25 Points: 7 Days and Nights in the Desert

7 Days and Nights in the Desert (Tracing the Origin)

7 Days and Nights in the Desert (Tracing the Origin)

by Sabrina Dalla Valle

Kelsey Street Press, 2013

88 pages / $13.00 buy from Kelsey Street Press

1. Sabrina Dalla Valle is an alchemist, a sorceress, scribe.

2. The role of poet as spell-caster/magician/mystic is seen through these pages. If it’s not clear, how can I say this?

3. everything is indication of moisture in a landscape– not just density of species, but also the shape of the earth.

4. How to propagate a landscape?

5. While reading Dalla Valle’s book I recall being ten years old, casting my first spell.

6. Poetry should transmutate; cause a change from one form, nature, substance, or state into another. In other words to transform the temporal existence.

7. as if not yet fully human

8. Meditation requires practice. There’s an alchemy at work here in these lines

9. Reflect upon the nuances of the question of: what gives us life?

10. like filaments

11. writing is read by the dream

12. I ordered feverfew and other herbs from a catalogue and had it shipped via Cash on Delivery (C.O. D.), a service that no longer exists

13. At the skin of your breath is poetry

14. Photons are their mirror

photons can change into each other:

presence into image, image into presence.

but they can form into mirror planets

and even mirror stars

15. My mother wrote the mailman a check

16. Poems are the path of veins. There’s a ________________ at work here

17. Like poems representing metals

18. Meditation requires practice

19. the principle of combustibility contained within the artist’s line

20. has been swelling in my stomach

21. the charge between two words passed back and forth between lovers

22. can touch you

23. can touch

24. embroidered sky

25. If I reach out far enough I can touch that ten-year-old self through the fickle of curved stars

Mg Roberts’ bio:

Born in Subic Bay, Philippines, Mg Roberts teaches writing in the San Francisco Bay area. She is the author of not so, sea (Durga Press, 2014), a Kundiman Fellow, and Kelsey Street Press member. Her work has appeared in the Stanford Journal of Asian American Studies, Bombay Gin, Web Conjunctions, and elsewhere. She’s currently working on an anthology of critical essays on avant-garde writing for/by writers of color.

May 20th, 2014 / 12:00 pm

Painted Cities by Alexai Galaviz-Budziszewski

Painted Cities

Painted Cities

by Alexai Galaviz-Budziszewski

McSweeney’s, March 2014

180 pages / $24 Buy from Amazon

Painted Cities is the kind of book that gives me hope. This isn’t the best thing I can say; the best books I read take away my hope altogether, blow me away so thoroughly that I can’t imagine ever writing anything that can even appear in the same medium as them. The best books crush me, leave me in awe.

But hope is not the worst thing I can say, either. The stories in Painted Cities are loose and optimistic. As promised by the sticker plastered to the back of the book, they chart a (usually) first-person narrator’s coming of age in the Pilsen neighborhood of Chicago, where illicit trysts are as likely to happen in the adjacent apartment as shootings are to take place just down the street. The first full story in the collection—it’s preceded by a three-page short, the likes of which are peppered throughout the collection—works in the continuous past, out of scene, for ten pages. The narrator and his sister used to pan for gold in the gutter; they would find 7UP tops and cut their hands on shattered glass. We hear about the neighborhood in an almost endless series of sentences like these, this one describing the parties neighborhood kids had around unscrewed fire hydrants: “From where our pump was, the kids down the block looked like miniature figurines, pet people running about, yapping, like windup toys.” It is only in the final three pages that a nearby apartment building burns down, and the narrator’s family piles into the street to reflect on the ruin that almost seems built in to the tightly-packed Pilsen apartments.

This is what I mean when I say loose. The stories here don’t seem overly concerned about developing a plot. They seem unworkshopped, something that bothered me at first and later, when I thought about it, turned into a virtue. It’s clear that the point of Painted Cities, like its presumable namesake, Calvino’s Invisible Cities, is more the environs than the action that occurs therein. It strikes me as victorious—it gives me hope—that a debut story collection can survive, even thrive, on the sheer, naked power of wonder at the neighborhood the author grew up in.

