Author Spotlight

An Interview with Sean Thomas Dougherty

I first met Sean Thomas Dougherty at my first AWP conference, Denver 2010. I had been wandering the overwhelming aisles of the Book Fair, wondering what I had gotten myself into, when I found myself at the BOA table. A book called Sasha Sings the Laundry on the Line caught my eye. That mesmerizing title with the Eastern European name, the cover art of colorful dresses and towels hanging between sooty apartment buildings, a wedge of blue sky above – it reminded me of my old neighborhood of Midwood, Brooklyn, and when I picked up the book I read the name. This was a guy whose poems I had long admired, and I hadn’t realized he had a new book out. When paying for Sasha, the BOA rep behind the table asked, “Would you like Sean to sign it?” I told her I needed to get going, but then she pointed behind me: reddish hair under a cool hat, big hooded sweatshirt, pale blue eyes, warm smile: Sean Thomas Dougherty. Signing his book, Sean wanted to know my story right away. He lit up when I told him I was a college dropout. “You’ve got to put that in your author bio,” he said.

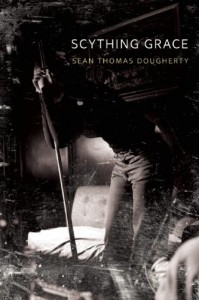

Sean and I have kept in touch since Denver, mostly via email and Facebook. Sean is hands-down my favorite Facebook presence. His barbs at mediocre poetry, his posts of music videos on his “Punk Rock Sundays,” and his constant promotion of indie magazines and presses, as well as of the poets he loves, is something I look forward to daily. When I heard Sean had a new book in the works, I contacted him about doing an interview. That book, Scything Grace, is now out with Etruscan Press. Dougherty’s poems sing of the tough realities of American city life, with a voice influenced by Lorca and Vallejo, Levis and Hull, but a voice truly all his own. He draws close the lives and deaths of those he loves, and sees and hears the stories of the American poor and working class all around him. His poems from the beginning have challenged the division between poetry and prose, and are loyal to nothing if not sound, and great feeling. Poet Dorianne Laux has written that Dougherty is a poet “of grand and memorable vision . . . the gypsy punk heart of American poetry.”

In the following interview, conducted via email over a few days last May, Sean and I discuss Scything Grace, the line versus the sentence, Li-Young Lee, and the duende.

***

Justin Bigos: Your latest book of poems, Scything Grace, shows you continuing to push the formal possibilities of your poetry, as well as hitting what I hear as a more recent note in your work: the voice of an older, more self-aware poet, who carries his ghosts through the streets and witnesses language and song everywhere, as if the world were scripting itself, singing itself daily into existence. Can we start our conversation by looking at this book as the next chapter in your life’s body of work? How have you changed as a poet since Sasha Sings the Laundry on the Line?

Justin Bigos: Your latest book of poems, Scything Grace, shows you continuing to push the formal possibilities of your poetry, as well as hitting what I hear as a more recent note in your work: the voice of an older, more self-aware poet, who carries his ghosts through the streets and witnesses language and song everywhere, as if the world were scripting itself, singing itself daily into existence. Can we start our conversation by looking at this book as the next chapter in your life’s body of work? How have you changed as a poet since Sasha Sings the Laundry on the Line?

Sean Thomas Dougherty: This is a hard question for me because I haven’t really “read” Scything Grace yet. It is an improvisatory collage. So I will answer in an improvisatory collage, which is the way I’ve started to write more and more in the last decade. The way closest to how I think, how I feel.

