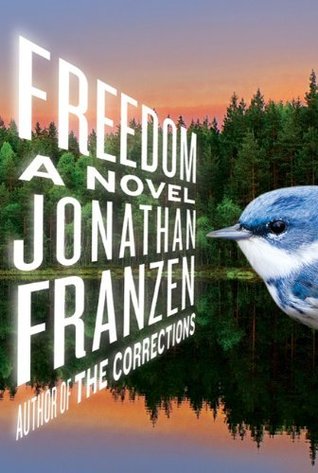

I have qualms about contributing to the current hype around Franzen’s Freedom, the endless pop-noise which ironically is confronted in the book’s lakeside allegory; but I feel compelled to, having been so moved by the book, and apologize for attaching my name to this review.

I have qualms about contributing to the current hype around Franzen’s Freedom, the endless pop-noise which ironically is confronted in the book’s lakeside allegory; but I feel compelled to, having been so moved by the book, and apologize for attaching my name to this review.

Soon after a quick intro written in omniscient third person, the reader encounters a longish part (broken into 3 chapters, labeled as such) written by one of its characters Patty — and yet, this doesn’t feel like “meta-fiction,” or even the show off flourishes of an adroit author; it seems, while not essential, strangely relevant. The reader’s context, for those who know Franzen, is that he is weary of “difficult” fiction for its preoccupation with language and fragmented narrative/consciousness (he wrote a Harper’s article critical of William Gaddis’ infuriating/challenging techniques, yet strangely aligns himself with D.F. Wallace, also an instigator). So one asks, why the difficult-ish structure?

Franzen here stumbles upon a problem: voice. For continuity, Patty’s narration somewhat mimics Franzen’s, but the reader (at least I did), if we are to take Franzen’s conceit literally, is skeptical how a “non-writer” could write so “novelistically.” (James Wood, in How Fiction Works, a well-spirited book despite the didactic title, addresses this issue of authorial voice vs. a character’s — how the latter is an inextricable mouthpiece of the former, what he calls ‘free indirect style.’) Of course, we know this is a necessary, hopefully relevant measure which will augment the overall narrative.

Patty’s offering to the novel becomes essential when, back into Franzen’s third person omniscient account, the physical manuscript “collated” into the novel is actually integrated into the novel’s character’s lives, though, to my relief, not rhetorically like Barthe or Nabokov might have. This is a shocking moment which I cannot get into, for fear of spoilers, an incident which involves the triad of main characters, all of whom are irrevocably changed forever by it.

By this time, as with (sorry for the tiresome comparison) Tolstoy or Dickens, the characters are so fucking developed that the reader almost need not even continue reading, for they can viscerally feel (which is moral knowing) what each character will feel and how they will act, which I understand is the opposite of intellectual, but perhaps fiction’s place, if we have forgotten, is in the heart.

I cried at what happened at the end, because it was so bravely prosaic, almost trivial and boring: ridden with a fate that every human cannot escape, and hence, what every human can relate to, namely, the loss of love. To understand this book, you just need parents, a crush, a relationship, kids of your own, grandparents, neighbors, a job, a house, a life — to have fucked over, to have been fucked over. Franzen’s complexity is not linguistic, but moral. The realism is emitted with such verity, the words seem to breathe on the page. It’s as if he is not there, only the transcribed world at large.

The idea[l][ism] behind the “Great American Novel” is one that is socially cognizant of its time, and Franzen does well to include all the biggies of our contemporary plight: Israel/Palestine; rape, feminism; the Bush Iraqi war; Jews/Gentiles; gentrification; socioeconomic class; wall street fallout and recession; corporate yuppies and artist bohemians; liberals vs. conservatives; racism; the Environment; etc, etc. (he even awkwardly mentions Twitter in the last few pages, like a swansong tweet). I found these parts less interesting than “the story,” and almost annoyed by Franzen’s presumptive “responsibility” in documenting our most recent decade for his classic novel, though to give him the benefit of doubt, he has said to have been so angry at the world that it came out.