Some other cases in point. In “Freedom,” the narrator and his newfound friend Buff climb to the top of an old pierogi factory and build a fortress out of scrap wood, imaginatively thriving there until some gangbangers climb up and tear it down. “Maximilian” proposes, “I want to tell you three memories of my cousin Maximilian,” and goes on to do just that. “Blood,” in the guise of a barroom narrator speaking to a second-person listener, riffs on bar etiquette and interpolates events that took place in the bar and the surrounding neighborhood. The five-page “Supernatural” describes the uncanny light that wafts from a polluted river at sundown, and the crowds that are drawn to it.

Even the titles here give off a sort of pleasant naiveté, the possibility that experiences might be reduced to a single salient buzz-word. Of course, the stories’ depiction of a world that is self-consciously less than perfect puts the tongue of titles like “Growing Pains” and “Ice Castles” fairly well in cheek. But still, you see an almost overly earnest impulse in Galaviz-Budziszewski to redeem Pilsen, to make something brighter emerge from its grittiness. At the end of “Blood,” we get:

You got a good friend, that means you do anything for them. That’s being stand-up….A friend’s all you got, they’re family, and once you don’t got family, tell me, motherfucker, what do you got? (128)

At times I’m skeptical. Galaviz-Budziszewski’s biography in the back of the book is self-consciously external not only to the academy many of us are used to but to the publishing world at large. It reads in full:

Alexai Galaviz-Budziszewksi grew up in the Pilsen neighborhood on the south side of Chicago. He has taught in the Chicago public school system and is currently a high school counselor for students with disabilities. In his spare time he builds and repairs motorcycles.

I worry that Galaviz-Budziszewski is trading on his worldliness here, trying too consciously to cultivate a persona that is qualified to speak about the struggles of inner-city life. But when you get the object in your hands, you’ll forgive him quickly. Painted Cities is a beautiful, short book, 180 pages between hardcovers (no dust jacket) that are illustrated wonderfully by Joel Trussel. Galaviz-Budziszewksi is so trusting with his narration, so endearingly willing to pull a thin yarn the length of twelve pages, that you can’t help but like the guy.

And when you get stories like “God’s Country,” the longest in the collection by far at thirty pages, you begin to think that you might be able to do this too. This is where the hope comes in. The story follows a boy who discovers one day that he is able to bring dead creatures back to life. He and his friends spend a summer reviving pigeons, finally bring an OD’d gangbanger back from the beyond.

The end of the story felt like too much to me at first, the kind of sweet wrap-up that a young writer wants to give their stories to cauterize frayed ends. Even today, the retrospective narrator says, when he finds a dead bug in his bathroom he’ll pretend to be his supernaturally powerful friend:

And just for fun I’ll close my eyes, open them, and touch the dead body. I’ll hope that my finger will give life, that I’ll feel again what I felt when I was fourteen, when, in this whole damn neighborhood, among all this concrete, all these apartment buildings, church steeples, and smoke stacks, we were somebody.

But then I let go of my skepticism and let the story be what it is. What is it? A guy remembering what it was like to grow up and wishing, despite the turmoil, that he was still there. That’s something I can appreciate, long string of nostalgic commas or not. And it’s something—this is my favorite part—that I think I might be able to do someday too.

***

Dennis James Sweeney‘s writing appears in recent issues of Word For/Word, Harpur Palate, Unstuck, and Fjords Review‘s Monthly Flash Fiction. He lives in Corvallis, Oregon. Find him at dennisjamessweeney.com.

