Author Spotlight

NO PUPPET IS DUMBER THAN ITS PUPPETEER: Raymond McDaniel interviewed by Jennifer L. Knox

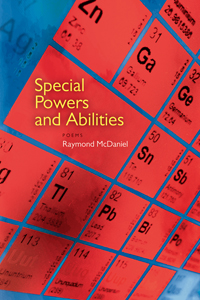

Jennifer L. Knox interviews Raymond McDaniel regarding (among other things) his new book, Special Powers and Abilities, A 100 Page Super Spectacular! Published by Coffee House Press, January 2013

JLK:

1) Why does the robot in your book seem to be the oldest speaker?

2) Are robots in the future older than human beings who are the same age?

3) What is our future society’s relationship to loss? How do we regard it?

4) The image of a puppeteer arguing with a puppet came to my mind as I was reading. The puppet was dressed in gold lamé. Does this make sense to you? If yes, who wins the argument?

RMcD: Ha! Do you refer to Brainiac 5? He isn’t a robot. He’s flesh and blood, lime-green skin and a shock of blond hair, a purple jumpsuit and a yellow force-field belt. He would be flattered that you mistake him for a robot (in that you his appreciate his icy machine logic) but also insulted (as if an actual robot could hope to compete with the mega-intelligence of Brainiac 5).

But if he seems older it’s partly because he comes from a long-lived race, and partly because he defines himself by his capacity for reason and thus has the aloof demeanor of one who thinks he knows better and often does. Often, but not always: just because he is surrounded by absurd teenagers doesn’t mean he is immune to his own strain of absurdity. Check the jumpsuit, the crush on a girl a thousand years dead.

So HIS attitude towards loss is more deliberately meditative than that of his chums, because deliberation and meditation are, like, his thing. But the way it puzzles him reflects the paradox of this shiny future, in which we have solved so many problems that the problems we can’t solve defeat our minds in very childlike ways.

As for the puppet: well, you have to put your intelligence somewhere, right? You can’t actually be your intelligence. A puppet is a great metaphor. After all, no puppet is dumber than its puppeteer; it’s the dummy who explains things to the dumb. So yeah, the puppet is just an extrusion of intellect, almost-divorced from the real person who makes it move, who puts thoughts in its head that are too big to be contained. If you were a toy with 23 points of articulated joints and a mind full of unmanageable intelligence, why wouldn’t you wear gold lame? You are already an extravagance, a superfluity. Tart it up.

[TEN YEARS PASS]

JLK: Sorry this is taking me so long, but rereading your response, I know why. I couldn’t figure out where to go from your reply. It was so narrative and complete–it was a closed explanation, and unlike anything I read in the book, in which I see every poem as being a persona poem–even the ones in boxes which seem to be like comparisons lists.

It reminds me of the Talking Heads song, “And She Was,” in which the girl is flying around and feeling her connectedness with the universe and it turns out David Byrne wrote that song about a girl he went to high school with who used to drop acid and lay in the grass by the Yoo-Hoo factory. In your case, these voices in your book–despite their fantasticness–are constantly brushing by the unfantastic: real human isolation, loneliness, sadness, pointlessness, of not measuring up to this superhero future world they live in. And then after your reply, I find out there’s an extensive back story in your head, unless you were just puling my leg.

How important do you think it is for the readers to know that back story? How do you know when to stick to it, versus let go of it and drift into the more universal?

I feel the box poems are also dramatic monologues, but the that need that this “faceless” voice has to create these poems defines the persona–it needs structure to avoid the real human stuff that seeps into the other poems. I mean: but that the persona’s need for “facelessness” defines the persona–it needs structure to avoid the real human stuff that seeps into the other poems.

What’s the back story on the box poem speaker? It’s not Brainiac 5, is it?

RMcD: I guess every poem IS a persona poem, though it must seem like layers and layers of one persona – a single person trying on every mood and register in order to capture something alien. Alien because it’s unnatural to the speaker’s disposition (glee!), alien because it’s devastating to the speaker (woe!), alien because anything the speaker says refers back to the complexity of how dozens of people represented a character more or less once a month for fifty years (geez).

Maybe that’s where the sadness comes from: not just Brainiac 5’s piñata of bad luck and bad judgment, but from the accumulated cost of spending all that time with your younger, jollier, more naive self. And that might be one thing in THIS world, even in a simulacrum of this world, because we can always shrug it off and say eh, it’s a shitty time in a shittier place and I’m better off disillusioned. But when you are a resident of a better place, a bannerman of a better time, those failures become more acute.

Brainiac 5 could be the narrator of the box poems. I didn’t intend him to be, but I didn’t intend anything when I started them. In fact, those poems (and “Sense-Maps of the United Planets”) more clearly reflect the way I process language and data than anything I’ve ever written. Seriously, if you ever want to know what I am thinking, it sounds something like that. A constant associative buzz. I do it with everything. I could write a Jennifer Knox Box Poem this very instant. I think when Chris Fiscbach saw them for the first time he cried a little. Not salty man-tears of joy, either.

Steve Burt was the first person who suggested that Brainiac 5 is the voice of all the poems, even the box ones. It makes sense, and not just because that’s how Steve does (“Brainiac 5 wrote all these poems, right?” “Yes, Steve. Obvs! Ha ha!” Followed by hasty reevaluation of entire book). It makes sense because there’s something unfiltered and fast about them. Here’s what compressed data would look like, sound like, before someone took the time to translate it.

