25 Points: Wish I Was Here

1. I cannot explain how excited I was to see this film. I watched Garden State and listened through the new soundtrack to prepare for, what I figured was going to be, an emotional experience.

2. The opening monologue was a little unnecessary. (I think he says the same damn thing, like, three times throughout the whole film.)

3. Zach Braff must be one of those “California Dads” who yell obscenities in front of their children, smoke weed in the drop off lane in front their kid’s school, is an unemployed “artist,” and is constantly having an existential crisis.

4. Zach Braff seems uncomfortable with being Jewish.

5. Things I didn’t expect to see in this film: Zach Braff masturbating.

6. This is the most attractive I’ve ever seen Kate Hudson.

7. Thought it was cool when I realized that Zach Braff’s son, Tucker, (played by Pierce Gagnon) is the “Rainmaker” from Looper. (How the hell did he get into this movie?)

8. Zach Braff clearly has daddy issues. (See Garden State for further evidence.)

9. Can’t believe Zach Braff doesn’t at least have a part-time job or something. His father pays for his children’s schooling, his wife brings home the bacon, and I guess Braff just sits there and studies his lines all day.

10. What I learned from this film: God doesn’t care about your dreams.

September 4th, 2014 / 2:26 pm

25 Points: On the Road

|

On the Road

by Jack Kerouac

Penguin, 1999

304 pages / $17.00 buy from Amazon

|

1. First thing I read by Kerouac was On the Road.

2. After that I read Dharma Bums, Big Sur, Mexico City Blues and a lot of other Beat shit (the most obscure of which was this poet Bob Kaufman who didn’t write his poems but walked up to ppl in cars at stop lights and spouted them then and there. After JFK died he went into a 10 year silence. When it ended the first words he spoke were: “To all those ships that never sailed” and then some more. I got that quote transcribed on my iPod. The iPod broke last summer.)

3. Big Sur is my favorite. The last few lines – that turn, that blink – I want it to be true and I think it is.

4. I first read On the Road my junior year in high school. It was just what I needed. I was bored. I called it depression at the time, but really I was just bored. I wanted to get my kicks.

5. When I got to college and read more “literature,” I grew wary of my early infatuation with the Beats. It seemed juvenile. I was eager to reread so I could dismiss it.

6. Then I reread it my junior year in college and I still liked it.

7. Dean is a crazy motherfucker.

8. I want to “sweat” like Dean. Of all the words I got from Kerouac (“blow,” “ball that jack,” “kicks”) I think sweat is my favorite. Dean gets going a hundred miles an hour just sitting there talking, scheming, licking his lips.

9. I’m not sweating. When I do sweat I don’t sweat for the reason Dean sweats. I sweat because its hot out or I’m nervous.

10. On the Road is very much of its moment: cars, San Francisco, the attempt to lay naked the psyche.

September 2nd, 2014 / 1:15 pm

Mr. Mercedes by Stephen King

Mr. Mercedes

Mr. Mercedes

by Stephen King

Scribner, June 2014

448 pages / $30 Buy from Amazon

Like many writers my age (31), I probably wouldn’t be one if it weren’t for Stephen King. At 16, finding the idea of short story writing woefully unambitious, my early attempts at novels were thinly-masked Stephen King impersonations. Based on the malodorous work that turns up in self-publishing, writers’ workshops, and slush piles, I’m not alone in that my first fictional efforts reeked of The King.

His influence isn’t necessarily a bad one. King became a best-selling author thanks to his expert pacing, gift for metaphor, wry sense of humour, and a number of intangible talents. Adam Ross and Justin Cronin are recent devotees who demonstrate that even elite ‘literary’ writers can benefit (both financially and creatively) when they borrow from King’s bag of tricks.