May 19th, 2014 / 10:00 am

Living With a Wild God by Barbara Ehrenreich

Living With a Wild God: A Nonbeliever’s Search for the Truth about Everything

Living With a Wild God: A Nonbeliever’s Search for the Truth about Everything

by Barbara Ehrenreich

Grand Central Publishing, April 2014

256 pages / $23.50 Buy from Amazon

The first thing I read about Barbara Ehrenreich’s Living With a Wild God, out last month from Hachette Book Group, was the Amazon blurb. There was no question about whether I would read a book by Ehrenreich (Nickel and Dimed, Bait and Switch); she has already, for my money, proven her inherent cultural worth, despite the fact that I don’t always find her arguments entirely convincing. I turned to the blurb merely to identify the topic of this latest offering, and, since my mind was already made up to buy it, I skimmed. A few phrases jumped out, namely “In middle age, she rediscovered the journal she had kept during her tumultuous adolescence…” and “bringing an older woman’s wry and erudite perspective to a young girl’s impassioned obsession…” Those bits, along with the book’s subtitle (“A Nonbeliever’s Search for the Truth About Everything”), were enough for me to imagine the scope of the entire book, which went something like this: Teenaged Barbara keeps a diary that asks questions like “Is there really a God?” and “Should I go to second base with Steve C. after homecoming?” Older Barbara rereads this sweet, mortifying relic and brings some hard-won, grown-up wisdom to the whole ordeal.

I could not have been more off base (or, perhaps, worse at skimming). Living With a Wild God does include small excerpts from some of Barbara’s papers, but calling them a “diary” would be a real stretch, as would calling Barbara anything as conventional as a “teenager.” Barbara was exceptional (her father claimed to have an IQ of 187, and though she says this “put the rest of us at the level of insects by comparison,” you certainly get the sense that she didn’t fall too far from the tree), and her teenage papers are filled with commentary on things like quantum mechanics and the work of Sartre, Camus, Nietzsche, Tchaikovsky, and Borodin (just to name a few). At the age of 15 or 16, she becomes particularly taken with chemistry, summing up the obsession like this:

I am a supersaturated solution, I’m a filter paper who’s had too much. Chemistry is the last thing I think of at night and at 6:30 AM my first conscious thought is about the occurrence of aluminum. And this is only the introduction to the preface to the beginning of the most elementary chemistry. It’s not blood in my veins, it’s a colloidal suspension.

It struck me as I was reading that adolescent Barbara is a dead ringer for Paloma Josse, the twelve-year-old heroine in Muriel Barbery’s The Elegance of the Hedgehog. Both young ladies ask, via their notebooks, “What’s the point of it all?” While the question is common, these two are actually smart enough to take a serious, multi-disciplinary stab at an answer. Both find that answer to be, at least at first, fairly bleak.

One gets the sense, though, that Paloma, despite her suicidal plans, is going to be okay. Structurally, Barbery makes it clear that the child is working her way toward the lonely concierge Renée, and Paloma exhibits just enough childish thinking to lighten the mood. I spent most of Living with a Wild God, however, wanting to give young Barbara a cup of hot chocolate and a big old hug. Her childhood is atrocious. Her parents are hostile alcoholics who value “rationality” above all else, including—it seems—love. With a home life like that, it’s no wonder she became a solipsist at 14.

May 16th, 2014 / 10:00 am

Writing in Plain Sight: The Author, the Narrator and the Difference (if any)

When fiction reading is going well for me, I translate the words into something that’s both fiction and non-. Take the novel The Name of the World by Denis Johnson, which I read recently for the first time. Here’s the first paragraph:

Since my early teens I’ve associated everything to do with college, the “academic life,” with certain images borne toward me, I suppose, from the TV screen, in particular from the films of the 1930s they used to broadcast relentlessly when I was a boy, and especially from a single scene: Fresh-faced young people come in from an autumn night to stand around the fireplace in the home of a beloved professor. I smell the bonfire smoke in their clothes and the professor’s aromatic pipe tobacco, and I feel the general unquestioned sweetness of youth, of autumn, of college—the sweetness of life. Not that I was ever in love with this scene, or even particularly drawn to it. It’s just that I concluded it existed somewhere. My own undergraduate career stretched over six or seven years, interrupted by bouts of work and transfers to a second and then a third institution, and I remember it all as a succession of requirements and endorsements. I didn’t attend the football games. I don’t remember coming across any bonfires. By several of my teachers I was impressed, even awed, and their influence shaped me as much as anything else along the way, but I never had a look inside any of their homes. All this by way of saying it came as a surprise, the gratitude with which I accepted an invitation to teach at a university.

