collections available once again (thank you again, Kyle, for your poetic introduction in the e-book version of The Art of the Knock), and I even gave my novel, How to Read an Unwritten Language, another revision go-round.

Robert Olen Butler once said to me that e-books will be a writer’s immortality. Once in pixels, always in pixels, and in the future no publisher can keep your work “out-of-print” and cloistered from potential readers. I spend a good deal of time recommending—to friends, students, chance acquaintances—wonderful books that are unfortunately out of print. In the not too distant future that may not be an issue, and better the sale benefits the author and not the used book dealer, however dedicated he or she may be.

Though the grim skull face of piracy also rears its ugly head when it comes to digital, I’ve come to appreciate what e-books offer as a reading experience. Soon after I bought an iPad (spurred by the fact that my son, a software engineer at Apple, had worked on it), I took my first dip in digital waters: the e-book version of Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall. After a few false starts with the page sweep, I quickly adapted, though I missed the heft and texture of a print version.

In those first months I still read a lot of print books, going back and forth between the two formats. Then one evening Alma and I were reading in bed and I was wending my way through the first few pages of the paperback edition of César Aira’s novel Ghosts. Already I felt vaguely irked that the text wasn’t backlit and that I had to strain my eyes to read the nonadjustable smallish print. The novel begins at a construction site, and there was an architectural term I didn’t quite know the meaning of, so I pressed my finger against the page and Alma started laughing at me—I’d forgotten I was reading a paper edition and couldn’t simply touch a word to trick up the definition! That was the moment I realized I was hooked.

For a while there I read almost nothing but e-books, and now I divide my time equally between the two. Each format has pleasures and conveniences the other can’t compete with. And in the end, a wonderful book is just that, a wonderful book.

KM: Could you tell us a little about what you’re working on, now, and what new work we might see from you soon?

PG: As I mentioned earlier, I’m working on three books right now, though two are simmering a bit on the backburner. One of those is a book on the craft of fiction and nonfiction that is shaping up as a kind of autobiography of my reading and writing life. I’ve been writing up sections of this book for a few years now, and posting them on my website (www.philipgraham.net). The other project is a novella inspired by my two stints as a volunteer near Ground Zero in New York, in 2001 and early 2002.

The third project is a novel, Invisible Country, which I’ve been writing, on and off, since the mid-nineties. I’ve been publishing selected chapters from the novel for the past decade or so, and now it has finally found its way to the top of the cue. I’m almost done, I think.

The inspiration goes back to 1993, when Alma and I last lived among the Beng. The Beng ethnic area is pretty isolated, and so when I received word that my father had died back in the States, it was too late to return for the funeral. What to do?

My father had always wanted to travel, though he never did manage to do much of it—that was one small aspect of the family dysfunction. I thought, why not honor my dad through a funeral in the village? So Alma and I went through the various Beng ritual traditions. I write about this funeral (http://www.mcsweeneys.net/articles/my-fathers-african-afterlife) in Braided Worlds, and the demands of truth telling made it one of my toughest challenges. Though the scene comes in the middle of the memoir, it was the very last of my sections that I wrote for the book.

Soon after the funeral, a close friend in the village, Kokora Kouassi, began reporting his dreams to me, dreams in which my father appeared to him from the Beng afterlife. The Beng believe that the dead exist invisibly among the living, so Kouassi’s empathetic dreams were his way, I believe, of bringing my father, who had died so far away, closer to me.

Though I was still writing How to Read an Unwritten Language, I had to put it on pause for a few weeks, since a batch of characters began popping up unbidden in my imagination. They were all ghosts, all Americans, wandering a Midwestern town much like the one I live in, and yet their afterlife was modeled on the Beng concept of the afterlife. Virtually all the characters of the novel came to me in those few weeks, and I’m been building the novel around them ever since.

One ghost, a former mechanic, hovers at street corners and listens to the engines of the cars idling at the traffic light. If he hears trouble, he floats into the engine block and imagines the best way to repair it. But then he discovers that some drivers are listening to audio books, and he becomes hooked on all the stories that are driving around town. Another ghost is an entomologist who decides, upon her death, to squeeze her invisible body down to ant size, adopt an ant colony and continue her research. How these characters all meet up is what fuels the novel’s narrative.

I should say, finally, that this novel brings together, in a way, the various strains of my writing output, fictional and nonfictional. Yes, this is a novel about a fictional afterlife, and yet for the Beng their concept of the afterlife is, to them, absolutely nonfiction, a real spiritual landscape. It also combines my honoring of the Beng and their cultural world with a decision I made years ago to honor the memory of my father, an attempt to help heal, however posthumously, a deeply problematic relationship.

I’m just a few months away from finishing, so my brain is setting off sparklers right now, with a few Roman Candles thrown in for good measure . . .

The page from Bartók’s notebooks and the story of its (possible) catalysis of – or at least relation to – structure in Graham’s Art of the Knock reminded me of:

–Cloud Atlas

Not sure where Graham got the idea that the divisions of Shakespeare’s plays into five-act architectures “was an editorial decision made by literary critics compiling his works a century after his death” – that book of Rose’s? – , but it’s certainly false.

Here’s a facsimile of the First Folio, published seven years after Shakespeare’s death; e-leaf through it and you’ll see that many, though not all, of the 36 plays in it are divided into five acts. (I typed in page “50”, and was taken to page 32 of the Folio, on which is the labeled beginning of Actus Quartus. Scæna Prima. (‘Act the Fourth. Scene the First.’, or ‘Act 4, Scene 1’, or ‘IV.i.’) of Two Gentlemen of Verona.)

And here’s the beginning of an discussion of Elizabethan play division that asserts strongly that the five-act structure was contemporaneously pretty normal.

To my amateur knowledge, the controversy between continuous-flow printing (and writing) and printing broken into acts has been settled largely in the favor of the latter understanding, namely, that while plays were printed without act breaks, other (and sometimes those same) plays were so divided at roughly the same time, suggesting that the continuous printing was the (convenience-based? cost-effective?) anomaly.

“[A]s an academic, she had never written narrative before, and as a fiction writer I’d never given nonfiction a go.”

It sounds a ideal collaboration: the strengths of each strengthening the other.

It seems to me, though, that as strict or absolute assertions, the two seem unlikely. “Narrative” taken in its colloquial meaning of ‘storytelling’, though there is non-narrative academic work (math, physical science), cultural anthropology is rife with narrative; it seems inescapable to tell the stories of some culture or world – or one’s experience of that culture – except as, well, ‘story’.

And discounting the objection that, say, a paper for a history class is “nonfiction”, it’s a shame that fiction (and poetry) creative-writing students aren’t routinely expected to try writing ‘official’ nonfiction. Were I to design such a major or master’s – I’ve never taken even a class in creative writing, :( – , I’d require a semester of, what, creative nonfiction. What rational poet, short-story writer, or novelist would complain about the pleasures and edification of such an exercise?

‘parently, the controversy is fresher than I’d thought.

I just came across this in Stanley Wells’s Shakespeare & Co. (which I only coincidentally just started reading):

* I think Wells here means the 1596 reconversion of the Blackfriars, which had first been made into a theatre in 1576.

To this assertion of ‘general conception’, I’d say two things: a) That a play is printed without breaks or performed without intermission(s) doesn’t mean that it wasn’t thought-of and written with a more-or-less clear structure. b) That the five-act model emerged from a chaos of competing numbers of acts seems to me much less plausible than that it represents the coalescence of a more-or-less open, more-or-less consensual pattern that was already more-or-less consciously at work.

(I should remind: however rational my point of view is, it’s absolutely that of a dilettante.)