25 Points: Brushes With

Brushes With

Brushes With

by Kristina Marie Darling

BlazeVOX [books], 2013

50 pages / $16.00 buy from BlazeVOX or Amazon

1. This is Kristina Marie Darling’s 11th book of poetry; she is not even 30 years old yet.

2. Darling eschews traditional forms of poetry in favor of her own unique formal constraints: the use of footnotes, appendixes, images, definitions, bracketed verse, and erasure poetry. However, in Brushes With, Darling adds a new form to her repertoire: the narrative prose poem.

3. The collection begins: “We were no longer in love. The sky, too, was beginning to show its wear.” From this point forward, readers are plunged into many complex layers of the rubble of abandonment and loss.

4. The footnotes serve as historical commentary on the prose text. This makes for a matrix-like experience. We are reading a person’s intimate words, but we also know that this text has been abandoned, then found, then studied, then put on display. This technique makes the experience of reading the prose poems feel illicit in some way. We are peering into a labyrinth of secrets that are not meant for our eyes, yet are now uncomfortably preserved and public.

5. Even while reminiscing on the relationship before its end, the speaker foreshadows doom: “You told me there was dark matter I couldn’t see. That every star is a dead star.”

6. The imagery, like the one above, proves to be richly complex. All stars are dead; therefore, that which enchants us, that which we wish upon, that which we map out, gaze upon, pray to, is also doomed. In every romantic union, there is something dark that we don’t see coming, yet we should be aware that it’s there.

7. In “Feminism,” the speaker states: “I began to realize the significance of this gesture. What is love but a parade of memorable objects, a row of dead butterflies pinned under glass?” Ouch!

8. The speaker’s take on love is relentlessly jaded, yet she comes to sharp edged truths. What is love but our desire to possess, collect, admire. Yet, in doing so, we must sacrifice the subject’s life.

9. Footnote 18. ‘This statue of the Holy Mother would later be found headless in a tiny museum in northern France.” Once again, we have worship, mementoes, collection, ownership—all leading to destruction. Facelessness.

10. The marriage documented in the book unravels due to affairs. READ MORE >

August 20th, 2013 / 5:22 pm

25 Points: Room

Room

Room

by Emma Donoghue

Little, Brown, 2012

384 pages / $7.99 buy from Amazon

1. Not many authors could write believably from a child’s point of view and still provide such credibility and license to the narrator. That’s what you need to know most readily to begin this book.

2. Concepts like “TV People” and rain being nothing more than a blurry veil over Skylight–a saddening slap in the face realization for readers that this is really happening.

3. It is striking, the “savant” nature of the little boy – how he can be so well-educated with so few resources, and yet so ill-informed on social protocol and other “real world” mechanisms. It could be argued, though, that he is in many ways better off than a “normal” child.

4. This reviewer recommends reading this book aloud or obtaining an audio copy. Hearing the dialogue between the mother, the child, and Old Nick is especially gripping.

5. It is an incredible struggle not to be angry with Grandma. Grandma’s love for Ma exists but does not inspire.

6. The poem excerpt at the beginning. Yes.

7. The way the child refers to inanimate nouns as personified, proper-nouned entities provides reality to the voice of the child narrator, but also speaks to the attachment any human would have to inanimate things in a situation such as “Room” describes. It’s a very subtle way to calcify the experience for readers.

8. Page 67, “Princess Diana” “Should have worn her seat belt” — one of the funniest sidesteps in conversation throughout the novel, albeit cryptic.

9. The experience of the Indian family and their dog finding Jack in the park elicits severe, literal nausea. For the first time, picturing Jack outside of Room and experiencing what he must look like up next to other humans, other children – pure nausea.

10. There is a distinct failure to understand that radiates through the hospital. As such, the reader will experience a certain kind of rage and a certain kind of advocacy for Ma and Jack. On Donoghue’s merit, this is a great mechanism for roping readers in more tightly, On the other hand, the injustice provokes readers to consider how often and to what degree these situations are marred by “professionals” in our nonfiction world. READ MORE >

August 15th, 2013 / 12:06 pm

25 Points: Petrarchan

Petrarchan

Petrarchan

by Kristina Marie Darling

BlazeVOX [books], 2013

72 pages / $16.00 buy from BlazeVOX or Amazon

“Within every box, I found only compartment after compartment.”

