Behind the Scenes

EMBRACING POWERLESSNESS IN DEFINING ART : THE LEGACY OF ENTARTETE KUNST (1937)

The Stayin Alive of the Gallery Show-An IRL Victory

The insightful and highly regarded art-critic Jerry Saltz recently wrote an ambiguously polemical essay in which he crywolfed the death of gallery shows1. The primary theme of his argument is linked to the Internet’s takeover of the sales departments and the URL-manner in which the contemporary art world functions now, eliminating the necessity for the IRL-dimensions of the process.

Discussions that pertain to the broader implications of the Internet in an industry rarely reach an objective conclusion. The art industry undoubtedly constructs a particularly challenging case due to its multilayered and convoluted business model. The argumentation may be shifted in any direction to build a persuasive case for any involved party. Artists gain significantly by creating a powerful web presence: they increase their chances of being discovered and attaining the attention of individuals who may shape their future. Additionally, a much larger audience has accessibility to viewing and becoming familiarized to the work of countless artists through a net simulacrum. Whether they simultaneously “lose” by offering their presence is ultimately subject to their ideology.

In a brusque manner, Saltz asserts that the only criterion in evaluating gallery shows are the sales they garner, or fail to garner. The critic briefly articulates–but neglects to delve into the magnitude of–how this shift relates to his identity as a critic. It would be naive to ignore how the “democratization of the critic2” affects him personally: his role becomes less important offline, as the presence of less people at galleries has an impact on the pragmatic utilization of his hard-earned credentials and expertise.

When accounting for this detail, an evident controversy in Saltz’s essay arises: initially he brings attention to the lack of a meaningful dialectic occurring in physical gallery space, while he later hesitantly adheres to the democratization of criticism by adding that “art is not inherently democratic.” What critic wants to experience others’ seeking of his expertise and input decrease? Saltz does a better job at identifying “the problem” by stating that the “the art world has become more of a virtual reality than an actual one.” Whether it ever was an actual one, or if it solely seemed so to the critic remains debatable.

“The Death of the Gallery Show” introduces a compelling argument. It is interesting to place it in the framework Thomas Frank recently utilized to investigate the authenticity of political statements of David Leonhardt on the topic of economic austerity. Frank’s methodology falls in line with the familiar traditional debate approach: “The point wasn’tfor an individual debater to believe any particular argument and win the room over with the radiance of his faith; it was for him to be able to argue anything.3”

While Saltz argues the end is near, I am not convinced he deems it possible. In a fascinating way, his performativity of argumentation is representative of the very reason galleries constitute alienating spaces for most people: much of the art presented today cannot be a catalyst for discourse. The curatorial content is no longer created for the audience, but is expected to be created by it. Certainly, this has been argued before, but the status quo of modern art has never before been as deeply interconnected with the mass entertainment industry.

The difference between Jeff Koons’ notorious sculpture of Michael Jackson with his beloved pet Bubbles and Tilda Swinton’s celebrated naps at the MoMA is a drastic paradigm of the shift that occurred within this time in the collective consciousness of reality4. Even if we are so alone in our virtual worlds that we need to be made aware of it via art, this never becomes sufficiently clear in such grotesquely self-aggrandizing projects. This intentionality in mirroring whatever the audience wants to see can be powerful, but it cannot escape being contrived. Ultimately, it appears as if the art world viewed drawing more elements from the entertainment industry as a means to attract more people and yield better sales. The performed bravado and intentional ambiguity of such contemporary art projects make people show up in gallery spaces less frequently. Why turn to culture when the culture is the entertainment?

GERMAN EXPRESSIONISM

A member of an audience that enjoys a degree of distancing from the art s/he observes would value the haunting and beautiful duality of German Expressionism 1900-1930, a recent exhibit at the Neue Gallerie. An interesting article5 connected the meaningful oeuvre of the works presented at Neue Gallerie to contemporary artwork: the grotesqueness, the intensity, the degenerate Expressionism make this a legitimate connection, from a logical standpoint. Yet for some reason the comparison feels offensive. The reason behind my revulsion towards this comparison stems from the circumstances that surrounded their creators, and what I conceive as the motivations behind their product.

While there is a tremendous amount of sociocultural commentary evident in the work of German artists who produced during that time, it is the self-imposed curatorial hegemony of Nazi ideology that carved the distinction between “what was art” and “what was degenerate.” The distinction was clarified in a public manner by two exhibits that opened at the same time in 1937, at the height of successful Nazi propaganda: Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) and Deutscher Kunst. The first attempted to frame every wrong that surfaced as the country transitioned from the Weimar Republic to the Third Reich, the second attempted to show Germans what was “ideal German:” right and normal. The construction of a shared normativity was an integral goal of the Nazi community to maintain its ideological power over the German population.

ENTARTETE KUNST (DEGENERATE ART)

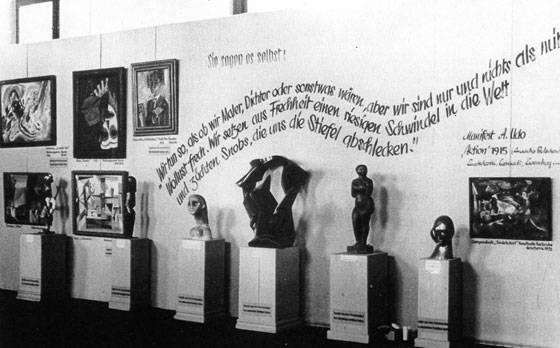

The Entartete Kunst exhibit opened in Munich on July 19th 1937, and was one of the most visited shows by German citizens. It focused on works that belonged to the Expressionist movement, being created chronologically between the end of WWI and the first years of the Weimar Republic. The populist propaganda of Adolf Hitler placed him in the position to evaluate what was meaningful and good in art: conventional realism and work resembling ancient Greek statues. Any work that did not abide to his stylistic vision–Expressionist, Cubist and Dadaist work–was labeled as unhealthy and dangerous. Entartete Kunst’s ultimate goal was to cease the production of such work: a celebratory funeral for Expressionist art.

