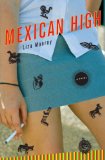

Author Spotlight

Interview with Liza Monroy

LM: I am enormously influenced by place. As an only child with a single mom who moved around all the time, I got to spend a lot of time alone growing up in foreign countries and on weekends and holidays all Mom wanted to do was travel, so that was a huge thing for me, taking in places. High school in Mexico City was the subject I wanted to write about first; ever since I graduated and moved back to the States, I knew that if I succeeded in writing a novel, my first would be “the Mexico City high school project.” It was just such a unique world: bodyguards and drivers waiting outside the school for certain kids, the extreme nature of the city–altitude, pollution, beauty, chaos, history, freedom…the warmth of the culture, the gap between social classes, political assassinations that hit close to home, the chance that something could happen to my mother with the kinds of cases she had to work on…it was overall such an intense experience I couldn’t not write about it.

In this case it was place, this city, that sprung the novel. In my new project place is important, too, but not as important. It’s more about someone’s ability to stay in a place. It’s a story of friendship and family, and has more to do with the absurdity of certain laws regarding marriage and immigration. So the new work is primarily character-driven, but there’s still that international component and cultural commentary that I think will always be important to my writing – I’ve got some ideas for the characters’ adventures in Turkey, Italy, and Los Angeles and the book is still in its formative stages.

LM: I’ve had reactions running the gamut from complete love to total hatred and offense! I meant nothing to be a literal depiction, which is why I went with fiction in the first place rather than a memoir of those years. It’s funny because if everything were a flattering portrait and the characters didn’t have flaws and lapses in judgment, there would be no conflict and no way could it be about teenagers at all. My intent was never to portray the world or characters in a negative light–Mila is far from perfect herself–but rather for Mila to function as a sponge absorbing this world, with all the excitement and danger that goes along with it. The characters are composites of parts of myself and imagination, as well as exaggerated traits of people I’d known here and there, but no character is an exact replica of anyone I knew. When Mila leaves Mexico she says she’s going “from one simulacrum of my life to another” – which I intended as a wink to the Mexico City in the book being a manipulated, fictional version of an actual place, the way Mila feels her life is a series of fictions as dictated by her mother’s moves–that she herself can never feel quite real or complete because she lacks roots, pieces of identity, and a place to genuinely feel at home.

LM: It was a little bit crazy and I’m not sure that I could ever repeat the process by which I wrote Mexican High again. I wrote the book in very long bursts, often 20 or 25 pages in a sitting. I felt like I’d been storing up so long to write it I felt a sense of urgency, and I was also trying to see if I could write a novel. At that point it was about seeing how much I could develop, and simply passing the 100, 200, 300-page mark was new to me and completely exciting. I imposed rules–looking back, they were ridiculous rules–where I’d do silly things like drink a large iced coffee and not allow a bathroom break until I hit my 20-page quota for that day. Needless to say, I did a whole lot of rewriting, slowly and more humanely.

CL: Oi! I can’t imagine going weeks without working on a big project. It might evaporate when I’m not looking. I know you’re teaching and taking classes at Columbia during the school year but how are you enjoying a summer of lessened commitments? Do you feel that it’s easier to write when it’s your only obligation or when you’re under a certain amount of constraint?

LM: I’m torn on that question, actually. I tend to think, “as soon as I get everything else off my plate–teaching, freelance gigs, taking workshops–then I will have unencumbered time to write and be as productive as I was during the composition of Mexican High.” It has never once worked out that way. This summer, for example, I thought once the semester ended I would be in the same cafe every morning, executing my routine, and finishing a certain memoir. What happened instead was I realized the memoir was one long character study for a second novel, and began outlining the novel. Then I took on a freelance assignment, profiling Jonathan Lethem for Poets & Writers, so I went up to Maine to do that. Then I took a vacation in Canada. Now I’m writing the profile and also in the early stages of a deal to write a series of YA books as a collaboration, so I’m learning that lesson of “life is what happens when you’re making other plans.” I think constraint is good. I also hope that one day writing will be my only obligation.

I left a lot open-ended and up to chance. Mila’s search for her Mexican politician father was a subplot that’s completely an invention, and I had no idea at the outset if or how she was going to find him. Even what I find to be the strangest coincidence in the book—a breakthrough in the mystery which happens because of a pair of earrings—was a coincidental moment in the writing. It just came out that way. Not planning too much beforehand allowed me to have a lot of fun and spontaneity in Mexican High, but for my new novel I’m deep into an outlining stage. It’s interesting to feel the beginnings of how different books require variations in approach.

CL: Your next book is a memoir though, about a story that I absolutely love. Can you give us your schpeil on that?

LM: Surprise! The memoir and the novel are one.

There’s going to be a lot about what defines love, marriage, and family, and it will be an international romp with ticking clocks and many twists and turns.

I decided on novel instead of memoir because over the past couple of years I learned how much I love freedom, and I would want readers to read my books without scrutinizing what I might have exaggerated or if I am not being self-deprecatingly funny in tone. I’d rather they seek truth in my novel than fakeness in my memoir, or better yet, just get absorbed by the story. A character in a novel can go anywhere. And now that it’s third-person, I can go inside Emir’s head, too, without causing the reader to question how I could know what he’s thinking. For the first time in a long time I am refreshed and ecstatic about writing this. I knew I could never give the story up, I had to pursue it, but the right form just turned out not to be in the nearer realm of past vs. present tense, or short chapters vs. long, or chronological vs. looping through time. It was something entirely other than I initially thought.

Tags: liza monroy, mexican high

[…] Catherine Lacey recently interviewed me for literary blog HTMLgiant. We talked about approaches to writing a first novel, why fiction trumped memoir, and what happens when people think your novel’s characters are them. I divulged what happened to my second book, and another no-longer-secret thing related to my last post. Check it out here. […]