The Strickland-Needleman Carousel

Hey guys, it’s “ZZZIPP,” from the comment section here. I wrote the following essay for HTMLGIANT in December, but never sent it along to anyone. It’s a response to all of the Garrett Strickland misogyny stuff that was happening then, but it is also really personal which maybe explains why instead of ever sending it along I sat on it like a scared dumb bird.

HTMLGIANT has meant a lot to me over the last six years (I was lurking at the very beginning), and I want to pay tribute to that somehow. I think in some ways this essay is relevant to certain discussions which have taken place since it was announced that HG was closing (i.e.: the idea that it is “better” for indie literature to have the “HG boys club” shut down) (because fuck that).

Thanks again, though, everyone. This was a great community. I really can’t stress enough how important HTMLGIANT was to me, in all kinds of ways, even if I mostly engaged as a “photon.”

***

I haven’t read Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans, but for a while I think I wished Stein was my grandmother or my encouraging older neighbour, and I bought a lot of her books all at once and took the rest out of the library. They sat on my coffee table and on my couch and I liked to think that their mere presence was making me a better person and a better writer. I read a few of them, but I never made it very far in Americans. One day I hope to. I must have read the first page twenty or thirty times.

Once an angy man dragged his father along the ground through his own orchard. “Stop!” cried the groaning old man at last, “Stop! I did not drag my father beyond this tree.”

It is hard living down the tempers we are born with. We all begin well, for in our youth there is nothing we are more intolerant of than our own sins writ large in others and we fight them fiercely in ourselves; but we grow old and we see that these our sins are of all sins the really harmless ones to own, nay that they give a charm to any character, and so our struggle with them dies away.

When I told the woman I was seeing at the time that I wished Gertrude Stein was my grandmother or my aunt she told me that she thought everyone did at some point in their life. I felt pretty good about that, because she was five years older than me and because she used to be my teacher, and I thought it meant something that I had said something that had resonated strongly with her.

Now I can see all of the problems with that.

25 Points: Sprezzatura

|

Sprezzatura

by Mike Young

Publishing Genius Press, 2014

132 pages / $14.95 buy from Publishing Genius

|

1. Deep down he thinks he’s too much of a redneck to have got into Husker Du.

2. Syntax 1: His syntax is fascinating. Someone – can’t remember who – once said that ‘a poem should be a machine for re-reading’ and that’s what you do here. You read, you skate across the surface and then you re-read and it’s different the next time and you can’t get bored.

3. Syntax 2: Because of this, it sometimes seems like he’s put a real long scroll of paper into a typewriter emulator and just kept on Benzedrine-typing until he was finished.

4. Don’t get carried away with the Benzedrine though. There’s something else going on here:

“Often I throw a tennis ball against the wall and hope

the people downstairs believe more people exist

above them than really do…”

There’s a bit of craft at work here. Don’t get carried away with the Benzedrine. This isn’t just typing.

5. ‘On the bus, I pass through unobtainable wi-fi’ might be one of the best lines I’ve heard to sum up now, right now.

6. There are things here in this book. Things everywhere. Nouns.

7. There are unfashionable adjectives with fashionable nouns and fashionable nouns with unfashionable adjectives everywhere here.

8. Mike Young is a poetic phrase-maker in a way you don’t see too much in contemporary literature/Alt-Lit etc. He’s bringing phrase making back and making it cool.

9. I want to make a phrase now but you know you can’t just make a phrase just out of the blue as easy as you might think, it’s hard. If you plan it too much and try to think of a noun and an adjective and put them together the only noun you end up thinking of it ‘sea’ and the only adjective is ‘blue’ (or if you’re feeling revolutionary ‘green’) and that was all well and good 700 years ago but now it’s just some blue or green sea that isn’t even good enough for a corporate advertising slogan advertising shower gel let alone a book of writing/poems. So, it’s hard making phrases. It’s an art form. It’s easier to consciously make a bad one. This book is full of none-bad phrases. Here’s some:

10. ‘…imported mango soda’

October 20th, 2014 / 12:09 pm

25 Points: The Pedestrians

|

The Pedestrians

by Rachel Zucker

Wave Books, 2014

160 pages / $18.00 buy from Wave Books

|

1. The ‘Once upon a time…’-style tone of the beginning of this book reminded me of the short story ‘Clay’ in James Joyce’s Dubliners and what he or someone called the ‘marmaladey-drawersey’ tone it was written in.

