Film

Painkiller post

When a man with a torn spleen and two broken ribs takes three days off from work, Netflix instant, Oxycodone, and his ability to shit again quickly turns into the center of his universe. When he is reduced by lack of selection to watching a romantic comedy whose target audience are creative menopausal upper-middle class spinsters, you know a blog post is brewing. Something’s Gotta Give (2003) is about Erica Barry (Diane Keaton), a successful playwright who, in the afterglow of coitus with Harry Sanborn (Jack Nicholson), tearfully says she had considered her body “closed for business,” a sentiment even this 36-year-old male can relate to. Oxycodone softens the edges around this world, the frayed bones directed at my lungs, the hazy glow of a movie I have no business watching, on my couch, grimacing in pain with every biochemically induced, or at least mediated, laugh. I may be high. It’s probably the drug, but slowly along the way the movie started to scare me. Perhaps it was the Kubrickian camera slowly going over each square inch of their Hampton summer house — the long contemplative and eery takes which seemed to impart meaning simply by existing in real time with the matter it was recording, as if our director Nancy Myers had just enough faith that this world was innately fucked up enough to scare the living shit (figuratively; your contributor is constipated) out of someone. Much has been written about the symbolism and space of The Shining (1980), whose quotidian grotesqueness is almost invisible, thus horrifying. To finally look yourself honestly in a mirror is to see murder.

“I’m walking down the hall,” Harry will tease Erica, having accidentally seen her in the full nude the prior evening. The endless trope of romantic comedies is the accidental titty shot, a solemn nod to our clipped desire to nurse forever. I recall sucking on someone’s breasts with infantile exuberance once, and the grossed out look on her face already planning to not return my calls. The romantic comedy counter-intuitively attempts to mitigate our adult fears by inciting our childhood ones. And the only thing worse than the male gaze is the female one, of shame; Myers sadly apologizes for Keaton’s full frontal by having Jack cower with repugnance. Nicholson seems to have turned into Burton’s 1989 Joker, sans the makeup. As for Jack Torrance’s domestic abuse-y entry into the bathroom in which bug-eyed Wendy could only scream, I worry about the partners of the many men who had the famous film still tattooed on their arms. It’s one of Kubrick’s more literal, and less interesting shots. As a healthy narcissist and loyal autobiographer, I must say that I was Danny there, my cold bum rolling down the snow, newly birthed from the crack of a bathroom window. My father once attacked my mom with a knife, she protected by a bathroom door, its weak bolt the strongest thing in her bones that night. I remembering running along the Toronto suburban sidewalk, barefoot on snow, with her, and staying at a neighbor’s house for safety. I should have tried speaking to my finger. The Shining may even be seen as feminist, with our lanky heroine prevailing at the end; or not, just a tale of oedipal patricide. One thing’s for sure. Dads are annoying.

All work and no play makes jack a dull boy, a 17th century Welsh proverb, also makes an appearance in James Joyce’s “Araby,” about a boy who tediously plans and worries about going to a market to buy a gift for a girl, only — delayed by a verbose uncle, one imagines endless em dashes of deviation — to find the market just closed and nowhere near his vision of what our young lad thought she deserved. Such dissonance of aesthetic vision and rhetorical reality is a large theme in Dubliners; I say “rhetorical reality” because, in a sense, the poetic grimness of Joyce’s Dublin is, on a literary level at least, an essentially romantic thing by which the greater Joycian vision of pathetic’s profundity is measured.

Partway into Something’s Gotta Give, Erica begins incorporating her charming upbeat dialogue with Harry into a script which would become “A Woman To Love,” something Harry called her once; events in the film’s first half become fictionalized into a stage play, and the audience is granted that meta-entry into a play that comes from the “real life” of a broader ongoing fiction — perhaps most heavy-handedly done in Synecdoche, New York (2008). Sorry if we’re getting lost in all these films, which is what Netflix instant has done to us. It seems that instant is the new God, not to be confused with the one-shot instance of our lives. The nurse told me I would feel the morphine instantly through my IV, and soon levitated I was. My bike got caught in a train track at full speed. One flew over my bike as one’s own pedestrian angel. It’s an odd moment when you can see your face without a mirror. I looked down and saw my left cheek growing out of its face. “You need to see somebody,” a nice lady said. Dating sucks, I thought. She drove me to the ER, in whose waiting room I shook her hand until forever and said thank you.

