Werewolves and White Men: A Conversation with Filmmaker Nick Verdi

Nick Verdi’s films are ragged. Staggeringly no budget but brimming with hideous feeling, each feels like a dry infection. As informed by the work of Jem Cohen and Kelly Reichardt as they are straight-to-video schlock, Verdi’s films function as direct lines into his fascinations: the ease with which communication breaks down; the violence inflicted by (and upon) the young; a creeping sense of apocalypse that no one else seems to notice.

Last year Nick asked me to perform in his latest short film, Angel of the Night, centering around a 35-year-old university employee whose only sincere interactions are when he’s harassing the student body. During a pre-production workshop, Verdi showed me videos of Sam Hyde, John Maus and werewolves for reference. “We’re such strange creatures, aren’t we?” he said. “White men, I mean.”

Nick Verdi: There’s this one movie Moon of the Wolf. It’s such a middle of the road, ABC movie-of-the-week from 1972. It’s a murder mystery set in Louisiana swamp land, and there’s this rich family that owns the town who lives on this giant plantation. And of course, the head of the family—this guy Andrew Rodanthe—ends up being a werewolf. He’s killing people. He kills this girl Ellie—this poor girl. “Why would this poor girl know Andrew Rodanthe—this rich white guy who owns the town?” And it’s because they were lovers and all this shit, you know. But Andrew Rodanthe is like the perfect “unreflective, refusing to reflect, emotionally detached white guy” that has spent all day completely pent up and in hell, and at night it all comes out and he does awful things, the worst fucking things because the more he doesn’t look at himself the worse it is.

And it’d always been, the explanation for the werewolfism in the movie is the sister character— who’s Barbara Rush—talking about Granddaddy. “Granddaddy always had these spells upstairs.” Then years later she realizes it was because he was drinking. And then Andrew is having these same spells. And it’s like, that’s the thing right there. The drinking is the werewolfism. You think about having some blocked memory of seeing your drunk father. The transformation. You know what I mean? It’s the eeriness, the uncanniness of the home being the safe place, but also where the most fucked up things happen. And this sense of: it’s the man with the button down shirt that is the worst thing you know. It’s all these strange, strange things I feel. It’s the main thing I always think about, you know what I mean?

B.R. Yeager: You’ve said that’s one of the things that draws you to John Maus—the way he looks like he’s about to burst out of a tight button down shirt.

NV: Exactly. It’s like I want to see the truth come out in the most violent eruption at whatever expense. The limit of this—this physical body, this form. You come against the limit of your body, and you realize you are not your body. What are you? You know, all this stuff. It’s a tornado inside this person, like what the fuck is going on inside this person, you know?

BRY: You’re talking about wanting the truth to come out, even when (or especially when) the truth is monstrous. Like letting the monstrosity out to be acknowledged. Even though that might be objectively better than holding it in, it’s still terrifying, and maybe confirming things you wish weren’t true.

NV: No, totally—like, the core is a refusal to accept truth. The more you refuse it, the worse it comes back.

BRY: Right.

NV: So it’s always like the refusal to actually self-reflect on whatever—on what you are, on who you are and those things. On things you feel and things you think, you know? Where it’s like you simply have an inability or refusal to self-reflect, or deal for whatever reason.

This topic [werewolves]—this sounds like we’re talking about white men. You know what I mean? This sounds very much like we’re talking about white men right now—the refusal to accept truth, the refusal to accept the truth in yourself. The refusal to accept.

BRY: Which only makes you more monstrous. By hiding it. Because you think that hiding your monstrous aspects will keep you from being a monster. When it’s the opposite. If you don’t figure out how to self-reflect and acknowledge the shitty parts inside you, like address that stuff, the monstrous stuff just bursts out.

