Craft Notes

Joe Wenderoth & Colin Winnette Talk WCW’s Spring And All

For this series I’m asking the writers I love to recommend a book. If I haven’t read it, I read it. Then we talk about it.

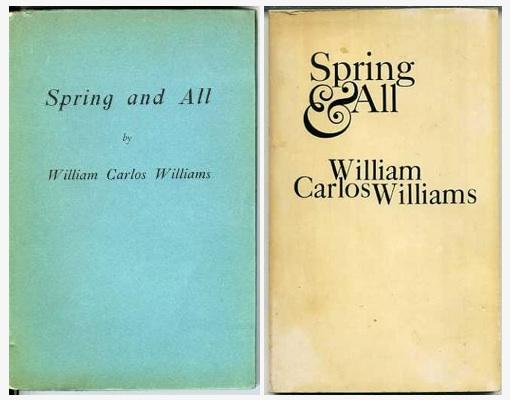

For this installment, Joe Wenderoth recommended Spring and All by William Carlos Williams.

Joe Wenderoth grew up near Baltimore. He is the author of No Real Light (Wave Books, 2007), The Holy Spirit of Life: Essays Written for John Ashcroft’s Secret Self (Verse Press, 2005) and Letters to Wendy’s (Verse Press, 2000). Wesleyan University Press published his first two books of poems: Disfortune (1995) and It Is If I Speak (2000). He is AssociateProfessor of English at the University of California, Davis.

Colin: First off, I’m interested in why we read what we read. Can you talk a little about what brought you to the book? What were the conditions that led to your picking it up for the first time, and why did you want to talk about it here with me?

Joe: I’ve been a full Professor for about 3 years now—I guess they don’t change the bio on the UCD website. why bother with correcting this? well, to become full prof you have to fill out a bunch of forms, and I would hate to think that it was all for nothing. I was doing a reading at the new school in ny and Robert Polito introduced me, saying that Letters to Wendy’s was a uniquely indescribable book, akin to Spring and All (at least in that respect). anyhow, as I had not read it, I figured I should. it took me quite a while to figure it out, but the process was always rewarding so I kept on with it and ultimately found it to be one of the best books in american english. it is a remarkably prescient book—seems like it could have been written yesterday. it seems especially remarkable in that it was written in response to “The Waste Land” (and Eliot’s much celebrated poetics), and in that its implicit criticisms of Eliot’s poetics was so far ahead of its time. it is hard for me to believe that Eliot was taken as seriously as he was. now, only undergrads are fooled, but back then, Williams was quite in the minority, and totally obscure as a poet and thinker.

Colin: Walk me through your experience of this book. It takes so many forms simultaneously: criticism, manifesto, a book of poems, a single poem, self-analysis, polemic, just to name a few. Do you have more than one approach to reading it? Do you/have you studied it in any kind of rigorous or structured way, or do you read it simply for what sticks?

Joe: I have read every word closely. I’ve taught a class on it—a class reading just this book. and I’ve taught it in other courses, too, in l briefer focus. it took me awhile to see how it all fits. I don’t see it as a single poem. I see it as a manifesto, with poems interrupting every now and then to demonstrate his thinking.

Colin: Could you bullet point a few of these “implicit criticism”s you mentioned before? Not as a defense of the statement, but rather as a potential guide/reference readers picking upSpring and All for the very first time? It’s largely an experiential text, though Williams is fairly direct when positioning himself relative to his potential critics and other approaches to poetics, but I’d love to hear your particular articulation of these criticisms, stated as simply as possible.

Joe: In a letter to James Laughlin, Williams wrote: “I’m glad you like his verse; but I’m warning you, the only reason it doesn’t smell is that it’s synthetic. Maybe I’m wrong, but I distrust that bastard more than any other writer I know in the world today. He can write, granted, but it’s like walking into a church to me.” In a letter to Pound, he referred to Eliot’s work as “vaginal stoppage” and “gleet.” In many ways, the church Williams refers to might be taken as a symbolic manifestation of the shelter of so-called Western tradition. Eliot left the church… or rather, the church fell down. And what did he find outside of its ruins? A Waste Land. A place where our alleged intelligence—especially concerning our conception of ourselves—has failed utterly. A place of cruel stupidity (which he mocks), impotence (which he grieves), and despair (which he attempts, albeit somewhat half-heartedly). Well, Eliot then went back into the church, however gloomily. Its ruins was enough, apparently.

