Behind the Scenes

“WE DO WHAT WE WANT” – A Conversation with Spork Press

The Southeast Review will publish a review-essay I wrote looking at recent books by Carrie Lorig, Ariana Reines & Carina Finn. After I finished the review, however, I realized I was at least equally interested in the aesthetics & mechanisms of the publishers behind these books, as I was in the content. As publisher of H_NGM_N, I’m often making decisions & choices, trying to forge ahead, trying not to fall behind. And while I may know why I do what I do, it occurred to me that I know very little about why other people do what they do. So, I reached out to each of the publishers with a very targeted back-&-forth interview exchange in mind, a few quick questions to get behind the scenes a bit which I hoped would also help inform my reading of the works they produced.

In the following interview (conducted sporadically from early July through early September, 2013), I talk with the shadowy secret society known as Spork, publishers of Thursday by Ariana Reines. What started as an email exchange jumped almost immediately to a Google Doc, allowing all of the various tines of the Spork to check in, to comment, to correct, to dissemble.

Nate Pritts: Spork has been with us, in one form or another, for a long time. Other online journals & small press publishers flare up & then vanish, but you’ve worked toward a kind of durability that’s inspiring because it seems to come from innovation & improvisation & invention – not adhering to a rigid company code book, but always presenting the work in the ways you think are best at the time & for the times. Is it fair to say that this sensibility is a key to the kind of work the press is interested in? Amidst your changing web faces & prolific distribution/publishing methods, is there a core that has remained stable? How do you hold something together that iterates & iterates?

Richard Siken: Drew knew, at the very beginning, that anything run “by committee” ends up dumbed down and washed out. So we decided that if someone, anyone, said yes to something then it would happen. If you get a handful of interested, exciting people together and always say yes then something, everything, begins to resonate. I think Spork is the residue of several well lived-lives. It changes as we change. Mission drift is part of our mission. When we feel like putting out a magazine issue with several authors, then we do. When we want to have an event, then we do. Right now we’re invested in our chapbook series. The covers look the way they do because Andrew Shuta is brilliant and he gets to do whatever he wants. The stable core: we honor each other’s vision. The innovation and improvisation: we spark off of each other’s vision.

Andrew Shuta: I’d have to agree with Richard: Spork’s maxim is and always has been, WE DO WHAT WE WANT. If you don’t like that, oh well. We’re interested in producing things that we’re interested in and hope that others will find interest in our interests. (We also like repetition, as our production methods are very repetitive and turn us into human-robots that are allowed to smoke, drink, talk, and goth-out while we make stuff). Also, you’re right Nate, we are a solid core of people who are interested in the object and the content, the structure and the chaos, the perfect and the imperfect. I like that we can say, “let’s do this” and then we do it. And we often say, “let’s do this and this and that,” and sometimes we do this and that, but often not this or that. Last night, Drew Burk said he wanted to have a D&D game and turn our game and our experience of the game into an object. Will we do it? I don’t know, but we sure can if we want to. <— that’s the beauty of Spork.

Drew Burk: To be clear. I really just want to play D&D. I want to play it with these people I spend all this time with, doing this equivalently geeky thing that requires what I imagine is a similar level of geekiness and focus. And it should not be construed that my intent is to do a thing aiming to produce a clever product, but instead the intent is to explore this thing that is essentially storytelling, and to explore storytelling in an arena with stakes, with some kind of risk involved, even if the risk is only to our paper characters that we’ve rolled to create and endow.

The recording of it is a secondary proposition, occurring to me only after talking up the storytelling-with-stakes-involved aspect of it. We put all our love and sometimes our blood into these things we make of other people’s stories, of their poems… so much into these things that are final products, that are objects. And we work equally hard on our own stories, our poems, our things that we intend to eventually become someone else’s objects. I want us to create for ourselves a space where we can engage in risk-based storytelling, with no real object as a result in mind. Any recording we might do would be, like I said, secondary to it, and more of a thing for us to look back on ourselves in our special private moments.

Siken: Ask for a true story, you’ll get a lie. Ask for a tall tale and the speaker will betray herself/himself. You draw from what you know. I want to play D&D (I get to be the Dungeon Master) to hear myself lie through my sources. This is an actual desire to play D&D and also an allegory for Spork business, process, and praxis (aka Funtimes). Jake will have to Skype or FaceTime, because he lives too far down the street.