NV: Right. Right. Yeah. The other attributes between werewolves and white men is this sense of … you know the Universal The Wolf Man, the Lawrence Talbot character? It’s this shameful, tortured existence. You know what I mean? Like hiding his crying all the time. And that kind of weird sense of faking it through the day but you’re nothing inside. You know? You’re absolutely nothing. And then at night that nothing completely overcomes you. In a simple sense it’s like when someone goes home and gets hammered, and the only way they get any sense of release is through getting hammered and being the worst, as opposed to having some sort of cathartic love of yourself, like selflove being the impossible thing for guys to do. It’s like you’re pretending forever that you’re still doing the 14-year-old dude thing where it’s like “whatever,” when you really have to let that go.

So really I think that tension comes from the refusal of reality, and reality continuously hitting you in the face. And with the werewolf, the tension gets to the point that the fight back is just an absolute nightmare and you succumb to it.

Watch Nick Verdi’s films on Vimeo

Angel of the Night will be released in late September on nobudge.com

August 26th, 2020 / 12:53 pm

plzplztalk2me: Abby Norman

Welcome back to plzplztalk2me, an occasional series in which I talk to folks who want to talk to me! This time around, I talked to Abby Norman.

Abby Norman is the author of ASK ME ABOUT MY UTERUS: My Quest To Make Doctors Believe In Women’s Pain, out from Nation Books in March 2018. Abby and I talked post-election, when we were miserable but still in shock. The interview is short, mainly because I’m a bad interviewer and spaced out our email correspondence over the course of several months. Abby discussed the X-Files, ballroom dancing, and surviving.

***

Abby Norman: It has been the STRANGEST of times. I might be a little FRANTIC AND MELANCHOLY. In general, but today specifically because of the Senate vote.

But like fuck me, right!?

p.e. garcia: Frantic and melancholic is the current state of the nation, I think. Things seem to get worse each day. What’s helping you survive?

Norman: Yeah, it’s a strange time. . .I’m not sure I feel like I am surviving. The last few weeks I’ve found it progressively harder to work in every sense. I should consider myself lucky, I have a manuscript due to the publisher in one month, and therefore there’s always at least a small chunk of my day that MUST be devoted to that and nothing else (i.e. news twitter). For me, there’s always the physical factor because I’m ill, and that I’m used to. I’m not used to being, like, spiritually exhausted. I’m used to wanting to work and finding it challenging because of illness. I’m not used to the feeling of just. . .not wanting to do it in the first place. I don’t know if it’s coming from a place of futility, or exhaustion, or both.

So, I find myself taking my dog for longer walks. Which is probably good for both of us. I live on the Maine coast so we can spend a lot of quiet time in nature which I’ve found particularly helpful. I’ve found myself harkening back to what made me happy as a kid, too: new books that aren’t work related, watching The X-Files before bed, dance lessons. I do ballroom and had gotten to the point over the last few months where I really couldn’t afford it anymore. After the New Year I finally said, you know, fuck it. I’ll find the money. Because I can’t give this up. It’s literally the only non-work related thing I have. It’s physically good for me. And it’s fun. And I’m good at it. It’s not something I show up at and fail at, which is probably a good confidence boost. It’s not like waking up and getting on the internet and having people call me a feminist slut and telling me to kill myself before 9 AM, you know?

garcia: Would you like to talk about your illness? I don’t want to push you to reveal anything you may be uncomfortable sharing.

I understand that feeling of futility and spiritual exhaustion quite well, I think. Lately, I think I’ve become more fatalistic. I think to myself: we will survive, because we must, or we will die, because we will. It’s made me feel like I have less to lose, and thus I feel more open about how I’m feeling and what changes I want in this dumb world. I’m not sure if that attitude is exactly survival, but it’s something.

I’m glad to hear, though, that you have small pockets of self-care. It’s strange what a radical act self-care has become. What books are you reading? What made you interested in ballroom? Where are you in the X-Files (like what season)?

I think there’s been such a strange attitude lately–mostly of people in positions of privilege–of being consolatory toward folks who would literally tell you to kill yourself. But fuck those people. Fuck anyone who would say such vile things to you. You’re better than them, infinitely, and you can take some satisfaction in knowing that their pathetic lives will be spent rotting neck-deep in the viscous garbage that is their own opinions. I would like to place those people on a bicycle, push the bicycle into a lake, and then hurl the lake into an active volcano. I don’t like them.

