Craft Notes

How To Be A Critic (pt. 5)

In part one of this series, I introduced a network of ideas aimed at rethinking our approach to criticism by foregrounding observation over interpretation, and participation over judgment, by asking what a text does rather than what it means.

In part two, I expanded on those ideas.

In part three, A D Jameson unwittingly offered a beautiful example of the erotics I have proposed, following the final imperative of Susan Sontag’s essay “Against Interpretation” — which, for the record is not called “Against A Certain Kind of Interpretation” but is in fact titled “Against Interpretation” — where she writes, “In place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art.” To destroy a work of art, as Jameson’s example shows and as Sean Lovelace has shown (1 & 2) and as Rauschenberg showed when he erased De Kooning, certainly counts as an erotics, which for me far surpasses the dullardry of interpretation.

In part four, A D Jameson unfortunately embarrasses himself by indulging his obvious obsession with this series. Whereas one self-appointed guest post might seem clever or even naughtily apropos, two self-appointed guest posts (in addition to all of his contributions in the comment sections) conjures the image of a petulant child acting out in hopes of garnering his father’s attention. (Daddy sees you, Adam. He’s just busy doing work right now.) Yet, despite his cringe-worthy infatuation, the example he offers is an effective one. I applaud it. (As Whitman said, “Do I contradict myself? / Very well then I contradict myself, / I am large, I contain multitudes.”)

This time, I’ll do a little recapitulation, elaboration, and I’ll introduce other lines of flight. But first, an important note about the necessity of revaluation. (Following Nietzsche’s project, of course. Itself predicated on Emersonian antifoundationalism, of course.)

To be a critic, it seems crucial that one resists commitment to the values of others.

Ask: why should arguments be coherent or consistent? Investigate those assumptions. Uncover the implicit. See those values as personal values, not universal values. Consider the history of domination linked to them. Order in the court. The Holy Order. The Platonic forms. Barf in the mouth. Stop being hysterical. Calm down. Stick to the subject. Do as you are told. Don’t ask questions. Abide our rules. See, consistency leads to conformity, as well as the mundane. And what’s more, coherency belies experience by projecting imaginary borders where boundary zones exist.

Ask: why should the critic present a tenable argument? While the orthodoxy may value tenability, no rule says a critic must value it. And besides, if there were a rule then the critic’s job would be to break it.

Ask: why should the critic be logical, i.e. make sense? While the orthodoxy may believe it signifies a measure of success, this is only one radically myopic opinion that eliminates possibilities, forecloses opportunities, and reduces the broad spectrum of experience down to a singular heuristic. Logic is one way to look at the universe, Spock. But not the only way. Poetics is another. Pathos is another. Bathos is another. Affect is another. Quantum entanglement is another. Peanut Butter is another. Also, never forget what Tristan Tzara said about logic in the Dada Manifesto of 1918:

Logic is always wrong. It draws the threads of notions, words, in their formal exterior, toward illusory ends and centers. Its chains kill, it is an enormous centipede stifling independence. Married to logic, art would live in incest, swallowing, engulfing its own tail, still part of its own body, fornicating within itself, and passion would become a nightmare tarred with protestantism, a monument, a heap of ponderous gray entrails.

Ask: why should the critic’s ideas hold up? While the orthodoxy may find such a thing significant, the critic needn’t be obliged to value arguments that hold up or make sense or remain consistent. Nonsense is a value. Provocation is a value. Surprise is a value. Play is a value. Silliness is a value. Excitement is a value. Purple is a value. Slime is a value.

Ask: what if the critic were more interested in arguments that deteriorate, are untenable, paradoxical, confounding, perplexing, confusing, lopsided, nonsensical, silly, messy, unclear, sloppy, surprising and provocative?

Remember the words of Emerson, which I alter slightly, “Whoso would be a critic must be a nonconformist.”

Recall the final line of André Breton’s Nadja, “Beauty will be convulsive or not at all.”

Now, how about some movement?