Jake Levine: Just as a sidenote, while members of Spork have in the past pretended to be Asian girls, in D&D games or not, I am actually living the Asian girl life in Asia. (Who is the most goth now?) I think it is my anti-modernist stance as a Marxist, how I regulate Spork outside the capitalist paradigm from abroad. (sorry, I’ve been reading too much Negri and Hardt and thinking about how that affects how we publish things…. which I think it does…) Compared to other presses, we have a strong anti-democratic anti-liberalist flavor. I mean nothing works in a kind of systematic, this is how we publish your shit, CLMP approved way. We just do it and it gets done and it is organic and has a kind of energy and flow that is not really logical in terms of capitalist production (which does legislate artistic production) but fucking works anyway. Some of us disappear and re-emerge and disappear again. Life works that way. So should art, if it is art. What we do is art. People expect presses to function like Wal-mart. I was telling Drew a long time ago, let’s run a contest! I did that for like two years. Drew was like ‘fuck you’ and now 3 years later and in Asia as an Asian girl, I finally understand. Thanks Drew.

By that I mean Drew is kind of the ideological godhead behind what we do. He is also the spine and heart. Richard is dungeon master. Shuta, special effects and stage production. Joel Er Smith bats cleanup. I cut my lips with the paper kiss and produce the slops.

Joel Smith: As the last to enlist in la causa, I’ll answer this first question last. I think it’s Mission Creep not Drift that Richard’s talking about in his answer up above. There’s not enough water in Tucson to drift. Creep is sinuous, ground-covering. It’s thirsty but never satisfied. You can’t stop it.

There’s no fear in anything we do at Spork, no reactionary gimmicks. That’s what drew me to it, and keeps me coming back. We do and we make. I still don’t understand it, or even enjoy it, not all the time. Does that matter? No.

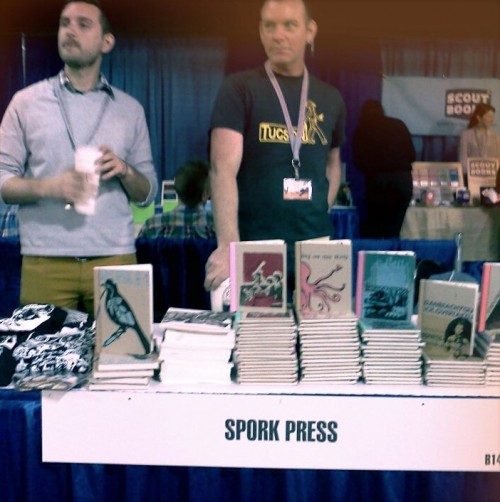

At the Pitchfork Book Fort in Chicago’s Union Park, Shuta and I were the last ones slanging books. Everyone else had packed up hours earlier. Before R. Kelly took the stage and long after he left, we held the line, selling our wares. We broke even plus enough extra to make it to the next festival. We ate refrozen cones of frozen dairy dessert out of a dumpster.

Jake’s right though, this is not some usual late capitalist enterprise. It’s late feudal, apprenticeship style. Spork is how the Dark Ages ended.

I can’t stop making the books now, or clocking in weekly with Drew, Shuta, and Richard. It’s like this magnetic, spleen-like force, a disgust with the as is and a hankering for the maybe could be. Gratitude for both inertia and hard work. Onto the next one, Dr. Pritts.

NP: This sense of adventurous risk-taking is a really obvious component of the Spork DNA. The site itself, as well as the various delivery methods we’re talking about, convey obvious enthusiasm for the work being presented, as well as for the process whereby the work is disseminated. Also, it’s clear you guys share a rare bond, you all love each other, & that the press is an extension of that – the excitement of discovery, the rush of sharing with others. I wonder, then, if you see Spork more as a kind of art project than a publishing company – though I’m deliberately setting up a binary where none needs to exist. “WE DO WHAT WE WANT” seems pretty liberating as an organizational mission statement but is there an overarching trajectory – other than continuing to exist? Put a different way, Richard says the chapbooks are the focus right now – do you know what comes next or will what comes next happen when you know what it is? Also, are you worried that the magazine will go stale while you focus on the chapbooks, or that the chapbooks will languish when you move on to what’s next? How do you maintain a level of enthusiasm for, & support of, the work you publish after you’ve moved on to the next phase?