That’s probably little comfort, of course, but I do hope at the very least you know that you have a supporter in me, and that I will personally challenge anyone who is mean to you to a fist fight.

Norman: Well, I’ve practically built my career on being transparent about my myriad health problems, which were initially of repro nature. I was diagnosed (rather: fought to have the diagnosis I determined confirmed by doctors who thought I was hysteric) with endometriosis several years ago. That’s the subject of my book. Over the last year or so, after struggling with it for about six years, I’d finally started to feel as though I had a handle on it. Then I got shingles, which really fucked me up for a few months. After that, in the spring of this last year, I started having trouble thinking/speaking. My left side went numb. I was terrified I’d had a stroke, which can sometimes happen after you’ve had shingles. Long story short, 9 months worth of testing, and the doctors I’ve seen think its MS. I have some shit going on with my spine that looks freaky as hell, but of course no one has taken the time to explain it other than to call it demyelination. Naturally, being a writer with a proclivity for investigating things at 2 AM, I’ve been spending a lot of time in the Annals of Radiology trying to disprove their theory, but also not liking the looks of the alternatives.

How this shakes out in my day to day life is that I’m very tired and in a lot of pain most days. While the numbness resolved over the course of a few months and is now intermittent rather than constant, I’ve still struggled with certain neurological quirks that’s really given me a crisis of self. I’ve always heavily identified with my intellect, particularly as it pertains to my ability to write and speak. Having that be so imminently threatened has depressed me beyond measure. Imagining that I will soon likely lose my insurance, and no longer be able to experiment with medications that have given my glimpses of normalcy and relief, is beyond depressing. It’s put some of that fatalism in me, too.

But, so too has it put a fearlessness in me. I haven’t got anything to lose except everything. My quality of life, first and foremost. The course of the disease is unpredictable and there’s no way to know, for sure, what particular iteration of it I’ll have or not have. I’ve been told by one specialist that I likely won’t know anything about its progression for at least ten years, because it’s all assessed retrospectively. So, I figure I can’t count on anything. But y’know, no one can really. I guess I just have a more deliberate framework of uncertainty in which to operate.

Self care has always been somewhat radical for me, I think, because it often is for women. I’ve always felt guilty about it. Now it’s just more en vogue to feel guilty about it. As sick as I am, I still feel guilty about even doing things that are arguably quite necessary to my well-being, to my ability to function day in and day out. I often think I’m making things worse by trying to “hold out” and “grin and bear it” as long as possible. I think prevention and proactivity has been cross-wired with indulgence somehow.

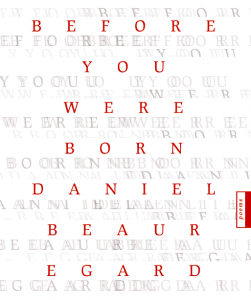

Daniel Beauregard Release Day Interview Party!

Today, my new press, 421 Atlanta, releases Daniel Beauregard’s debut chapbook, Before You Were Born. First things first: you can order it here, or here if you want to get a great deal on both it and Publishing Genius’s newest chapbook release, The Kids I Teach by Andrew Weatherhead and Mallory Whitten. Speaking of Publishing Genius, I thought I’d take a page from PGP man (& BYWB designer) Adam Robinson’s playbook and post a quick but savory Q&A with my author so that HTMLGiant readers can get to know him a little better! It was really interesting to think about Daniel’s poetry as an interviewer instead of as a publisher, and I was very excited to see his thoughtful and candid answers to my questions. And here they are!

Today, my new press, 421 Atlanta, releases Daniel Beauregard’s debut chapbook, Before You Were Born. First things first: you can order it here, or here if you want to get a great deal on both it and Publishing Genius’s newest chapbook release, The Kids I Teach by Andrew Weatherhead and Mallory Whitten. Speaking of Publishing Genius, I thought I’d take a page from PGP man (& BYWB designer) Adam Robinson’s playbook and post a quick but savory Q&A with my author so that HTMLGiant readers can get to know him a little better! It was really interesting to think about Daniel’s poetry as an interviewer instead of as a publisher, and I was very excited to see his thoughtful and candid answers to my questions. And here they are!