In any case, Williams and Eliot are in agreement about the failure of the church, which is to say, the failure of our conception of ourselves. Darwin, Marx, Nietzsche, Einstein, Freud, etc…. The progress of Science, both poets agree, has obviously caused a great disruption, emptying out our previous conceptions. What they disagree about is the significance of this disruption—its impact on human consciousness. When Williams experienced the church falling down around him, he was heartened. He saw his departure from the hushed space of tradition as a great liberation, and the collapse of the church as a stroke of luck. An escape from a gloomy place. The failure of past intelligence (traditional understanding) is something he acknowledges—but it does not cause him distress… because he feels The Imagination is still in working order, and still functions—perhaps functions even more powerfully as it becomes more capable of shedding false intelligence.

Moreover, while the church has fallen, a wasteland has not resulted. Williams marveled, I think, at how Eliot could look at the most explosive blossoming of human action in all of history (all the new building and technology advancing at exponentially greater speeds) … and see nothing. “o meagre times so fat in everything imaginable…” is a sarcastic line. THERE IS MORE FOR THE IMAGINATION TO AFFIX TO NOW… THAN EVER BEFORE. For Williams, the church has been torn down IN ORDER TO CLEAR THE GROUND FOR GREATER STRUCTURES. Poem XV. speaks to this rather explicitly.

“The decay of cathedrals

is efflorescent

through the phenomenal

growth of movie houses….”

Or poem XIII. which describes New York–all the action, the vitality of it. “Waves of steel”–NYC is building skyscrapers in 1923–it is growing and becoming NEW in many ways. It is even alive–the the poet touches the living heart of it when he writes. Look at the open heart surgery (also new) at the end of the poem–the veins and arteries are the bridges and tunnels connecting the boroughs.

And when we think about church, we need to think of its function–the function of tradition. In America, tradition–supported by the churches, and following in the path of europe’schurches–functioned to maintain hierarchies. “Whites” above nonwhites, xtians above non-xtians, men above women, etc… Eliot left America (returning to the relative monoculturalism of england) because it never properly established a church (i.e. a tradition). The so-called melting pot, for Eliot, did not amount to a step forward so much as a step back–the loss of “our” culture. He was anti-semitic, racist, and more convinced by the fascists than by the democracy-pushers. We arrive at the basic disagreement, which hinges on Whitman’s assertions. Eliot disagrees with Whitman–multiculturalism is, for him, NON-culturalism–it is the loss of culture, and as such, the great threat to so-called Western civilization.

This is why I love that line from Williams’ letter where he says that Eliot’s work makes him feel like he’s walked into a fucking church. He says “church,” but I have added the“fucking” because that is the spirit of the line. That is, translated to 2013-speak, Eliot’s work made him feel like he had walked into “a fucking church.” Having grown up catholic, and having been an adult now for some time, the line resonates with me. The weirdness (and wrongness) of that church atmosphere… is hard to explain to someone who was not subjected to it.

Colin: Along those lines, there are certain books each of us likes to keep nearby at all times. I don’t look to them for instruction, but for something like encouragement or a tonal reminder of what I’m hoping to do/respond to. Or to remind myself why I’m doing what I’m doing. And while a book like Spring and All seems particularly designed to instruct, or to elucidate the possibilities of a certain approach to poetry, it also contains some of the most celebrated work by Wiliams (“So much depends…”, for example), Williams achieving exactly what he describes himself at setting out to achieve, as you said. As a teacher, is this a book you assign to young poets? And, if so, can you talk about particular experiences you’ve had doing so? What’s your hope? How have your students reacted?