I relate strongly to the narrator, who we learn later is named Michael Reed. The amount of emotional overlap between Michael’s and my life is scary. I too held similar images of academic life, for me perhaps set in the fifties and involving more letterman sweaters, but the same otherwise. Like the narrator, it took me six or seven years to finish college, and involved three transfers. I was also impressed by my teachers, and I also never imagined seeing the insides of their homes. This is exactly what I look for in a novel reading experience, a character who’s as much like me as possible, and telling his—our—story with a compelling, authoritative voice. Telling me, in short, about me.

But at least as important as my strong relationship to the narrator is the strong relationship I feel to the author. I read the above sentences, and I feel like I know the narrator’s shadow figure, Denis Johnson, very well. How can one write of this bucolic college tableau, “Not that I was ever in love with this scene, or even particularly drawn to it,” and not on some level feel the same way? I think of actors, who have to find something relatable in every character they play, even reprehensible ones. Can a writer fake this stuff? If he can’t, then what’s really the difference between Michael Reed and Denis Johnson?

And still there’s a third level in which I feel a deep connection to this work. As a writer myself, I feel a strong professional connection to the author for these perceived overlaps in our histories and psyches. Denis Johnson is a successful—even world-class—writer, and I hope that these emotional/biographical similarities mean that I somehow—despite all evidence to the contrary—am on some kind of path to a literary career. This guy is just like me, and he won the National Book Award! I can’t help but hope, despite my age, lack of comparable publishing success and absence of completed work as riveting as, say, Jesus’ Son, that I am somehow in the same game as Denis Johnson.

So The Name of the World hit me squarely because I relate to the narrator, and the writer, and because I want to succeed like the writer has succeeded. In other words, I’m about as perfect an audience for this novel as there is.

In all my exploration of writers and writing (B.A. in English, M.F.A. in Writing, 25 years of near constant reading and writing outside of class), I’ve rarely heard anyone mention this third, professional angle to readerly empathy. I suspect this is because, back when I was in school, writers still entertained the idea that most of their audience would come from actual readers and not other writers. There were of course “writers’ writers” back then, or those authors who were read almost exclusively by other writers—David Foster Wallace comes to mind. But I still think we were largely in the Saturday Evening Post romance of the reader/writer relationship, that is, educated people sitting down with books and magazines and being sucked in by written pieces. The author Gary Shteyngart gets credited for having said, “The number of people who read serious literature is now exactly equal to the number of people who write it.” Maybe an exaggeration, but probably the healthiest angle from which to come at a literary writing career in 2014.

Despite my deep interest in the writer of The Name of the World, I wouldn’t like the book as much if it were memoir. Imagine if the first sentence of the intro paragraph were “Hi, I’m Denis Johnson,” and “Denis Johnson” replaced “Michael Reed” throughout. I would still be interested in the book, and I’d probably read it and relate to it deeply at points. But I could never fully imagine myself into the narrator’s plight the way I can with the novel The Name of the World. In other words, the memoir The Name of the World would never quite be about me and Denis Johnson the way the novel is. The fiction tag allows Johnson, or any writer, to play both hands: he can utilize a fictional narrator, which allows the reader more leeway to see herself in the character, and he can titillate with suggestions of autobiography, which allows the reader to form empathy with the writer. Somehow these two readerly perspectives aren’t contradictory. The narrator of The Name of the World is both Michael Reed and Denis Johnson, and I’m fine with that.

May 12th, 2014 / 10:00 am

Kill Marguerite and Other Stories by Megan Milks

Kill Marguerite and Other Stories

Kill Marguerite and Other Stories

by Megan Milks

Emergency Press, March 2014

240 pages / $15.95 Buy from Amazon or Powell’s

The possibility of Sweet Valley High twins Jessica and Elizabeth Wakefield having incestuous sister-sex with each other never occurred to me when I was a kid and living for those books, even though half the joy of reading them was a desire for violation when faced with all that phony perfection. I always wanted something sexual or terrible to happen, more than a kiss or someone having her bikini top untied in the pool. (The other half of the appeal was jealousy—oh to be 5’6”, blond, and have sparkling aquamarine eyes and a twin sister! Pulchritude amplified.)