1. Petrarchan is Kristina Marie Darling’s 8th book, published by the ever controversial Blaze Vox Books. (Yikes. Remember that whole thing? I still have love for the Vox, though.)

2. Much in the way she “took liberties with H. D.’s letters” in THE BODY IS A LITTLE GILDED CAGE, Darling uses ekphrasis, careful appropriation, erasure, and the work of Petrarch and Sappho (the latter, via Anne Carson’s translations) to achieve her grand illusion.

3. Kristina Marie Darling’s voice as a writer is unmistakable and unshaken regardless of mode or form. Of this, I am thoroughly convinced.

4. In fact, one thing that has repeatedly struck me about Kristina is how much larger in stature her writing voice is than its author. To be clear, this is not to reduce her as a person, but to exemplify her work as a force. Often, in an effort to amplify one’s voice over the din of modern media, the artist must become a personality first in order to gain potential interest in the work. Unfortunately, it becomes easy for the latter to suffer in the shadow of the former in the race. Darling reminds me that there is still a strong argument to be made as an artist for placing one’s ambitions squarely on the body of one’s art.

5. This is to say that I have no idea whose parties she attends, under which influences, et cetera, but I damn sure know when it’s her voice there on the page.

6. The reader will find in Petrarchan Darling’s familiar signature use of spare narrative and spectral imagery driving a carefully plotted course of marginalia and footnotes. To be fair, it is doubtful that anyone who is unconvinced or maybe even still undecided about her work in general will be swayed by Petrarchan. However, those of us who are believers or even simply interested parties will take comfort in knowing that what is gold still shines.

7. Tangentially, I have been thinking a lot about appropriation and erasure lately. As a writer who uses both at times almost criminally, I think a lot about what constitutes successful employment. After all, as some will invariably argue, can’t anyone do it? The short answer, of course, is yes. But to make a piece of erasure or other appropriation both successful and original despite its sources, I believe what the author chooses not to use, and why, becomes equal in importance to what is used, and how. The author must rely on the source text to some degree, but the artistic voice of the finished piece should stand on its own. Darling’s work—and Petrarchan is no exception—is as fine an example as any to underline these values.

8. I am thinking about corridors—hands and bricks or wood and the long-form sound of feet moving to some god knows where. I think about corridors a lot I think. I wonder if Kristina does too.

9. It is often easy to forget how the author implies a larger body of text with her use of marginalia as sparse narrative, set toward the bottom of the page, soaking up the white space of the specter it has picked apart.

10. Again, the ghostly presence hovering in the frame of the footnoted sections is largely the work of Francesco Petrarch, whose work I am largely unfamiliar with. I should really make it a point to change that. READ MORE >

August 13th, 2013 / 12:09 pm

25 Points: If You’re Lucky Is a Theory of Mine

If You’re Lucky Is a Theory of Mine

If You’re Lucky Is a Theory of Mine

by Matt Mauch

Trio House Press, 2013

100 pages / $16.00 buy from Trio House Press or Amazon

1. “If you can’t see it then you’ll just never know,” the subject said, “I wish I could talk in Technicolor”

-Prologue

In the seconds before Matt Mauch’s If You’re Lucky Is a Theory of Mine, the book recounts experiments done with LSD in Los Angeles, California during the 1950s. The above is said by a housewife, who recently swallowed a glass of water, to a doctor that couldn’t see the wavelets of colored sand the air was drawing into her cheek, the immediate refraction of everything at double pulse.

The two-parted-ness of the housewife’s (a tupperware-d figure often “lacking power”) comment to the doctor (a figure which harnesses a kind of intelligence / power to see “unseeable” systems at work within our bodies) is as tender as it is dismissive. Equal parts frustrated and othering and already imagining a reality beyond reality into reality.

