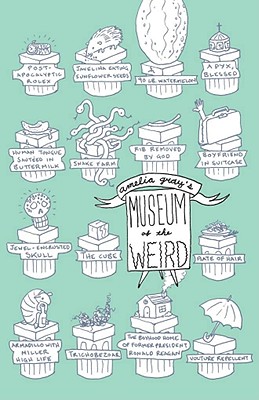

This year saw the release of Amelia Gray’s second book, a collection of texts from FC2 called Museum of the Weird. More than a simple consolidation of stories into a single body, or even a creation of texts within the confines of one body and a strong mind, Museum of the Weird seems an object bent out of the mysterious and new, taking foreign objects, mysterious relations, freak peoples, and bringing them together in a wilding chorus of the strange and, holy shit, the entertaining, addictive. Last month I traded a bunch of emails with Amelia re: the new book, how she works, the function of belief, fate, trying, and just what the hell is with all the eating of the hair that shows up all throughout her writing.

* * *

B: Amelia, your prose has an interesting quality of being at once familiar and intuitive, while also at a seeming kind of remove: beyond just using objects and animals as active elements, there is at all times a feeling that you are way back in there somewhere, narrating your way your way rationally out of these intensely messed up, or as you say “weird,” prompts. Do you think your writing is a kind of emotional propaganda? Is all writing emotional propaganda?

A: The phrase “emotional propaganda” strikes me as redundant because any effective piece of rhetoric contains some emotional element. In propaganda and in writing there is an actor with an intent and an audience, a communicating element and a receiving element. Effective propaganda sets up a world in which only one outcome is possible in the same way that a great tragic story drives its characters towards an inescapable fate. So sure, in the way each genre stands as a completed product, writing is a kind of message propaganda that ultimately stands to aid or question a cause/idea/person. Fiction tends to attack or support ideas like love or trust or babies via scenes and characters, while war propaganda, for example–thinking of WWII posters here–attacks or supports a country or cause using ideas like love or trust or babies. There’s an emotional appeal in each, driven towards a point or points.

The biggest difference is that war propaganda or motivational speeches tend to get created with a message in mind beforehand, while fiction doesn’t have to be created in the same way (though it can be). When I write, I tend to start with a very basic idea or image (all these could be described as prompts, sure) and write my way out of it. Someone creating a political image might do the opposite–begin with a larger point and work to seek out its supporting evidence–but we end up in roughly the same place.

“Propaganda” doesn’t insinuate emptiness, nor does it have to suggest a singular message, nor does it have to be negative, but it does suggest that there’s ultimately a point to every message. Same with fiction or poetry or advertising or journalism: if a string of letters doesn’t make any words, the point might be that there’s no point, or there might be a different point, point is there’s a point.

B: Once you have your idea, say, babies, how do you go about “writing your way out of it”? How do you know when you are “out”?

A: In the story I wrote about babies called “Babies,” I started with an ordinary fear of accidental pregnancy and unwilling parents and put it into the context of an irrational fear, where the baby is immediately there and there’s no time to have serious conversations or hold a baby shower or make a doctor’s appointment. The ordinary fear combines with the irrational fear and sets off a rational string of events. Obviously the woman is going to want to clean everything up. The baby is hungry, there’s no food in the house. That’s a more comic story, things are lightly touched. I could have made it more about umbilical cord infections or traumatic blood loss or flesh ripping or whatever, but I wanted to keep the real bumping up against the unreal, babies floating inside balloons. At the end I felt the impulse to make it a happy story, where the relationship is saved and the individuals are improved, and then I felt the impulse to crush that impulse in as few words as possible, and then I felt I was out. I had the plot of that story down fast, so I remember the impulses shifting. That’s not how it always goes but it’s how it went then.

B: Does this fangling with the real and unreal affect your real life? Do you find the unreal waking up because you will invoke it? Or maybe I’m asking: where are you most days when you make.

A: I have some unreal convictions and compulsions that stem from the real. People who have irrational fears still fear in rationally specific ways, in that way invoking the unreal or the unlikely, bringing it in with the real, compounding it. I don’t always write starting from fear but I think that’s where the unreal sinks the heaviest into my life.

When I was younger I’d tape secret notes to the undersides of seats on the city bus. Most days I’m sitting in a chair, but the bus is how making feels when it’s good–the feeling of stepping off the bus.

B: Do you believe in fate? Do characters in stories have fates?