Do you recall the short-lived but awesome series called The Home Video Review of Books edited by Julia Cohen & Mathias Svalina? Like many of the examples I used in part two of this series, it approaches criticism as a performative act, an engagement, a companion, a doppelganger. Here are three examples:

Review of If Not Metamorphic by Brenda Iijima

Ahsahta Press, $17.50

Review of Notes on Conceptualisms, by Vanessa Place & Robert Fitterman

Ugly Duckling Presse, 80pp, $12

Review of Areas of Fog, by Joseph Massey

Shearsman Books, 112pp, $16

In these examples, the review acts as a companion piece to the primary text. A creative act in itself. No interpretation occurs. Instead, the critic participates.

See also: Bianca Stone’s passionate engagement with Star Trek: Voyager in her poem “You Were Lost in the Delta Quadrant” over at BOMB. (Thanks, Nick.)

See also: Jamie Gref’s review of Aase Berg’s Dark Matter (Black Ocean, 2013), which is described by Johannes Göransson (the translator of Dark Matter) as a “very intense, affected reading of the text, describing the “stuff”, the “sheerstuff”, the overjoy stuff, the poetry that affects us intensively.”

See also: Jonathan Mayhew‘s beautiful engagement with Hitchcock’s Psycho and Van Sant’s Psycho:

If we scrutinize Mayhew’s Psycho for a moment its critical angle becomes apparent, yes, but something else emerges. Hitchcock and Van Sant fade into the background as Mayhew comes to the foreground. The creative act as critical engagement becomes a way to see the critic through the artwork, more than the artwork through the critic.

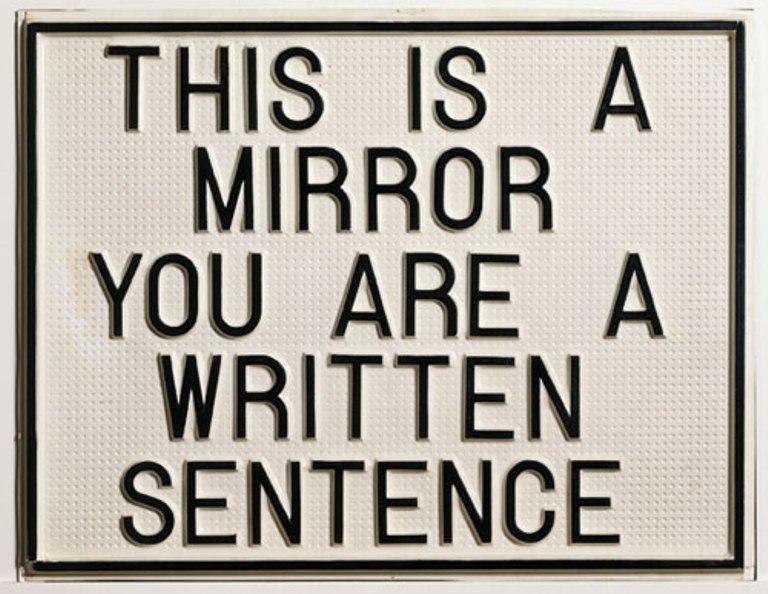

“Don’t think, but look!” as Wittgenstein said.

“People are always calling me a mirror and if a mirror looks into a mirror, what is there to see?” said Andy Warhol.

Hamlet, of course, regurgitates Aristotle when he opines about art being a mirror held up to nature. (Mimesis.)

Foucault, using Don Quixote as the pivotal artwork, suggests an alteration of our conception of mimesis from imitation of nature to representation of nature, in The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences.

While Mark Rothko said that “a painting is not a picture of an experience, it is an experience.”

Note at one point in George Landow’s experimental 16-mm short film Remedial Reading Comprehension (1970) a set of titles appear on the screen: “This is a film about you.” And then a few minutes later another set of titles slide across the screen: “Not about its maker.”

“This is a film about you / not about its maker.”

Contemporary filmmaker and poet Abigail Child borrows this phrase, tweaking it slightly, on page 85 of her 2005 book This Is Called Moving: A Critical Poetics of Film, where she writes: “This is not a text about its maker. This is a text about you.”