You’ll never get it, the woman says to the exploding planet and the doctor standing just in front of it, BUT if I could talk differently, better, with a lot of energy that made you forget what love even is, maybe you would. She wants to be a piece of transmission more than she wants to be withholding.

2. “Is looking traditional? I want a new technology of perceiving.” -Bhanu Kapil

This is happening and collapsing and it is everyday. There is new teal, which is sometimes just the old teal with different teeth weeping out of a curvature of bone. I love all the filters and various containers we are pushing and plowing expression into. When I think of all the language, all the Internet, all the books, I see we have many throats to shoot through and grow new throats with. I love that, sometimes, I just look at a strawberry and almost go into a coma from amazement.*

*THEY ARE FRUIT COVERED IN A THOUSAND TINY SHIELDS.

3 & 4. In larger size letters on a different precursing page, Billy Bragg says, from the tinny roof of a song called “Busy Girl Buys Beauty,” some language that brushes against the opposite side of the room.

“What will you do when you wake up one morning

to find that god’s made you plain?”*

What if we don’t ever get to be that housewife, seeing what others can barely dream of seeing? What if we are a housewife in CPA’s clothing**?

We take drugs to rail against this, drink to rail against this, almost touch the lumps in the paintings at the museum, stick our heads in vents, stick our arms out the cow window, write these poems, fuck these poets, fuck these non-poets, drive through Utah, do blood rituals, etc.

*Google asks me, “DID YOU MEAN…What will you do when you wake up one morning to find that god’s made you Palin?”

**On the way home from the Greyhound station, a guy who introduces himself as an auditor at Wells Fargo, asks me out. A very small part of the many reasons I immediately say no has a sliver of something to do with this. I know, in a more messy way than a clean sentence can represent, I don’t believe I’m plain. It’s despicable in some way, this thought.

5. If You’re Lucky is a Theory of Mine delves into the tension and overlapping (the vibrating fearjoy ping ponging back and forth / froth) between these two things. Are you normal or are you a seer / a sear?

“On the way down the mountain

you understand what the seer sage

is saying: that honey-smooth will always taste

good to the tongues in our ears,

and balancing expertly on the miniature avalanches

beneath each of your downward-angled steps

will go unheralded unless

you herald it, which isn’t in your make-up”

-There is the hiding. Here is the seeking.

6. The book is hesitant to distinguish whether you or I (Is a poet the housewife or the doctor?) are more likely to fall into one category or the other. It often wryly suggests we are about one step away from either or. Or rather, it points out at the complex phenomenon that witnessing can be and is. On one hand, you experience the spectacular kind of texture that knowledge possesses when seeing something for the first time or when seeing something for what feels like the first time.

“Glacier says

to Sun, “Saw a sparrow trying to crack

open the husk of a cicada on a driveway.

Never thought to use a driveway as a tool

like that.”

-It’s one thing to want one’s life to be fulfilling,

another to want it to be very long.

Even a glacier can suddenly feel small in the face of how great smallness can be.

7. The central poem, “It’s a planet, we’ve an age,” the book oscillates around is embedded within a section called, NORMAL. The section and the poem mean to closely examine, over the course of thirteen pages, the dead body of how normal normal ever is. We know that NORMAL is relative, that our conceptions and opinions of what it is is always changing, that many people you know would be the last ones to call themselves NORMAL. I remember the first time I realized that everyone saw those little neon flecks of color on the inside of their eyelids whenever they stared at the sun.

“It’s a planet, we’ve an age,” begins with emphasizing distance, the human presence as galaxial pinprick.

“On the third planet from the sun

you smoke a cigarette, or a joint,

slowly”

8 & 9. As the poem progresses, the you dissolves and reforms as an I. An I filled with specific choices and unchoices made via the ancestral blood whipping his own blood around. Each time I close my thinning lids, those bright sun flecks make new and different patterns.

