I Like __ A Lot

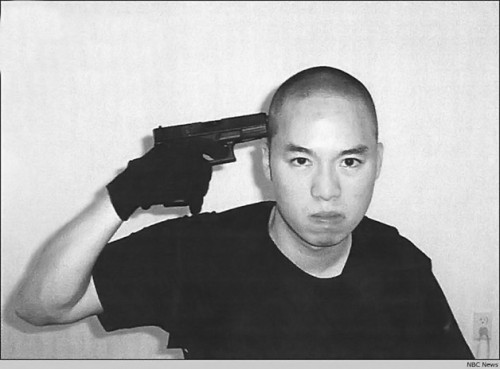

Boys Who Kill: Cho Seung-Hui

The next installment of Boys Who Kill stars Cho Seung-Hui, or Seung-Hui Cho, or Question Mark. On 16 April 2007, 4 days before the 7th anniversary of Columbine, Cho killed 32 people at Virginia Tech. First he visited West Ambler Johnston Hall, a dorm room for both boys and girls, where he killed one boy and one girl. Then he traveled to Norris Hall, a classroom building, and killed 30 more people.

Ever since Cho was taken out of his mommy’s tummy he hasn’t taken to talking. “Talk, she just him to walk,” says Cho’s great aunt about his mommy. “When I told his mother that he was a good boy, quiet but well behaved, she said she would rather have him respond to her when talked to than be good and meek.” At Virginia Tech, one of Cho’s roommates remarked, “I would see him walking to class and I would say ‘hey’ to him and he wouldn’t even look at me.” Other students concluded that he was a deaf-mute. He ate myself all by himself, and when someone offered him 10 dollars to say something, he said nothing. According to medical professionals, Cho suffered from “selective mutism.”

I, too, would prefer to be mute, and so, it seems, do other boys. Holden Caulfield dreams about being a deaf mute, and, it’s been reported by various biographers that instead of engaging in dinner table conversation, Arthur Rimbaud would just growl. Talking is terribly human — this race of creatures does in it grotesque quantities: they talk at Whole Foods, at overpriced bars, at trendy coffee shops, and, obviously, through Gmail, Gchat, texts, Facebook, Twitter, Disqus, and so on.

Cho’s contempt for normal communication distinguishes him from humans. Virginia Tech students and teachers constantly construct Cho as boy who confound expected human behavior. A professor labeled him “disturbing” and “unusual.” A student in his playwriting class said Cho “was just off, in a very creepy way.” According to Nikki Giovanni, students started skipping her poetry class due to Cho’s behavior . When Nikki told him to either cease composing sinister poems or drop her class, Cho replied, “You can’t make me.” Eventually the then head of the English Department, Lucinda Roy, tutored him privately. But even Lucinda was afraid of him. During the one-on-one tutoring appointments, Lucinda and her assistant agreed upon a code word that would prompt the assistant to summon security when uttered.

Based on this testimony, Cho is similar to a virus or a disease. No one wants to be around him; everyone is horrified of his presence. Not one to stay up into the wee hours of the morning to drink, party, and partake in sexual intercourse, Cho went to bed early and awoke early. He also played basketball alone. According to the New York Times, Cho was in a “suffocating cocoon.” (Being in a “suffocating cocoon” seems very dramatic and cosy; it also seems as if a “suffocating cocoon” would provide protection from mankind.) Virginia Tech journalism professor Roland Lazenby sums up Cho as a “shadow figure, locked in a world of willful silence.” Both Lazenby and the Times portray an incomprehensible boy who, isn’t free and liberated like Western subjects, but is held captive by a dark dangerous force. As Theresa Walsh, a girl who witnessed the killings in Norris Hall, says, “I’ve never really thought of him as a person. To me, he doesn’t have a name. He’s always been just the ‘the shooter’ or ‘the killer.'”