In both instances an interesting idea arises for the critic: when approaching the work of art, one’s observations tell more about the observer than the observed.

An unorthodox way of approaching the relationship between artwork and audience, to be sure. For one thing, it suggests that “meaning” is contained in the critic rather than in the artwork itself. Thus nothing exists in an artwork to figure out or interpret. Nothing to understand. Neither the author nor the author’s intention matters. The artwork is simply an event. An encounter. An experience. All that matters is the event and how the event shows you to yourself, or: how the event shows the critic to the critic. Yikes! Solipsism! How to handle the news that one’s response to an artwork equates to expressing one’s self and has little to do with the artwork or the artist who created the artwork? Especially given the realization that, according to Deleuze & Guattari, “The self is only a threshold, a door, a becoming between two multiplicities.”

I liked this post better when it was just the video, “Get Off My Dick” by Lil’ Booky.

served.

Who has ever suggested that traditional interpretation’s interest in “meaning” is merely an attempt to decode art, other than you? You have major issues. Also, experiencing a work of art as an event is a response to the art and a particular kind of “understanding.”

Do you enjoy arguing with yourself? It’s like you use this space to convince yourself that it’s okay to engage art. Why are you trying so hard oo convince us that it’s okay to engage art? Are you that insecure? Sounds like it.

Hi Chris,

Usually when doing scholarship, academics try to clarify what terms mean before jumping to their own conclusions. But it doesn’t surprise me that a critic committed to non-interpretation would have trouble with that.

So your argument here is that whenever a person uses a word, it means anything and everything? Well, in that case, why not just look up “interpretation” in the dictionary and see what that says? You can then write an essay that begins with the hook, “Webster’s Dictionary defines ‘interpretation’ as…” Look, I’ll even include a link to get you going.

When one actually reads Sontag’s essay, however, one sees that she is defining, and then arguing against, a very particular type of interpretation—allegorical or symbolic readings of artwork. Might be time to reread the thing (though I don’t really see why you bother ever reading anything, since you don’t care what anything means). Meanwhile I’ll write a post demonstrating how to do that, in case you run into any trouble.

Cheers,

Adam

Exactly. I’ve also read her essay, which was published in the 1960s, and Higgs completely misrepresents it. “AI” is seminal for a reason. Its central ideas are embraced by contemporary critics to the point where it’s embarrassing to see a PhD candidate pretend like the ideas therein are radical in 2013. Most contemporary critics embrace innovative and diverse methods of interpretation. For once, I’d like Higgs to tell us who he’s actually arguing against. Can you do that, Chris? Is that be too much to ask? Does anyone here oppose the methods of interpretation you advocate? Or do you mostly pretending addressing imaginary bogeymen as a way to talk to yourself?

Also, can I quote you as saying that Nazi book burnings “surpass the dullardry [sic] of interpretation”?

Thanks,

Adam

Thanks for this example of ad hominem attack. I’m actually teaching that later this week, will refer my students here.

Cheer &c.

Chris has no coherent definition of “interpretation”; that’s long been obvious. Like other terms he inveighs against (“meaning,” “realism,” “Aristotelian unity”), it means whatever he wants it to mean. Though what can you do when a person argues that a lack of coherence benefits his argument? Perhaps he’ll claim that the sky is the ground, and that my dick is made of green soap. Who knows what words will next come out of his mouth? That’s part of the excitement.

It’s doubtful, though, he’ll respond to any of these comments—daddy’s “busy,” in case you haven’t heard. Still, hope springs.

Yeah, it’s hilarious how he associates clarity of terminology with hegemonic “orthodoxy,” as if acknowledging a word’s definition means you can’t go beyond the definition.

Instead, Higgs considers it subversive to write his own dictionary. Can you imagine this fascist in a position of power, a position that would allow him to ignore the historical and social ramifications of words and essentially erase history? This is the kind of neoliberal avant garde posturing I’ve come to despise.

