The Necessity of Certain Behaviors

The Necessity of Certain Behaviors

by Shannon Cain

University of Pittsburgh Press, 2011

160 pages / $24.95 Buy from Amazon

Stories in Shannon Cain’s The Necessity of Certain Behaviors pair exhibitionist events and their three-ring tableaus with characters who typify “marginal,” yet who nonetheless surprisingly assert not only their outsider status, often in correlation with their sexualities, but also their complexities—a young lesbian ventures to the set of The Price is Right to meet her father, Bob Barker, only to find not parental but sexual identities challenged; a mayor’s wife endures the scandalizing of her sexuality after she is caught masturbating in the YMCA’s shower room, only to find that her new relegation to sexual deviant has allowed her singular insight into victims of the myriad sexual minefields in her community—the cumulative effect of these stories also achieves a reversal: common notions of taboo or freakishness gain warmth and humanity, while the normative culture unveils its crippling deformities. Cultural critique couldn’t have a more compelling and sophisticated face. In an era often favoring equivocation as a substitute for vision, this collection is clear: take a stand, make it compassionate. Others agree, of interest to note: American Literary Review, American Short Fiction, Colorado Review, Massachusetts Review, Southwards, Tin House, The O. Henry and Pushcart Prizes, the National Endowment for the Arts, and The Drue Heinz Literature Prize.

***

LS: By way of a more wide-ranging introduction to you and to the body of your work, tell us of your current effort, Tucson, The Novel: An Experiment in Literature and Civil Discourse, and what motivated it. A quiet little project, is it?

SC: Tucson has been my hometown for more than thirty years, so when it came time to write a novel—for no better reason than one must write a novel, right?—it made sense to set the story here. Tucson is a microcosm of the American West: overdeveloped, thirsty, beautiful, harsh, wild, heartbreaking. What else does one do but write about one’s home?

The performance aspect of the project was born of a weird volatile mix of my dogged insistence on using literature to change the world and the Year Four, Draft Nine novel doldrums. I knew—and continue to know—that this is an important project for me, but my energy for it was flagging and my narcissistic desire for recognition and/or need to be heard wasn’t being satisfied. A more generous way to describe this might be that I felt an overwhelming need to start making social change on some level, even though the damn manuscript wasn’t done yet.

And I was a political wife. My partner (we’re divorced now) was an elected official during the time of the Tea Party’s ascendance and the resulting nastiness and incivility in the public sphere. I was just blown away by all that anger and refusal to listen; by the need to shout down democratically elected representatives. What had happened to civil discourse, anyhow?

So I started reading the novel as oral testimony at the Tucson City Council meetings each Tuesday. There’s a part of the agenda, Call to the Audience, in which any member of the public is allowed to speak for three minutes on any subject whatsoever. So I sort of hijacked the podium and am using it for art. In addition to reading about 500 words from the manuscript each week, I allot thirty precious seconds toward reflection on the ways in which public discourse unfolds in that room.

About nine months into the project, the Safeway tragedy happened, which was of course the result of Arizona’s shameful neglect of mental health services, its cowboy-era devotion to unfettered gun ownership, and its amused tolerance—bordering on celebration—of public incivility. The shootings gave the project a new urgency. I’ve been at it for almost two years now, and I’m about one-third of the way through the novel. It’s a story about land development and politics (and sex, of course), with the culminating scene taking place in the council chambers. So my choice of venue does have a certain logic to it. Still, each week I’m met by confused silence from the general public. The mayor and councilmembers are used to me by now. One of the councilmembers made me her Artist in Residence, and the Arizona Commission on the Arts selected the project as one of five statewide for a grant last year. I’ve tried not to allow these gestures of approval from The Man to take the wind out of my activist sails.

The Necessity of Certain Behaviors is sexy in every way: mature, uninhibited, susceptible. Does it make you feel sexy?

Hell yeah! Isn’t that the reason everybody writes? To feel sexy?

So I meant that question as a playful ingress, but I once attended a talk with a famously gay author, and though the novel under discussion did not address the topic overtly, during the Q&A, one affable teenager asked (what seemed to me) rather delicate questions about the writer’s sexuality and life as a homosexual, in an attempt, I’m sure, to access not only the activism behind the work, but the person deeply connected to the activism. And it obviously struck me then, as it strikes me when I read you describe yourself as a steward of culture “to bring about social justice,” and you say, “If there’s any genre or tradition working within my stories, it’s political fiction,” and that, “Every week, I need to reaffirm my commitment to literature as a tool for social change,” how it must feel to be a poster child in some ways, especially when one of those ways is, by necessity, intensely private, and when it exists in a culture often promoting the embodiments of its overdevelopment, as in the case of sexuality (so many celebrities come to mind). Another interviewer asked you, “Is there anything you’d like to ask someone who’s read your collection, anything at all?” And you answered, “Did I go too far?” I’m curious to learn, from a successful writer whose thematic concerns have powerful political resonance, more about how you view the connection or reconciliation between promoting the vision that makes politically relevant creative work possible, and emphasizing what complicates direct message, including artistic vulnerability, whether in the creative process or in promotion and discussion of the work… and, I suppose, for the sake of politico-writers like me, and for the thinly-veiled autobiographers, and for every writer at that, how you protect a personal sense of intimacy.