A: Characters in stories have fates because there is someone directly involved in their creation and movement. In terms of real people, I believe in a pretty basic fate, not much beyond the fact that we’re all going to die. It seems unlikely that any powers beyond stick to easily sketched-out rules of kindness or evil. That said, I do worry that I’m going to get killed by a Jeep or by the owner of a Jeep.

B: Randomness. Random tragic death. There is certainly a random of the element of latent and looming fear in your stories, some of which then manifest themselves upon the elements there as if at random, or asserting themselves on what has come before it in this kind of deus ex machina way, but of a way not godlike really, but like something weird that happens to you waiting in line at McDonald’s. Are these curves yours? Are they transplants, or exhibits? What is randomness? How much of writing requires faith?

A: There’s terror in random; with little recognizable fate, it’s all deus ex mcflurry. “What will happen?” is a question answered best with a stiff kick. The impulse of writing requires a faith and a faith requires a gut. Faith doesn’t imply religion. I mean, BYOG. I’ve used some form of the word “gut” at least once in every book I’ve written.

B: You claim to hate the internet. But I see the range of odd facts appear in your writing, little manifestations of things you picked up that influences those turns of terror. How are you influenced by all this information? How did you learn to write?

A: I have never claimed to hate the internet. I think that the danger of the internet to writers is its instant gratification, the ability to look up exactly what you want to know, that leaves little room for the imagination. It’s information pornography. Beyond that, there’s the gratification of being able to blog or tweet or email every smallest kernel of a thought which otherwise might marinate into something larger on its own, without that instant aspect of publication. Twitter is snot thrown on a wall. You seem to claim that every experience you can have on the internet is a good one, which seems equally as wrong as hating it all. I learned to write from taking in information, but there’s an oversaturation point to information where it becomes a stack dump of regurgitated text.

B: Really though, what brought you to start writing fiction?

A: I started writing fiction around the time I started trying to understand things. I wrote a story because my friend kissed a boy I liked at a party and I couldn’t figure out why that had happened. I wrote another story in a philosophy class because I didn’t get the concept. The story was about fate and there was a fish in it. I hadn’t done the reading for the day.

B: Has writing helped you figure anything out?

A: It has helped me develop and attempt to support some theories. I have some theories.

B: What about sense. In “There Will Be Sense,” Arnold, the narrator with the artificial heart says, “I want to get so close to God that God has to file a restraining order.” Then he is fed a series of dinners by Jeannie, which are a measure of their days. This suggests to me a hidden order that is revealed to the one who would look. If I may quote the quote you have up on your Facebook profile (I knew you secretly loved the internet): “God will not have his work made manifest by cowards.” In fact, god is all over this book in ways. Capital G god. Were you raised religious? Do you believe in the hand of god?

B: What about sense. In “There Will Be Sense,” Arnold, the narrator with the artificial heart says, “I want to get so close to God that God has to file a restraining order.” Then he is fed a series of dinners by Jeannie, which are a measure of their days. This suggests to me a hidden order that is revealed to the one who would look. If I may quote the quote you have up on your Facebook profile (I knew you secretly loved the internet): “God will not have his work made manifest by cowards.” In fact, god is all over this book in ways. Capital G god. Were you raised religious? Do you believe in the hand of god?

A: I was raised Presbyterian and went to church almost every Sunday for 18 years. That tends to set some patterns of thought and speech, even if one is always looking for distractions while it’s happening. Organized religion was always too weirdly open for me, for what seemed like it should be such a personal interaction. I couldn’t stand watching people be affected. I started operating the sound console and reading books during sermon. This poor old usher had to come up the stairs with the communion wine. Once, I reached to take it and the plastic cup was wedged in too tight and shattered between my fingers. I remember how the usher looked at me. I think there are many fine reasons for organized faith but it also might be part of why I have trouble with eye contact.

“There Will Be Sense” is a God story about a man made out of science. There’s an order but not in the way he thinks there is. I believe in a god that started things and stepped back. I don’t believe this god has hands. I think it’s arrogant to pretend we understand the concept of a god, though arrogance isn’t all that bad. I think those ideas come through in parts of that story.

B: What was it you were reading those days during the sermons? Do you have idols (literary or otherwise)?

A: A mix of stuff I found from home and found at the church library: 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Encyclopedia Brown, the Bible, The Babysitter’s Club, Huckleberry Finn, Animal Farm, Little House on the Prairie. Once I got my hands on a brown paper bag full of mystery novels. This is over the course of some time.