The most important way that King aided in my development is that his work has always been littered with literary and cultural references. (In recent years, he’s been obsessed with Philip Roth, comparing the reception of his own work to Roth’s in essays, and frequently bringing him up in fiction.) In this way, King inadvertently sabotaged my love for him. He’d reference Jack Kerouac or Norman Mailer, and their writing would end up on the bookshelf in my childhood bedroom. With all those major works waiting to be read, I found myself in a situation described by Arthur Conan Doyle in The Magic Window, a short volume that celebrates the contents of his book collection.

“It is a great thing to start life with a small number of really good books which are your very own. You may not appreciate them at first. You may pine for your novel of crude and unadulterated adventure. You may, and will, give it the preference when you can. But the dull days come, and the rainy days come, and always you are driven to fill up the chinks of your reading with the worthy books which wait so patiently for your notice. And then suddenly, on a day which marks an epoch in your life, you understand the difference. You see, like a flash, how the one stands for nothing, and the other for literature. From that day onwards you may return to your crudities, but at least you do so with some standard of comparison in your mind. You can never be the same as you were before.”

September 1st, 2014 / 10:00 am

You’ll Know When I’m Talking to You: A Review of Michael Earl Craig’s Talkativeness

Talkativeness

Talkativeness

by Michael Earl Craig

Wave Books, April 2014

104 pages / Buy from Wave Books or Amazon

Without relying on the word “reticence” to describe the work, I would have to say that the poems throughout the collection feel withdrawn, taciturn, almost. Lurking in each one, though, is a sense of something boiling, some untapped resource, and these poems, these are the spill-over that the speaker couldn’t keep from bubbling out, like pasta water before you put the wooden spoon on the pot to keep everything calm.

The poems have in them and around them the sense of a Williamsonian take on “no idea but in things,” but they sound and read like early Williams, not Patterson Williams. The problem, if we can call this a problem, which I do not necessarily think it is, comes from how the music of the poems appear. Because the poet chooses to state the thing and not the idea, not the flourish or the afterthought, the thing itself yields only what it can yield:

I wear a light brown suit.

When I come upon you I grope you

for what seems like ten minutes.

As you have noticed.

— from “Sleepwalking through the Mekong”

and

struggling with his bags puts

his ass against my head for what

(corduroys) feels like a full

minute.

— from “What Will I Call This Poem”

Two things to note, here: first thing is that, because of his reliance on the pedestrian language, on the language of the thing and the action itself, it requires a certain precision, a boldness, even, to not inflate the action or the thing, but let the thing and the action remain what they are. This isn’t a poet hiding behind his pen. This is a poet incredibly stark and revealed to us, which allows the second realization to occur: He’s funny. That small twist of, “As you have noticed,” sounds remarkably like the joke in “This Is Just To Say,” that, yes, she probably noticed the ten minute night-groping session. Same goes for the parenthetical “(corduroys),” because it’s placed exactly where it should occur to make the joke work.

When you’re working with the onliness (to invent a word) of the thing and the action, it requires great skill to know how to place it where it should belong, to actually get more out of it than what it seems to present.

August 29th, 2014 / 10:00 am

25 Points: Boyhood

1. Boyhood resists most attempts to analyze it outside the circumstances of its creation. Richard Linklater has filmed a group of actors every year or so for more than a decade, collecting episodes that tell the story of a young boy, Mason (Ellar Coltrane), and his family. The success (and the complications) of this approach and the events depicted on-screen compete for our attention, inasmuch as we can separate them. There’s no easy engaging with Boyhood purely on the level of plot and character.

2. Linklater’s experiment gives him creative latitude with the coming-of-age story that storytellers don’t always have (or don’t always grant themselves). Mason’s mom (Patricia Arquette) marries and divorces an alcoholic, then marries and divorces an alcoholic once again. In another film, this instance of repetition might play as laziness on the part of the filmmaker; in Boyhood, it plays as a function of the film’s verisimilitude. (‘That kind of thing happens in real life,’ etc.)

