Interviews

Deep Enough Place: An Interview with April Ayers Lawson

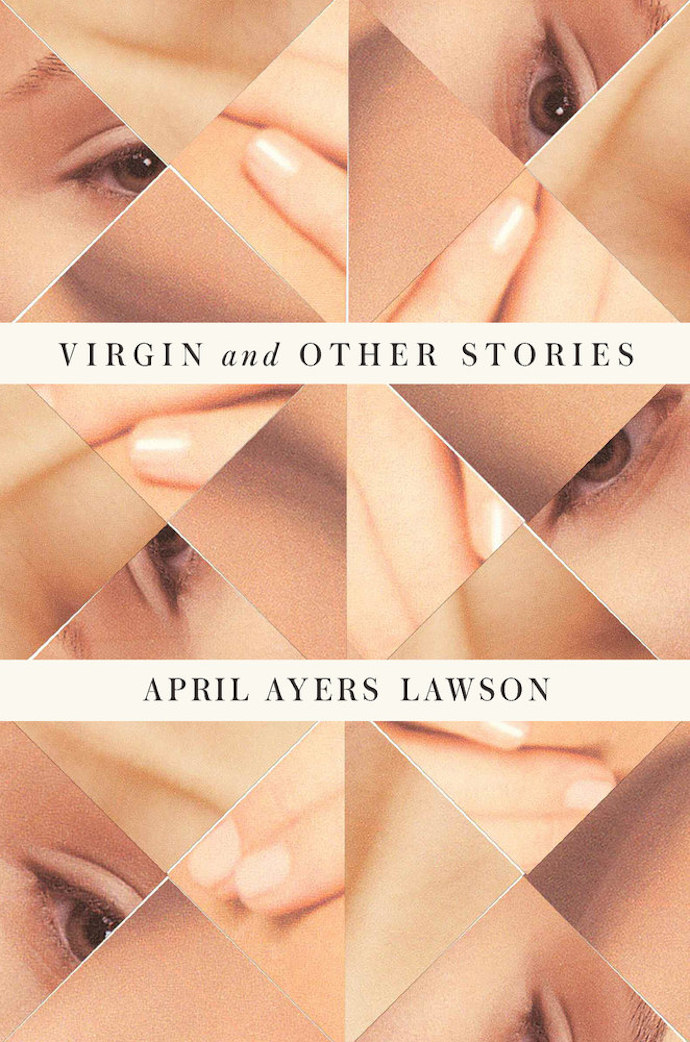

Virgin and Other Stories accomplishes what I’ve recently come to admire in the short story form. The stories are set in reality but are slightly off, something I have trouble explaining, but which April and I attempt to discuss. The writing is clean and intimate, and there’s a calmness to how the stories unfold making the tension that develops feel masterful and refreshing.

April and I spoke via e-mail – I was in Albany, New York, and April at the University of North Carolina where she is currently the 2016 Kenan Visiting Writer – about early success, dogs, writers she admires, and finally an answer to what it means to be Southern Gothic.

The title story “Virgin” was your first major publication. It won the Plimpton Prize. Can you talk a little about working on that story and then having it published to such acclaim?

The attention was wonderful but destabilizing. I felt like it was too good to be true. For example, one of the characters in the story had had breast cancer, and right around the publication time I found out I needed to have a biopsy; I figured I had breast cancer, had somehow anticipated it in creating the character, and at the time that seemed to make getting in the Paris Review make more sense to me. Like, since something I really wanted to happen had happened I would have to get ill and maybe die. I struggle with this kind of thinking. I’ve read self-help books about learning to be vulnerable to joy and happiness. Anyway, it turned out I didn’t have cancer.

That happens in publishing. Any success has a way of being undercut by a life event. I’m wondering if after writing that story you found it difficult to live up to that success. It’s been six years since you published “Virgin” and now, a full collection, which is five stories. Not a long time, but significant.

Yes. I will say that one of them is a novella and was incredibly difficult to write and transcends being a typical story. I’m not of the opinion bigger is better; Jenny Offill’s Department Of Speculation did more for me than most big novels. Juliet Escoria’s Black Cloud is amazing and, as I recall, under 150 pages. Something really happens in you when you read those books. It’s like a mystical experience (for readers who can have those; I realize DOS didn’t make sense for some people). I’m drawn towards that. But yeah, it was weird to write after the prize. Also I ended up having multiple life crises around the same time. One aspect of this had to do with stress surfacing from a past trauma. I had a nervous breakdown. For a while I couldn’t write fiction. I’d lost the mental flexibility you need to do that. It took a while for it to return. During this time I wrote a lot – wrote compulsively actually – but it was not fiction; not for publication. It was what I needed to do to keep my head above water. This is the extent to which I talk about that. Speaking generally, when I write stories I get pretty upset. I need to get upset to get to a deep enough place. So while occasionally it helps me to write when I’m upset about something in my life, more often it’s like, if I don’t feel settled I’ll resist going into the writing trance. For example, I moved recently and I wasn’t getting much done till I got a dog. My dog makes me feel settled enough to let go and focus.

So there’s a balance you need to achieve. On one hand you have to be settled enough in your life, but also anger as a kind of energy force to push the stories forward, successfully. I think what you described comes across in these stories because they are very controlled but there’s also great tension between the characters. They are about to go off the rails at any moment. I like that your dog is making you work. I’m thinking of David Foster Wallace and his dogs, Flannery tending to her peacocks, Burroughs surrounded by cats in Kansas.