How did dreams, objects, and found texts interplay with your process in writing the poems in your new chapbook?

Dreams played a very large role in writing the poems found in “Before You Were Born.” In a way I feel many of the poems were dictated to me through my subconscious—at times I woke in the middle of the night after a dream and the dream became the poem. Other times, things came more sporadically, a line at a time. When I added the lines together they made sense. Or they didn’t. I have a dry erase board next to my bed and if something comes in those hours between waking and dreaming that is important to me, I straggle out of bed and write it down usually without turning on the light. Then I go back to bed or, if the lines keep coming, I’ll turn the light on. Objects played a large role in writing the poems as well. I was obsessed with the way things can be continuously broken down then built into something new. Like an atom bomb or a pulsar. I didn’t rely on found text in these poems as much as I have in my more recent work. However, there are a lot of bits and pieces I’ve picked up along the way that have wedged their way into the poems—conversations, arguments, emails.

And how about The Simpsons?

The Simpsons is always somewhere inside me D’oh. There aren’t many references to the show in “Before You Were Born” but I did steal a line from Superintendent Chalmers. It’s from a scene when Chalmers and Principal Skinner are walking in the parking lot and Chalmers shows Skinner his new car. Skinner says: “It gets me to from A to B—and on weekends, point C.” I do have several other poems that reference the show though.

There’s something about the poems in Before You Were Born that seems, not personal exactly, but private. How do you think about audience and the reader?

There is something that’s a little private in those poems because, in a way, it’s asking the reader to take a step into my mind—to see the things that I obsess over; the things I rant about. Tiny particles. Dust being bits of skin. Swamp lights and the souls of dead children. I don’t like to think about the audience and the reader too much. I like the idea of the reader looking into a glass house. You can throw whatever you want at it but the house will stand or melt into something else, all the while a part of me will remain. These poems are an exercise in understanding myself—they are very much selfish.

What are you working on now?

Lately I’ve been interested in how caves can be used as a larger metaphor for language. I haven’t thought too much about it yet but I’ve begun studying caves via various texts and hopefully over the next few months I can visit some caves myself. I’m interested in how life can thrive in the depths of these caves without any sunlight—bacteria, viruses, extremophiles—not exactly sure where it will go but I’ll continue playing with the idea of desiccation, dissolution and creation. I’ve also got another project titled “HELLO MY MEAT” that I finished recently. It’s a series of loose sonnets created from words and phrases found in various anatomy texts, letters from sea, captain’s logs, butcher manuals and sea diaries from the early 1900s.

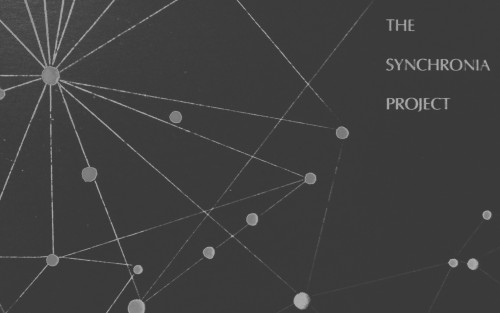

Interview: The Synchronia Project

The Synchronia Project, slated for release next February, is difficult to define. Not exactly a journal, it is a composite, open-ended literary endeavor that will feature work by multiple authors. But it is not a collaboration between the authors; the only collaboration happening is between editors Emily Kiernan and Joe Trinkle , who will be reading the submissions and arranging them into a larger whole. The end goal remains vague, only because the project is still accepting submissions. It is these submissions that will in large part determine Synchronia’s direction, and Kiernan and Trinkle hope to discover a larger narrative—a feeling of synchronicity—across the selected pieces. I had the opportunity to interview these two and learn more about the project.

***

Dan Hoffman: What was the impetus behind The Synchronia Project? Was there a specific literary influence, or did it evolve from a bigger reading of the collective writing you see as editors and writers?