2. I really like the phrase ‘sublet bed.’ Sublet properties and the whole poetry of the rented house concept are so often commented on but not sublet beds. Hurray for this.

3. To return to the style and tone for a moment, if we may…(hey that was really formal for a moment wasn’t it, cool) I really like what I’m going to call the circumlocutory descriptions here such as ‘She had a small copper wire inside her. This made conception highly unlikely.’ when she could have said ‘coil’ or ‘intrauterine contraceptive device.’ This starkness really makes me laugh for some reason. In England, there used to be books called ‘Janet and John’ books for small children that used this kind of tone to help the kids learn how to read. They didn’t mention coils or IUCDs but I really think that style transplanted to adult life is cool.

4. ‘Every day she watched the UPS truck come toward her up the/road, make a three-point turn into the driveway before hers,/and pull away’

This is beautiful, man. I can’t say more about it than that.

5. ‘They had not known each other when they were teenagers but/when the radio with the human genome played Phil Collins it/was 1985 bar mitzvah season all over again.’

I have no idea what a radio with a human genome is but the imagery is fantastic that’s just my point I suppose, that’s just my point about this book, the imagery is delicious throughout.

6. Such juxtapositions. Babysitters, Buddhist monks and pole dancing competitions. The world and this book are full of such juxtapositions.

7. Another reviewer worried about this book. They worried about how the main character who lived in the most expensive city in the world (New York) and had trips to Paris and an apparently idyllic bourgeois life with husband and children and so on and yet complained all the time. They worried how this might be taken perhaps. Whilst my own working class proletariat background could go probing into this with my bullshit-detector, instead I was reminded of DFW and his thoughts on his, albeit slightly earlier, generation and how despite all the opulence everyone was still so lonely and miserable and how much of an interesting question this still is (even now the middle-classes have discovered Occupy in their gap year).

8. I’m defending it but it’s ok to worry about that too, I think it’s a valid point. Marxism is one of the better lines of enquiry for me.

9. I have a real affection for the poem called ‘Real Poem’ because it neatly and concisely parodies Poetry (that’s poetry with a capital P) and all its big profundity and arrogance.

10. Reminds me I haven’t had babies yet.

October 17th, 2014 / 12:00 pm

I Don’t Want to Want to Win: A review of Mathias Svalina’s Wastoid

Wastoid

by Mathias Svalina

Big Lucks Books, 2014

166 pages / $12 buy from Big Lucks Books

John Berryman wrote in a letter to Allen Tate, “I don’t write these damned things willingly, you know,” an exclamation that fits the vertiginous, character-addled world of The Dream Songs. Certain writers demonstrate this possessive spirit effortlessly, and Mathias Svalina fits in among them in perfectly discordant harmony. Wastoid, his latest collection from Big Lucks Books, has crawled inside the desiccated body of the Sonnet and formed an impenetrable shell from its remains. Like The Dream Songs, Svalina absorbs the personal into a visionary metamorphosis of the real. They both discard tight form to maintain the bare mechanisms of the sonnet. In Wastoid, men swamp to and from the path to gaze into mirrors, open doors into other doors forever, tell their shitty dads to fuck off, and eviscerate themselves to gift themselves to the lover.

Early on, Svalina gives us two aesthetic choices—substance or form—on how to “tame the unrammable will,” a nod that feels self-conscious, an impossible promise. The unrammable will, like Berryman’s immutable drive for substance and form, is a concept that gains traction from isolation. And isolation, more than in any other poetic form, carries a potent smell in the sonnet. While I don’t want to convince anyone that this early moment is manifesto’s sneaky thread, it points to a duality that is signature in these poems, a duality also signature for the sonnet. The lover is the volta sluicing the flood, spilling the guts, trapping the speaker between water and whale. Any other feature of the sonnet falls to the wayside, because, in this heightened realm of lovers all called “Wastoid,” it is only the slaughter of arguments that count for anything.