Back in May 2012 I was walking with my friend the poet Corey Zeller at the park on the west side of Erie, Pennsylvania, where I take our children to run through the last cherry blossoms. Pale petals we are. Sometimes when I walk I will just start talking to Corey poems and he will say, write that shit down. And I say, no one time. The poem is now gone. I’ve been doing this for decades for my friends. I say I am a walking saxophone. I say I am the words hiding all around us. Monk once said he has a hard time not hearing the music, it is everywhere, he wants to reach up and catch it as it passes us by. Flea, the bassist from Red Hot Chili Peppers, says the same thing. Everything has a beat. Think of a billion living things, the smallest insects. Human hearts. The rush of traffic. A swallow’s wings sing the air. I actually “write” very little all year. I write maybe two months and then the rest of the time I live, I collect, I listen, but I say poems all the time. I think part of being a poet is to live the poem, so I spontaneously make poems for the people I care about. I make poetry part of the fabric of us.

In May 2012 I had just finished a grueling grind-out manuscript for BOA of my Selected Poems to appear in 2014. Some of the poems in there I had been crafting for over six years. Corey’s best friend Jeremy, who I had known for years too, had just hung himself. Corey was dealing with his death and trying to write poems in his voice. It was spring. We walked carrying such weight. My love Lisa was very sick. My second daughter had been born in January. My oldest, Amara Rumi, was four. She ran with Corey’s son Malcolm. To live in a city of rust along a lake between nations. Our children are a lake between nations. Corey said now that you have finished your Selected you should write a book the way you speak poems. Just riff them fast. But write them down.

I said, yeah like Sonny Rollins playing with the birds on the Williamsburg Bridge. Legend has it when Rollins felt stuck he spent a year listening and playing with the birds on the bridge. He disappeared into life to find a new sound, a new tone. I needed to find a new tone. To return into the improvisatory language that drove me to poetry thirty years ago. For decades I’ve been pulled into the river. Now I gave myself permission to not swim but drown in it. I was also interested in writing much shorter lyric poems. My love Lisa is very sick and her favorite poems are my shorter lyric poems.

So two very important people in my life pushed me to make this book of short improvised lyrics. Then I expanded the breath to close. It is a Book of Breaths.

I started with a quote from Cavafy. In many ways the entire new book Scything Grace was driven by these lines from Cavafy’s poem “The City” :

“…I see the black ruins of my life, here,

Where I’ve spent so many years, wasted them destroyed them totally.”You won’t find a new county, won’t find another shore.

The city will always pursue you.

I wrote 80 percent of Scything Grace in a sort of old school improvisatory haze fueled by the duende, black coffee, and cigarettes over four weeks in May 2012. After I was done, I hit spell check, told my friends I was sending it out. It was done. I wrote it linearly one poem after another, day after day, sometimes two or three poems per day. I sent it out on a Saturday night in late June, I think, to Four Ways Books, Etruscan Press, and Black Ocean Books. On Monday afternoon Phil Brady of Etruscan called me up ecstatic to accept it.

JB: I’m really interested in how you articulate some of the paradoxes of the poem – at least the kind you write and are drawn to – especially the paradox of the poem as something received yet also made. It is you, Sean Thomas Dougherty, writing these poems—but as a kind of conduit, a witness. In that sense, the writing seems less about arranging sound and experience than transmitting it. If this is true, how do you know when to improvise, when to guide, when to allow your own will in there to have its say?

STD: You can’t teach someone to make metaphors, but you can teach the structure and examine how they are made or why certain images arise from the imagination, the way the French phenomenologist Gaston Bachelard in his profound book The Poetics of Space points to rooms, windows, doors, spaces intimate and grand, the juxtaposition between things, between worlds. But in the end there is an unnamable space to the making, that is the human spirit, soul I dare say, history of language and learning, the imagination made manifest in words. But it is also the body. The body remembers. So while the mind may let go the body becomes an instrument of sight, and very particular for the poet, of sound.

JB: You mention spaces such as “windows, rooms, doors”—spaces that are portals, hinges between other kinds of space, “between worlds.” I notice these images in much of Scything Grace. For example, in the poem “The Literacy of Longing,” these lines: “the doors// that must not close I follow you through// to travel when we weren’t looking// in a waiting room a window// I turn towards the unfolding dark// to tell you everything is opening.” And, as in these lines, the speaker in Scything Grace is often searching for a “you” the speaker “still breathe[s],” a face that is his “last known address.” Most of the poems in this book, if not all of them, read like love poems. Do you consider yourself a love poet, or is that label too simple or outdated? Is duende something necessary to write a love poem?