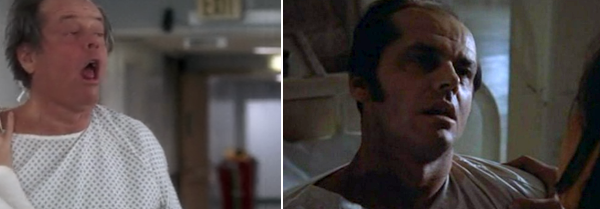

So Harry has a heart attack during foreplay with Erica’s daughter (“it’s complicated,” which would be the name of another likewise Myers film) and, high on painkillers, comes into the waiting room for a hospital gown ass shot I’d rather forget. At one point, he collapses into Keaton’s shoulder with similar post-lobotomy limpness as he did on Chief Bromden’s in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), a film my high school drama teacher had us watch, which sort of changed me forever. A visit to the psych ward will teach you that its inhabitants believe everything is just fine. If despair is the dissonance between the mind and world, insanity is when you stop noticing. Both The Shining and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest are ostensibly sympathetic to the Native-American cause; in the latter, Bromden’s obsequious deception of being a deaf mute may implicate the stunted sensory capacity of manifest destiny. Ken Kesey’s 1962 novel is written from Chief Bromden’s POV, with long drug-induced and/or -evocative passages in Faulknerian italics, as if each hallucinating letter had trouble balancing. Kesey worked the graveyard shift at a mental health facility in Menlo Park CA which participated in MK-Ultra, a covert operation run by the CIA engaged in “behavioral modification” i.e. electroshock therapy, LSD, and sensory deprivation. Oxycodone is a derived from the opium plant, from which morphine, codeine, and heroin are also made. At 5 mgs every 4 hrs, this post is possible. Every breath is a midget inside me having his way with a crowbar. Blogging ain’t dead, it just hurts.

Mr. Wills was one of those guys who might have fried his brain a little too much in the ’60s. He recited Edgar Allen Poe in Birkenstocks, screaming. I remember a story — a character study, I believe he called it — I wrote whose protagonist dies in a convenience store robbery. He didn’t save anybody. He was buying Ritz crackers. It’s a cheesy line, but I ended the story with “his blood shown as the black night,” focusing on the pool it made on the speckled linoleum, which garnered a hand drawn star and some cred. I may have been in a hurry, but for some reason I thought “shown” was the past tense of shine, thus used it erroneously; it seemed that Mr. Willis gave me too much credit, figuring that I rhetorically used the word as the past participle of show, imbuing it with sentience where there was none. I felt like a fraud, smiling whenever he did at me, like we had some literary secret. The only literary secret I’ve learned over the years is that acceptances don’t require a S.A.S.E.

Something’s Gotta Give ends in Paris. Harry — “six months later,” fully bearded, then cleanly shaved — finally tells Erica that he loves her. The word love must fit tightly around a woman’s heart like cardiac fellatio. They’re on a bridge over the Seine, the blurry lights of the Eiffel tower in the background, snowflakes meandering as flycicles before they land and melt. I imagine Nancy Myers braced similarly in front of her Macbook like her invention Erica, her meta-tastic moves (earlier, this prophetic Parisian scene was set on stage, shot at the same angle) under-appreciated by those who just wanted a good laugh. We may take Kaufman or Kubrick more seriously, and laugh at these middle-aged romantic comedies, the great actors of yesterday still churning away for the royalties. I am saddened by romantic scenes on a beach, always shot at dusk, because I can feel the cold sticky salted wind on the actors’ faces. To pretend that one is in love; to host alien-like feelings inside yourself on behalf of some greater narrative, somebody else’s; to be tired and cold.

Accidents are great attitude adjusters. Suddenly, my small life seems faintly sweeter: the pink flattened turkey breast in my fridge; still-folded Hugo Boss shirt waiting for a date; an internet I nurse every night, pumping nonsense into this mutual mess. A cloud of diarrhea in a swimming pool is a lovely thing, a cauliflower-shaped puff as a personal Hiroshima. I don’t know how long I’ll be constipated, but I realized it’s a metaphor for isolation. To be so full of yourself you include it in a film review. D.F. Wallace’s The Ennet House Drug and Alcohol Recovery House (redundancy sic) may be the most gloriously written, and the wet t-shirts of Girl, Interrupted most bulbous and mammalian, but it was in the Oregon State Hospital — where Cuckoo’s Nest was filmed — where I first found/lost myself, sitting there in class utterly shocked at what I’d just witnessed. Billy Bibbit’s suicide had nothing do to with depression or psychosis. It was guilt. He couldn’t bare his mother knowing he had found love. (Of matricide, her mattress seems like a good place.) Randle McMurphy’s state ordained lobotomy may actually be a reprieve, if we see consciousness as ontological agony, though Bromden kills him with a pillow anyways. Perhaps a certain kind of peace is undignified, that of ignorance. The uncertainty of living is quickly reduced to the certainty of death, though in the meantime we are given small things to worry about. Bromdem breaks a gated window he always could have, leaving behind Nicholson’s warm corpse already awaiting an Oscar, and heads toward the jagged black outline of the western cascades in the distance. If literature’s job is to warn us what history finally teaches us, I think I’ll wait. Mr. Wills, that devastated hippie-poet succumbed to teaching high school English and Drama, turns off the VHS, on the classroom lights, and looks right at me. He’s practically crying, and I nod.

Another great post, Jimmy. I love your work.

This is excellent. One of my facebook friend’s linked this and I trust his taste so I gave it a read. Do you write anywhere else?

you’re 36??

“The only literary secret I’ve learned over the years is that acceptances don’t require a S.A.S.E.”

So good. This is one of your best. Hope it doesn’t get missed because it was posted on the weekend.

jesus.

this is way too lucid jimmy, you should ask the doctor for stronger meds

btw that redrum line slays

http://youtu.be/8jhbQX_HSLs

Sorry to hear about your accident Jimmy. Glad you’re OK, and that broken bones don’t keep you from writing. Feel better man.