That also likely answers your question about about backstory. How could I possibly expect readers to know this stuff? I mean, Supergirl, yeah, people know who she is, she starred in The Legend of Billie Jean. But The Persuader? Rond Vidar? This is obscure stuff, even for comic book readers, though I want to say that it is nowhere nearly as obscure as the information at the disposal of the true devotees of The Legion of Super-Heroes, whose collective knowledge dwarfs my own, just like that time Mon-El brought a little bit of white dwarf star matter to Brainy’s Multi-Lab, wreaking havoc that almost but but not quite fails to redeem the moment of single greatest scientific illiteracy in a comic book famous for its love of/disregard for science.

I just hope that everyone’s innate capacity to recognize all the features of narrative without knowing the whole of the narrative will see them through. That’s sort of the point: narrative, plot, character, motive – the forms of these things are more compelling than any of their expressions.

In a thousand years people will respond to Brainiac 5 the way they now respond to David Byrne. And Tina Weymouth? Phantom Girl. Totally Phantom Girl.

JLK: It’s cool that you’re applying this very bare-bones associative technique to such a wild landscape. Because in a way, it’s like any association is just something you’re making up anyway–like all associations are products of the imagination. What about that associative process appeals to you as a poet who also has such a keen a narrative sense? The combo’s a little David Bowie-y.

You say that every poem is a persona poem in the sense that it’s “a single person trying on every mood and register in order to capture something alien.” Also Bowie-y. Please discuss, and do you feel like you lose anything in the process?

What is it about thought before it’s had a chance to become thinking that turns you on? It may seem like a stupid question, but I actually don’t get it. It’s like people want to forget how to cook when they put on the apron, and I really don’t see the appeal. I see the appeal of the poems in this book, certainly, but I don’t see the appeal of the process.

Yes, please write a Jennifer Knox box poem right now.

RMcD: I have long aspired to David Bowie’s closet of fantastic suits, but I am a 42 regular and I think he’s a few inches shorter than I am. But for a cruel genetic twist I could be married to Iman.

My narrative sense is not keen. I could not write a remotely successful narrative poem to save David Bowie’s life. But I do have a keen narrative taste: I consume stories with relish and mustard and competitive vigor. So the associative process doesn’t make narrative so much as describe the ad hoc fluidity of the narrative cataloging process.

And I agree that association is imaginative. What you call forgetting, though, I think of as forced uncertainty. Let’s say you want to bake a cake. You won’t want to forget the rules of baking when you slip on that apron because without rules there is no baking – even with the most liberal definition of baking, absent rules there’s just you sitting in a darkened room slowly extruding a tube of damp cookie dough into your face-hole. But if you want to cook, if you desire the pleasure and challenge of cooking, you might not consult a recipe or even go shopping first. You might just fling open your cupboards and BOOM. Ha ha, foods! I shall make you into a meal!

Oh God. I am starving. Starving, Knox.

What’s lost? Whoa. Good question. Maybe the sense of satisfaction that derives from having never even considered the possibility that one could even try other moods on. That’s the kind of answer you can only give if you are the kind of person who can give that kind of answer. Science!

JLK: I love the distinction between keen narrative sense versus keen narrative taste, because I see that in your work. I really do. It’s easy to perceive, but very hard to define. It’s as if there all these stories swimming around, but it’s more like a marching band competition—very loose shapes crossing each other, and coming out the other side as a different shape. So you see the effect of the elements on each other, but there’s no arc, per se–kind of like a game show. And I think it’s unusual that, as a writer, you love something (narrative) that you don’t try/care to emulate.

Why don’t you?

RMcD: The marching band comparison warms the heart through whose valves run Slurpee. Do you remember when it became apparent to you that Lindsay Buckingham really was going to force the whole of the USC marching brand (the Spirit of Troy!) through a double album of his own psychopathology? 1979. Kids today have no idea what they missed, which is why they don’t miss it.

Wait, did you ask me a question? What kind of a game show is this, Knox?

I don’t know why I don’t try narrative other than my profound conviction that I would suck at it. Like I said, I have no imagination, and experience proves that the more you mightily you struggle to produce a kind of thing you love, the less you will love it. Why do you want to take my love away?

But maybe a better answer is this: people use narrative, and that use shames them. Everyone knows that the blunt tools of story are inadequate to the finesse that fancy deluxe cognition demands, but you cannot find anyone, anywhere, who goes unstoried, if only to themselves. I love that fact. It’s so base. I want to live in that fact, score it, celebrate it; there’s no time to listen and learn how to play the thing I want to listen to.

Besides, what is Ferro Lad’s mask? A mirror. That compels attention. No one wants to see his actual face, just like no one wants to hear Old Man McDaniel’s Very Excellent Stories. I’ll leave that for people who actually have that special power or ability.

JLK: I double-dog dare you, Raymond: tell me a story. Make it short, and sweet, like my dick.

RMcD: Dane saw the gecko loitering in the windowsill of the son of the strip club owner.

I want it, he said.

Don’t, I said.

JLK: And they lived happily ever after, in space.

*

Raymond McDaniel is from Florida. His books are Murder, Saltwater Empire and Special Powers and Abilities, all from Coffee House Press. He writes, albeit inconstantly, for The Constant Critic, and does not teach poetry at the University of Michigan, where he does teach other stuff.

Jennifer L. Knox is the author of three books of poems, The Mystery of the Hidden Driveway, Drunk by Noon,and A Gringo Like Me, all available from Bloof Books. Her poems have appeared in The New Yorker, American Poetry Review and four times in the Best American Poetry series. She is at work on her first novel.