THE ACT OF MEMORY, “LAST YEAR AT MARIENBAD” & THE THING OF INTENTION

SUBJECTIVITY OF MEMORY

Suzanne Corkin’s book Permanent Present Tense: The Man with No Memory, and What He Taught the World chronicles the fascinating case of Henry Molaison. Upon receiving a catastrophic lobotomy at the age of 27, Molaison continued his life as an individual incapable of forming new memories. For the remaining 55 years of his life, Molaison was closely studied by Corkin: his unique tragic circumstances constituted him as a one of a kind empirical specimen of anterograde amnesia, the medical term for his inability of forming new memories. Corkin found in him the ideal means to gain a deeper scientific understanding in the field of neuroscience[1].

Unlike the Drew Barrymore character in 50 First Dates, Molaison spent his amnesic reality in the company of a meticulous observer and not the romantic goofiness of Adam Sandler. The focus of Corkin’s book is the scientific exploration of how new memories are cerebrally processed. Corkin observed the short-span consciousness of Molaison’s new memories along with the variation of the feelings and thoughts he exhibited, as everyday provided a new opportunity to reassess her specimen all over, evaluate and reevaluate the pertinent data. Despite the repetitive occurrence of the same questions within his short-span of memory, Molaison’s responses were sometimes indicative of the formation of new memories. This analysis served as a catalyst for a new neuroscientific theory: contrary to previous popular belief that memories “were indelible snapshots of sense experience, stored in chronological sequence like the frames of a celluloid film,” memories are actually located in more than one location in our brains.

Mike Jay’s exceptional review of Corkin’s book[2], aptly entitled “Argument with Myself,” starts with a powerful definition of memory. Jay concedes that memory shapes one’s identity, but he argues that in addition it simultaneously functions as the (mis)apprehension of a well-founded, whole self: “memory is not a thing but an act that alters and rearranges even as it retrieves.” In this framework, it is evident that the way we conceive our individual realities, as they are constructed by all the memories we hold, are suspect. The manner in which all of us accentuate the details of what happens, both to us and in the world surrounding us is marked by subjectivity. While the degrees of each person’s paranoia and tendency for narrative exaggeration vary, there is no doubt that in most “realities” much is not real.

In an endeavor to make her students grasp this very fact, Mary Karr once began teaching a creative writing course by performing getting in a huge spat with the educational institution’s program director[3]. Once the program director exited, Karr revealed to her students the argument they had witnessed was a simulation. She then asked them to write down their observations and perception of the incident. The students had an arduous time reaching consensus on a collectively agreed objective account of what had just happened in their classroom. This exercise swiftly presents the validity of the very ambivalent nature of objective memories.

LAST YEAR AT MARIENBAD (1961) : THE BEAUTY OF CONFUSION

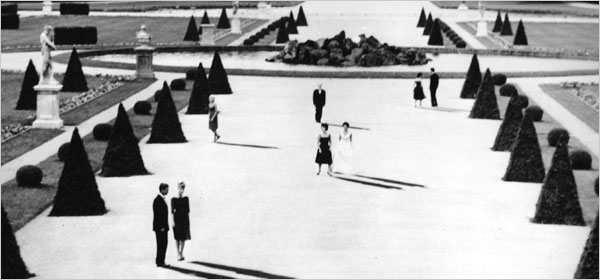

Last Year at Marienbad is a highly acclaimed and often polemically debated French film directed by Alain Resnais and written by Alain Robbe-Grillet. Much of the controversy surrounding it is linked to its foremost oneiric quality. The viewer is never fully certain of an absolute truth in regards to what version of the same scene presented on repeat but in entirely different milieus is real. The solely three developed characters remain anonymous through the entirety of the film, though the themes of romantic trauma and memory arise remain prominent throughout.

The film features an edifice of magnetic architectural beauty, with baroque decorative details that resemble the Versailles in their grandiosity and pompous–yet still dignified–extravagance[4]. The hypnotic voice of a narrator describing the ambiance eventually concludes to a scene where a man addresses a woman. He passionately asserts that they had met the previous year in Marienbad (a spa) and he is certain that the woman is there for him, in anticipation of their scheduled reunion. However, the woman contradicts his belief by stating that she has never met him, coldly dismissing him. The ominous presence of a second man, who acts possessively in a way that implies his romantic tie to the woman, recurs as the force that disables the woman to give in to the first man. Numerous scenes are inserted in what appears to be a chronologically haphazard manner, and the repetition of puzzling dialogues make it clear that the audience is not watching one story, but many different ones, or even segments of many different stories.

The anti-climactic narrative mechanism the film employs defies chronological linearity and actively introduces the audience to the blurry dimensions of memory. The cinematic saga also verifies Jay’s definition of memory as not a thing, but an act, both literally and figuratively. The way in which the man’s memory of the meeting emerges throughout the film in varied forms informs us that there is no one objective plot to grasp. Rather, the film successfully evokes powerful emotional empathy from the audience by showing us how one reality that appears as a foremost objective truth to one individual (the first man) may be repressed, suppressed or truly subjective to another one (the woman). The numerous layers of gray are further multiplied by the (re)actions of the second man, as he potentially responds to his partner’s infidelity, encompassing the threat of losing her and vengeance.

Marienbad validates the definition of memory as an act: the characters display selective patterns in how they form their “objective” realities. Memory can only be subjective for the characters of the film, because their “objective” realities are based on the premise of individual memories, memories that are formulated by what each individual assumes to be an objective reality, always suspect. The elusiveness of an objective reality explicates the viability of the first man and the woman remembering things in a radically different manner, without necessarily leading to either of them being erroneous.