Right. Well put. I think the control comes from writing into feeling out of control. The writer Josip Novakovitch once said to me that what moves a story forward is imbalance. He added, “If you run, you move forward by creating imbalance and not to fall you put your foot forward.” That sounds so simple and yet it blew my mind.

Yeah, some of us need our emotional support peacocks, so to speak. I had another dog before this one, but he died and I didn’t realize till then what his existence did for me.

You mentioned before this interview that Amie Barrodale is a friend of yours. Her stories have this feeling of imbalance, but are tightly controlled by clean prose. Same with Ottessa Moshfegh. The more I think about it, along with yourself, there’s a whole group of writers (all women, it seems) writing this way. It’s realism, for the most part, but there’s always something a bit odd. The imbalance is refreshing. For example, the structure in “Virgin” I found a bit slippery, but very real, and then the ending gets dreamy for me. The way the hallway is set-up, the child, the talk of dark and light in the rooms with the doors opening and closing. Maybe this wasn’t your intention, but I saw Jake floating there at the end, suspended.

I love both of their voices, stories. Amie’s and Ottessa’s. After I read William Wei I read it straight through again, then again, studying it in a kind of intuitive way. I see what you mean but I wouldn’t say there’s a number of women writing in the same way. A friend of mine when I first met him asked who my editor was and I said it was Emily Bell, and he said, “Are you like the others she edits that write in that style? Like Amelia Gray and Laura van den Berg?” And I responded, “Actually those writers write very differently.” To me, that’s like saying Donald Antrim and George Saunders are writing in the same style. In regard to the realism thing – well it’s kind of funny because I for a while thought of myself as being a realist. But then there was this moment when I was sort of outside myself – and maybe teaching contributed to this – seeing my writing as if someone else had done it and it hit me, Oh this is more like subtly surrealistic. Like when I write it I think I’m writing realism. Writing in the way that feels most real to me. But I’m weird. And when other people read it it’s like they see Southern Gothic or something else. But if I’m pretending to be someone else what I see is a subtle surrealism.

I love both of their voices, stories. Amie’s and Ottessa’s. After I read William Wei I read it straight through again, then again, studying it in a kind of intuitive way. I see what you mean but I wouldn’t say there’s a number of women writing in the same way. A friend of mine when I first met him asked who my editor was and I said it was Emily Bell, and he said, “Are you like the others she edits that write in that style? Like Amelia Gray and Laura van den Berg?” And I responded, “Actually those writers write very differently.” To me, that’s like saying Donald Antrim and George Saunders are writing in the same style. In regard to the realism thing – well it’s kind of funny because I for a while thought of myself as being a realist. But then there was this moment when I was sort of outside myself – and maybe teaching contributed to this – seeing my writing as if someone else had done it and it hit me, Oh this is more like subtly surrealistic. Like when I write it I think I’m writing realism. Writing in the way that feels most real to me. But I’m weird. And when other people read it it’s like they see Southern Gothic or something else. But if I’m pretending to be someone else what I see is a subtle surrealism.

Okay, so not the same style exactly. I wouldn’t group Amelia and Laura together. They seem very different to me. I do think there are a lot of women writers publishing excellent short stories. And there’s something urgent about these stories. Antrim has gone from being really weird to what you said, subtle surrealism. I know you are an admirer of his, but I don’t connect to his stories. I just can’t get into them for some reason. I wasn’t going to bring up Southern Gothic, but now you did.

I agree about the excellent stories and urgency. Blaspheme about Antrim. He had me at his story “Another Manhattan.” The sense of people in space and the gravity attaching itself to the stealing and giving of the flowers is unusual. It hits right at what fiction is/can be, in its ability to incarnate in a way I don’t think anything but “Cathedral” by Raymond Carver does. It’s a huge achievement. I think only Ben Marcus (as far as I know) has had the sense to anthologize it. Karl Ove Knausgard was wowed by it, I recall reading. I actually had not read him until I read that story. I read his novels after. Forgive me, but I think I’ve been waiting for some opportunity to go on about this. I do see how if I’d read his novels first some of the stories would seem such different and quieter things and could be disappointing if I was expecting something like in the novels. So I get what you’re saying.

April’s notebook

I’m from the deep south. I grew up near the woods with a strong Christian sense of my potential corruption. My father has a dark sense of humor that influenced the way he bonded with me and my brother, and as a family we were always watching creepy shows like Twilight Zone and X-files. As a teenager I went through a phase where I read nothing but Anne Rice. My main mentor, the writer Marjorie Sandor, grounded me in Welty and Munro (who of course is not from the American south but whose work is said to be Southern Ontario Gothic). Any resulting Southern Gothic-ness is not intentional but a result of all these influences on my psyche. I don’t write Southern Gothic. I am Southern Gothic.

Will you continue to write stories or shift to the novel?

The funny thing about publishing a short story collection as a first book with a commercial press is that people in bookselling express such surprise that it happened that it makes me feel anxious; like once after talking with a bookstore owner about it I walked out feeling as if it hadn’t actually happened because she made it sound near impossible. Another part of me though–well I like that it seems near impossible and yes, I am working on more stories. The novella form especially attracts me. Probably my need to see the entire form of something in my head–to see the patterns laid out almost flat like in a painting–keeps me limited to a length of approx. 200 pages or less, meaning if I did write a novel it would be short. Once in my MFA program a successful older writer said that if an agent or editor ever asked if you were working on a novel, always say yes. That kind of bothered me. And so now my automatic response to that question is No. I don’t even think about it. It’s kind of crazy. So far, no matter what I’m working on, when someone asks me if I’m working on a novel my automatic response is No.

————————-

Virgin and Other Stories is available from FSG on November 1, 2016.

Great interview!