By the middle of the novel, the word “freedom” is mentioned sporadically yet consistently, in many different contexts: free-market economic freedom, religious freedom, democratic freedom, marital freedom, sexual freedom, (even cat/bird freedom, which serves as a grand metaphor), and most gravely, the existential freedom to fuck up your life — which will be explained by Patty in her crushing account. Freedom, for Franzen, is a formidable thing, a uniquely American thing which leads to grave consequence when not properly employed. It is, in this book, a bad word.

Franzen’s greatest asset is the moral clarity with which his characters are rendered; a tone often misinterpreted as smug, but I think it’s just the opposite. Franzen is humble enough to not have “style.” His world, however earnest and thoughtfully written, is almost just a journalistic account of ours — how we speak, how we feel, the mistakes we make. His novels are indebted to us, his own voice somewhat orphaned in the background. This is the mark of a great writer.

It’s not “cool” to love a book which will be on Oprah’s book club (incidentally cited in the snippet preceding this post) — a book that does nothing for the avant-garde (if such a thing does or should even exist anymore) — which is what got Franzen into trouble the first time around with Oprah. Freedom, per the incorrigible character Richard Katz (think “dick/cats”), is ultimately an indictment against “cool,” so let’s all not be cool together and read this brilliant, brave, and generous book.

Tags: freedom, jonathan franzen

The strange thing about this book was that although Patty’s ‘voice’ doesn’t differ considerably from the rest of the narrator/ive, it was the one that came alive and stayed in my head for days.

Sorry, I am so sorry for doing this:

“how the ladder is an inextricable mouthpiece of the former”

Should be latter, not ladder.

no worries, fixed, thx.

Jimmy, I will be honest and say that Franzen’s sentences grate on me to the point where I will never give his work a chance. However, I’m curious about this idea, which I’ve seen expressed elsewhere, about “moral clarity” in the book.

I feel like maybe I don’t understand what it means. To me the term “moral clarity” suggests a book written from the perspective that there is, well, clear morality: a perspective that will tell us what is right and wrong without our having to endure much suffering, or that will allow us to suffer in a morally effective way, or, something like that. I tend to prefer books that make me struggle to make sense of the world for myself, though through another’s perspective, and while I believe there are some places where morality could be described as clear, I think they generally make for poor novels.

So I guess I’m asking what this phrase means to you and why you find it appealing.

he’s got a way of describing, arguably ‘judging’ a character, with a quick sentence, that completely makes you understand who that person is; it takes Henry James six pages and Franzen one sentence. also, it’s odd, but he never describes ppl. emotionally, but ‘morally,’ which first conveys resentment, but ultimately empathy. sorry i don’t think i explained myself, it is rather confusing.

Maybe you know this already, but: http://www.newyorker.com/fiction/features/2009/06/08/090608fi_fiction_franzen and http://www.newyorker.com/fiction/features/2010/05/31/100531fi_fiction_franzen

thanks: http://www.openculture.com/2010/08/jonathan_franzens_freedom_the_first_two_chapters.html

No, that makes sense — I guess I just find it unappealing. I don’t think we are all beautiful special mysterious snowflakes, but I don’t like the approach you’re describing either, especially when it’s attended by political labels and buzz words, as it has been in some passages I’ve seen. When a narrator tells me that a character is not a good feminist I get very angry, though it is important to me to be something like a good feminist.

I guess the appeal of it — perceived smugness aside — is that such concise, precise definition of a character can make you feel that you know them, that you are experiencing them and their lives more directly?

not so much political, but using psychological archetypes, like so and so wanted to be this because of that; their impulses are clearly understood. also, with social realism, i think the categorization of people may be necessary to develop intricate character dynamics

Great review, Jimmy. I’m not sure if the judgment element is a good vibe for me, but I guess I’ll have to read it to find out.

