Massive People

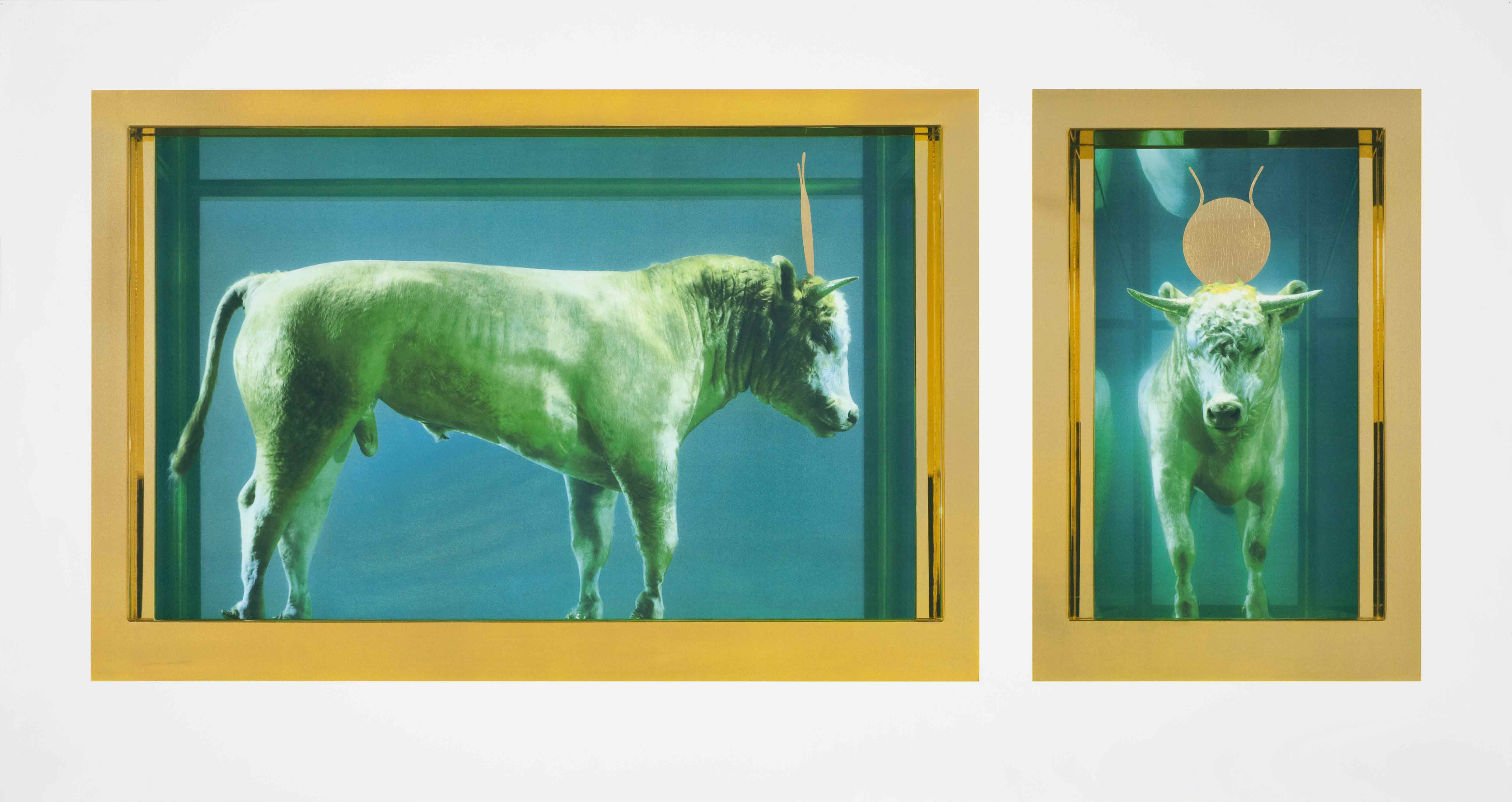

α language having a cΩω

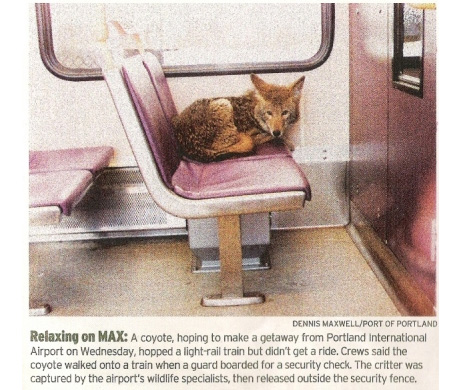

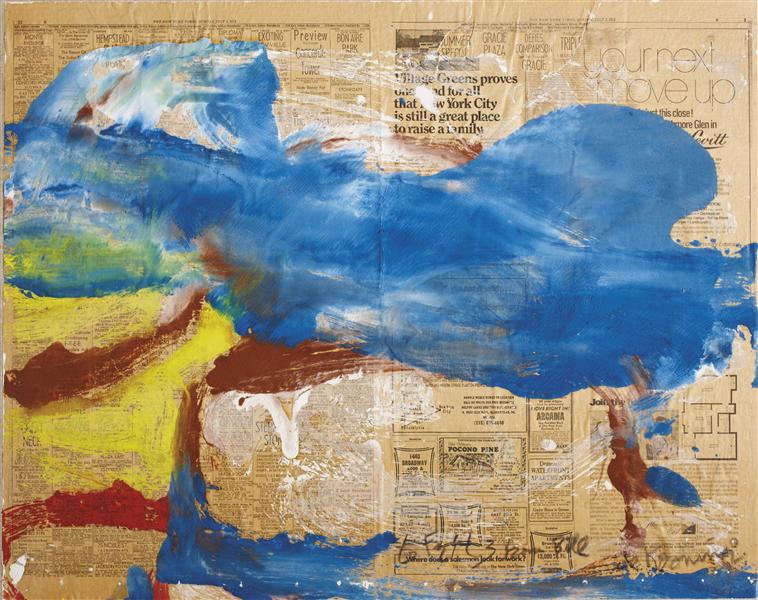

In any given landscape, B, like this, whatever is written down is beset by resemblances and whatever I hear I write down. No writing should ever be done while one is thinking about something. The newspaper on the other hand is purely temporal. It records phenomena as if they had just happened. If I have no memories of this (i.e., Plate 6), I consider this to have been the object of desire or something that is reconstructed many years after the fact.

When I look at a landscape in a novel all I see is something that I have not had the time to forget. One waits patiently for the things that have happened already. In this landscape, something I forgot (once) is about to reverse itself and become exactly what it is. You can remember someone many times but you can forget them only once.

On the front page of today’s New York Times, which I confuse with a landscape, in front of the flag, there is a photograph of an unspecified Federal building.

— Tan Lin, A Field Guide to the American Landscape: Plate 3, Side B

epilogue:

do you know this BEAUTIFUL land with its valleys and hills?

in the distance it is bounded by beautiful mountains.

it has a horizon, which is something many lands do not have.

do you know the meadows and fields of this land? do you know its peaceful houses and their peaceful inhabitants?

right in the middle of this beautiful land good people have built a factory. its low corrugated aluminum roof makes a beautiful contrast to the deciduous and coniferous forests all around. the factory is tucked into the landscape.

although there is no reason for it to be tucked away.

it could display itself. how fortunate that it stands here, in beautiful surroundings and not somewhere else, where the surroundings are not beautiful.

the factory looks as if it were part of this beautiful landscape.

it looks as if it had grown here, but no! if one looks at it more closely, one sees: good people built it.

nothing comes of nothing after all.

and good people go in and out of it.

is this good person, who goes in and out here, not our paula?

stop, good morning, paula! really, it is her. outwardly she’s hardly changed, still slim and clean. except there’s a weary undertone in her face, which one only sees however, if one looks more closely. and this wrinkle. was it there yesterday?