What was distant and giving off those road waves you see on hot highways morphs into:

Horses, Juanitas, Arnie, who was identical to other Catholic school boys his age until a “horse’s shoe cut itself in miniature / in Arnie’s cheek,” Cancer, my dad’s dad, my mother’s father, Bob Marley, Budweiser, Jackie and I and eight, eight eight, the mailman with the abortion knowledge, “the photos we take of each other,” Apartment D, “the sweaters we wear / collect hairs,”“Like paper towels / we try to keep a little bit of everything we touch.”

The thing which continues to remind us of our distance, of a contained and clumsy universality we potentially share, is the continual mention of “the third planet from the sun.” The biggest zoo.

10. Is this where the idea of chance enters (because chance has to enter as soon as you read that title)? LOOKS AT ARNIE. LOOKS AT THE THIRD PLANET WHERE SOMEHOW A CELL GOT UP AND DID SOMETHING. Is this where the idea happenstance person and happenstance language having real effects on the present whatever enters? READ MORE >

August 6th, 2013 / 12:11 pm

25 Points: Testicular Cancer

1. Germ cells are immortal.

2. Germ cells contain half the number of chromosomes needed to make an organism, and so are specially made for sexual reproduction, but they can divide and differentiate into any kind of biological tissue. They can even create complex organs made of multiple tissues.

3. A teratoma is a germ-cell tumor—a bunch of inappropriate tissue in some inconvenient spot on the body, replicating wantonly. The best teratomas (the ones with gory, romantic stuff like hair or teeth or—gasp—eyes!) are collectible, formaldehydable medical oddities.

4. Though they form prenatally, teratomas commonly become large enough to notice only much later. Some are detectable by prenatal ultrasound. Some develop so rapidly in the womb that they endanger the fetus.

5. Teratomas are benign in themselves but, for reasons not yet understood, occasionally undergo cancerous transformations.

6. Words that rhyme w/ teratoma: adenoma, carcinoma, granuloma, hematoma, melanoma, myeloma, Oklahoma, papilloma, tokonoma.

7. My teratoma swole my entire right ball w/ almost nothing but cartilage. When I first noticed it, it was the size of a peach pit. By the time I had a doctor look at it, it had grown to the size of a jumbo egg and it was hard as a rock. I didn’t know what a teratoma was when I dropped my pants so the urgent care doctor could get a good look.

“Jesus Christ!” she said. “It’s hard as a rock!”

The urgent care doctor wanted to know how long had it been like this. It had been like this a year and half. Well then, why was it suddenly such an emergency I had to come in here on a Saturday?

8. It could be a few things, she said. It could be cancer, which was unlikely; or it could be like four other things which I don’t remember—and which don’t matter now anyway ‘cuz it was cancer. (She never said the word teratoma, which is in hindsight like duh the only thing it could have been, right?) Whatever it was, I had to get an ultrasound immediately, and then go see a urologist.

9. If you pay in full at the time of your visit, it costs $100 to have your balls touched and screamed at by a real doctor.

10. The ultrasound technologist held a tube of ultrasound gel upside down over my human junk.

“When did you first notice a lump?”

“Like, a year ago.”

“And it’s some kind of emergency today?”

“Um, yeah. Uh, my wife…”

Schplorpk! READ MORE >

July 30th, 2013 / 1:24 pm

25 Points: VARIOUS SMALL BOOKS: Referencing Various Small Books by Ed Ruscha

VARIOUS SMALL BOOKS: Referencing Various Small Books by Ed Ruscha

VARIOUS SMALL BOOKS: Referencing Various Small Books by Ed Ruscha

Edited and compiled by Jeff Brouws, Wendy Burton, and Herman Zschiegner

Text by Phil Taylor, with an essay by Mark Rawlinson

MIT Press, 2013

288 pages / $39.95 buy from MIT Press or Amazon

1) “An evil word it is this love.” – Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones)

Perhaps the closest I’ve ever come to an original Ed Ruscha was working at the Graduate Theological Union (GTU) Library over in Berkeley up on the hill next to the University of California in 2002 or so. There was an art exhibit lasting several months of “religious art” or maybe it was “ideas of evil in art”… which included Ruscha’s one-word painting “Evil” (blood stains on satin) in its ever terrifically seducing red.