Joe: yeah, for me it’s a heap of Celan books, the 1855 Leaves of Grass, Emily Dickinson (I would love to have those books with the handwritten poems, i.e. the facsimile of the writ-out poems), Spring and All, and The Dream Songs. probably none of that is all too great for young writers, but who knows. it’s great for the talented ones, that’s for sure. of all of those, Spring and All may be the most difficult. takes a lot of patience and reading aloud. and again, keeping Eliot in mind as an antithesis is quite helpful. “o meagre times so fat in everything imaginable….”

Colin: It could be argued that the success of the poems on their own is enough to position Williams appropriately, and to make his points without necessitating the accompanying prose, which telegraphs his intentions. From your position, of the work as a manifesto with poems included as demonstration, are the poems secondary, or do the two forms interact with one another in other profitable ways? Does the juxtaposition bring something to the work as a whole that wouldn’t be accomplished otherwise?

Joe: I don’t know. The way I might describe it, if forced to do so, would be to say that it is like personhood, which contains both rhetoric and poetry. What makes it tricky is that it is rhetoric ABOUT poetry. I once saw a program that had on it narcoleptic dogs. The dogs were okay–i.e. in no danger of falling asleep–until either really delicious food was introduced, or another dog was introduced. When either of these things occurred, the dog would go unconscious. He might wake up a minute later, but if he was still next to the food or the other dog, back he went to sleep. For me, spring and all talks ABOUT a phenomena, and in doing so somehow brings the author closer to causing the phenomena to actually happen. It never feels forced to me–his transitions. The other side of the coin is: the closeness to the phenomenon’s actual occurrence functions to keep the rhetoric alive with an awareness of its insufficiency. Genius.

Colin: The edition you’ve recommended is a facsimile of Williams’s original work, recently republished by New Directions. It contains typos, incomplete sentences, and other“errata,” as detailed in the back of the book. This fragmentation drastically altered my experience of the book. To me, it lended a kind of liveliness and energy, a kind of fervor to everything. I was more forgiving of tangents, potential contradictions, or self-indulgence. Some of what looks like error, seems purposeful (the orderless numbering of “chapters,” for example), and lends a palpable excitement to the text. In your opinion, what does the book gain, or lose, from these choices? Would you want to see a “corrected” version?

Joe: I think you’re right about the energy/fervor it brings, but my argument would be that it is largely for show, much the way that someone spells things however they like in an email. it is to say: I have this power—language itself cannot exist without human beings—cannot go forward. and human beings are creatures of pleasure, mischief. it is notable, I think, that most of the typos/liberty-takings are in the prose. in the prose, the poet is USING language to explain his experience of poetry. the personality experienced in the poems is different from the personality experienced in the prose. the prose is often clever, whereas the poems never are—could not be. and why? because the poems are not written by the poet. the poet has only one power in this book and that is to “allow the imagination to try to save itself.” (please look this up or have me do so—just to check the quote is exact) it is noteworthy, too, I think, that the poems are all correctly ordered (roman numerals from one to whatever, with only one error/exception). the space between the poems seems similar to the space between poems in one’s life, i.e. is the fervorous space of living and opinioning and explaining and showing personality—and this is why it need be less “clean,” to put it in williams’ terms. poems are sites of unusually deep cleanliness—i.e. the absence of self-concern and presumed agency. and no, I would not want to see the book any other way—indeed, when one does (in other published versions), one sees errors that are actually significant. I think the new directions book is beautiful, and the corrections in the back work fine. it is hard to tell if williams himself offered these corrections, but most of the time it is unimportant (or an issue of style) anyway (spelling). the last thing I will mention is that I think there is a history of writers of color abusing the english language—intentionally. william CARLOS williams used his middle name for a reason. he uses spanish style quotation marks, you might notice. this is “corrected.” my point is that the preciousness of the english language—all of its conventions—is challenged by these writers. williams is early on in this phenomenon. he manages to challenge the preciousness of the english language, yes, but his doing so never compromises the quality of the text, i.e. there are no meaningful corrections to be made.

Colin: Discussing Shakespeare, Williams says,

“There is not life in the stuff because it tries to be ‘like’ life. First must come the transposition of the faculties to the only world of reality that men know: the world of the imagination, wholly our own. From this world alone does the work gain power, its soil the only one whose chemistry is perfect to the purpose.” (61)

Talk to me about the imagination. Your relationship to it, your understanding of Williams’s relationship to it.