3. Boyhood also complicates the manner in which a viewer distinguishes a performer from his or her character, especially in the case of the film’s child actors. We are seeing these people grow up—quite literally, if only to a point. This is unsettling at times, seeing the continued physical development of a person without having any insight into his or her actual life. And Boyhood is much better at persuading us to invest in what’s on-screen than the latest item on your Facebook newsfeed about a distant cousin’s kids.

4. Between Boyhood’s documentation of the year-by-year aging of its young actors and the film’s general verisimilitude, Linklater’s decision to preserve—on film—Ellar Coltrane’s unfortunate late-teens facial hair is at once cruel and perfectly appropriate.

5. The choice also demonstrates the perils of verisimilitude. We don’t often see facial hair this ugly in cinema; underdeveloped in a manner that makes it also appear somehow unclean, a manner that communicates its own basic misguidedness. Although Coltrane’s wispy attempted goatee makes contextual sense, it also registers (perhaps too intensely) as an aberration.

6. Boyhood really only becomes a film about boyhood after an hour or so. Until that point, the film’s attention belongs to Mason’s family as a unit. Of course, many young children spend more time with their siblings and/or parents than older children do. But I missed the focus on Mason’s larger family once it was gone. A curious viewer might wonder when and how Linklater decided on the boy as his subject, when he decided on his film’s title, etc.—again, even matters of plot will likely lead the curious viewer back to thinking about the film’s production. The conceit is inescapable.

7. A curious viewer might also wonder if Linklater merely felt more comfortable telling the story of a young, male aspiring artist than he did telling a more holistic family story—or if he worried that audiences wouldn’t turn out in the same numbers for a similar movie about a young girl.

8. Patricia Arquette in particular has an arc that’s an arc as legible as Mason’s and arguably more compelling. Linklater never abandons Arquette’s character as she navigates higher education and single motherhood, but it’s a real sadness that the movie becomes more conventional in its focus as it goes on. We can see other films within this one, and that sense of possibility is bittersweet.

9. Though in fairness to Linklater, if one looks at the range of films he has made while not attending to Boyhood—the Bad News Bears remake, A Scanner Darkly, Bernie, Before Midnight—then the narrative coherence and tonal consistency of Boyhood is remarkable, whether or not the film becomes another story of a young white dude finding himself.

10. Mason’s father (Ethan Hawke), a wannabe musician, comes and goes during the first years of Mason’s life we see onscreen. He’s a consistently inconsistent presence, someone whose life as an artist has not gone as planned—which makes his scenes valuable counterweights to later scenes of Mason discovering his own artistic ambitions.

August 28th, 2014 / 2:17 pm

25 Points: Black Cloud

|

Black Cloud

by Juliet Escoria

Civil Coping Mechanisms, 2014

144 pages / $13.95 buy from Amazon

|

1. For some reason, I find this book really blackly funny sometimes. Maybe this is a strange reaction, I don’t know. More on this later.

2. Some of it is a bit like those bits in Breaking Bad where Jesse ‘falls of the wagon’ and goes back to taking drug and his house reflects it. I thought those bits in Breaking Bad were ok so this is a compliment.

3. This makes me think about something that may be culturally different between drug cultures in the US and drug cultures in the UK. In the UK, apart from in the eyes of the tabloid media, the law, etc., pretty much all drugs such as amphetamines, MDMA, weed, coke, acid, even, are all pretty much seen as sort of fairly clean-living party drugs and only heroin and, probably, crack are sites of visceral misery-literature style affairs, sites of crack-dens, heroin hangouts etc. The party drugs are just fine and clean-living things to anyone initiated into them with no sort of self-hatred or self-development or depression surrounding them necessarily because that’s reserved just for heroin and crack alone in the UK. This is my experience anyway but maybe everyone else in the UK would disagree. It just makes me wonder about the cultural differences as far as drugs are concerned and this book is a great example of that. Why not be honest about a common drug culture in US literature as this book and most Alt-Lit does, it screws up all those ‘wholesome’ Christian-Right bullshit images of religious-corporate America so that’s a good thing.