I’m going to be very curious to see how Chris defends his dissertation, or responds to questions during his job search, or responds to his tenure committee. I mean, look at how he slaps at me just for raising a few minor criticisms of his argument—I embarrass myself, I’m obsessed, I conjure the image of a petulant child acting out in hopes of garnering his father’s attention, and so on. I guess I’m supposed to be intimidated or something, and stop criticizing.

I wonder how Chris grades student assignments—on what basis does he evaluate student critical work? Because it seems to me that his students could respond in any way they wanted to, to any text he assigns: do a little dance in their seats, fart in his face, whatever. Hell, if Chris holds true to his convictions, he should resist assigning grades at all!

Here’s the reading list for a class he taught last fall, but it doesn’t include any information about how grades were assigned, if any. So how about it? Anyone out there a student from that class? Care to chime in?

Search Committee: “How do you assess student writing”?

Chris Higgs: “I don’t believe in assessment.”

Search Committee: “Um…okay. So, how do students respond to the texts you assign?”

Chris Higgs: “I don’t believe in ‘responding’ to texts–I only believe in experimental erotic performance. For instance, one of my better students at FSU once masturbated in front of the class during our non-discussion of Tao Lin’s experimental novel, eeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeee.”

Search Committee: “Okay. Do you have any questions for us?”

Chris Higgs: [whips out penis, masturbates, and jizzes on the face of the search committee chair.]

Do you know the Cratylus of Plato’s dialogue? –an historical figure, whom Aristotle mentions in Metaphysics 1010a as a communicator of “the most extreme opinion” by “criticizing Heraclitus [for] saying that ‘it’s not possible to step into the same river twice’, for he himself supposed [it’s] not even [possible] once.”

Cratylus’s point is that if one takes seriously the (postmodern) metaphysics of universal change, then there’s not even any ‘thing’ that changes–to say “river” is to name a consistency that, by Heraclitus’s own lights, doesn’t obtain.

(Cratylus could’ve said a similar thing about Heraclitus D6, “The sun is new every day.” If it’s new every day, the sun is new every instant–so there is no ‘sun’, because the suns one perceives–supposes one perceives–from moment to moment are actually not connected: it’s always a really new sun.)

Postmodern ontology is a problem for postmodern epistemology in a similar way when Higgs says:

If there’s nothing in an artwork to figure out, interpret, or understand, then there’s nothing in your blogicles for Higgs to figure out, interpret, or understand.

–there’s nothing to interpret at all. And to say that a piece of criticism errs by being interpretative would be an interpretation of that criticism… except that there is no interpretation–either to support or oppose or deny.

If there’s nothing to interpret–in an artwork or any ‘where’–, then saying there’s nothing to interpret is a nothing about infinite other nothings.

Rhizome! Dancing from peak to peak… on moonbeams!

Exactly. What confuses me is why he seems to take such offense.

In part one of the series, Higgs doesn’t actually “foreground[ ] observation over interpretation”, but rather, privileges description:

Think ‘description’ and ‘observation’ entail the same activity? Maybe. But here’s an interesting discussion that doesn’t scruple to distinguish between them: http://www.nieman.harvard.edu/reports/article/102825/Minimize-Description-Maximize-Observation.aspx .

I’m all for description, myself. Indeed, the criticism I do is pretty much predicated on it. But then I also call that description “interpretation,” because I’m invested in describing the artwork’s form (if it has one), and therefore defining how the artwork functions (which I think is identical to how its author intended it to function). This is formalism 101. What’s funny is that it’s also the view of art Susan Sontag takes, though she describes it in different form. It takes a bit of critical reading to unpack that reasoning in her essay, but it’s there.

I can’t describe how depressed I would be if criticism lost interpretation, and just became free response. I’m all for free response—people should react to artworks however they want to, short of destroying them, I think—but I will maintain it’s important to acknowledge that there is such a thing as interpretation, and meaning, and critical reading, and authorial intention. And to not confuse dancing in front of an artwork for interpretation.

These are of course debatable ideas and I’m happy to debate them. Much of the past 70+ years of literary criticism has been a hermeneutic debate: Do texts mean? If so, how? Who determines what a text means?