Joe: “….only as the work was produced, in that way alone can it be understood.” (61) “The most of all writing has not even begun in the province from which alone it can draw sustenance.” (61) what he is saying here is that most poetry is a confused and fruitless attempt to make something “like” life. the poet posits (or presumes) that there is such a thing as life, and that he stands somehow apart from it, such that he can describe what it’s “like.” he is offering shakespeare as the opposite of this mistake—shakespeare’s works (and all works“of value”) are not “like life,” they are themselves life. they are not a description of life—they are themselves life. he is saying that the kind of writing that produces works of value refrains from creating a space between “life” and the poet. to create such a space is to falsify one’s situation considerably, and to turn one’s work into “art.” as with celan, “art” is a disparaging term for williams—it implies a falsification of the poet, a removing of the poet from “the province from which alone it can draw sustenance.” shakespeare’s works are so great—so alive—because they were written from the province they speak to. now, to bring williams’ use of the term, “the imagination,” into it. the simplest way to understand his use of the term, I think, is to think of it as grammar in the brain, i.e. grammar as the seeing tool it actually is. as such, “the imagination” is possessed by no one. the imagination can be engaged (and is engaged continuously, for the most part), but most of the time we are not aware of it. most of the time, that is, the imagination is mistaken for one’s self, or at any rate one’s self’s power. in this state of affairs, the working of the imagination is concealed, such that the self can mistake its work for “reality.” in our everyday state, we conflate the imagination and reality, as though the imagination is seeing what is actually there. williams—1923— knows enough to understand that “reality” is not something that could ever be contained by the imagination. williams calls reality “black wind,” which is to say, calls it a vague force (poem V.). he also calls it “impossible,” and “impossible/ to say.” the imagination cannot register the identity of reality… because reality is obviously changing—always changing. reality is movement, not identity. poem VIII. is instructive on these points.

VIII.

The sunlight in a

yellow plaque upon the

varnished floor

is full of a song

inflated to

fifty pounds pressure

at the faucet of

June that rings

the triangle of the air

pulling at the

anemonies in

Persephone’s cow pasture —

When from among

the steel rocks leaps

J. P. M.

who enjoyed

extraordinary privileges

among virginity

to solve the core

of whirling flywheels

by cutting

the Gordian knot

with a Veronese or

perhaps a Rubens —

whose cars are about

the finest on

the market today —

And so it comes

to motor cars —

which is the son

leaving off the g

of sunlight and grass —

Impossible

to say, impossible

to underestimate —

wind, earthquakes in

Manchuria, a

partridge

from dry leaves

he begins the poem with acknowledgment of reality’s presence, i.e. sunlight on a floor. of course this is also the presence of an onlooker, who has a certain Experience of that reality. poetry only becomes possible when the onlooker is able to cut the Gordian knot implicit in “ordinary experience.” In ordinary experience, reality and the imaginary representation of reality have become indistinguishable. The poem, for Williams, is the act of cutting these two things apart.

For eliot, the imagination has been crippled. for Williams, “The Imagination” has not been crippled so much as it has simply been developed, or enabled… by changes in what we know and how we live. Williams clamored for Newness just as much—or more—than Pound, but his conception of Newness was quite different. For Pound, newness was in history, and through history’s terms. It meant a furthering of the story (the tradition) of the Western world, even if this furthering was, as it was in Eliot’s case, an alleged apocalypse. For Williams, newness was a more radical thing. Newness, for him, did not exist primarily in history, on the level of specific consequent situations—no, for him, newness was primarily the newness of “all.” In Williams’ poetics, that is, human identity (individual and cultural) is not furthered by poetry—it is resurrected, whole, from nothingness. On this point, again, he follows Whitman:

“…. Past and present and future are not disjoined but joined. The greatest poet forms the consistence of what is to be from what has been and is. He drags the dead out of their coffins and stands them again on their feet … he says to the past, Rise and walk before me that I may realize you. He learns the lesson … he places himself where the future becomes present. The greatest poet does not only dazzle his rays over character and scenes and passions … he finally ascends and finishes all … he exhibits the pinnacles that no man can tell what they are for or what is beyond … he glows a moment on the extremest verge.”