Doomed as unrealistic and violently emotional, this artwork was publicly displayed as “the work of degenerate minds,” the exhibited work served as a sensational depiction of the sick minds of “those who could not handle reality.” The themes that functioned as excuses for the Nazis to group work as “entartet” were naturally aligned to their Race ideology: Jews, Bolsheviks, un-Christian, Socialists were all protagonists.

The curatorial organization provided ample ridicule and mocking of the artists as the commentary that accompanied their work in lieu of a regular description. To further deteriorate and diminish the significance of this art, the work was presented as a mass, piled to transcend its insignificance: it was not worth more space. The eerie and uncanny element that defines this art menaced the facade of harmonic balance the German people were accustomed to viewing as their ideal world. Any social or economic difficulties and problems the state was facing were directly linked to the aforementioned “others.” This dehumanization was a necessary part of the Nazi plan for what was to follow.

Oskar Kokoschka, George Grosz, Paul Klee, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff were some of the most heavily criticized artists. The Nazi community perceived their work as the result of a sick and distorted youth. Their staggering creative individuality was portrayed as a threat to the nation: these people were different from the Germans, thus posed a threat to the collective pursuit of a uniform Aryan identity. Most expressionists felt no inclination to belong to Hitler’s Volk, but rather felt like setting themselves apart as individual entities rather than a part of the mass.. Most of them had recently returned from the war and used art as a means to cope with their experiences, guilt and post-traumatic stress disorder. Many of these artists used drugs–particularly sleeping pills, morphine and alcohol–to self-medicate, another quality the Nazis used to otherize them as dysfunctional and code them as the source of the problem.

DEUTSCHE KUNST

Simultaneous to the persistent effort to humiliate Expressionism, Hitler and Joseph Goebbels wanted to provide an exemplary approach to art: a unifying, simple and realistic“German” art. Hitler’s artistic aspiration as well as his utter lack of a creative spine are widely known. The emphasis of the mode of art that they wanted to promote was one devoid of the complexities of human nature. Nationalist themes were prominent in this exhibit, which was naturally curated in an elegant and spacious manner; every piece given adequate space to provoke the appropriate response of respect and admiration from the audience.

Restricted to the clean replication of visual imagery, this sort of art is constrained to evoke nothing more than beautiful landscape or the beauty of Apollonian bodies reminiscent of Greek Kuri and Muses or a strongly homoerotic superhuman figure. While all of these subject areas are visually pleasing, they give no space to create work that is visceral, that is political, that instigates a strong reaction or dialectic. Even when the subjects were nude they lacked any sexual element, emanating a discomforting vibe of a pedophilic nature or an undeveloped sexual maturity. One of Hitler’s favorite artists was Adolf Ziegler, whose painting Weiblicher Akt (1942) depicts a young woman who is a clear example of this sexual nonchalance. Adolf Ziegler’s statues–largely influenced by the work of Michelangelo and Auguste Rodin–are illustrative of the superhuman figure the German man was to try to emulate: the intended aspiration, the everyday hero.

Generation Faux-Degeneration?

Bearing in mind the atrocious circumstances under which the artists of the “New Objectivity” movement created work, it seems blasphemous to compare them to the much more mysteriously self-destructive and unexplained violence. It is not that the similarities are not there thematically; they are. But it feels unfair to compromise something as painful as memories of dismembered bodies seen at war to the performed trippy violence of Bjarne Melgaard’s exhibits.

Melgaard work is surrealist too, there is no doubt. But it cannot possibly derive an equally strong emotional or intellectual response when placed next to Otto Dix or Max Ernst. For Dix and Ernst, and for most of the entartet artists art was a means to escape, for Melgaard it is a means to exist. He has clearly drawn from the Die Brücke and German expressionism, but seeing his influences and saying one is reminded of Melgaard does not seem prudent in the linearity of history. The argument is there, in Melgaard’s art too, but it cannot be as compelling as the truly “degenerate.” Gladly, in a contemporary setting these degenerates have attained the status of respectability that the deserve, one that makes the nationalist simplicity of Deutsche Kunst seem unaware at its best.

The virtual dimension of the art world exists in its 3-D gallery space. Unlike Saltz’s fear of its virtuality being a result of online simulacra, it most often is a result of the intentionally elusive artist, whose frustrating silence allows for men like Charles Krafft to become respectable figures and attain cult status6. Physical galleries will certainly continue to exist, but if there was a truth to be shared in them in the first place remains quizzical. Showrooms of the past serve as proof the “democratization” of the art can be adjusted to serve larger purposes, weighing the impact the online inclusiveness of more in an art dialectic as a positive change: a more true democratization.

1 http://www.vulture.com/2013/

2 Academic/ institutional distinction or an education are not required of a casual online entity publicly criticizing art.

3 http://harpers.org/archive/

4 Our current reality gradually morphing into a trippy hyperreality, one in which the personal is the most political due to the depth of individuals’ solipsism.

5 galleristny.com/2013/03/

6 http://www.newyorker.com/

– – –

Elias is a generalist writer and an aspiring human being based on Avenue D.

Tags: Elias Tezapsidis, Jeff Koons

a compelling analysis. Well done.

[…] (NOTE: Big Chunk of this comes from a vintage essay I plagiarized, which you can find here ) […]