Again, I think it’s pretty clear, rereading the Sontag, that she’s arguing against a very particular kind of interpretation, namely allegorical or symbolic readings. She’s opposed to the argument that an artwork’s surface (its form) is unimportant, and that it’s the role of the critic to discover some “latent meaning” behind that surface. Say, to argue that a Mark Rothko painting is “really about depression.” And she’s quite right to argue that, I think—I agree with Sontag. What she calls “an erotics of art” is by and large what I call formalism. (That said, I think she’s totally wrong to dismiss all interpretation, and hermeneutics. Though it’s also easy to see how someone writing in the 1960s could make those mistakes—a lot of people made them, at that time.)

“Response” is interpretation, in my view. –or at least responding can’t have its interpretative aspect pared away from it.

All human praxis is a matter of “conce[ption] in the light of individual belief, judgment, or circumstance: constru[ction]” (in the words of Webster’s second definition for “interpret”).

(If something taps your knee and your foot jumps, is that ‘interpretation’? Is ‘interpretation’ that much of an Everything Word? Maybe… but that takes the discussion pretty far from what Higgs and we are talking about with, say, “criticism”; linguistic mediation is, in my view, surely a matter of conceiving in the light of individual experience — however to be qualified ‘concept’, ‘individual’, and the varieties of perspective-generating ‘experience’ are.)

To argue that ‘this Rothko painting is about depression’ is to argue that the painting represents.

Two things: a) To say that a painting, say, represents the inner state of its painter when it was painted is not not not not NOT NOT NOT NOT knot naught gnaw-t to exclude the reality that that painting is also itself. A letter on this page represents a phoneme, but it’s also a squiggle on your screen. The things that a thing ‘is’ don’t need to cancel each other; one of the least rational things about Higgs’s theorizing is the way he imposes narrow, exclusive definitions on the words and interpretations he wants to oppose.

And b) because a representational sense of, say, a painting is intuited or otherwise reasoned by a viewer doesn’t mean that that sense is necessarily wrong. One can oppose an interpretation not with a fact (‘Rothko, even in your reality, was not depressed’), but rather with another interpretation (‘I don’t see–or I don’t care about–that; I only see color, shape, brushstroke’) — that’s Nietzsche 101, and Deleuze 101, though maybe not Rhizomatic Moonbeam 799.

Hi deadgod,

I have some disagreements with this. Maybe explaining why will uncover some productive places as we continue this discussion?

Of course interpretation can be defined this way. But I think there’s value in defining interpretation more sharply: as the uncovery of intended meaning. Following from that, we can claim that there are responses to texts that are non-interpretive (for example, if a young girl dances in front of a painting).

Along those lines, if something taps your knee and your foot jumps, that is not interpretation. It is an instinctive response. There is no meaning in the knee tap. Or, the meaning in the knee tap is not necessarily related to the reaction it provokes. Here’s a way I like to think of it. If someone intentionally taps my knee to get my attention, then that is an interpretable action. But if someone merely bumps my knee accidentally with their hand, that is not an interpretable action. (If I read meaning into it, I’m mistaken.)

I’m drawing heavily here, btw, on the definition of interpretation proposed by Walter Benn Michaels and Steven Knapp in their 1982 paper “Against Theory” (PDF). See in particular their example of the “Wave Poem.”

Absolutely correct. The issue here is representation. If the painting represents something (in this case, intended meaning), then it does so in a systematic way that is part of the form of the painting and can be interpreted.

We agree here, I think, but the crucial point is the presence (or absence) of representation.

Again, I think we agree; the question is whether representation (of intended meaning) is or isn’t part of what a thing “is.”

I might phrase this differently. I don’t think Chris does enough defining of terms, or enough imposing narrow, exclusive definitions on his terms. He’s rather slipshod in that approach. I think. It’s hard to tell, though, since he’s so inconsistent, but I think that inconsistency is part of what I’m describing.

Agreement. Again, the issue is representation.