STD: My friend Joe Weil told me years ago, “you are the only poet I know who only writes love poems.” At least I didn’t know what he meant, I thought he was insulting me, but then I understood. It was true. The world, full of such suffering, the people in it, ice breaking into shards in spring, the swallowed sky, swallows, fields of dried willows where teenagers huff gasoline, the corner lots of city blocks where boys dive to catch like swallows that dive from barren trees, these things I see, these sounds, each a letter in a new alphabet of making, and what they spell is both desire and loss, loss and desire, and often something resembling love. And in poetry too of our dominant historicities are the elegy and the ode, two forms that I have always argued are actually love poems. That the best ones written in English are love poems.

And I am obsessed with these two forms, and have been since I began writing, because for me my poetic enemy is the maudlin poem, the melancholy poem, the quaint poem. Instead I am driven by the poem of excess feeling. Our father and mother Whitman and Dickinson were poets of excess feeling. God how often Dickinson is misread!

My “you”s are often my partner Lisa who is very sick and daily fights against her autoimmune disease, but often too that “you” is I or the reader, or a larger You, or an ambiguous “you” that encompasses all of us, all of us who suffer, all of us who shine. In spaces intimate and large, open and closed. Opaque and translucent.

The human heart is a prism.

To make the poem into a prism.

How to tell what is almost unbearable even for I to listen. How to weave voices and fragments both from my life and the overheard lives of so many others.

To love so fierce even before or after. Whatever is. In these poems I have so much to tell the “you” but much is withheld from the reader. Perhaps this is a darker version of Frank O’Hara’s Personism, where the poem is near a letter. This is the eavesdropped. To tell a story to a “you” where much is already known, to leave the ambiguous space for the reader to enter and add their own life.

This is the Third Way I have been writing towards for decades. Somewhere not near so called Elliptical and not transparent and “real” or simply formal. But somewhere between. The spaces between things. And we are back to windows, to doors where we can only see the hands of the Beloved weaving something, or singing.

I think to write a true love poem, the kind that reflects this notion of love, one needs to embrace the duende, one must write into the flames and have the black sunburn burn into your chest.

Too many love poems are quaint or sweet. Love is not sweet. In the end, we die. Lorca says to create with duende is to acknowledge the awareness of death. All love that is worthy. Jack Gilbert knew this. Frank Stanford knew this. Lynda Hull knew this.

JB: That Lorca claim reminds me of something Li-Young Lee once said in an interview: he said that all poems must have death in them. And he said they must also have “the divine.” You used the word “soul” earlier. Do you believe in divinity? Your poems are often prayer-like, “broken hallelujahs.” Would you call yourself religious?

STD: I never heard that claim from Li-Young Lee but I am not surprised: it is in so many ways reflective of his work. His book The Winged Seed is one of my bibles. It is one of the most undervalued books in recent American literature. People don’t get that book because it is a prism book. It is so beyond any of his books of poems, which by comparison, seem tame despite their lyrical pathos. But when one reads The Winged Seed you get the feeling that to write that book nearly killed Li-Young Lee. The story is he wrote it over and over again over a weekend. He wrote it over days, then discarded it, wrote it over days, then discarded it. Finally it fell from that room inside him, something not whole, but a whole note. Notes. Sentences from him like whole poems:

But here it is night, and anyone awake this late, weighing for himself seeds and forgetfulness, the white grains of his insomnia and the weight of the whole night, must begin to suspect he is of no particular origin, though sit at a window long enough, late enough, and you may hear a secret you’ll tomorrow, parallel to the morning, tell on a wide, white bed, to a woman like a sown ledge of wheat. (55)

Again here we turn to the idea of improvisation and spontaneity and embracing it and one thing we haven’t spoken about the willingness as an artist to discard tons of text when necessary to create more. The poet Michael Burkard once said to me, “Sometimes it feels better to simply write another poem than revise the old one.” Soon after that he gave up intensive revision to embrace the idea of making, the continuity of making, the abandonment of reworking for the improvisation of the New.