2) Or it may have actually been earlier than that, in the basement room at poet Tom Clark’s house in Berkeley on break from Poetics classes waiting for the bathroom. If, that is, it’s true that the tall horizontal painting of a semi-masked figure (some kind of postmodern Lone Ranger?) on one wall is in fact a Ruscha self-portrait. Which I hazily recollect being told by somebody sometime later on—or is it that it was a portrait of Ruscha done by Tom?

3) Regardless, my real introduction to Ruscha came via Jeffrey Karl Butler formerly of Portland, Oregon. Jeff once sent me a chair through the mail. An Eames-inspired piece. He knocked off the feet attaching various caps from an assortment of common household items in their place. The chair was sitting in my apartment vestibule beside the mailboxes when I came home from working at the GTU one day. Without packing or anything, a USPS shipping label smacked onto the front of the seatback, “LEGS” stenciled atop the back of the seatback, and under the seat stenciled “JKB ’01”.

4) “Fifty years ago, in 1962, Edward Ruscha published Twentysix Gasoline Stations, the first of a series of photobooks the artist made through the 1960s and 1970s. Consisting of black and white photographs of twenty-six filling stations situated along Route 66 between Los Angeles and Oklahoma, this deceptively simple book, much like Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917), irrevocably altered our understanding of art.”

– Mark Rawlinson

5) The gist of Various Small Books is to document every photobook “known as of May 31, 2012, with apologies for anything omitted” which one way or another continues, extends, or otherwise is in conversation with Ruscha.

6) A short text describing each photobook accompanies one or more photographs of the project. Many are also accompanied by a full two-page spread of images from out the photobook.

7) Photobooks are grouped in chronological order by year of publication: 1954-1987 (five projects), 1991-2000 (seven projects), 2002-2006 (twenty-two projects), 2007-2008 (nineteen projects), 2009 (fifteen projects), 2010 (seventeen projects), 2011 (five projects).

8) The first photobook presented is Ginza Kaiwai and Ginza Haccho by Shobachi Kimura and Yoshikazu Suzuki published in 1954. This boxed set of two volumes contains Ginza Kaiwai “an extensive history of the neighborhood of Ginza,” complete with photographs and maps, while “alongside this conventional book is a concertina volume, Ginza Haccho, with two parallel photographic panoramas of every building on the avenue Ginza 8-chrome between Shinbashi and Kurobashi bridges.” The impact of “a western influence” on this neighborhood is noticeable in the photographs and although it’s an open question whether Ruscha ever knew of “this remarkable predecessor” the possibilities are too enticing not to risk “anachronism or attributing influence where perhaps none existed.”

9) Ruscha’s Every Building on the Sunset Strip appeared thirteen years after Ginza Kaiwai and Ginza Haccho.

10) Some other photobooks likewise concerned with a specific strip of commercial or otherwise set of buildings: Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour’s Learning from Las Vegas, Robbert Flick’s Parade Route, Jean-Frédidéric Schnyder’s Zugerstrasse Baarerstrasse, Jonathan Monk’s None of the Buildings on the Sunset Strip, Edgar Arceneaux’s 107th Street Watts, Stan Douglas’ Every Building on 100 West Hastings, and Keith Wilson’s Every Building on Burnet (burn-it) Road. READ MORE >

July 25th, 2013 / 3:04 pm

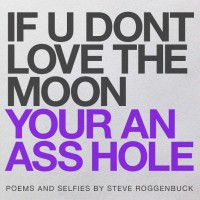

25 Points: if u dont love the moon your an ass hole

if u dont love the moon your an ass hole

if u dont love the moon your an ass hole

by Steve Roggenbuck

2013

$10.00 buy from LIVE MY LIEF

1. Burgeoning (burgeoned?) internet poet Steve Roggenbuck’s second book; promised to be meatier and denser than his first book, CRUNK JUICE.