no, it’s a new wrinkle. and that wouldn’t be a grey hair would it? doesn’t matter, paula, just keep your chin up!

paula works here as an unskilled seamstress on the assembly line.

paula works here as an unskilled seamstress on the assembly line.

paula has finished up in the place from which brigitte set out, to get to know life. brigitte has got to know life and found her happiness in it.

paula wanted to get to know life too, now she’s getting to know the job of a semi-skilled worker in an underwear factory.

that too is a kind of life.

in the evening the people pour into the landscape, as if it belonged to them.

paula now has a small apartment, which also belongs to the factory and is therefore cheap.

paula does less than a happy person, because she is unhappy.

nevertheless her work is satisfactory, the factory is patient.

there is no trace of impatience in paula any more.

paula has come to this place to sew, not to be happy.

she could have been happy before.

now she unhappily sews foundations, brassières, corsets and panties. paula married and was ruined.

never does her gaze wander outside to a bird, a bee or a blade of grass. but in those days she was unable to value them properly.

any man can enjoy nature better than paula today.

paula sits at her sewing machine and performs her duty. she has a lot of responsibility, but no broad view and no household any more.

in the evening she drives home to her little apartment and thinks about home. paula is too tired to be discontented.

paula has no children and no husband any more, nevertheless, she is too tired to be discontented about that.

once paula had a husband and two children.

nor does the work make paula discontented.

the work makes paula apathetic.

sewing is in paula’s blood. only she let this blood out long ago, that’s why she is not as good at her work as the others. which means deductions. paula sews with all her heart, because she has no family any more, which could take up part of her heart.

now brigitte has a family and a business, which have taken up all of her heart.

it is not the very best women, who sew with all their heart.

paula is not the very best woman.

paula has already experienced her fate somewhere else. here it is over.

brigitte began her fate here. brigitte has got away.

paula was struck down. if life happens to be passing by, paula doesn’t try to speak to it. she doesn’t care to chat any more.

there goes life, paula!

but our paula is still looking for her car keys.

goodbye, and safe journey, paula.