Most of the poems organize themselves around the lover’s growing imperialism, fame, opposition, deterioration. Pick your poison, the lover seems to say, as their agency bloats into objects while the speaker flattens under the power of decorum, becoming more and more corporeal. The lover is an obstacle when the speaker is crushed beneath doors. The lover is a window when the speaker is only skin. The lover is a trampoline when the speaker is a “canyon killing a praying man.” The lover is a tinfoil quilt when the speaker splits into two writers. Steeped in the logic of the poems, such declarations make perfect sense. We know that the subject-predicate is at war with itself, and the battle is pathetic and terribly effective. Take this poem in full:

In “Dreamsong 88: Op. posth. no. 11,” Berryman concludes “I didn’t hear a single word. I obeyed.” We understand authority to work similarly in Wastoid. We are not made complicit to the laws of Svalina’s verse, though they circle in curious carousel around a central heartbreak. If there are laws, they exist in a trail of essentialized anguish: As above, “There are so many things that command the attention of men”; elsewhere, “To immerse oneself in another man is to become a contraption,” “It is fear that makes the world so solid,” “Even marvelous things can be effortlessly forgotten.” Most poems carry similar assertions. Svalina ballasts his domestic and nautical imagery with accessible phrases like these, and through this negotiation of reason and landscape do we find ourselves clasped entirely in his spell.

Nobody in any relationship ever wins, though the heroic sonnet might masturbate itself into a frenzy of false victory. This is how the poet obeys. Shakespeare said in one of his sonnets to a young dead boy, “For having traffic with thyself alone / Thou of thyself thy sweet self dost deceive.” Gross, Shakespeare, pull yourself together. Svalina is as alone when he writes, “I spend most of my day in the office looking at porn. In porn love is always demonstrated: one man comes on another man’s face. One man comes on another man’s face—it is like forgiveness and the photographer is the priest.” Svalina deconstructs his loneliness in these banal settings, fuses it with other more wild lonelinesses so both can resist forgiveness, pornographic or fatalistic or otherwise. Always there is a sense that to say anything is to say every version of its self-destruction:

Svalina is not afraid of the more Romantic imagery associated with the sonnet because of the ease of dismantling it: Time, Light, Hearts, Nature/Naturer, Blood. They exist in the same terrain as Home Depot parking lots, bear genitals, and the Chicago Manual of Style. The lover transforms only when these essentialized ideas of Time and Light and Nature touch this other suburbia. Sometimes, the lover is cruel, a result of the trope out-troping the trope. Sometimes the lover feels like Prince and we can’t hate him because he sings against the insect stings and horses, “I want to be your brother / I want to be your mother and your sister too / There ain’t no other / That can do the things I’ll do to you.” In either case, this is a book chock full of men, writhing and fucked inside a place that can no longer writhe or fuck. Out of the heavily guarded images, we are given these manic parables of disorder. The men roam forever sick inside the seasons of this disorder. It has been a long time since I’ve been this excited about a book made exclusively of men. Svalina can’t help but expertly turn phrases inside out, resolve to find their invisible meanings. Each poem is its own collection of poems, its own annihilation of his collection of poems. Like men they have the power to deny or condemn as they have the power to enable and motivate further. The simple quiet of his wasted world goes on and on: “The ATM screen tells me press enter to exit. I must enter to exit.”

***

October 16th, 2014 / 10:42 pm

25 Points: Ozma of Oz

|

Ozma of Oz

by L. Frank Baum

HarperCollins, 1989

272 pages / $6.95 buy from Amazon

|

1. This past year, my 5-year-old has been obsessed with me reading The Wizard of Oz to her over and over and over. While I have loved that book for decades, I reveal to her it is a series – there are more!

2. So we begin book two in the Oz series, The Marvelous Land of Oz. Which turns out to not be marvelous. “Where is Dorothy?” my daughter asks. In fact, Dorothy is nowhere to be found. Instead of Dorothy, there is a sorceress who is trying to force her ward Tip to drink a potion that will turn him into a statue. The sorceress is kind of scary.

3. Though the sorceress is not why we stop reading the book.

4. We stop reading when the ridiculous all-girl Army of Revolt storms the Emerald City, making the men mind the children and do the housework, only to get scared off by mice.