Cho, like Dylan, liked girls, and Cho, like Dylan, like to like girls in an incorporeal context. Rather than obtain a real-life girlfriend, Cho invented his own, a supermodel named Jelly, who resided in outer space and commuted by spaceship. At Virginia Tech, Cho would bombard girls with instant messages and take their photos without their permission. Unlike the capable prototypical straight boy, Cho’s relationships with girls were really rocky. He wasn’t smooth and suave. Some girls were so scared of him that they got the cops. But I understand why Cho would be so shaken by girls. Girls talk too much, cry too much, and have strange body parts. Yet girls, like dolls, are also very pretty, with their hair bows, baby-doll dresses, and dark eye shadow. So it’s frustrating to figure out the appropriate approach to them.

As with Dylan and Eric, Cho liked writing. Cho composed poems, plays, and novels, but no one seemed to like any of them. Nikki didn’t care for his ghastly poems, Lucinda dismissed his novel as teenage angst, and an unnamed professor summarized his plays as “very adolescent” and “silly.” Reviewing Cho’s oeuvre for Entertainment Weekly, Stephen King declared, “Cho doesn’t strike me as in the least creative. There’s no story here, except for a paranoid a–hole who went DEFCON-1. He may have been inspired by Columbine, but only because he was too dim to think up such a scenario on his own.” King’s evaluation is hostile and angry, as if he’s reviewing the writings of an archenemy.

A boy who doesn’t perceive Cho as a nemesis is Tao Lin. According to the Alt Lit hero:

If Cho Seung-Hui was in my writing class and wrote a story like: “Cho Seung-Hui woke up and picked up a knife and followed Tao Lin into the bathroom and stabbed Tao Lin in the ass and ass-raped Tao Lin, then put Tao Lin in a bag, brought Tao Lin home, and ate Tao Lin’s corpse,” I wouldn’t “report” him for counseling. I would treat the story like any other story. I would probably like the story because those are all things I have thought myself. I have thought about killing people, etc.

While Cho never wrote about killing Tao Lin, he did write violent compositions. In one play, the Hamlet-inspired Richard McBeef, the protagonist screams, curses, and issues death threats at his pedophile stepfather. The boy shoves a cereal bear down his stepfather’s throat and his mommy chases him with a chainsaw. This is quite violent, and violence is entertaining.

“A person’s writing comes from their brain. It is who they are,” explains Tao. “If a teacher censors writing or expresses ‘concern’ about a person’s writing that is the same as censoring someone’s existence or expressing ‘concern’ about the idiosyncrasies of a person’s personality.” Like John Milton, Tao sees writing as an extension of one’s being. One’s poems or plays or stories aren’t separate from their creator, they are a part of them. While studying creative writing and literature, I was invariably appalled at how the other students viewed their writing. It didn’t mean much to them; it was just something that they had to do for class. That’s not how it should be. Any literature that’s lovely literature is loaded with meaning. When Dylan composed his shorty story about a boy who kills his fellow high students, he meant it. When Cho composed his violent plays, he meant them.

As with Dylan and Eric, Cho’s victims consisted of subjects who had assimilated into the American way of life. They weren’t “off,” nor did they suffer from selective mutism. They did sketch comedy, played tennis, and survived the Holocaust. If you aim to be the star of the New York Times, blogs, the news networks, &c, then you must murder humans that are associated with Western ideology. There are large levels of violence in the Middle East. Earlier in January, a car bomb explored in Syria, killing at least 16 people. Do Western subjects care if non-Western subjects die? No. But they get awfully angry when their own are obliterated. After viewing Cho’s video manifesto, Virginia Tech journalism student Neal Tonnage scathes, “Seeing this gutless punk lay blame on society for his mental health issues makes me sick. HE KILLED A HOLOCAUST SURVIVOR!!” Would Neal have been commensurately contemptuous if Cho had a killed a Darfur survivor, a Congo survivor, or a drone attack survivor? Would the book in which Neal’s abrasiveness appears put those ordeals in all capital letters (and add two exclamation points)?