So, I am grateful to author Megan Milks, who in her debut story collection, Kill Marguerite and Other Stories, writes in a letter from Elizabeth to Jessica, “I want to spend the evening watching you get yourself clean. I want to shave my head and lie in bed with you all day long. I want you to tell me you love me more each time you look into my eyes. Tell me I’m what your hands were made for, what your mouth was made for.” It’s hilarious, wonderful, mixed-up, and just how I–and probably all the other dirty-Barbie-players out there–feel about these icons. Do we want to be them, fuck them, destroy them? All at once?

April 28th, 2014 / 10:00 am

WHAT BOX? Talking with Lance Olsen on FC2’s 40th Birthday

Founded in 1974, FC2 is one of America’s best-known ongoing literary experiments and progressive art communities. In honor of FC2’s fortieth birthday, publisher Lance Olsen has generously answered the following questions about publishing, longevity, and innovation.

***

Rachel: What is FC2?

Lance: FC2—short for Fiction Collective Two—is a small, independent, not-for-profit press run by and for innovative authors. One of America’s best-known ongoing literary experiments and progressive art communities, for the last 40 years FC2 has dedicated itself to bringing out work too challenging or heterodox for the commercial milieu. Originally founded in 1974 as Fiction Collective by a handful of writers—Ronald Sukenick, Raymond Federman, and Jonathan Baumbach among them—FC2 has so far published more than 200 books by more than 100 authors.

Rachel: What does FC2 mean to you?

Lance: FC2 is an ongoing investigation into what innovative writing means—and that meaning is continuously in flux. One of the great joys for me about our editorial meetings, which take place once or twice in the fall, and once or twice in the spring, is that they make up an ongoing conversation about such troubled and troubling terms as “cutting-edge,” “artistically adventurous,” and “experimental.”

Those terms mean something else now than they did in, say, 1974; will mean something next Tuesday than they did last Monday; will mean something different to one person than to another—which is to say such terms are inherently unstable ones, open to ongoing modification, depending on who you are, where you are, what you’ve read, and so on. That is, they are terms always-already in-process.

By my lights, at the heart of them are a series of implied questions: what is narrative? what are its assumptions? what are its politics and social dynamics? its limits? how does narrative engage with the problematics of representation? identity? temporality? gender? genre? ideas of “literature” and “the literary”? authorship? readership and the act of reading in the twenty-first century?

In other words, perhaps a fruitful way of approaching a tentative definition of such narrativity—represented with respect to FC2 by such diverse authors as Lucy Corin and Brian Evenson, Cris Mazza and Amelia Gray, Michael Martone and Stephen Graham Jones, Matt Kirkpatrick and Samuel R. Delany, Michael Joyce and Clarence Major, Vanessa Place and Hilary Plum, Joanna Ruocco and Leslie Scalapino, Melanie Rae Thon and Yuriy Tarnawsky, Steve Katz and Mac Wellman, Diane Williams and Lidia Yuknavitch—might be to suggest it is the sort that includes a self-reflective awareness of and engagement with theoretical inquiry, concerns, and obsessions.

25 Points: Atalanta (Acts of God)

Atalanta (Acts of God)

Atalanta (Acts of God)

by Robert Ashley

Burning Books, 2011

208 pages / $25.00 buy from Amazon or SPD

24. When I began this review Robert Ashley was alive. In light of his death, I feel a compulsion to redraft and make these twenty-five points address something more. I want to talk about seeing Foreign Experiences and Lectures to Be Sung performed, about composition and improvisation, contemporary opera, and the intersection of music and language. Ashley’s work is full of good discussions. I’m attracted to the just-some-dude delivery style and storytelling aspects in the operas. One of my composer pals can’t follow the stories at all, and seems obsessed with the involuntary speech in Ashley’s work. Ashley’s work is so dense, and there are so many lessons that I take away from his work as a performer and writer. It’s hard to limit the discussion, especially given this kind of retrospective appreciation and the span of his work.