5. We move onto Treasure Island which I realize, early on, is not appropriate for a 5-year-old because of large quantities of murder and rum, finally settling upon Pippi Longstocking which, despite the heroine’s coffee habit and dead parents, appears a good fit. Then it is back to The Wizard of Oz.

6. Then instead of rereading The Wizard of Oz again, I suggest why don’t we try book three in the series (Ozma of Oz). The book is #83 on the School Library Journal’s list of the best children’s novels ever. Unsurprisingly, The Marvelous Land of Oz is not on the list. Still, I am nervous, making my daughter nervous. Reading bad books is an awful experience, but reading bad books aloud to your child is much worse, as it takes longer and skimming is difficult to do.

7. In the case of Ozma of Oz, There was no need to be nervous. It turns out I love this book. I have loved this book. This is the book with the lunch-box tree. “The tree seemed to bear all the year around, for there were lunch-box blossoms on some of the branches, and on others tiny little lunch-boxes that were as yet quite green, and evidently not fit to eat until they had brown bigger. The leaves of this tree were all paper napkins, and it presented a very pleasing appearance to the hungry little girl.” Inside the lunch-box was, “nicely wrapped in white papers, a ham sandwich, a piece of sponge-cake, a pickle, a slice of new cheese and an apple. Each thing had a separate stem, and so had to be picked off the side of the box…”

8. But the tin dinner-pail tree is even better. The dinner-pails grew on another tree and inside each pail was a thermos of lemonade, plus “three slices of turkey, two slices of cold tongue, some lobster salad, four slices of bread and butter, a small custard pie, an orange and nine large strawberries, and some nuts and raisins. Singularly enough, the nuts in this dinner-pail grew already cracked, so that Dorothy had no trouble in picking out their meats to eat.” I remember these trees. These trees are one of the most vivid memories of reading I can recall as a child.

9. I think it was a tragedy of extreme proportions to the child-me that such trees were nowhere to be seen in my Chicagoland home. The lack of such trees was proof that there had been some mistake and that I was living in the wrong world.

10. This is also the book with Princess Langwidere who has a room full of velvet lined cupboards and, inside each cabinet, is a different head that she can put on or take off whenever she likes. Unfortunately, when Dorothy is visiting, the princess puts on the mean head.

October 15th, 2014 / 12:58 pm

Formerly Anonymous Review: Zone

|

Zone

by Mathias Énard

Open Letter Books, 2010

517 pages / $16.95 buy from Open Letter Books

Rating: 8.0

|

A French-born Croatian boards a train in Milan. He stows an overfull suitcase beside his seat. He’s hungover, buzzed on amphetamines, and pursued by ghosts. Outside, it’s raining and cool. As the train leaves the station, this Croat, Francis Servain Mirković, an analyst in the French Intelligence, begins to mine the incriminating documents he carries. And as he does, he begins to melt into the Zone. The following ten chapters, spanning 500 odd pages, unravel in a single breath.

Mathias Énard, the brilliant French novelist, and winner of the Prix Decembré, employs no periods or paragraph breaks in his astounding Zone, published in 2010 by Open Letter Books. And while the novel is framed by this train ride (Milan to Rome), the inevitable plotlines recall the desperate noir of Jim Thompson, with more than a hint of László Krasznahorkai.

Énard’s “Zone” is vaguely the territory between Tangier and Beirut, (“Ceuta, Oran, Algiers, Tunis, Tripoli, Benghazi, Alexandria, Port Said, Jaffa, Acre, Tyre, Sidon,/ or else Valencia, Barcelona, Marseille, Genoa, Venice, Dubrovnik, Durres, Athens, Salonika, Constantinople, Antalya, Lattakiyah,/ or else Palma, Cagliari, Syracuse, Heraklion, Larnaka”) otherwise called the Mediterranean world, “A complex of seas…broken up by islands, interrupted by peninsulas, ringed by intricate coastlines” (Fernand Braudel); and definitively a landscape of despair, “here the mud is made from our tears.”(Charles Baudelaire)

As the spy retrieves his documents, Énard charts the history of twentieth century authoritarian violence across the Mediterranean/ Middle East. And from Ustashi’s, to Falangists, to the Baathists of Aleppo, this history is brutal.