4. A point related to this. 12-step therapy seems different here in the UK compared to the US but also pretty similar. I like to feel these cultural differences.

5. Points 3 and 4 are maybe a thing for Alt-Lit more generally rather just this book but this book does do a good job of exemplifying something that I’ve been trying (and probably failing to articulate) and how wrong I was. More on this later.

6. “Therapists have looked at me, their eyes pleadingly wet and round, and said that growing up in a household like mine must have not felt that strange because it was all I knew. I can’t say this was true for me, not quite, because I do remember the pliancy of things, how nothing ever felt like it was happening at the right time or would stay standing up”. This is one of my favourite lines in the book because it’s also happened to me, as I grew up in a similar situation as the character in this story/author (the membrane is thin in this book, I’m guessing) and it feels true and I know it to be true and what more can you want sometimes from fiction if not some kind of truth?

7. The films that accompany this book are fucking ace by the way. Search them out on Vimeo. They’re some of the best films I’ve seen accompanying a book. I like films that accompany books. These are quite Lynchian at times and other times like a Kate Bush video somehow.

8. “Then my mother took me across the hall, closed the door, turned on the record player, Jane’s Addiction (I still hate that band)…” This is my second favourite, no my equal favourite, line in the book (from the same story – maybe I’m biased, maybe it’s why I said I found quite a bit of this blackly funny?) again because it is so true. I must be older than Julia because mine was Bob Dylan and Neil Young both of which I like now, wounds heal occasionally or sometimes you realise that it was just two contexts mixing up in an unfortunate way. Childhood memories are like this (good or bad ones, although in reality they’re always mixed) and she captures it beautifully and economically in that simple Jane’s Addiction detail. I’ll vote for this book all day on the strength of that detail.

9. This entire book isn’t blackly funny to me, by the way. Although, I wasn’t being flip when I said that, some of it is (but maybe I’m biased towards it). It couldn’t be blackly funny throughout to anybody. Some things are very sad in it, occasionally brutal. The ambivalence of life is herein. It oscillates at times, like most of, like some of, life does between extreme visceral misery and extreme visceral joy.

10. If you want poetry, consider the comparison between the two images of a mother on page 57 — one where she is modelling in a magazine and the other where she is “dirty and buzzing in the bright morning light” READ MORE >

August 26th, 2014 / 1:24 pm

Easy To Get Here, Hard to Leave

Forest of Fortune

Forest of Fortune

by Jim Ruland

Tyrus Books, July 2014

288 pages / $24.99 Buy from Amazon

In his 1998 documentary Advertising and the End of the World, Sut Jhally defines culture as the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves. He further points out that the primary storytellers in our culture—the ones who have the most prominent voice in articulating our value and belief systems—are advertisers. It’s an elegant point, so seemingly simple that its depth can be lost without a few moments to meditate on it.

Most discussions of advertising itself in our culture are limited to the question, “Did that particular advertisement inspire me to purchase that particular commodity?” It’s a feckless question. Jhally notes that the answer to it may be relevant for the people selling the commodity, but it has little relevance to everyone else. Instead, we should be asking ourselves, “What’s the deep-seeded impact of the overwhelming wave of advertising that crashes on us every day?”

What we, as readers and/or writers of novels, don’t discuss much is the relationship of our medium to advertising. Novels are the one contemporary media that is not and can not be saturated with ads. (At least that’s true for the paper ones.) This is one of the reasons I read so many novels. This also leads to one of the great challenges for novelists: to wedge their little story into a culture besieged by several thousand daily advertisements.