April 22nd, 2014 / 12:00 pm

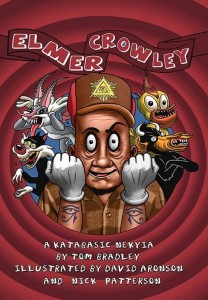

Elmer Crowley: a katabasic nekyia by Tom Bradley

Elmer Crowley: a katabasic nekyia

Elmer Crowley: a katabasic nekyia

by Tom Bradley

Illustrations by David Aronson and Nick Patterson

Mandrake of Oxford Press, 2014

134 pages / $14.99 Buy from Amazon or Mandrake of Oxford

Aleister Crowley is thinking about Germany’s late chancellor:

…my magickal child… who queefed out of my psychic vagina at an unguarded moment…[who] flopped from my left auditory meatus like a menstrual clot with incipient toothbrush mustache…

His mind wanders, logically enough, to Esoteric Hitlerism, the foetal religion presently aborning in Chile. He would like to drop by Santiago and have a chat, perhaps to “glean some intelligence from the gauchos.”

But it’s too late. No more time for the transoceanic jaunts that have varied his long life and kept boredom at bay. The Great Beast 666 happens to be on his death bed. Chapter One is over, and he dies.

Chapter Two begins as follows:

So, let’s sort this out, shall we?

In those seven words you have the essence of this particular historical figure: unkillable inquisitiveness, unshakable aplomb in the sort of psychic circumstances that drove so many of his apprentices and fellow magi insane. Of Crowley’s many fictionalizations, this novel gets best into his head. Erudite, prideful, lascivious, funniest man of his time, and the mightiest spiritual spelunker–he speaks and shouts from these pages as clearly as he did in his Autohagiography, which is paradoxical, given the irreal setting of Elmer Crowley: a katabasic nekyia.

Now that his mortal coil has been shuffled off, Crowley doesn’t know quite what to expect. He has mastered the world’s ancient funerary texts as thoroughly as anyone who ever lived, but fundamental questions remain. Will he be privileged to climb the sevenfold heavens promised by the Gnostics? Will his eyes be offered a luminous series of Tibetan liminalities, clear and smoke-colored?

Apparently not.

Something else materializes and looms up, rather more architectural. It appears the Egyptians came closer than anyone to getting it right.

Crowley’s ghost has been deposited in the Hall of the Divine Kings, as described in the Nilotic Book of the Dead. Of course, our hubristic Baphomet assumes that he’s about to be greeted as a peer by the immortal gods, “the soles of whose sandals are higher than ten thousand obelisks stacked end-to-end.”

But, no, they brush him off like a midge. He’s expected to supplicate like any run-of-the-mill dead person, to have his demerit counterpoised in the balance against a feather. Godhood denied, our high adept has been doomed to reenter the tedious cycle of rebirth. Injured pride, disappointed expectations, the prospect of boredom–these have never sat well with Thelema’s Prophet-Seer-Revelator. He’s about to start behaving badly. (A signal for us to stand well back and shield our eyes and ears.)

If he must return to the rigmarole of existence, it will be on his own terms. Exercising his prerogative as a magus of the highest accomplishment, Aleister Crowley will pick and choose his next carcass. He cold-shoulders the Divine Kings and calls forth Baubo, the headless Greek comedienne-demoness. Her job is to whisper filthy jokes to the peregrinating monad, to get it into a “meaty mood” before it gets stuffed, yet again, among female intestines.

April 11th, 2014 / 10:00 am

We All Sleep in the Same Room by Paul Rome

We All Sleep in the Same Room

We All Sleep in the Same Room

by Paul Rome

Rare Bird Books, November 2013

192 pages / $14 Buy from Amazon

In his debut novel, We All Sleep in the Same Room, Paul Rome achieves what even seasoned novelists often fail at: generating characters that feel real-to-life, situations that seem organic and natural, rather than the second-rate simulacra of bad fictions, and a cultivated style that is beautiful in its understated elegance — sculptural, even.