Shuta: The chapbooks are the focus at the moment and we have a queue full of amazing books/authors that we’re going to release in the next several months and into the next year. But, chapbooks are not our only focus because, as you suggested, Spork is more of an art project rather than just a small-press. We’ve released a mixtape (you know, an actual cassette tape mix, not just a digital release like a majority of contemporary artists are releasing). I mixed music we like and listen to in the studio and we created a home for them. The tapes’ home were actually more difficult and time consuming to make than our books. We’re going to make more of them, make more of them to share our sensibilities to our people, make more of them because we like them. We like tapes and records. We’re also going to be releasing music from bands we like. We have 3 releases slated for a cassette tape release, and hopefully, if we have the money, a vinyl release too (the first release being Young Family, a collaboration between Chicago author/producer Sam Pink and Portland aritst/author/musician Kelly Schirmann).

You see, we were joking about another Spork slogan just the other night while we were sweating our asses off making books. I mean, really, Richard had just changed his shirt and his new shirt was soaked in minutes. Anyway, so we were joking about a new slogan for Spork: “Spork Press, barely breaking even since 2000.” And my point is, we have plans, lots of plans, but we have very little money and we need money for our plans. So we do what we do: we hustle and make stuff with no resources, no funding, no one looking over our shoulders.

As for the magazine, we’re certainly not interested in producing submission-driven magazines. We just are not. When there is a concept and a group of authors whose work really supports that concept, we’ll put out another issue of Spork. We’re not worried about anything going stale because we’re hungry and stale or not, we’re going to make it taste fresh and good and interesting. Especially because Drew Burk is the Gordon Ramsey of Tucson. And the chapbooks will never really be stale since we have to freedom to change up how the book looks after each production run. Each run is fresh and each book is unique.

Burk: Chapbook, the word itself, is a meaningless word now, like Hipster or Chef. So we just call everything we do a chapbook. The magazine, that’s a chapbook, as is the mixtape — as are the mixtapeS, since #2 is in the mixing phase of its tapiness — our chapbooks (them what are in the series of things that are generally the same size and shape) go from 24 to 80+ pages, and we’ve got a 200+ page novel coming out, and that’s a chapbook too.

There are enough of us that we can pursue multiple directions and ideas simultaneously; also, we learned (probably we learned, though I’m not certain that we have fully internalized the learning, but we can at least parrot the things we purport to now understand) to stop fucking around with deadlines. They don’t work. We can’t meet them. Sometimes we’re ready early, sometimes things are ready simultaneously, and sometimes people like me suddenly get jobs that require 90 hours a week for a few months, and our processes are currently too dependent upon me being the one doing a number of them, and so things crawl and/or crash to a sudden halt. And then people get upset with us, and then we make it right with patches and kisses and stickers, and then they’re not mad at us anymore, and then Drew gets things under control at the job and shows up at the studio, and then the ex-intern who loves us shows up, as does the new intern, and then it’s all hands on deck again and we make so so many books. So, right now, while the books are doing really well, it seems sometimes like that’s all we do, which translates into a yearning for something ELSE, and we keen and cry and while we fold and sew and tear and glue and press and check and fix the things we put too much glue on, we dream aloud of these other things, and then Drew or Shuta or somebody sends off a query, an email or whatever, just stepping away from the work for a second to start another process.

This past Tuesday, I stepped away to email Steve Moore, one half of ZOMBI (a regular on the Spork turntable), one half of VCO Recordings (whose releases are very familiar with the Spork tape deck, living pretty much on the device rather than ever finding their way home to their shelf or pile or drawer in the card catalog), to ask who does their duplication, and Steve wrote back and the what-about/what-if conversation went from potential to presently active. These cassette releases, like I said, they’re chapbooks.

We never stop making anything, there is never a next phase, but instead a kind of metastasis, our spreading into everything. We produce in batches, and things change batch to batch; no SOPs beyond the most basic and structurally necessary (i.e: the books must be books, each thing we make must be the thing rather than an examination of, questioning of, exploration of the possibilities inherent in, the thing(s)), and this necessarily results in each subsequent batch being a refinement of and improvement upon the last. That we are able to always employ our best and most recent practices and procedures, without it being any big deal, helps. That we actually NEED to continue to produce these objects, that helps too. That people want what we do.