Alton Brown on writing: “Seriously. I’m not very bright, and it takes a lot for me to get a concept – to really get a concept. To get it enough that it becomes part of me. But when it happens I get real excited about it.” “I can’t talk about anything or write about anything if I don’t understand it. So a lot of the stuff that I go through and a lot of the time that I spend is understanding.”

B: Where does a sentence come from? What do you most often eat for breakfast?

A: When a subject and an object verb each other very much. A sentence comes from a thought and a good one is usually reorganized.

I have breakfast trends that change weekly. The constant is milk first thing, coffee later.

B: Museum of the Weird is different from AM/PM in that it continually shifts form and voices, unlike AM/PM‘s singular expression and working within constraint. There are several sections in the new book where you use stage direction and screenplay dialogue. I was wondering if you had written in that form before, and if film or theater was at all at influence.

A: I’ve been writing in those different forms for a while. I wrote a TV spec and a feature-length screenplay around the same time I was writing AM/PM but never had much fun editing either so they stalled and sank, which is fine. Writing in those different forms is some fun. I like reading scripts, but I don’t have much of a mind for realistic staging. I wrote a short play that would require a woman to be handcuffed to a car. Another short one featured an agoraphobic, and most of it happened in this city bus fantasy she had developed over the course of a minute and a half. We staged that one for a competition and I went out back and held the wall so I wouldn’t barf.

A: I’ve been writing in those different forms for a while. I wrote a TV spec and a feature-length screenplay around the same time I was writing AM/PM but never had much fun editing either so they stalled and sank, which is fine. Writing in those different forms is some fun. I like reading scripts, but I don’t have much of a mind for realistic staging. I wrote a short play that would require a woman to be handcuffed to a car. Another short one featured an agoraphobic, and most of it happened in this city bus fantasy she had developed over the course of a minute and a half. We staged that one for a competition and I went out back and held the wall so I wouldn’t barf.

B: I think I saw you said somewhere that “Thoughts While Strolling” was one of the last pieces you wrote in the book. It also follows an unusual form, kind of like call and response. How did this one come about? Did you know you had written the last piece of the book when you were done? How much do you revise?

A: I found Harry Austin Clapp’s entry on RootsWeb. Clapp was known for beign Collegeport’s most enthusiastic booster and also known for his love of noodles. Collegeport is a tiny unincorporated community, a ferry trip and a few hours north of Port Aransas. I found he had a column from the The Daily Tribune (now The Bay City Tribune) in Matagorda County and I started reading those. He said “When I die drape my head stone with noodles and carve on the stone, ‘He Loved Noodles.'” I think he’s great. I wanted to write a response to him and the column he did, where he walked around and remarked on ordinary things and made jokes.

I didn’t know if it would go in the book or not when I wrote it or if it would even end up being a complete story. I revised that one a lot, cut big pieces and switched chunks of it around. It’s nice to write chunks that can be switched, to have each chunk have its own small arc and then piece all of the chunks into a larger arc. The last story in the book required similar edits.

B: Over what period were these stories written? How did you realize you had a collection that fit together? How did you go about shaping the collection? Were any story collections in particular that you used as a mirror or a model, in discovering that shape?

A: The oldest story was 5 years old when the collection was finished. I was returning to the same themes without thinking about returning. I’d show someone a story and they’d say Another hair story? and I would say, Really?

One thing that maybe doesn’t come across sometimes when talking about a completed collection is how little you see while you’re inside it. It’s hard for me to think in terms of overarching themes and ideas and forms in the middle of writing five years of stories, but now that it’s done, I can look back and pick things in and out easier. When I think of collections that are very complete and strong I think of Honored Guest by Joy Williams and The Night in Question by Tobias Wolff and Magic for Beginners by Kelly Link. They are good models.

B: Yeah what is it with the hair anyway?

A: Man I don’t know.

B: I think that I just realized that where there is a lot of hair in your writing, there seems almost no family. The relationships in the book are almost entirely of an intimate or inanimate nature: the characters have little history beyond what they do or are or say. Was this an active element of your composition? What are your parents like?