Much has been written lately on the ever-quickening Brooklyn lit scene, although there has probably never been a dearth of “Brooklyn novels” or “Brooklyn writers.” Rome’s first novel positions him as a new voice with an old soul, a writer more akin to Paul Auster both stylistically and thematically than to his peers, like Tao Lin and Adele Waldman, whose Taipei and The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P., respectively, chronicle the lives of young, writerly Brooklyners as they negotiate the perilous hinterlands of relationships — both to others and to the self. Rome echoes Auster in his clean, well-lighted prose, and Rome’s conjuries of the city, with its infinite chance happenings and endless sense of mystery, is likewise definitely Austerian. But whereas Lin and Waldman direct their foci towards the realm of listless twenty-somethings, Rome explores the vagaries and varieties of middle-age. Despite its being set in the Fall of 2005, Rome’s New York is the New York of old, and his subjects are similarly different than those of his contemporaries.

With surprisingly intimate psychological acumen, he dissects, scrutinizes, and mournfully portrays Tom’s and Raina’s failing (and ultimately failed) relationship. Tom is a union lawyer, a hard-working professional dedicated deeply to, and personally invested in, the ideals of justice and equality that his firm ostensibly seeks to uphold. Within the novel’s overall context of loss, the presence of an idealistic politics on the part of Tom makes the withering of it all feel especially concussive.

The novel is characterized by a powerful sense of the teleological: every absence-haunted sentence — each of them exercises in the potency of minimalism done right — seems to foreshadow intensely and evoke powerfully the fact that the novel will have a devastating and inevitable end-point. It seems so frequently to be raining or snowing in Rome’s New York. We All Sleep in the Same Room is a very melancholy work. We are drawn inexorably towards the emotional black hole at the novel’s core; we are sucked beyond its event horizon with every painfully wrong move on the part of Tom. Jessie, a young and incredible eager young woman and a recent hire at the firm, is at the heart of Tom’s and Raina’s marital divide — sort of. Rather than coming across as a “manic pixie dream girl,” a young woman who is, like the young women in some of Philip Roth’s novels, a tabula rasa upon which a disaffected and disenchanted older man can project his erotic obsessions onto, Jessie is truly “three-dimensional” and deeply human. Rome’s characters operate on a number of different registers, all of them faithfully drawn and vividly realized.

Rome’s style is lucid and elegant; he handles the issue of back-story — a pitfall for even the greatest of writers — with admirable élan. Like James Salter (Light Years, A Sport and a Pastime) and Richard Yates (A Special Providence, Revolutionary Road), Rome is interested in the internal, in the mysteries of selfhood, of past, of memory, and of regret. These he explores, like Salter and Yates before him, through the lens of a relationship dissolving and disintegrating as a result of the pressure put on the present by the protagonist’s past mistakes. And Rome’s authorial voice is astoundingly mature, his style effortlessly clean: lyrically restrained and “taut,” his prose reflects the mounting tension and anxiety that come to pervade the work as Tom’s domestic and professional life unravel. Rome’s narration exudes confidence and assurance, and has an ethos from the first line to the last — the kind of ethos that carries a novel and ultimately makes it one worth reading.

The novel is haunting and understated, with sublimated and shadowy pasts that re-emerge like phantoms. The persistence of past mistakes, the persistence of time, the inevitable forward-movement and forward-momentum towards the end of all good, or seemingly good, things: these are Rome’s real narrative interests, and he delves into them in thought-provoking and emotionally resonant ways. We All Sleep in the Same Room is a dirge for things lost, a New York novel of the old-school, and a powerful debut by a writer who has almost preternaturally insightful things to say about all that is.

***

Michael Abolafia lives in New York City. His writing has appeared in Sunlit, Supernatural Tales, the New York Daily News‘ online book blog, Page Views, and other venues.

April 7th, 2014 / 10:00 am

Conceptual Failure as Several Kinds of Success in Robert Fitterman’s Holocaust Museum

Holocaust Museum

Holocaust Museum

by Robert Fitterman

Counterpath Press, 2013

144 pages / $16 Buy from Counterpath or Amazon

In his book Notes on Conceptualisms, co-authored with Vanessa Place, Robert Fitterman states that “in much allegorical writing, the written word tends toward visual images, creating written images or objects, while in some highly mimetic (i.e., highly replicative) conceptual writings, the written word is the visual image.” He then says that “there is no aesthetic or ethical distinction between word and image” (Notes, 17). The reader tries (as a reader does) to make sense of this.