I couldn’t understand two consecutive sentences of Mr. Jimmy Chen’s morally clear review, but, from whichever was the very first word, “On”, or “I“, or “Soon”, I declared it a critique de force.

i liked it when one of the characters, on having read patty’s manuscript, commented on how she was a great writer

Jimmy Chen never fails to surprise. I read the book and liked it but not as much as you and disliked some of the thing you liked for different reasons. This review will send me back for a second read.

Craig Nova’s excellent novel The Good Son has a mom-character ‘write’ interspersed chapters, which sections constitute her comment on the story. (She’s an amateur naturalist, and these chapters are field descriptions of flora and fauna.)

Since at least As I Lay Dying, a shuffled deck of (somehow) first-person character perspectives has been a useful technique – a way of bringing what’s almost unavoidable on stage into the describing-theater of a novel. When it’s done well, it’s quite powerful.

(In fact, way earlier than Faulkner (in English): Pamela and Clarissa.)

Good review. Welcome to the un-cool masses.

Hey, Jimmy. It’s cool that you dug the book; since I haven’t read it yet, so I tried to read your review selectively, trying to scan over any of the book’s content and circumventing any kind of spoilers or spoilage. So I may knock over a few cones here. But anyway, I’m curious as to what you mean by saying Franzen has no style, that he’s sort of manifesting a quasi-journalistic sense of what it means to think/speak in American culture today rather than imposing a sensibility. If anything I get sort of the opposite sense–that his judgment infuses and maybe at times dominates his characters…that the commentary is alloyed with the narration to a degree that is what turns off those who find it overbearing and sends others into a tizzy because of that synthesis. To cite an instance from The Corrections: “Although in general Gary applauded the modern trend toward individual self-management of retirement funds and long-distance calling plans and private-schooling options, he was less than thrilled to be given responsibility for his own personal brain chemistry, especially when certain people in his life, notably his father, refused to take any such responsibility….As he entered the darkroom, he estimated that his levels of Neurofactor 3 (i.e. serotonin: a very, very important factor) were posting seven-day or even thirty-day highs…” He accomplishes so much in this snippet, not the least of which is rendering the character while satirizing a large segment of how we think nowadays.

You hit the nail on the head with your James Wood reference–that question of where the author’s voice leaves off and the character’s begins. Wood’s issues with Franzen, his grouping of him with the so-called “hysterical realists” begins, I take it, with his sense that Franzen is imposing too much, that rather than fully inhabiting Gary’s consciousness Franzen is editorializing here about the commodification wrought at a historical moment by some perfect storm of neuroscience, medicine, capitalism, and self-improvement. For Wood, it seems to me that Flaubert would be the ultimate example of someone who evinces a stylelessness, the camera hovering on the street, showing in a frame, the director holding his tongue. At least that’s my recollection of How Fiction Works. Anyway, I like what you’re saying about F. being a kind of a channeling of “our” voices, rather than having an overpowering voice of his own. But I’m skeptical of the conclusion you’ve drawn. And yet you’re so right on the issues, I’m almost certain we’re closer than it seems on this.

Your difficulties are quietly myriad and of great moral and emotional concern.

Your sentence, like many written by Mr. William Gaddis, is pointlessly complex, but, from the very first capital letter, I declared it a sentence de force.

A la Shamela, maybe someone needs to write the book Schmreedom.

From the very margin to the left of that last post, you declared it a pet de force.

Jimmy,

I’ve been against Franzen for a long time, but this review makes me want to give him another shot. Feel responsible. Also, that Harold Bloom comb gag was tops.

It would be ‘Screedom,’ methinks.

yeah that’s better

good one

Breedom: the life, laughter, love of an American family gritty enough to be discontented and self-destructive in the teeth of practically uncontested material comfort and luxury.

I just got this from the library today. Nice… am soon to start reading.

so yeah, i finished it, and i cried too, jimmy. i actually cried, jimmy. i cried. and i only read it because you recommended it in this post. so, um, thanks.