Joe Trinkle: I think it started by us wanting to create something from other people’s work. We’re both writers who read a fair amount of anthologies and literary journals, and we wanted to do something ambitious, something more than just a collection of stories that we like. I think, somewhere in the back of my head, when I’m reading several simultaneously produced journals, online or in print, I notice how much we are writing about the same things or writing in similar voices, and we wanted to play around with that. To see if a pool of submissions would reflect some kind of pattern.

In a larger sense, some of my favorite novels feel like several broken novellas woven together, stories that would not have had nearly as much effect on a reader by themselves, but somehow add to each other, compliment, enhance each other, even if their plots don’t cross paths. I’m thinking Last Exit to Brooklyn, Infinite Jest, and some of the great short story collections of the twentieth century—those kind of books. I actually just read Cloud Atlas, which is a perfect example of what I was thinking about when Emily and I first discussed this project. I wanted to see what it would be like to try to create a fractured novel like that, but with stories from several writers.

Emily Kiernan: It absolutely had a lot to do with the kind of work we like to read. Fracture has been one of the watchwords of literature since the advent of modernism, and. we grew up as readers and writers in a world where that kind of fallen-apart messiness was a dominant form. Most of our models for what it meant to write about the present world, or for what it meant to approximate our experience, inhabited that kind of cut-up space. So of course we are drawn to these broken narratives. One of the first books I remember Joe and I bonding over was Winesburg, Ohio, which had that distinctly modern novel-in-stories form. It is a flat-out rejection of cohesion. Given this history, I think it is natural that we wanted to extend that form outwards, from the book itself to the magazine or the collection.

One thing that I think is remarkable about The Synchronia Project, though–which actually works against this tradition–is that we’re not fracturing something whole, but rather trying to fit these broken pieces together. Binding up the wounds (a little fragment of language that knocks about in my head).

DH: It seems to me that the closest antecedent to The Synchronia Project actually belongs to the realm of cinema, and not of literature, because even if a single literary text unifies multiple narratives it is still, finally, only written by one author; whereas arguably in cinema there is often no single “author” of the film. How much, if at all, was cinema an inspiration for this project?

JT: I watch an embarrassingly low number of films, so my immediate response would be not much. But I’d argue that even though a book usually has only one author, it often times has many editors; it often goes through the finely cut die of a workshop or an MFA program, and the ideas that are infused into the text partly come from reading the work of others. The idea of “one author” is true, but there are a lot of hands on the text, both directly and indirectly.

EK: I also can’t claim any substantial film knowledge, beyond having watched a few more of them than Joe, so any cinema influence on the project would be indirect. As for the one-author element, there actually is a lot of collaborative writing out there, though I suppose it’s more common in poetry than in fiction. (Can I advertise? I’d like to advertise. A few good friends of mine recently started Bon Aire Projects, which publishes exclusively collaborative work.) Jack Kerouac and William S. Burroughs wrote a novel together called And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks. Supposedly the name came from a news report about a fire at a circus—a fact that haunts me. The poor hippos.

DH: On that note, is there any connection between your ideas on authorship (post-Barthes, post-deconstructionism, etc. etc.) and the spirit of The Synchronia Project? Because it seems to me that such an endeavor must in part emerge from a distinctly contemporary conception of what it means to read and interpret texts. Would you say that, in a sense, this is as much about your interpretation of the submissions as their intrinsic qualities?

EK: I don’t think we are out to make any particular comment on authorship–there still exists more than one valid way to own or not own your work–though I suppose we are exploring one of the little rooms that Barthes et al opened up. We’re mostly a bit over-enthusiastic and a bit over-confident and want really badly to be in on the good stuff we see happening all around us in the writing world, so we manufactured this bribe of publication to get our favorite writers to let us futz with their work. We are, in a sense, asking our favorite authors to put aside their authorship for the duration of this project, to engage in this particular book/journal/what-have-you on different terms. It’s a playful thing at heart, and I want authors to engage in it in that way.

It is also strange and intimate what happens when you ask people to work with you, to be in your circle, in this odd way, and we are interested in that act of unearned generosity or faith. There are always problems with gate-keeping, with editing, with privileging one voice over another, and this project puts pressures on those seams in a way that I hope will be revealing, and that I hope will work.