A: Keeping out some histories wasn’t an active choice in writing these stories, but when a story is shorter, that does seem to be the first to go. I like to think of individuals as shaped by a past that’s too complicated for succinct fiction. I don’t like it when a story presents an element of a character as easily drawn from their childhood, and I don’t like when people do that to themselves or other people, either. I’ll write red herrings before I suggest that a kid tortures an animal because of his relationship with his brother. I’ll write the kid examining a bag of peanuts for eight pages, as explanation. There’s a million reasons why a kid tortures an animal. There’s a family in this thing I’m working on now.

My parents are good people. They live in Tucson with a dog and a cat. My sister makes sushi in Portland.

B: What is this thing you are working on now?

A: I’m working on a novel. The protagonist is a bag of peanuts and the victim is your childhood dog. It is a murder mystery.

B: Do you use fiction as a way to take out anger on things you can’t control in life? Is writing an outlet? Why are you writing? Who are you writing to?

A: Writing is the emotion outlet, sure. It’s the hole for extremes. My parents had to take my door off its hinges for weeks at a time because I was slamming it so often. I started hiding pages of writing behind the posters on my wall. Writing’s still the best way I’ve found to keep from tripping into the sense-void emotion world. I wouldn’t say I take out anger or jealousy or joy as much as I try to feed and nurse and train it. Writing is an outlet, but it’s not an outlet of escape. People keep a journal when they want to escape. I write to rub my face in it.

B: Run us through a day. A day where you feel you are there, in there, rubbing your face.

A: A good face-rubbing isn’t a whole day. It tends to start when I experience something that puts a singular emotion in me. I was reading Voices From Chernobyl a few months ago and it put me in such a sick, agitated way that I was clenched up in my bed, chewing on my knuckle. I was thinking about the mothers and fathers and babies and then I lost my sense. Not for a long time, not more than half an hour. So then I was there for a little while, thinking about it, gnawing, and I wrote in my notebook next to my bed, and then I got up and warmed up some soup and then typed on the computer. The face-rubbing portion of the process is the fastest part. It can take more time to make soup.

B: I know you have night terrors. Do those get in your words? Does sleep get in your words? How much do you write by hand?

A: I think the night terrors are starting to get better than they were but it’s possible I’m just not remembering them. These days I’ll be driving somewhere and remember I had one the night before. I tried writing about them a few months ago but it didn’t work. I thought it would be easier because it’s so similar in the moment to that overwhelming senseless feeling, but it’s maybe only that way when contrasted with the rest of the room or the morning after.

Sleep gets in, though. I like to generate when I’m in a morning fog. I don’t usually write by hand if I can get to my computer. The notebook beside the bed is mostly boring stuff and the odd face-rub. I’ll start essays by hand usually too, not sure why, I don’t write a lot of them.

B: Do you ever write drunk?

A: Writing drunk is generally a waste of a drunk.

B: How has writing a novel felt different or not different from writing stories? Is there a different thing you focus on, a variance of approach?

A: I can keep the threads of a short story entirely straight in my mind while I’m working on it, but the detail involved in a novel, even at the character inventory kind of level, has been new. Short stories are all veils in comparison. My office is full of scraps and post-it notes with reminders to myself about a piece of metal that gets mentioned or that there’s a rip in the wallpaper in the upstairs bedroom. It’s fun, crazy-making. I wish Vèra Nabokov would come help me with notecards.

B: Have you found that writing a novel is more about discovery than stories? Or less, or equal to? Any novels that have helped you understand the form of the novel in your own way, besides the actual act of writing?

A: More discovery than story, I like that. There’s less control in writing a novel. My impulse is still to pare down rather than overindulge an explanation. There are a parts of novels that have helped me want to be brave in my own way. I’m thinking about the first half of Lolita, the first 100 pages of Underworld, sections of La Medusa, the pacing in No Country for Old Men, any given section of Infinite Jest. Maybe writing’s the most cowardly way to be brave.

Interviews, man. I feel like I’ll look back at this in thirty years and maybe I’ll have written a bunch of novels and maybe I’ll never write another novel but either way I’m going to be like, look at this idiot.

B: Do you see yourself doing this for the rest of your life?

A: I figure the goal is to spend as much of my life living in a way that makes me feel like I feel right now, finishing cold coffee after a morning spent writing a story. If writing makes me feel like this for the rest of my life, I’ll do it for the rest of my life, yes, of course. But maybe writing won’t always make me feel like this and something else will replace it, and then I’ll end up spending the rest of my life making candy or burning down churches.

* * *

Amelia Gray’s Museum of the Weird is available now via FC2 and elsewhere.