Jim Ruland’s recent novel Forest of Fortune is one of those little stories consciously wedging itself into the conversation about advertising. It treads upon similar ground as Jhally’s documentary, yet does so in a tone that allows the reader a bit more freedom in her interpretations. Jhally’s tone is clear from it’s very title: Advertising and the End of the World. Nothing spells doom like that. Ruland also demonstrates his approach early, but in a much more subtle fashion. One of his protagonists, Pemberton, checks into a rundown motel with weekly and monthly rates below the forty-dollar nightly rate. The clerk gives him a sales pitch about one of the rooms. Pemberton is hyper-aware of what’s going on. “A copywriter by trade, [he] knew brochure copy when he heard it, yet was seduced all the same.”

Again, it’s a simple, elegant way of introducing a deep point. Pemberton’s reaction matches a very common one in our culture. We’re often seduced by advertising, untroubled by the knowledge that we’re being lied to, uncritical of the alternate reality it sells. We want the story regardless. In almost every case, it’s the story we purchase. The commodity is just the bi-product, something we’ll keep around until the story loses its luster.

The setting of novel further illustrates this relationship with advertising and consumer commodity culture. It takes place in a fictional California town called Falls City. The name is probably more literary play then heavy handed symbolism. Pemberton arrives there and thinks, “False City, indeed.” It’s a fun way of sending a reader away from the falsity promised by the more specific setting of the novel, Falls City’s Thunderclap Casino.

August 25th, 2014 / 10:00 am

Working On My Shit: The Art of Distraction

I’m currently working on my novel. I’m also currently working on dying my hair the perfect shade of cornflower blue. I’m also currently working on trying to find just exactly where the hole is in my air mattress as it slowly deflates beneath me.Lately I have found the process of “working” far more interesting than the work itself. According to the ear-worm currently inhabiting my brain–better known as Iggy Azalea– the word I’m looking for is perhaps better known as “the struggle” or “the hustle,” as she so eloquently states in her radio hit “Work.” Put in pretentious art world terms, perhaps I’m also referring to “the process.” But really, I’m talking about the cracks in the sidewalk on the path to the end result. Procrastination. Distraction.

Somewhere between the initial conception of an idea and the completion of the project exists a murky abyss of abstraction in which the horizon line is hidden–or may not even exist. It’s a slice of creation in which anything is possible and everything seems impossible.

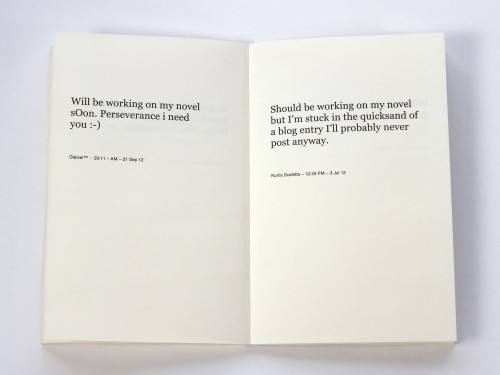

There’s someone else now that seems to share my interest in the spaces in between when a work is imagined and finished: Cory Arcangel. Arcangel has recently published a book titled Working It’s a physical book containing a plethora of tweets written by people working on their own novels. Tweets include “#Offline, working on my novel! =) Be back later!” and “A bottle of red, a hot bath, and working on my novel until my man gets off work. Sounds like a fantastic start to the holiday. :)” The book is bursting at the seams with naiveté, which can be off-putting at times–but behind that naiveté is the glimmers of hope that seem to motivate even the most jaded and misanthropic to write.

Reviewing Working On My Novel for the Paris Review’s blog, Dan Piepenbring has a different take on the book: “a sad monument to distraction.” But what exactly is wrong with distraction? I think perhaps, Working On My Novel, despite being slightly more gimmicky than clever when translated from twitter into a physical book, is an ode to the in between period of creation. It’s about the process of trying. It’s about the process of failing in one direction, yet forging onwards in another. Hash tags and typed smiling faces may be annoying as hell, but Arcangel has a point: Working On My Novel is about “exploring the extremes of making art, from satisfaction and even euphoria to those days or nights when nothing will come, it’s the story of what it means to be a creative person and why we keep on trying.”