JT: I listen to/watch many author interviews, and something I’ve noticed is how surprised writers can be by the things that others find in their work. Writing fiction is largely intuitive, I think, as well as the revision process, and while major motifs are often intentional, other aspects of the work just kind of sneak in from the subconscious, or the part of the brain that thinks abstractly, that doesn’t quite focus on words. So when a great book is written, and everybody reads it and then someone sits the author down for an interview, they ask her all of these questions, to which she ends up replying, “Yeah, that just kind of happened,” or “Sure, I can see that.”

In this way, themes seem to emerge that the author is not entirely in control over, and when you look at several works from within a given time period, it’s even easier to draw lines between those unconscious themes. To answer your question: we want to see work that is good, to identify those unintentional unifying themes, and to thread it together with other work with similar sub- or unconscious trajectories.

November 20th, 2013 / 12:00 pm

On David Markson and Ben Marcus: An Interview with Ben Marcus

[Note: In 2000, Albert Mobilio of Bookforum asked Ben Marcus to interview David Markson. Though questions were sent, the interview was never completed. In 2012, after reading the questions on benmarcus.com, I decided to redirect them (with modifications) to Marcus himself. The interview took place via email.]

David Markson (1927-2010) was born in Albany, New York, and spent most of his adult life in New York City. His novels include Springer’s Progress, Wittgenstein’s Mistress, Reader’s Block, This Is Not a Novel, Vanishing Point, and The Ballad of Dingus Magee.

Ben Marcus is the author of The Age of Wire and String, among other books. His new book, a collection of stories, will be published in January of 2014.

Interviewer: Do you consider exposition to be deadly, inert territory?

Ben Marcus: There’s the infamous rule fed to beginning writers that you should show and not tell, but telling is one of the great and natural features of language—it’s part of what language was invented to do. It’s just that when telling is done badly—”she felt sad”—it’s conspicuous and embarrassing, it works only to remind us of the insufficiency of the mode. I always dislike hearing this rule, even if I understand why it’s given, but Robbe-Grillet is a perfect refutation of it. Sebald, Bernhard, Kluge, Sheila Heti. And of course Markson himself. Even the great narrative writers use exposition in masterly ways: Coetzee, Ishiguro, Eisenberg. READ MORE >

February 18th, 2013 / 3:19 pm

An Interview With John Tottenham

I met John Tottenham at a party hosted in an arcade in March 2012. He approached my friend and asked for a beer from the case she was carrying under her arm. “Let me have one of those,” he said in his British accent. She looked over to me, rolled her eyes and begrudgingly handed him one. “Yes, thanks,” he muttered, pivoting quickly to wander away.

I met John Tottenham at a party hosted in an arcade in March 2012. He approached my friend and asked for a beer from the case she was carrying under her arm. “Let me have one of those,” he said in his British accent. She looked over to me, rolled her eyes and begrudgingly handed him one. “Yes, thanks,” he muttered, pivoting quickly to wander away.

“What an asshole,” my friend mumbled.

I later saw him standing in a dark corner, alone, his eyes half-drawn, leaning on a pinball machine. He looked absolutely miserable. I laughed to myself. His display soothed my own misery. I had been looking for a way home since I arrived.

Six months later, John’s second collection of poetry – Antiepithalamia: And Other Poems of Regret & Resentment – was released on my press, Penny-Ante Editions.

I spoke with John via email.

***

Rebekah Weikel: Your work seems to be embraced by people who don’t normally read poetry.

John Tottenham: Which automatically dooms it to obscurity. All poetry, of course, is automatically doomed to obscurity, but to produce work that is accessible is to make it inaccessible to critics. It leaves them with nothing to do. And the critic has pulled off the outrageous feat of raising himself to the level of the artist and somehow making himself indispensable. But if there’s a direct line between poet and reader, then the critic becomes irrelevant, it could drive them out of business. Clarity is also anathema to people who are steeped in critical theory. The waters must be muddied to make them appear deeper, to give the serious readers and theoreticians something to fish for. Critical theory is a lot of fun but that’s all it is, fun: precisely what it’s supposed to not be. It’s a game for the overeducated. Nobody’s going to go there for wisdom, guidance, solace.