Although Énard lays down boundaries and identifies this Zone of despair, he does not presume exceptionalism.

Instead, he emphasizes the extent to which the violence across the Zone conforms to a global system of violence, specifically highlighting the wars in the Balkans, Lebanon, and the occupied territories. Like J.G. Ballard’s terrific War Fever, he identifies these proxy wars as a predictable symptom of the current world order. Its no coincidence they play out far from the centers of global power. His observations echo Baudrillard, who famously suggested the prisons complexes of the United States obscure the inherently carceral character of contemporary American society.

When you knock around a lot of libraries, you end up reading a lot of the same. Zone is not that. Like Krasznahorkai, or Danielewski, Énard moves in darkness and depth, and he comes up with something exceptional.

October 14th, 2014 / 12:00 pm

25 Points: If I Really Wanted to Feel Happy I’d Feel Happy Already

|

If I Really Wanted to Feel Happy I’d Feel Happy Already

by Jordan Castro

Civil Coping Mechanisms, 2014

162 pages / $13.95 buy from Amazon

|

1. This book and it being read by me results in me saying that Jordan Castro is like a really cool stand-up comedian sometimes.

2. A thoughtful, off-beat, occasionally philosophical stand-up comedian who plays to small audiences of people who are ‘in the know’ but could sell out bigger shows but perhaps wouldn’t want too but might think about it a little bit but wouldn’t want too.

3. The title is another one of those fucking ace, long titles isn’t it. Have you read it (see above)? Good isn’t it. Becoming something of a tradition isn’t it – the long, good, title.

4. Castro is…no, no I’m not going to call him that. Not going to just call him by his surname like they do in reviews. It feels a bit like a teacher talking about a pupil or a factory owner (A factory owner? Fuck! What century am I in?) talking about a worker in a slightly patronising way. So, yeah. Jordan Castro is a fan of circular reasoning, it pops up throughout the book. He gets all circulus in probando (Wikipedia) on our ass all the time.

5. Or maybe he’s not a fan of circular reasoning. Maybe these things trap him and impede his life like they do with all of our lives and he finds it’s best to try and write about them to circumvent this trap slightly and if we read him we can slightly circumvent our own circular traps. Just slightly. I don’t think he’s trying to write a miracle cure.

6. This book isn’t a miracle cure. Never believe in miracle cures. They don’t exist. They’re all scams. This book isn’t a scam. This book is upfront about things, about everything that’s going on in the minutiae of everyday life. It’s not a miracle cure but it might help. Plus it’s really funny and entertaining too, which helps.

7. The tale of a character named ‘Sarah’ that starts on p.95 is the tale of everyone nowadays who is under 40 and many over 40 and soon everyone in the western world and later everyone in every other type of world (this latter depends on a few things that are currently, to put it politely, ‘in flux’ in global affairs) but they won’t all be named Sarah.

8. In this one:’got a lot of allergies/been thinking about literature/for maybe five hours’, he’s secretly thinking about the sounds of words at the end of lines like an old fashioned poet but is hiding it even though he’s made it really subtle and really good.

9. Pages 115-119 make me realise that social media is so bedded-in in America that people really do view it as part of their real identity and really do agonise about what statuses they type and how they’ll be perceived and how many ‘Likes’, ‘Comments’, ‘Notes’ or whatever it will/should get in a way that is only really just starting to happen in the UK and in a way which sometimes depresses them.

10. I read somewhere in an interview with Noah Cicero (it could’ve been from ages ago, he might have changed his opinion by now, I don’t know. Anyway, he’s entitled to his opinion) that he didn’t really rate David Foster Wallace as being too much to do with Alt-Lit type of stuff but point number 9 makes me want everyone to read this essay by David Foster Wallace on television and then for someone else, someone who is still alive, and someone who, like me, doesn’t have to work full-time to re-write that essay, updating it for today’s social media landscape and for us all to see how prescient it was in the first place.