The magazine: I still love almost everything we’ve published (except for the stuff I never liked in the first place). I think issue 4.1 is still one of our best ever, and it’s almost 10 years old now. I think we’re blind to au courant, trend, fashion, blind to everything but our own desires and predilections. What became stale for us was the process of it, the submission-driven journal—I couldn’t see the purpose of it. I’m happy that there are people who fully understand the purpose of it, I just don’t. People don’t know this about us, but we’re currently working on two issues of the magazine. One poetry, one fiction (specifically SCI-FI. I have always wanted to do a sci-fi issue, but some years ago everyone got all excited about sci-fi, so I — rare for me, since I tend to be so unaware of anything going on — decided to chill out and wait for everyone to not care anymore, so I could do sci-fi for love rather than fashion).

If there is some kind of organizing principle, overarching trajectory it’s—it’s what we buy when we go out shopping, you know? Spork makes the things we want to see in the world. Spork is the change we want to see in the world. If I gave a crap about shoes, probably we’d do shoes too. But when I have the moneys, I go to bookstores, I go to the record store, I search for tapes everywhere… I have always bought ink/glue/paint/thread/board/paper instead of food. So it all just makes sense to us to do what we do.

Siken: A point that could be overlooked but should be mentioned: all of us are educators as well. Cumulatively, we teach workshops and community classes as well as High School, Undergraduate, and Graduate level classes in visual art, poetry, fiction, book-binding, English, and English as a Second Language.

Burk: From the very very first, from the beginning, we have always included instructions and explanations, diagrams and charts and graphs and supplemental materials and extended invitations to anyone who wants to learn — we, or at least I, have always wanted EVERYONE to do this, to start their own journal, their own press, to put their hands to the every single everything of a book, and part of it is that I think when you put your hands on every page, when you print every cover, when you go without sleep, when you don’t pay your rent because you’ve bought supplies, when you jeopardize your own well-being so that a book might exist, it sort of changes your expectations re: level and quality of work. That’s probably why Joel reads all the fiction submissions. I get so angry at/about what people think is a publishable thing.

Levine: I don’t live in America so I haven’t held any of our physical books in awhile, but Shuta is always sending me pictures. The online is a chapbook that just keeps going. We’ve consistently put out poetry and fiction once a week for several years now. We don’t have that big of a team, so I think it is pretty remarkable. I started doing online poetry over 3 years ago, so it’s kind of crazy to think since then we’ve published over 150 poets. Shuta was recently in New York and meeting all these poets we’ve published and I thought it’s rad to make poems, but to facilitate, to house and honor the work, that, at least to me, justifies the creative act. You’ve got to make space to make love I think. Take that any way you want.

I think right now our physical chaps differ from the online in that the online gives us an opportunity to discover and expose new voices and talent. Some of the relationships we make through the online become physical projects, Feng Chen and Heather Palmer for example. None of the online relationships have become physical though, much to my own dismay.

Smith: The online component slices two ways. Like Jake said, it opens us up to new voices, new scenelets. Everybody always touts the Internet as liberator. But it also ossifies in really dangerous ways that we work hard to resist. Like, say Ms. Dvorak and Mr. Qwerty have already been published in Lit Mags X, Y, Z. Now they have an expectation that we’ll greenlight their brand-new poem / story just so they can collect the set. That’s hollow, perfunctory. There’s no aura there.

One of Spork’s only guidelines is that we want no bios, no list of pubs when submitting to us. Other places say that, but it’s disingenuous. We’re not gatekeepers or toll-takers. We’re paperboys, carnie hawkers, and that’s why we’re in the online game.

NP: Not gatekeepers but clearly some kind of gateway. Which is to say that not only the CONTENT of what you publish but also your ethos, your MEANS, seem to be giving an implicit sense of how one might comport themselves in the field of contemporary literature. Rather than one thing, several. Instead of a single voice, a multitude. I’m curious, personally, in an idea I can’t quite form — if you’re so interested in the choir, how do you pick out a soloist? I suppose this is a way to talk about what I wanted to start talking about, the new Ariana Reines collection, THURSDAY. How did you come to publish that, what was the process like in this specific instance?