RW: You often write in the first person, but there’s also a contradictory quality.

JT: That’s due to the thorny issue of the unreliable narrator in poetry. It’s something one can get away with in prose – which, for example, Nabokov and Iris Murdoch do very well. But it’s difficult with poetry. People automatically assume that if you’re writing in the first person, you’re being confessional, especially if you’re addressing matters of the heart. I never sit down with the intention of writing a poem about anything or anybody in particular. The way I work is more like surgery or sculpture – a long process of accumulating notes, then chipping away, taking apart, piecing back together.

Invent your monsters sparingly: a conversation with Ned Vizzini

I sat down with Ned on a Saturday. He was feeling rough, having consumed something gnarly at a dinner party the night before in an incredibly storied Hollywood Hills house. Soon after this interview, he was struck with food poisoning. Ned’s a busy guy: his book, The Other Normals, comes out today, and the TV show he writes for with Nick Antosca, Last Resort, premieres in two days. He’s also working on a movie with Nick called Woogles, and writing a series of middle grade novels with Chris Columbus (of Harry Potter fame). And he’s a relatively new dad. Below is a transcript of our conversation, Ned drinking down gut-calming tea…

I’ve known you since you first came to LA, and I wanna know if there was any event in particular that coincided with you starting this book.

Yeah. There were two things about a decade apart. One was towards the end of high school. I was out with some friends, hanging out in the park. And I hung out with a lot of Russian kids in high school. And I had a shorter, more wily Russian friend, who’s in my first book. His name is Owen. I also had a taller, bigger, more militaristic—

A Dolph Lundgren?

In that vein. He ended up joining the military. He’s the person who told me that the US military still trains against the Russians, that when you’re doing an exercise in the military, you’re still—

Fighting the commies.

Yes. And I asked him why, and he said, “Because we’re the baddest motherfuckers around.” READ MORE >

Ken Sparling’s The Serial Library: Overview and Interview

[Guest Post: Greg Gerke]

Ken Sparling is a writer. He works in a library in Toronto. He has written six novels. His latest is Intention, Implication, Wind from Pedlar Press. His first, Dad Says He Saw You at the Mall, published by Knopf in 1996 will be reissued by Mud Luscious Press in August.

Over at BOMBLOG, a deep interview with one of the best & bravest: Jarret Kobek. Conversation includes: ATTA, Disneyland, fiction/fact, youngwriterfear, culture bends.

Street-Side, Bedside, Broadside: An Interview With Shannon Cain

The Necessity of Certain Behaviors

The Necessity of Certain Behaviors

by Shannon Cain

University of Pittsburgh Press, 2011

160 pages / $24.95 Buy from Amazon

Stories in Shannon Cain’s The Necessity of Certain Behaviors pair exhibitionist events and their three-ring tableaus with characters who typify “marginal,” yet who nonetheless surprisingly assert not only their outsider status, often in correlation with their sexualities, but also their complexities—a young lesbian ventures to the set of The Price is Right to meet her father, Bob Barker, only to find not parental but sexual identities challenged; a mayor’s wife endures the scandalizing of her sexuality after she is caught masturbating in the YMCA’s shower room, only to find that her new relegation to sexual deviant has allowed her singular insight into victims of the myriad sexual minefields in her community—the cumulative effect of these stories also achieves a reversal: common notions of taboo or freakishness gain warmth and humanity, while the normative culture unveils its crippling deformities. Cultural critique couldn’t have a more compelling and sophisticated face. In an era often favoring equivocation as a substitute for vision, this collection is clear: take a stand, make it compassionate. Others agree, of interest to note: American Literary Review, American Short Fiction, Colorado Review, Massachusetts Review, Southwards, Tin House, The O. Henry and Pushcart Prizes, the National Endowment for the Arts, and The Drue Heinz Literature Prize.

January 20th, 2012 / 12:00 pm