And Whitman again, from the climactic lines of the first poem in the 1855 leaves of grass (untitled, but later called Song Of Myself) :

Somehow I have been stunned. Stand back!

Give me a little time beyond my cuffed head and slumbers and dreams and gaping,

I discover myself on a verge of the usual mistake.

That I could forget the mockers and insults!

That I could forget the trickling tears and the blows of the bludgeons and hammers!

That I could look with a separate look on my own crucifixion and bloody crowning!

I remember . . . . I resume the overstaid fraction,

The grave of rock multiplies what has been confided to it . . . . or to any graves,

The corpses rise . . . . the gashes heal . . . . the fastenings roll away.

I troop forth replenished with supreme power, one of an average unending procession….

First, consider “he finally ascends and finishes all.” All. An important word for Williams. Spring… and all. Williams says: “the inevitable flux of the seeing eye toward measuring itself by the world it inhabits can only result in himself crushing humiliation unless the individual raise to some approximate co-extension with the universe. This is possible by aid of“The Imagination.” Raising to some approximate co-extension with the universe means… conceiving of ALL. Something of which one is but a part.

As God comes a loving bedfellow and sleeps at my side all night and close on the peep

of the day,

And leaves for me baskets covered with white towels bulging the house with their plenty,

Shall I postpone my acceptation and realization and scream at my eyes,

That they turn from gazing after and down the road,

And forthwith cipher and show me to a cent,

Exactly the contents of one, and exactly the contents of two, and which is ahead?

What God is for Whitman, The Imagination is for Williams. What “myself” is for Whitman, “No one” is for Williams. In these lines of Whitman’s, he is on the verge of becoming a corpse—mere material, mere contents. He may stave this possibility off only by following God with his eyes. Following God where? Who knows? In any case, to follow God in this way is to leave home, to abandon the furthering of the past—and to abandon the idea that one should be occupied with trying to stay, and to fix one’s identity. Time moves, and a consciousness always has to decide whether he will allow himself to be carried by it… or whether he will resist, and try to stay home (try to shape and safeguard one’s own autonomy/personal identity).

Williams: “I let The Imagination have its own way to see if it could save itself. Something very definite came of it. I found myself alleviated but most important I began there and then to revalue experience, to understand what I was at —” Williams’ use of the word “at” here is telling. We can take him to say that he began to understand an idea—his idea—but with Williams, there are no ideas but in things. Thus, we can take it literally and conceive of him as a spectator “at” a show. What is the show? The show is experience, i.e. the present. To be at the present is to pay attention to it—to not sink away from it. How does one stay at the present? The Imagination.

“The Imagination, freed from the handcuffs of “art,” takes the lead! Her feet are bare and not too delicate. In fact those who come behind her have much to think of. Hm. Let it pass.” The Imagination is muse-like in this passage—and always female throughout the book. Persephone, of course, is the other female figure he uses to figure The Imagination. she is a dark figure, not just because she lives most of the year in hades, married to death. she is also dark in that she does not serve (white) power. look at the end of the book:

Arab

Indian

dark woman.

Arab—historical foe to the xtian. Indian—indigenous ghettoized people of america (crowds are white). dark woman—lowest possible position in the society, in terms of power. and yet—this is The Imagination he speaks of—his version of “God.”

The Imagination, like God, is the force that has opened up where we are. We live, in ordinary experience, in the space The Imagination has produced, the space of memory, but The Imagination itself (its living self, its action) is always ahead. We follow behind it—we let it take the lead—when we want to understand what we are “at.”

Colin: It seems like you’re describing a lifelong project, a state of being, rather than just a momentary goal / a means of producing art. Do you view these modes as separate, or is the project that of their ultimately being one and the same?