Shuta: It was weird because I was with several members of the Spork crew when we first walked into this two-story blues club in downtown Chicago. We were in town for AWP. There was this blues legend (whose name I can’t remember) playing a mean blues guitar to a half-packed venue and we’re thinking that we’re at the wrong place, until we follow the stairs to the second story and end up in a sea of writers, all drunk and sweaty. So, I’m carrying an armful of Joyelle McSweeney’s Necropastoral chapbooks. And by armful I think it was 10 or 15 books, and I was basically holding onto them as if they were babies cradled in my arms. Our books are kinda heavy, and I think I had been carrying them for about an hour, so I’m pushing my way through the crowd because I see Joyelle and I want to unload these book-babies from my arms. Just as I get to the front to say hi to Joyelle, she goes to the performance area to start the reading up (I believe she was emceeing and also reading, which is amazingly apt for her). I turn around and the sea of writers has enveloped me, and I’m stuck front and center with an armful of books, every aspect of my being blocked by drunk and sweaty writers, blocked even from sitting or kneeling. And the readers are great, even though I’m cramped, sweating and about to pass out from heat exhaustion. I wasn’t just there to drop books off, I was there to see some poets I really like and one of those poets was Ariana Reines. She pulled out her Macbook and told the audience she was going to read a new poem, a long poem, a poem titled after a weekday. Even amongst the clatter of beer bottles and murmur of poets whispering secrets to each other, Ariana’s voice loomed over the clamor. When she finished, the audience roared and whooped and clapped and stomped. After the reading, writers lined up to say hi to the readers so I was stuck with my book-babies until everyone got their face time in. Fortunately, Joyelle introduced me to Ariana after the chaos died down (mostly because people needed to buy more beer) and she loved the way the Necropastorals looked and felt. I asked her if she wanted to make a chapbook with us. And she said, “Yes, how about THURSDAY?”

Burk: We went to this reading in Chicago, and it was packed packed packed. Shuta went to find Joyelle and we tried to get into the room where the reading was happening, but instead just got beers and stood near the doorway to the reading room and drank the beers and heard maybe every twenty-fifth word of the reading, washed in intermittent cascades of contextless applause and hooting, until Shuta materialized and said “We’re gonna publish Ariana Reines. She’s fucking badass.” And we said Cool.

We tried, some while ago, to decide by committee, to make our deeply-held and felt personal arguments for and against things, thinking that consensus was that path to presswide happiness and satisfaction, but that simply was not the case. If any one of us has a project we want done, we all put our hands to that project, whether or not we’re behind the thing itself. We’re behind each other, and that’s all that matters on the press level. I’m a fiction guy, and had little to no interest in poetry for a long long time, but this thing we do, where we touch every page of every book, over and over and over, we get immersed in each of our books, regardless of what we initially thought, and — I’m just gonna declare a universal here (though it doesn’t necessarily apply to Jake, since he’s crotchety and Korean) — we come around to an understanding of the merits of each book that no amount of cajoling or attempted convincing could otherwise produce. And failing that — though I think it’s rare — still the idea that we’re working for each other produces the necessary belief in each book that yields the collective drive to see these things through. And to continue to produce them, week in and out. I think it’s a good system.

Levine: I think we’ve developed some kind of rationale, some aesthetic built on commonality. The core of us have lived in this place, Tucson, where there are a shitload of people making shit but only so many people making shit happen. I’ve been collaborating with Shuta on this or that for like 7 years. We were in a poetry class and he was in a band and I used to run this thing called the Poetry Fuckfest and I asked him to read his poems and then he played with his band and in those days everyone was on drugs and eating tater tots and in a bicycle gang and the girls wore skirts with cowboy boots and played banjo. Richard once came to one of our Fuckfests and all the Tucson poetry people came and the scene kids and it was a thing for a minute several years ago. Things change. Drew is much less angry now. Richard stopped wearing skirts. Joel’s beard is larger than mine, etc… One thing that has remained constant though is that Spork has been around. If you look into the history of Father Kino who founded the mission at the foot of the Santa Cruz, you will find a keen resemblance to the Burk tribe and the way they raise chickens in their backyard. Anyway, I think despite our differences in character, there is a level of mutual respect we have for one another and our varying aesthetic preferences tend to overlap.

Tags: nate pritts, Spork Press

Jake Levine!!!

Great interview. Love your books. Young family is good.

[…] HTML Giant talked with the folks behind Spork Press. […]

Noah Cicero!!! You motherfucker. Send me a story or a poem. I’m sick of your emails.