2. CRUNK JUICE functioned well as a collection of Roggenbuck’s disparate subjects and styles–the startlingly direct and innocent love poems, the textual manipulation of “lowbrow” pop culture, the pseudo-immaturity blended with faux-irony–but each poetic mode was largely kept separate from the other via separate sections and poems, often punctuated by pages of isolated one-liners.

3. if u dont love the moon your an ass hole, on the other hand, stitches these voices together right down at the line level.

4. The most common type of poem in IUDLTMYAAH is a justified block of title-less text that reads like a transcription of one of Roggenbuck’s videos: line after line of relentless juxtapositions, jumping from something clever to something life-affirming to something brazenly obnoxious.

5. Example: “in spain they love football so much they even call soccer football. im becoming aware of the fact that boredom and laziness are social norms, that ive felt pressured to supress my excitement and set lazier goals. I TRAINED MY SON TO EAT OUT OF MY HAND SINCE HE WAS A TODDLER. IT’S RLY STARTING TO FUCK WITH HIM NOW HE’S 15.” And so on.

6. This sporadic format is a double-edged sword, and the amount of enjoyment you get out of this collection will largely come down to how much enjoyment you get from these individual lines. As one might imagine, reading a book full of these–even with variation–might be nonplussing to many.

7. One thought I had was that this book might not be ideal for reading in one go, though, and might be better suited to short reading bursts. Its small size is ideal for this: put it in your pocket/purse and bust it out for little boosts throughout your day.

8. These poems read like little peeks at a singular, alien twitter feed. You get a few esoteric jokes, an inspirational retweet here, a cryptic typo-ridden observation there. IUDLTMYAAH accurately recreates the rhythms and tempos of internet browsing, with random, potent bits of information all jammed up with one another, each clamoring for your fleeting attention with a hyperbolic, exaggerated language/voice.

9. “ok if jesus come back I will teach him Internet. ‘bad writing’ is a meaningless phrase that creates hierarchy where its not apropriate. EMO DAD license plate. buddha buddha buddha buddha rockin everywhere. i peaked out the window before bed and saw a brown buny hoppin across the snowy yard.”

10. I hate to say something like “ADD-addled” and make some damning generalization about a generation’s attention span due to the internet or whatever but yeah… I think I just did anyway. READ MORE >

July 23rd, 2013 / 12:09 pm

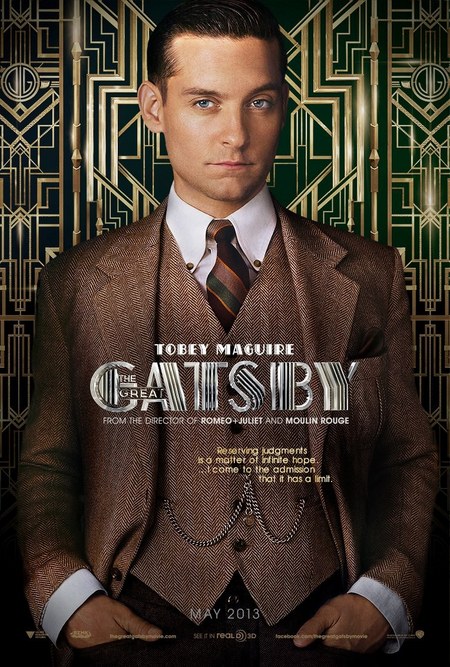

25 Points: The Great Gatsby Novel, Game, and Movie

1. “In my younger and more vulnerable years,” Nick Carraway from The Great Gatsby starts. The first part of the book revolves around the question, who is Gatsby? But what I always wondered was, who exactly is Nick Carraway?

2. As to the question of Gatsby, I find it interesting that there are so many similarities between Jay Gatsby from The Great Gatsby and Don Draper from Mad Men. Both went to war as poor men without any real place in the world. Both came up with different identities to hide their past. Both fell in love with beautiful women. The main difference was Don got the woman he chased after and became miserable. Gatsby died for a love that didn’t love him all that much and became a symbol of the Lost Generations of the 1920s.

3. F. Scott Fitzgerald also worked at an ad agency during the early part of his career. What would a Mad Men episode written by Fitzgerald have been like?

