Written on the Body

Written on the Body

by Jeanette Winterson

Vintage, February 1994

192 pages / $14.95 Buy from Amazon

&

To the Wonder

Dir. Terrence Malick

2012

I

To put it another way

I would give all metaphors

in return for one word

drawn out of my breast like a rib

for one word

contained within the boundaries

of my skin

but apparently this is not possible

and just to say – I love

I run around like mad

picking up handfuls of birds

– Zbigniew Herbert “I Would Like To Describe”

The greatest irony for a writer, a person obsessed with language is to run into the boundaries of words. In our intense, overwhelming moments these faithful friends fail us when we need them most. All artists seek to express something, but what do you do at the end of expression?

That we call the ineffable the “ineffable” points to the paucity of our expressive capabilities. This is both a universal and a poignant contemporary problem. Post-modernity, while often exaggerated, highlighted the strange duality of living in a world constructed by words and the attending inability to transcend the world of words. From time immemorial artists understood the inability to translate the wondrous into a chain of letters and symbols, but with the accretion of time the problem of clichés grew, leaving many to shrug in cynicism at our inability to say anything new or urgent.

II

“Love demands expression. It will not stay still, stay silent, be good, be modest, be seen and not heard, no. It will break out in tongues of praise, the high note that smashes the glass and spills the liquid.”

– Jeanette Winterson, Written on the Body

It would be the greatest torture, if love really could contain such a self-contradiction, for love to require itself to keep hidden, to require its own unrecognizability.

– Soren Kierkegaard, Works of Love.

No topic has seemed to run its course more than our abiding obsession with love. We like to think of this obsession as timeless. We recall Shakespeare’s sonnets, and the urgings of Jesus, but love rarely engendered this kind of devotion as it does in our time. In an increasingly secular and secularized world, Love has become our universal religion, our God, the altar at which we pray. It provides the foundational meaning of our lives and defines our pursuits. In our zeal and haste we’ve plundered the emotion, the experience, the concept leaving it bloodied, bruised, depleted. No sentence has more fill-ins than the sentence Love is_________.

Yet, as Winterson writes eloquently, love does demand expression. An unexpressed love is hidden, narcissistic, predatory, and painful. In the same breath Winterson writes, “It’s the clichés that cause the trouble.” There is no greater cliché than “I love you” and yet, there is nothing that needs expression more than love.

A sort of artistic paradox.

Clichés about love not only threaten the ability to express our deepest emotions and thoughts, but force us to experience love in the shadows of other people’s conception.

Do you fall into love, or create it? Does love grow or wither, does it overtake your life? Does it matter?

The Big Smoke

The Big Smoke

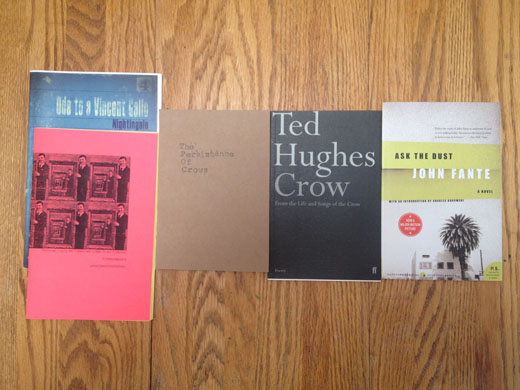

Fun Camp

Fun Camp Tampa

Tampa Antiphonal Airs

Antiphonal Airs Written on the Body

Written on the Body The Natural Dissolution of Fleeting-Improvised Men

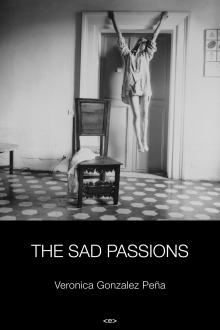

The Natural Dissolution of Fleeting-Improvised Men The Sad Passions

The Sad Passions