Tags: am/pm, amelia gray, museum of the weird

Nice.

i feel like i just watched a really good episode of american gladiators

Your comment is illogical. There are no bad episodes of AG.

“Maybe what’s redundant about the phrase is not so much that all rhetoric is emotive, but rather that all emotion is rhetorical, affected – regardless of how firmly uncalculated its expression seems. Emotion is always attended, anyway, as intention, persuasion.”

I don’t get this deadgod. I guess if you’re going with emotion as a simple internal echo, regulated to the self. What do you mean when you say emotion is always attended as intention persuasion? Maybe emotion is inherently manipulative? I guess like asking a “rhetorical question” — what was the point of asking such a question aloud if it was rhetorical, right? So you’re saying we have emotions, but the fact we show our emotions is a manipulative act?

I dunno. You’re confusing me. Please clear this up.

We love you, Amelia.

interesting read

This is so, so many delectable quotables like —

“Fiction tends to attack or support ideas like love or trust or babies via scenes and characters, while war propaganda, for example–thinking of WWII posters here–attacks or supports a country or cause using ideas like love or trust or babies. There’s an emotional appeal in each, driven towards a point or points.”

Blake and Amelia – such a wonderful discussion. I laughed out loud several times. Thanks for all you both do, this was not only enlightening, but humble as well, and always entertaining. Very cool.

“emotional propaganda”

Maybe what’s redundant about the phrase is not so much that all rhetoric is emotive, but rather that all emotion is rhetorical, affected – regardless of how firmly uncalculated its expression seems. Emotion is always attended, anyway, as intention, persuasion.

Random tragic death.

If it’s random, it’s probably not “tragic”.

The impulse of writing requires faith[.]

“Faith” means a lot of things, eh? ‘Expectation of something remote but predictable and verifiable’ – like, say, that a reader is collaboratively susceptible to effect – sounds like something every writer indeed indulges in. But ‘belief in something definitively evasive of definition, unverifiable, answering to no method of inquiry’ – ?? I don’t think writers need to be spiritually “faithful” in order to attend the sacred, or, indeed, the inexplicable.

a god that started things and stepped back

Deus absconditus, like that of Pascal or wise-ass Joyce, or the silent god who Bergman’s characters feel ignored by.

More discovery than story.

When do they not imply each other?

I always wondered how come in text interviews the interviewer’s questions are always in bold, when really it should be the interviewee’s responses bolded.

I think there’s this convention because the questions are supposed to be shorter than their answers. If they are, highlighting them in this way lets the responses between them ‘rise’. (If they’re not, it’s not really much of an “interview”, whatever it looks like, eh?)

“Maybe what’s redundant about the phrase is not so much that all rhetoric is emotive, but rather that all emotion is rhetorical, affected – regardless of how firmly uncalculated its expression seems. Emotion is always attended, anyway, as intention, persuasion.”

I don’t get this deadgod. I guess if you’re going with emotion as a simple internal echo, regulated to the self. What do you mean when you say emotion is always attended as intention persuasion? Maybe emotion is inherently manipulative? I guess like asking a “rhetorical question” — what was the point of asking such a question aloud if it was rhetorical, right? So you’re saying we have emotions, but the fact we show our emotions is a manipulative act?

I dunno. You’re confusing me. Please clear this up.

man

what the hell

i’d like to sucker punch whoever gave deadgod the dictionary and the two button mouse.

“AHEM, [deadgod] has no physical dictionary, thus can not be given it, i [deadgod] use dictionary.com; my mouse is single buttoned, bitch; ever heard of the command key?!”

stop overestimating concision.

propaganda doesn’t exist.

technically, bolding (or highlighting) either the questions or the answers will allow whatever is not bolded (or highlighted) to rise. This is the a(e)ffect of antithetical visuals. Just seems like some ego thing leftover from interviewer-school or something.

? [1]

I guess that’s about as concise as it gets.

[1] I have two dead-tree dictionaries – I’ve not seen anything on the internet to match either the OED or Webster’s New Collegiate. If I blockquote a definition, it’s directly quoted, as with “scorch”. If I just put a comma and single quotes around the definition, like: ,’x‘ , then the definition is mine, made up ad hoc, as with the two for “faith” (above).

Both dictionaries were presents from my mom, back when gifts were exchanged between us, and it would be a “sucker punch”, because she will slap you ’til your ancestors lose their teeth.