4. Fitzgerald wrote The Great Gatsby after the failure of his play, The Vegetable. He was deeply in debt and an alcoholic. He hoped Gatsby would become a success. It received mixed reviews and undersold at 20,000 copies when he had hoped for at least 75,000. In modern film terms, it was a box office disappointment. Some critics have suggested a novel about affluence in a time of economic depression would have been less than palatable for readers. By the time Fitzgerald died, The Great Gatsby had sold a total of 25,000 copies. He died believing he was a failure.

5. Bahz Lurhmann’s The Great Gatsby exceeded sales expectations at the box office, bringing in $51.1 million dollars starring millionaires acting as millionaires. READ MORE >

July 16th, 2013 / 12:21 pm

25 Points: Burial

Burial

Burial

by Claire Donato

Tarpaulin Sky Press, 2013

104 pages / $14.00 buy from Tarpaulin Sky

1. For reasons both Biblical and practical, we must “let go the dead.” But “persons never completely let go the dead.”

2. The main characters of Donato’s debut never leave the side of the dead. Father, dead, belongs here. The unnamed woman is describing as checking-in to the morgue. She’s there to stay, also, for a while.

3. Burial is concerned with the strangeness of death, something lost in its ubiquity, until we see it close. At another funeral near the start of the book, the congregation is described as “yawning, unable to recognize the weight of the ghost.” Mouths open, they might as well have been singing.

4. Donato’s heavy usage of commas, in the vein of Peter Markus (We Make Mud) and William Gass (“The Pedersen Kid”) before her, is almost a way of stalling all death.

5. Father is dead. His capitalized self stands like a tree amongst the brush of other words.

6. “Father was a man. He taught lessons in his language, and also raised his voice. ‘A lovely day to go fishing,’ he said. ‘The water is frozen,’ he said. Then he drowned in the lake.”

7. Burial is a grief-dream, an attempt to un-sew pain from experience and to reveal it in language.

8. “Mind’s a confused, tangled skein.” Particularly when it is pulled by pain.

9. “And the doe—the poor, female doe—collapsed at the scene. Two cracks rang out. He shot her. He shot her dead. ‘A lovely day to go fishing,’ he said, yet before he could indulge in his reward—field dress the damn deer and pay tribute to his success, his all-time best, grand aptitude for chase—he drowned in the lake.” Father’s final moments return, as grief does, often in different permutations. What’s the point of language if it can’t unmake and remake?

10. There is the woman, and Father, and Groundskeeper, who “kneels beside her bright yellow bucket,” and is the keeper and cleaner of these dead. READ MORE >

July 11th, 2013 / 12:09 pm

25 Points on Ideisms: Beginnings Toward the Poetics of Always After

Being a Review of Notes

on Conceptualisms

by Robert Fitterman and Vanessa Place

Notes on Conceptualisms

by Robert Fitterman and Vanessa Place

Ugly Duckling Presse, 2009

80 pages / $10 buy from UDP

As it is high time that our growing faction of Ideists had a manifesto around which they could unite, we, that is, Joel Kopplin and Kurt Milberger, humbly offer these notes toward a report of the history and conceptions of Ideisms with particular emphasis on the practice’s aesthetics, specifically poems.

1) The poetry of Ideism: the hangnail that breeds, that bleeds when finally plucked.

2) Books are bound to remain unread because to really read is a kind of rape.

3) Ideism thinks through houses, beyond their walls and windows, and out into the atmosphere where it burns as falling space junk.

4) Ideism is the eternal window out, the rhombus artfully set before venetian blinds, condensed so as to see the street below to approach the equation: what, finally, is next?

5) The permutations of the phrase reveal the poetics of Ideism. Id-e-ism. I-deism. Id-eism. The symbol multivocates, illuminates, and refuses to condense its referent.

6) Ideist poetry reconstructs new acronyms which compress and describe discourse-specific speak: philistines and neophytes fall down and weep with shame upon the altar of each letter of the new word. READ MORE >

July 2nd, 2013 / 1:08 pm