The masterful creators of the film–writer Robbe-Grillet and director Resnais–certainly emphasized the beauty of confusion and seeked yielding the freedom of the interpretation of what is occurring in the film to the audience. This is what divides the reception the film receives: many viewers fail to comprehend that memory extends beyond a thing to an act. The viewers who grasp thatMarienbad does not try to one-up them intellectually by saying nothing fall under its cinematic spell. Instead of giving momma-birding them something trite, the writer and director generously give the optimal amount of space to maximize their emotional response by projecting what they decide to fill in the plot’s blanks. The film mirrors the viewers’ ability to resign their need of constructing an objective reality; informed confusion signifies a much more meaningful rapport. If the viewer wants to see nothing, that too will be there. In the end, the first man and the woman exit the hotel together, but they do not appear filled with sentiments of jocund romance. They seem like spirits that will return to the hotel to continue attempting the identification of a mutually shared objective reality.

INTENTIONS: MEMOIR AND REALITY TELEVISION

The reason the films’ creators ought to be applauded for Marienbad, is their impressive awareness in triggering both a warm and visceral response from the audience sans cheapening the experience. Rather than presenting one picture, they presented countless: they welcomed the confusion of the viewers. While the incentives and motivations of the characters–along with their names and identities– remain quizzically mysterious, they also always appear “possible.” The viewers can fill in the gaps and following the route the main premise of the film directs them to: create their “objective” realities.

Mary Karr is an established authority on the subject of literary memoir. The genre is probably the closest form of creating an artful product that primarily is of a truthful nature, with “too subjective” exceptions being highly-criticized for being disingenuous, whether selected as Oprah books or not. While Karr aptly personifies an individual who appears to be candid, she does not deny that she keeps herself safe by shielding whatever foremost private facts she denies sharing. “Everything I wanted people to know I’ve already presented,” she stated in a recent interview[5]. Karr’s awareness in regards to her alcoholism allowed her to conceive that it was routed in her evasion of her true feelings. Ultimately, this created a vicious cycle, in which Karr–being unaware of true self herself–did not believe others when they were affectionate towards her: others could not know her individual objective reality, because she did not know it either.

Karr proceeded by criticizing visual media for its superficiality and its sloppy representation of the human psychology. The apotheosis of this superficiality, Dr. Drew is someone Karr thinks should be shot for the exploitative nature of his shows: his insincerity offends Karr. To an informed media consumer, Karr’s accusations ring valid. To an excessively overinformed media consumer who welcomes trash too, it brings to mind Alexis Neiers.

Neiers–whose existence if you are not aware of please try to keep it so before you become fascinated by the absurdity of her fame, brand, career and identity–serves as evidence of the power the vulgarity the oversimplification of human psychology. Neiers openly discusses her heavy drug use during Pretty Wild, but her lack of seriousness in regards to how she understands her current sobriety and broadly how she perceived her reality is severely subjective, if not myopically delusional. “I believe that, in some weird way, this whole thing with the Bling Ring, this whole reality show, is going to give me an opportunity to help people,[6]” declares the young mother before identifying Dr. Drew as a career paradigm and praising his benevolent nature.

THE PURSUIT OF (A) TRUTH

A sweet confusion is the most honest gift we can give to someone we immensely care about, it is the greatest gift of complete intimacy. To challenge them to think outside of their usual patterns, to make them see that much beauty lies in liminality and transition. If not necessarily beauty–because many people would prefer an absolute truth or a sense of closure over uncertainty and a transitional status–at least, meaningfulness.

– – –

[4] In Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece The Shining (1980), he successfully imitates the alienating beauty ofMarienbad, ultimately constructing a character out of an edifice with the haunting Overlook Hotel.

[6] http://www.vice.com/read/alexis-neierss-pretty-wild-road-to-recovery

– – –

Elias is a generalist writer and an aspiring human being based on Avenue D. @etezapsidis

Tags: Bling Ring, Elias Tezapsidis, last year at marienbad, MARY KARR

Tell me more about Mary Karr. Sounds like you studied with her? Did you witness this false fight? What was your impression at the time? I think I would have enjoyed being manipulated in such an entertaining way. Just like art!

I met someone who had studied with Mary Gaitskill and apparently she always plays Two Truths and a Lie (where each person reveals three things about themselves, two true and one a lie, and then the audience can ask as many yes or no questions as they like until the vote, after which the lie is revealed by the liar). I love this game, and always use it in my own classes. And fun at parties too. But apparently Mary Gaitskill could never be fooled. She’s so good at making fiction feel real that she can spot the details in a story that make it feel false. I really like thinking about that, even though I’m not particularly great at the game myself.

Verismilitud is bizarre. But in my opinion an unreliable narrator is the best and only kind.

i would like to tell you more, but the only class i took w/ her was on the fix. it is pretty good, you should read: http://www.thefix.com/content/mary-karr-liars-sober91684

[…] at Marienbad was shot from a script written Alain Robbe-Grillet, a master of the nouveau roman, and memory, one of the major themes of both Marienbad and Night and Fog, his classic documentary about Nazi […]

[…] at Marienbad was shot from a script written Alain Robbe-Grillet, a master of the nouveau roman, and memory, one of the major themes of both Marienbad and Night and Fog, his classic documentary about Nazi […]

[…] at Marienbad was shot from a script written Alain Robbe-Grillet, a master of the nouveau roman, and memory, one of the major themes of both Marienbad and Night and Fog, his classic documentary about Nazi […]

[…] at Marienbad was shot from a script written Alain Robbe-Grillet, a master of the nouveau roman, and memory, one of the major themes of both Marienbad and Night and Fog, his classic documentary about Nazi […]