The computer is a laptop with that clumsy touch-pad. I’m pretty compuilliterate and don’t know much about that right-side clicker that mouses have and don’t have a key on my machine that says ‘Command’ (?).

I think Ockham’s Razor entails its own anti-razors; rather than worry about concision qua brevity qua succinctness qua terseness qua pith qua laconicity qua compendiosity qua misunderverbosity, I recommend attending the unity of literary cause and readerly effect. The Goldilocks Interrogative: how much is just right for what?

Further question for Amelia: How does a writer whose primary form has been these very short stories and story-like things turn the corner to write a novel, as (I think) you’re doing? What kinds of changes in habits of writing/thinking/mind/structuring/etc. is the novel requiring of you?

ha ha

spoke

too

soon

I always boldface my questions to make sure the first question stands out from the introduction to the interview.

Assuming that it has to do with ego seems really cynical. But maybe that’s just my bruised—and enormous—interviewer ego talking.

I think the questions are in bold because if the answers were then the reader would be drawn to read the answer before the question.

With that said, I think most interviewers are highly egotistical. Interviews read like a passive-aggressive competition between the artist and their inquisitor.

The above doesn’t apply to this particular interview. I liked this interview.

Yes – that’s the point, eh?: using the typeface to let the answers of an interview stand out. If the questions are much shorter than the answers – say, one interrogative sentence : one paragraph in response – , then the ‘bold’ness of the questions isn’t really the interviewer’s ego talking, but rather, her or his voice ushering the celeb upstage. Consider the alternative: an interrogative sentence in ordinary font, and a block of two or three paragraphs typed like this. That’d be an eyesore – and a quick Scroll Right Past – right?

I’m with Matthew on this: I don’t think emboldening the questions in an interview is an ego-inflating convention so much as a practicality oriented towards easy-on-the-eyeballs.

I wish it was raining because I hate every beautiful day.

Wish the poster had taken a minute to italicize the titles of things. There was one typo, as well, “beign” where she meant “being.”

True, though, that these things don’t stick out to most readers. Just those with an editorial stick up their anus. Like me.

I found Amelia’s comments about the internet to be illuminating and profound.

Hope everyone’s doing well.

And don’t forget: http://litareview.com/cgi-bin/load.cgi?0910/dl/dispatch2009-8.pdf

(I think she said that one or two of these stories appeared in Museum; I actually haven’t got hold of a copy of the book yet, but I’m pretty sure “The Darkness” appears for sure. Definitely one of my favorite things I’ve ever had the honor of publishing. I might add that it is the most popular thing dispatch has ever published, with something like 2400+ downloads since August 2009.)

Do you have a job?

You know, besides keeping all the threads straight and forcing myself to stay with characters longer, I’m actually finding more similarities than differences in terms of the day-to-day work. There’s the same feeling of sitting down to an empty page, and it doesn’t matter as much as I thought it would that there are fifty pages of writing on either side of that empty page. The page is just as empty as it is when I’m starting a short story. (Surely I’m just fooling myself. A friend of mine is up to 170 pages of what she’s still calling a short story. We have ways to trick ourselves against The Fear. But that’s how it feels right now.)

Hi everybody, thanks for reading.

Thanks, Blake, for the good questions

a fantastic and fun resource: http://www.onelook.com/reverse-dictionary.shtml

This was the perfect complement to the morning coffee. Maybe I overdid the coffee. I kinda splattered Amelia’s words all over Twitter. “Snot on a wall.” Oh well.

[…] was interviewed by Tobias Carroll for YETI 10 and by Blake Butler for HTMLGIANT, talking about books, fate, routines, America, etc. Thanks to both for the good […]

[…] 15 Dec “I think that the danger of the internet to writers is its instant gratification, the ability to look up exactly what you want to know, that leaves little room for the imagination. It’s information pornography. Beyond that, there’s the gratification of being able to blog or tweet or email every smallest kernel of a thought which otherwise might marinate into something larger on its own, without that instant aspect of publication. Twitter is snot thrown on a wall. You seem to claim that every experience you can have on the internet is a good one, which seems equally as wrong as hating it all. I learned to write from taking in information, but there’s an oversaturation point to information where it becomes a stack dump of regurgitated text.” — Amelia Gray at HTML Giant […]

[…] When I was younger I’d tape secret notes to the undersides of seats on the city bus. Most days I’m sitting in a chair, but the bus is how making feels when it’s good–the feeling of stepping off the bus. […]