Like Dylan and Eric, Cho listened to lots of music. Dylan and Eric listened to Nine Inch Nails and KMFDM; Cho listened to Collective Soul’s “Shine” over and over. Collective Soul doesn’t seem to be as bellicose and violent as Dylan and Eric’s music, but maybe Cho heard something in the lyrics that inspired violence: “Teach me how to speak / Teach me how to share / Teach me where to go / Tell me love will be there.”

Even though Cho made a media kit, even though he sent it to NBC and acquired a lot of attention, Cho is absent of the devoted admires that Eric and Dylan possess. There haven’t been movies based off of him nor have there been tons of Tumblrs that avow their nonstop love for him. Eric and Dylan were charming, duplicitous boys. They had stage presence and moxie. Cho had none of that. Cho didn’t go to prom or have a 20-something girl interest while in high school. Yes, I would still be Cho’s boyfriend, but only because violent boys are the best. Really, though, I would much prefer to be either Eric’s or Dylan’s boyfriend. They didn’t listen to tacky 90s music or admire Nicholas Cage like Cho did. They liked Trent Reznor and David Lynch. These BFFs were “off” too, but they had the grace and sophistication to put on a somewhat presentable performance until NBK.

Stay tuned next week for the next Boys Who Kill!

Tags: boys who kill, cho seung-hui, columbine, dylan klebold, eric harris, girls, holden caulfield, lucinda roy, nikki giovanni, question mark, roland lazenby, stephen king, Tao Lin, virginia tech massacre

I agree that censorship of writing is a form of censoring the writer’s–and their potential readers’– existence. We “censor” others’ existences all the time: with laws and their enforcement, with expressions of taste and judgement, with love and grief and rage and joy, even simply by spending money.

Whether the “censorship” of another–the gardening or shaping or other recomposition of another’s existence–is in some particular case an enablement or disablement or some half-scrutable combination –– those ethical valences are a fate and a responsibility.

What’s wrong with “censorship” of, or concern about, another’s writing and personality that’s based on reasonable anticipation of consequences? What’s wrong with self-protection?

This frustrates me because Cho Seung-Hui shot and killed my friend who was not a fiction.

Just like the drone deaths and ongoing Sudanese genocide doesn’t justify the slaughter of Connecticut schoolchildren, no murder deserves another despite the pain each one breeds. Whatever, I’m certain this is the poked-in-the-salted-wound reaction you were looking for.

no it’s not

Though you (obviously) don’t have to, could you elucidate on the reaction you were looking for? A call for psychiatric reform? Means of expression regardless of mental disorders and gun show loopholes? Curious in earnest.

For those interested in the legal and moral issues facing higher education personnel involving students’ written and oral threats of violence and this incident in particular:

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/metro/documents/vatechreport.pdf

boys who kill wants no specific reaction. i’ve been encouraged to post things that i like, and that’s what i am doing (that’s what marianne moore said u should do anyways).

murderous boys are the best because murder is truthful. so is violence. from BC to AD, murder and violence have underpinned almost everything. it’s preponderantly phony for george w. bush (although i like him too) to go to v.t. and speak badly about cho’s murders when his whole presidency was based on murder and violence.

same is so in a varying degree with bill clinton. e and d’s nbk killed 13 people, but the monica lewinsky boy’s attack of sudan’s pharmaceutical has produced thousands and thousands of dead sudanesse.

based on this, it appears as if killing isn’t wrong, but killing those who in some way represent american/western culture is. representing this is average, boring, and, as pope francis points out, unchristian. the stars of the boys who kill series don’t represent this and i like that they don’t.

this shit reads like the ghost of ’90s tarantino puked all over his own dick and then tried to suck himself off. you make me really really glad i didn’t go to notre dame.

Also, in answer to this: “Do Western subjects care if non-Western subjects die?” YES. It’s not a fucking zero-sum game.

[…] his daddy got him for a Christmas present. As with the previous four boys — Eric, Dylan, Cho, Nathan, and Leopold — Kevin’s crime was influenced by literature, as Robin Hood used a […]