This idea of “the Baptism of newly created things,” which is the phrase Lorca uses to speak of the duende, is a near-religious one for me. And a revolutionary one. By making and re-making the world we resist the forces of Capital and the inscription of monetary worth and re-see a world more just and humane. We make not for profit. We make to save lives.

This is the difference between art and commerce.

I have a dream that sound will one day save us all.

JB: Aside from the two prose books you’ve published, your poetry collections contain many prose poems – I’d say half the poems or more. Can you talk more about how the sentence became your preferred music? If so, why write in the line at all?

STD: A sentence is always complete, even when open.

In some ways, every sentence can have the power of a poem, or dare I say, a novel. Look at that sentence from Li-Young Lee. That was one sentence with near a lifetime inside it. I immerse myself in tons of prose and prose poetry by writers such as Gertrude Stein, Rosmarie Waldrop, John Yau, Julio Cortázar, Ishmael Reed, Italo Calvino, Charles Simic, Pierre Reverdy, Stratis Haviaras—in particular Haviaras, and Carole Maso’s novel Ava as if it was the bible, along with the work of the underground Detroit fiction writer Peter Markus. These writers are writers who push syntax to find new noise/sound/meaning in the sentence but at the same time retain a sense of narrative. Oddly, much of my poetry is heavily influenced by experimental fiction that pushes the sentence to open up meaning.

When juxtaposition and metaphor combine, the exploratory opportunity for new meaning-making is limitless.

I am obsessed with how metaphors manifest themselves in sentences much more than where someone breaks their line. I think the first issue is near cosmic and metaphysical, the second is more a craft issue, the way a good chair is made.

What we are interested in, though, is how a tree makes wood. And the psalm hidden inside it.

***

Sean Thomas Dougherty is a self-described “underground/sound.” A border crosser by birth, Dougherty was raised in a politically radical, interracial family. Known for his electrifying performances, he has performed at hundreds of venues, universities, and festivals across North America and Europe, including the Lollapalooza Music Festival, the Detroit Art Festival, the Rochester Symphony Orchestra, the London (UK) Poetry Café, and the BardFest Series in Budapest, Hungary. Dougherty is the author or editor of thirteen books across genre, including the forthcoming All I Ask for Is Longing: Poems 1994-2014 (2014 BOA Editions), and Scything Grace (2013 Etruscan Press). Other books include Sasha Sings the Laundry on the Line (2010 BOA Editions), which was a finalist for Binghamton University Milton Kessler’s literary prize for the best book by a poet over 40; the prose-poem-novel The Blue City (2008 Marick Press/Wayne State University); and Broken Hallelujahs (2007 BOA Editions). He is the recipient of two Pennsylvania Council for the Arts Fellowships in Poetry and a Fulbright Lectureship to the Balkans. After having taught creative writing at Syracuse University, Penn State University, Case Western University, and Cleveland State University, Dougherty currently works at a pool hall. In the summer of 2013 he was poet in residence at the MFA Program at Chatham University.

Justin Bigos received his MFA from Warren Wilson College, and lives in Flagstaff, Arizona, where he recently joined the creative writing faculty at Northern Arizona University. His poems have appeared in magazines including Ploughshares, The Collagist, New England Review, The Gettysburg Review, and iO; interviews and reviews have appeared online in 32 Poems, the American Literary Review, and HTMLGIANT. He is co-editor of Waxwing.

Tags: Justin Bigos, Sean Thomas Dougherty

[…] an interview on his 2013 collection, Scything Grace, visit HTMLGIANT. For more information on his wide range of works, visit his Facebook […]

[…] every day and they become a neurotic mess if they are not.” The point is amplified in a 2013 interview with Justin Bigos: “Too many poets negate the life from the poem. For me the poem is an […]