Imaginary Portraits by Joshua Ware

Imaginary Portraits

Imaginary Portraits

by Joshua Ware

Greying Ghost, 2013

Limited Edition / Chapbook Page

My thumb surfs Instagram. I sit at my desk to write this. I am constantly distracted by a false reality. There are people I know there. They are eating tacos, taking pictures of sunsets, their partner stares out from a small screen I hold in my palm, I press like to let them know I see them. There is no way to escape our new duality, but I think it helps to be aware of this reality. Here is the problem: what is real or more real. How do we classify reality & does this change through location, movement, isolation. Joshua Ware introduces me to a world I know well. Here it is winter. I am wearing a hat. I am looking at myself as reflection. I am not sure it is really me.

A small blue book / It fits well in my hands. Small poems / Coy, they coax & murmur / I know you / the shape of darkness

You are dressed for winter, a chill in the air. Waiting. What forms do we take when met with a lens? How do we become a recreation/abstraction? How are we changed?

You sit atop a gray river / side rock, as water rush / swallows your voice, drowning you / by volume. The poet relocates to a new city. A traveling between two regions. Wind gusts through our private stillness. We are always somewhere. There is a struggle in always knowing where you are. Is it supposed to make you different? Should we expect change? Your muted / mouth opens a space for / poetry

Hello, avoidance. The escape plan proposal is returned, rejected. I sit at my desk with coffee. It is cold now. I feel this speaking to some part of me. No matter how surrounded I am there is loneliness in my body.

IMAGINARY PORTRAIT

In an otherwise darkened room

computer-light illuminates the contours of

your face, mimicking the neon shine of

an interstate motel sign that burns

through cornfield and prairie grass

somewhere in Middle America, as you drift

into a reverie of body parts, hoping to avoid looking at

yourself while you look at yourself

in a mirror. But your reflection

returns to you always in words

and the charred remains of cornstalks.

August 18th, 2014 / 10:00 am

A THEATRICAL ESSAY ON TRANSFORMATIVE THEATER FROM THE WORKS OF A FEW CONTEMPORARY FEM WRITERS

The second e-version of Gurlesque, an anthology of “the new grrly, grotesque, burlesque poetics,” is coming out soon with an expanded number of amazing female writers, including Jennifer Tamayo, Marisa Crawford, K. Lorraine Graham, Kate Durbin, Kate Degentesh, among others— along with the original contributors, one of whom is Stacy Doris.

When I read Doris’ funny, edgy, cerebral, and (dis)sensual Paramour in college, I knew I needed to go to San Francisco State for my MFA so that I could work with her in person. Stacy proved to not only be a phenomenal writer but also a caring mentor. Her passing in 2012 still feels raw today.

After reading an excerpt of Doris’ book The Cake Part [1] which was published in the first edition of Gurlesque, I decided to read the full version and then (circuitously) write the following essay, incorporating other writers that used theater the way she did (or did not) in that book.

Only, since I was writing about transformative theater, I figured the traditional essay format wouldn’t lend itself as well as a more dramatic format…

***

Scene: In a spaceship in a parallel universe. Android GERALDINE KIM types commands into the complicated lit-up dashboard as her ship is being attacked by a multitudinous tentacled alien race.

GERALDINE KIM: (ignores cosmic blasts while typing furiously.) I tried to write an essay on theatrical writing (not to be confused with the genre but more a leitmotif within other genres of writing—namely poetry) and then I realized that there are actually only a handful of instances of this in contemporary fem writing (that I could find).

GERALDINE KIM’s BEST FRIEND WHO WISHES NOT TO BE IDENTIFIED: (enters.) How many instances did you find?

GERALDINE KIM: Four.

August 15th, 2014 / 10:00 am