October 13th, 2014 / 12:00 pm

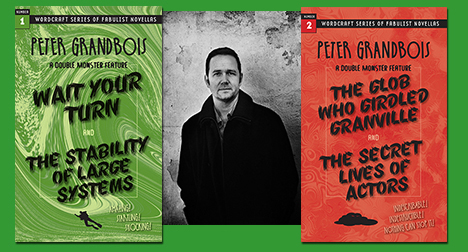

Reading the B: A Review of Peter Grandbois’ “Double Monster Feature”: the novellas The Glob Who Girdled Grandville and The Secret Lives of Actors

The Glob Who Girdled Grandville &

The Secret Lives of Actors

by Peter Grandbois

Wordcraft of Oregon, October 2014

There’s both a blessing and a persistent sense of cursed lack to ignorant reading, as when the reader has little or no foothold in the allusionary worlds that propel a given story, but, likewise, when the narrative doesn’t require any specific referential knowledge for engagement. Peter Grandbois’ “Double Monster Feature” of two, short novellas, The Glob Who Girdled Grandville and The Secret Lives of Actors, is such a collection, operating on a parodic platform while also completely rewriting this platform. Grandbois’ two main characters are B movie icons of the 50s—The Blob and The Thing—but rather than relegating these creatures to the shadowy sidelines, Grandbois explores them from the inside out, divulging their confusions, desires, and inchoate pathos. And even for those readers like myself, who are mostly unaware of the works’ cinematic histories, both stories unfold quite nicely on their own, doing so by cluing the reader via references to their filmic origins through tacky tropes and déjà vu moments of cliché, touching on our timeless and cheesy yearn for kitsch, for that passé sentimentality deeply ingrained in some collective pop-culture consciousness. Of course, and necessarily, Grandbois explodes these frameworks even as he builds upon them, breathing a new, complex literary life into both narratives, so that the thrill is one of uncanny insight and surprising tenderness.

A Rilke epigraph lifts the curtain on these features—“Oh, this is the animal that never was…,” which speaks to the troubled paradox of Grandbois’ project—humanizing the monster; as from The Glob:

Let us stand clear now and let the troubling story unfold, as we know it did from the newspaper accounts that came after. Of course, we don’t have all the details. We don’t need them. We know in our hearts what happened, what had to happen given the circumstances … Of course, even with our strong storyteller’s sense of empathy, we’ll never fully understand the mysterious life cycle of such a creature. All we really know is that he arrived here on a meteor, a mere babe of an amoeba fourteen short years before. His first experience of life one of hostility as that old man who discovered him poked him with a stick.

Grandbois’ two protagonists, as Rilke suggests, attempt to fashion the real through the unreal. Instead of letting his monsters remain ineffable, opaque, and struggling against nothing but impulse and base survival, Grandbois rescripts these creatures; even as their forms pervert physical paradigms, they are hyper-effable, all too finite, and this is their doomed struggle: the greatest monstrosity is being unable to grasp, only analytically mimic, human motivation and relationship. In The Secret Lives of Actors,

He walks out of the parking lot and down the street, unaware of where he’s going. Maybe she’s right, he thinks. Maybe I am the fraud. I’ll bet that bastard Hawks made me up for the movie. I’ll bet he invented the whole idea of a walking carrot … Who’s afraid of a giant vegetable, anyway? You can’t even love a vegetable because a vegetable can’t love … He wanders down Sycamore until he stumbles into the community garden … then he stops and sits among the carrots and green beans. “You’re right. I don’t belong here,” he whispers to himself. “I’m nothing but a Hollywood invention. Not even an interesting one. What would Nikki ever see in me, anyway? An actor who can’t feel. It’s like some sort of bad joke” … He spends the rest of the afternoon digging a hole for himself … Anything is better than this. This in between place. This place somewhere between life and death.

October 10th, 2014 / 10:00 am

25 Points: Gamine

|

Gamine

by Emily Sipiora

forthcoming from Pink Finger Press, 2014

|

1. This book often has a cut-up and and collage kind of feel and sometimes reminds me of Jean Luc Godard’s ‘Pierrot le Fou’ in a way that I can’t fully explain.

2. I don’t really like rhyme or half-rhyme and some of this is rhymed and half-rhymed but somehow it manages to avoid that cloying feeling that rhyme and half-rhyme gives to too much poetry. This is an achievement because most who attempt this don’t manage to accomplish it so well.