The question is whether the critical interpretation accounts for all of the elements of the form. If representation is part of the form, then interpretation must account for it. For instance, if a painting includes a traditional symbol (say, a woman being offered an apple by a snake), then any thorough interpretation is going to have to account for the presence of that symbol.

What Sontag was opposed to in Against Interpretation was the assumption that all artworks contain “latent” or symbolic meaning—and that the primary task of criticism was to uncover that meaning. Sontag called that behavior “interpretation” but I would argue (for reasons I hope are clear above) that this is not interpretation—at least, it isn’t interpretation as Knapp and Michaels have defined it.

Again, it’s not that this is the way it has to be, or that these terms should be defined this way for all time. I consider terms useful when they accomplish something. I think proceeding according to these definitions is useful and practical, for various reasons that I can try and clarify if so desired.

It’s always a pleasure discussing these matters with you,

Cheers,

Adam

Thanks.

I really stick at “intended”. The experience of any humanly made object just isn’t limited to or (completely) governed by its maker’s(s’) intentions. Meaning overflows its intentional governance.

When one looks at, say, Poussin’s mythological and Biblical representations, one’s knowledge of their direct narrative antecedents is called forward (and, at least a little, shaped by Poussin’s treatment of them). This connection of image and effectual history is surely a great part of the experience of the paintings that Poussin has ‘put into’ them–an effective intentional framework.

But consider Higgs’s earlier treatment of the Eva Hesse sculpture: when one looks at a Poussin painting, one doesn’t just see Greek/Roman gods or Biblical scenes; one sees color brushed into shapes in an array that makes pattern of itself.

And one looks at these images not as Poussin did, for Poussin never saw paintings by Velasquez, Cezanne, Rothko. One’s eye interacts with the paintings partly under the exercise of their priority, but partly too under its own experiential authority: a mix of discovery and imposition. To put it tendentiously: when you look at a Poussin painting, you see things, under the government of your eye’s experience, that Poussin didn’t ‘mean’ there to be.

And likewise with the narrative moment itself of each painting: you don’t see a Last Supper or labor of Hercules as Poussin did or painted; you see the Last Supper or Herculean labor as you already know them–however incompletely or tentatively–to be.

It’s my view that intentional considerations, however useful, are not historically or culturally dialectical enough.

I’d meant–and should just have used the word–reflexive. A reflex is, by definition, not mediated consciously; your hand jumps away from heat ‘by itself’. (I meant a doctor’s hammer-tap just below the knee.)

But if someone bumps into you, it is interpretable: as you’ve interpreted your own example, it’s an ‘accident’. Gleaning that understanding–namely, that the person hadn’t “meant” to touch you–is as much an interpretation as that the person on the other side of you ‘wants silently to get your attention’. A lack of conscious intention is the pragmatic meaning of having been touched accidentally.

Sure: unreasonable imposition on any experience is self-deceptive. To suppose one really knows Rothko’s–or, indeed, Poussin’s–inner state when they were painting, well, that’s probably a leap without definitive or conclusive evidence. –not necessarily wrong, but not of the same type–of a much weaker type–of inference as, say, that a snake offering an apple to a naked woman is a depiction of Eve being tempted in the garden of Eden.

I don’t see why intended meanings–ones that can be fished out of one’s experience–don’t have a history within which they mutate, and don’t co-exist with accidents (which are interpretable as such). Rothko’s ‘abstractions’–not the best term… ‘non-representations’?–aren’t pictures ‘of’ things they’re not, as Poussin’s ‘representations’ are, but they are records – of brush, color, density, viscosity, canvas texture, and of hand and eye–of ‘Rothko’, the whole person, which might indicate something like “depression” or “loneliness”. And likewise with Poussin’s paintings: they actually are records of Poussin, however fruitless or delusional one’s attempt to recover ‘him’ from them.

[…] Does she mean any and all interpretation, as my fellow contributor Chris Higgs recently argued? Or something else, something more […]

[…] Here’s a powerful glimpse from his latest, which seems to reverberate across a similar body of water I attempted to canoe sometime ago with my “How To Be A Critic” posts: […]