When a word is read or heard, its visual and sonic shapes activate the bodily memory of that word. This memory is connected to an image made up of a series of images (as all images are). There is no end to this series because it is by nature a series of series, infinitely referential. The “initial” series (the brain is so quick that we’re often completely unconscious of what images it is comprised of, or what we started off consciously thinking about) immediately births another series and this continues at a speed too fast for our fathoming, each series dropping out of another, until we hear or read the next word and the process starts all over again. This is brain vision (a written image), not visual vision (a visual image), and while the former is not any less vivid than the latter, there’s simply no denying that the two are, by nature, physically different experiences.

Fitterman is of course aware of this. But the goal of conceptual writing, as he later states, is failure (Notes, 22), and when a piece demonstrates the discrepancy between idea and execution—when what works in concept (for example, the written word being the visual image, rather than just referencing/conjuring it) reveals its artifice and deficiency in execution (the reader not experiencing the written word as, or in the same way as, the visual image)—it has been successful. In other words, the written word can, in highly mimetic writing, “be” (mimic, represent) the visual image within the writing (its conceptual framework), but it cannot literally recreate the experience of seeing (with one’s eyes) the visual image it is referencing. This is one of the reasons why Fitterman’s conceptual project, Holocaust Museum, is successful at what it does.

Holocaust Museum definitely qualifies as a “highly mimetic” or “highly replicative” conceptual work. The book is divided into seventeen sections—Propaganda, Family Photographs, Boycotts, Burning of Books, The Science of Race, Gypsies, Deportation, Concentration Camps, Uniforms, Shoes, Jewelry, Hair, Zyklon B Canisters, Gas Chambers, Mass Graves, American Soldiers, and Liberation—all of which are titles of actual exhibits at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.. Each section, accordingly, consists of captions that correspond to actual photographs (which are not shown, just cited by title) featured at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. The scenes described by the captions greatly vary in almost all senses—location, who or what (objects or people or a combination of the two) is pictured, action or lack of action, the level of brutality in such, implicit and explicit violence, etc.—but each caption explicitly relates back, in subject matter, to the title of the section in which it’s included.

In its most basic conceptual sense, Fitterman has made a Holocaust museum completely out of words. What makes this so is that the words are working exclusively as representations of images. What makes this work successful, in one sense (the conceptual sense), is that it fails by its very nature (as a piece of writing) to recreate the visual images its captions stand in for, as well as the inherently different experience of seeing a picture, rather than having it described to you. What makes this work successful in another sense is that the effect of reading the captions devoid of their photographs is incredibly haunting, and is so in a way that lacks familiarity to us (“We have seen the pictures of our past, but the point is the caption” – Vanessa Place, on Holocaust Museum). The language of the captions is sterile and simple, even in its depiction of absolute atrocity (“View of the door to the gas chamber at Dachau next to a large pile of uniforms. [Photograph # 31327],” Holocaust, page 61), and as witness to these depictions, the reader begins to, in a sense, read the language, the voice, as their own, feeling increasingly implicated as they move through the text.

With Holocaust Museum, Robert Fitterman has made a conceptual object that succeeds by his own standards of success (failure, specifically in its ability to replicate) as well as by a more mainstream literary standard—being evocative, haunting, innovative, and generally affective. This is one way for a work of art to be exceptional, and with its confrontation of an event as important, disturbing, and already-discussed as the Holocaust, Holocaust Museum proves itself to be a groundbreaking and extraordinary conceptual work from several angles.

***

Lily Duffy is a poet, teacher, and editor living in Denver while working on her MFA in poetry at the University of Colorado Boulder. Her writing has appeared in the Baltimore Sun, Baltimore City Paper, Hot Metal Bridge, ILK journal, Cloud Rodeo, Bone Bouquet, NAP, inter|rupture, and elsewhere. With Rachel Levy she co-edits DREGINALD.

March 31st, 2014 / 10:00 am