3. She’s also doing something with meter, I think, which is brave if so (I haven’t scanned it properly obviously – partly cos scanning is so subjective and party because I didn’t want to). I gave up meter myself, I didn’t like how it mangled my syntax, same with rhyme and the need for a lot of what more traditional poetry bods call masculine endings (stressed syllables at the end of a line). Maybe this type of stuff is due a return. I don’t know. Emily pulls it off pretty well, though.

4. Elliott Smith is a welcome presence in anything that I experience and he pops up here. Sometimes directly quoted and sometimes in bit like ‘Mr Amiability’ (although while I was writing this my girlfriend was asking me to put the HDMI on the TV and it made me think how Elliott Smith could’ve even sung HDMI and made it sound amazingly melancholic. I know the writer likes him and I think he’s a good person to like which is contrary to the way in which a British tabloid recently managed to somehow implicate him from way beyond the grave in the death of British celebrity Peaches Geldolf. After seeing his legacy trotted out in such ridiculously absurdist tabloid terms, it’s nice to have him back and rehabilitated into something real and artistic and appropriate.

5. Ian Curtis pops up now. He joins Elliott Smith. There’s a theme here.

6. “Anyone up at 3am was either in love or lonely” is a great line.

7. “I live in your voicemail now” another great line.

8. There are a lot of great lines here.

9. This author is pretty young, like 17 or 18 or something, I think. This isn’t her first book which is pretty impressive in itself. I was going to say she’s ‘pretty mature for her age’ until I realised it made me sound like an old ageing aunt or something. Maybe this is how it is these days but if she’s getting this kind of thing out there now already, what can we expect in years to come? I’m looking forward to it, whatever it is. All you other Alt-Lit writers, you’re getting old, man! (That was a joke mostly on myself, to be fair).

10. There’s stuff in here that is kind of cut-up image macros of Wikipedia. I read somewhere that someone ‘advised’ Emily to stop putting photos in her books because it makes it seem more like a blog. I think she should put whatever she likes in and perhaps this person maybe hasn’t been looking to closely at the alternative literary scene of the past 5-8 years.

October 9th, 2014 / 12:00 pm

25 Points: Sorrow Arrow

|

Sorrow Arrow

by Emily Kendal Frey

Octopus Books, 2014

92 pages / $12.00 buy from Octopus Books

|

1. I read Sorrow Arrow in June.

2. “What was the last book you read/what was your favourite, lately?” A friend of mine who was out of town for the summer sent me this text message. I told her it was Sorrow Arrow by Emily Kendal Frey. When she got back into town a few months later I loaned it to her.

3. If you’re like me, once a year or so, you read a book that makes you rethink the way you’ve been writing entirely and you come away from it sure beyond a shadow of a doubt that the only way to write is the way that writer does it.

4. Sorrow Arrow was one of those books. When I was finished with it I just felt the entirety of all the poetry I’d ever written pass into obsolescence.

5. My first exposure to Emily Kendal Frey was when we both had prose poems published in Issue 6 of Banango Street in January. I felt privately certain they only published my poem because it was a prose poem roughly the same length as hers and together the two felt like they were kin somehow — cousins of about the same age who look just like each other but only met for the first time in their late teens. Hers was the more successful cousin by far.

6. I added her on Facebook and a few weeks later she posted as a status the sentence “She is born!” and the book’s cover, a faceless blankness wrapped in a green wreath, whirling, encircling sheaves of grass.

7. Two weeks later she posted that the book was available for order and I ordered it immediately.

8. Here is one of the poems: “A radiation plume is making its way to us/We write it down so we won’t think/Lap dogs sprinkled with acid snow/I got on the plane and sat back/Out the window I regretted complaining/I’m sorry I wasn’t able to get inside your color/The sky was cobalt, deafening/I die so I can live/Outside category” (p. 57)

9. At the centre of Sorrow Arrow is a tragedy. There is a tragedy at the centre of every great book of poetry, I imagine.

10. Frey’s tragedy runs through the poems—none of which have titles—like a skein of gold, a vein you can see just beneath the skin, a tungsten wire that glows bright and hot to the touch.

October 6th, 2014 / 12:00 pm