Joe: Yeah, for Williams, it was definitely “a practice.” Your readers should mos def go to youtube and search “william carlos williams voices and visions.” You’ll find a documentary about his work–surprisingly good. And part of it is a visit to Williams’ actual doctor’s office. Williams was a baby doctor, and did much of his work in the homes of the people living in his city–door to door, delivering babies. (Eliot was an office clerk of some sort–banker? what was it?) Life and death. Anyway, this doc takes us to his office, which is still in use…by WCW’s son, who looks alot like his dad. So one feels as if one is looking at Williams himself–as if one could somehow be in the presence of Williams alive. I guess I thought of this because of the word “practice.” The film is really about that word, and how that word fit the way Williams lived. Poetry for Williams was a practice, and at the same time an escape from his practice. I think of poetry this way myself. There is the practice of self, and there is the escape from this practice. The escaping, if it goes on long enough, can become a practice itself. The practice of escaping the practice. Person become poet. Poet alleged to be person.

Williams points out also the impossibility of the core. That’s where the poet is–at the core. Everything else–everything around the core–is movement, action. The practice of self is perpetual movement, an indefinite towards, in the realm of actions. The practice of escaping the practice of self, i.e. becoming No One, i.e. letting the Imagination try to save itself, depends upon stillness. Only stillness (no-self) allows for a living sense of the myriad movements of and in the all (of which he is but another moving part).

I would like to go up to people and say, “you don’t know where you’re going.” It is an alarming proposition, but an obviously true one. It is the proposition Williams makes. Each poem, in its own way, says: you don’t know where you’re going. In so saying, its intention is not to help you or to prompt you to learn where you’re going. Rather, it is to challenge you– it is to challenge your presumptions with regard to orientation. It is to show you that you know less than you thought you did about the future–it is to show you that you don’t know the future at all, and thus, do not know where you’re going. Robbed of your presumed future, you are freed to be “at” where you are–you are free to be in the present. Relieved of your own movements (and their always forward looking perspective) you are free (enabled) to take in the movements around you. There is the poem about the gypsy in heaven. (I don’t have the book handy–it’s later on, I think, in the book) The poem in essence says that a gypsy is laying beneath a tree, looking up into its leaves, which are “so many,” and “so lascivious and still.” The all (the tree, here) is made up of parts, leaves. This poem is about the stillness of the parts. This stillness of the parts is always an illusion, or even a delusion. At the slightest wind, these leaves will erupt into chaos, the tree a whole other entity. The lasciviousness of the leaves–of every part of the whole–is their desire for movement, contact, change, merge. The gypsy “smiles” at this momentary illusion of an unchanging whole.

It’s not about the movements of the person so much as it is about the movements of the universe. Williams is simply marvelling–I think people today always want to ascribe some socio-political intention (or concern, even) to poems (and thus, “poets”). I think Williams would say that poems are only ever falsified by such intentions, because they imply (and require) a sense of the future that is precisely what poems mean to destroy. Poems, in his view, may have a powerful impact upon a socio-political sphere… but they cannot haveintended to do so. Put another way: the power of the poem is the power of witness. If one is impacted by a poem on the level of the socio-political, it is not an impact stemming from the author–no, it is stemming from witnessed conditions, i.e. actuality.

I was asked to think of Williams in relation to migration. At first, I thought, yes, obviously, there is the gypsy figure in the book. Williams himself stayed in one place. New Jersey. He went around in circles in that place–that was the place wherein he moved. So he, the person, did not migrate. Did he, the poet, migrate? I don’t think so–I think migration sort of implies an intended destination, and Williams the poet had no interest in “getting anywhere” as he was “there” already. So a gypsy is someone who moves around all the time, but without any real intended destination. The gypsy laying beneath the tree (at the core) (Kore). The all is the tree, the many leaves in one place, one identity. The all changes from moment to moment. The all is illusory, and the foundation of the self. This is what pleases the gypsy. The lasciviousness of the leaves (of grass). The unseen but deeply felt desire to merge with the other–to fuck, to die. The gypsy “smiled.”