Probably I was born into the wrong culture. In America we’re confused about the relationship of sex to intimacy. We tend to think that if you crawl into the sack with someone, bingo: you’ve got intimacy. This is silly, of course. All you’ve got is the interaction of body parts. Why is jerking someone off more intimate than gazing into his eyes? Why are we so shamed by own healthy, biological desires? Why can’t we see that so often we use sex to hide from intimacy? There are a million good answers to these questions, and they nearly always end in the political. We share 98 percent of our DNA with the bonobo, those marvelously horny little apes who use sex to resolve conflict, express joy, communicate. Humans are sexual beings, and sex is good. But we’ve come to accept that politics/society/religion should have a place in our sex lives, so it’s no wonder we’re confused.

Frank Conroy of Iowa once told a group of us fledgling writers that he saw no reason to write about “the plumbing.” We must write about love, he said, but we don’t need to write about all those body parts. I don’t fully agree with this—I think a lot of great stuff can be discovered in the miraculous, humiliating and confounding physicality of the sex act—but still, his point resonates with me. So when I ask, “Did I go too far?” that’s a reflection of my writerly worry about sex crossing the line into gratuitousness.

So I protect a personal sense of intimacy by understanding the difference between sex and love, but also the difference between fiction and reality. Like most writers, autobiography is all over my work, infused, steeped, unavoidable. These stories come from my brain: how could they not be autobiographical on some profound level? But I am me and they are they. I am real and they are not. No, I tell the creepy guy at my book signing: the naked woman on the cover is not me. Go fuck yourself, dude.

Once you had the idea for each story in this first collection, what helped you most in your creation and follow-through?

The active resistance of knowing what comes next. For me, the process of discovery is where the magic lies. Such weird unexpected truths emerge when I try my damndest to not think about where a story is going until it comes out of my fingers.

How would you describe your best or one of your best experiences working with an editor of a literary journal?

Ben George, back when he was the fiction editor at Tin House (he’s now the editor of Ecotone), took a ruthless knife to “Cultivation,” removing a thousand words from the version I submitted. Also he kept insisting on precision of tiny irritating details like time zones and the physical placement of one character in relation to another. I hated him for monkeying with my genius. Naturally the story came out of this process far stronger than how it went in, and naturally the Tin House revision is the one that appears in the book. Working with Ben taught me not only to value the tremendous gift of good editing, but how to be a better editor of others’ work.

What became the salient points of your book production process? What do you wish you’d known earlier about the book publishing world?

Oh, how fabulous. I just discovered a secondary meaning for the word salient: leaping or jumping: a salient animal. When Ed Ochester from the Pitt Press called to inform me that Alice Mattison had selected my manuscript for the Heinz Prize, I was sitting at Ike’s, a downtown Tucson coffeehouse, laboring over some bit of writing. I became unabashedly, publicly salient. Weeping and leaping. It took eight years to write this book. There is no more salient moment in the life of a writer.

As for what I wish I’d known: before I got the call from Pitt, I’d had the great fortune of working for Kore Press, a fierce and scrappy indie publisher with tremendously high standards for both the quality of a piece of literature and the form in which it is housed. Kore (kor-ay) produces the most gorgeous broadsides, chapbooks, audiobooks and trade paperbacks. For four years, I had the privilege and fun of working alongside Lisa Bowden, the publisher and founder, and learned a whole lot about the industry. So I went into my first-book experience very well prepared. I’m no longer a paid Kore employee, but I volunteer as fiction editor and I co-chair the board of directors.

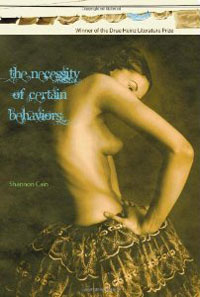

Is there a better cover for any book anywhere than the cover for The Necessity of Certain Behaviors?

No ma’am, there sure isn’t. And there is no writer anywhere who loves her book jacket more than I do.

There’s a marvelous story behind this cover, which confirms the possibility of manifesting desire: ‘way back in 2003 or so, before most of these stories were even written, I was sitting at my desk at Kore Press, daydreaming with Ms. Lisa B. about Some Day. Some Day, I mused, my collection of stories will be published, and Some Day, you’ll design the jacket. And eight years later when the folks at Pitt asked me if I had any ideas for the cover image, I said Nope, but do I have an idea for a designer. And god bless ‘em, they hired Lisa for the job. She knew these stories and their author so well. She understood what they were saying. The photo is by Valerie Galloway, a wildly talented Tucson photographer. When Lisa sent me the cover, I gasped, then wept. Perfect. Perfect.

Writing advice that sucks? Why?

You must write every day. Worse: if you don’t write every day, you’re not a writer. Note that this bit of advice generally comes from white men. My response: screw you and your entitlement. Come over to my house and do my laundry and make my meals and raise my children while I sequester myself in the attic and write the great American novel and then we’ll talk, you prick.

Where can we read more Shannon Cain?

Alas, these stories are the extent of my published fiction. Tragically but typically, I spend more time hustling to make a living than producing creative work. I’m a freelance writing coach and occasional classroom teacher. Hire me to read your short story or novel manuscript and you’ll get plenty of my writing in your margins and in long tough-sweet letters about your work.

***

Shannon Cain blogs at http://www.tucsonthenovel.blogspot.com/. Find her upcoming appearances here.

Lydia Ship‘s stories have appeared in over thirty journals in print and online. She is the new managing editor of The Chattahoochee Review, which is currently accepting entries for its annual Lamar York Prize in Nonfiction, and caretaker of www.magicalrealism.info.

TCR is accepting entries until Jan. 31st.

Tags: interview, Lydia Ship, Shannon Cain, The Necessity of Certain Behaviors

Nice conversation; I definitely want to pick up some of Cain’s work now.

[…] history of publishing, the stories aren’t stealth attempts to double as titillation.” On being asked “if there [was] a better cover for any book anywhere than the cover for The Necessity of Certain […]