Another good metaphor for this is in the cathedral-gives-way-to-movie-

But scism which seems

adamant is diverted

from the perpendicular

by simply rotating the object

cleaving away the root of

disaster which it

seemed to foster. Thus

the movies are a moral force

We’re at the movies. “The decay of cathedrals” has allowed for the growth of the movie house. Here, at the movie house, we watch a movie. In the movie, “scism,” which is to say, a tearing apart, “seems adamant.” Seems. Only seems. And that is the key–the tearing apart can be “diverted/ from the perpendicular….” Perpendicular to the moviegoer is the screen. The tearing apart is threatening to occur there, in that screen, i.e. in the perpendicular world that that screen produces and develops. Thus, it is rather simply diverted. The root of disaster, because it exists in a pretend world, is simply cleaved away. How? “by simply rotating the object..” I read this several ways. First, the movie projector, which creates the perpendicular world by rotating reels of film, divided into “still” frames. Just keep on cranking that baby and the movie will end–presto, disaster resolved. By rotating the reel of film, every troublesome frame is rendered impotent.

Another way to take“the object” is as a human head. Turn your head away when scism seems adamant. Simply rotate your frickin head. You have (and feel) the power to look away. The most decisive turning of our heads is when we turn around and exit the theater at the end of the movie. We turn away from an artificial all and are faced with a their own real all again. “Thus/ the movies are a moral force.” They teach us to be aware of our power to look away (from them), and to look instead at where we are. They allow us to see the difference. They differ, in this respect, from religion, which was always trying to teach us that they are the same, i.e. that the imagined world IS the real world. Those days are gone.

– – –

Colin Winnette is the author of three books: Revelation (Mutable Sound), Animal Collection (Spork), andFondly (forthcoming from Atticus Books, August 2013). He lives in San Francisco.

Others in this series:

Tags: Colin Winnette, Joe Wenderoth, spring and all, william carlos williams

The 100th commenter can have the copy of this book Joe Wenderoth and I used for this interview.

vary nice

i’m actually in the middle of letters to wendy’s. i read it on the train to work every morning and i feel like it permanently does something to my workday. spring and all has been on my reading list for too long. thanks for this interview, really wonderful.

This is the 100th comment.

It might very well could be…

[…] Joe Wenderoth & Colin Winnette Talk WCW’s Spring And All | HTMLGIANT […]

First, thanks for the post, best I’ve read here in quite a while

but one has to be suspicious of his fashionable taste for Williams & Pount over Eliot–not merely because Pound was a fascist (actually broadcast for Mussolini &c.) and Eliot wasn’t, that is. Or the troubling Williams issue of gender. The verse of the effeminate Eliot is a “vaginal stoppage”–no one sees any problem here? And of course the line of misogyny runs through Williams in various ways, some of them less troublesome than others. (seriously, tho, the way he fetishizes the “dark woman,” we’re gonna let that slide?)

Painting Eliot as simply missing the point of affluent modern society is to misread his work entirely. Eliot is a *modernist*, his early verse very explicitly draws on the French moderns, and his problem with modernity is not simply with “multiculturalism” but with a generalized dehumanization (keeping in mind his position relative to the brutal two world wars) and bureaucratization. Eliot’s got affinities with Giacometti, with Bacon, as much as he (and many of his followers) would disavow them.

(The really interesting movement, I’d argue, would be an attempt not to criticize Eliot but to excavate a more interesting Eliot. One might start with the early verse, with the essays before they solidified into New Critical dogma, with The Family Reunion, say; a marginal Eliot, one whose acceptance and success in a sense destroyed him just as it might have destroyed Kafka to be put in the limelight.)

(Or, hell, to find a postmodern Eliot–a writer whose reflexive pastiche is the obvious opposite to Ulysses in that it betrays a *distrust* of metanarratives (in Lyotard’s terms), a writer whose view of the importance of tradition is not a stultifying obeisance to the past but rather a prophecy of intertextuality. This is all there for those who look.)

Er. *this fashionable taste. Not meant as some sort of personal attack.

tinyurl.com/l3cselt

[…] or even Latin I would do so. But I cannot” (5). Joe Wenderoth also argues this in an online interview, and claims that Williams’ “O meager times so fat in everything imaginable” is an ironization […]