— Elfriede Jelinek, Women as Lovers

I have come to the conclusion that much can be learned about music by devoting oneself to the mushroom. For this purpose I have recently moved to the country. Much of my time is spent poring over “field companions” on fungi. These I obtain at half price in second-hand bookshops, which latter are in some rare cases next door to shops selling dog-eared sheets of music, such an occurrence being greeted by me as irrefutable evidence that I am on the right track.

The winter for mushrooms, as for music, is a most sorry season. Only in eaves and houses where matters of temperature and humidity, and in concert halls where matters of trusteeship and box office are under constant surveillance, do the vulgar and accepted forms thrive. American commercialism has brought about a grand deterioration of the Psalliota campestris, affecting through exports even the European market. As a demanding gourmet sees but does not purchase the marketed mushroom, so a lively musician reads from time to time the announcements of concerts and stays quietly at home. If, energetically, Collybia velutipes should fruit in January, it is a rare event, and happening on it while stalking in a forest is almost beyond one’s dearest expectations, just as it is exciting in New York to note that the number of people attending a winter concert requiring the use of one’s faculties is on the upswing (1954: 129 out of 12,000,000; 1955: 136 out of 12,000,000).

In the summer, matters are different. Some three thousand different mushrooms are thriving in abundance, and right and left there are Festivals of Contemporary Music. It is to be regretted, however, that the consolidation of the acquisitions of Schoenberg and Stravinsky, currently in vogue, has not produced a single new mushroom. Mycologists are aware that in the present fungous abundance, such as it is, the dangerous Amanitas play an extraordinarily large part. Should not program chairmen, and musiclovers in general, come the warm months, display some prudence?

I was delighted last fall (for the effects of summer linger on, viz. Donaueschingen, C. D. M. I., etc.) not only to revisit in Paris my friend the composer Pierre Boulez, rue Beautreillis, but also to attend the Exposition du Champignon, rue de Buffon. A week later in Cologne, from my vantage point in a glass-encased control booth, I noticed an audience dozing off, throwing, as it were, caution to the winds, though present at a loud-speakeremitted program of Elektronische Musik. I could not help recalling the riveted attention accorded another loud-speaker, rue de Buffon, which delivered on the hour a lecture describing mortally poisonous mushrooms and means for their identification.

But enough of the contemporary musical scene; it is well known. More important is to determine what are the problems confronting the contemporary mushroom. To begin with, I propose that it should be determined which sounds further the growth of which mushrooms; whether these latter, indeed, make sounds of their own; whether the gills of certain mushrooms are employed by appropriately small-winged insects for the production of pizzicati and the tubes of the Boleti by minute burrowing ones as wind instruments; whether the spores, which in size and shape are extraordinarily various, and in number countless, do not on dropping to the earth produce gamelan-like sonorities; and finally, whether all this enterprising activity which I suspect delicately exists, could not, through technological means, be brought, amplified and magnified, into our theatres with the net result of making our entertainments more interesting.

What a boon it would be for the recording industry (now part of America’s sixth largest) if it could be shown that the performance, while at table, of an LP of Beethoven’s Quartet Opus Such-and-Such so alters the chemical nature of Amanita muscaria as to render it both digestible and delicious!

Lest I be found frivolous and light-headed and, worse, an “impurist” for having brought about the marriage of the agaric with Euterpe, observe that composers are continually mixing up music with something else. Karlheinz Stockhausen is clearly interested in music and juggling, constructing as he does “global structures,” which can be of service only when tossed in the air; while my friend Pierre Boulez, as he revealed in a recent article (Nouvelle Revue Française, November 1954), is interested in music and parentheses and italics! This combination of interests seems to me excessive in number. I prefer my own choice of the mushroom. Furthermore it is avant-garde.

I have spent many pleasant hours in the woods conducting performances of my silent piece, transcriptions, that is, for an audience of myself, since they were much longer than the popular length which I have had published. At one performance, I passed the first movement by attempting the identification of a mushroom which remained successfully unidentified. The second movement was extremely dramatic, beginning with the sounds of a buck and a doe leaping up to within ten feet of my rocky podium. The expressivity of this movement was not only dramatic but unusually sad from my point of view, for the animals were frightened simply because I was a human being. However, they left hesitatingly and fittingly within the structure of the work. The third movement was a return to the theme of the first, but with all those profound, so-well-known alterations of world feeling associated by German tradition with the A-B-A.

In the space that remains, I would like to emphasize that I am not interested in the relationships between sounds and mushrooms any more than I am in those between sounds and other sounds. These would involve an introduction of logic that is not only out of place in the world, but time-consuming. We exist in a situation demanding greater earnestness, as I can testify, since recently I was hospitalized after having cooked and eaten experimentally some Spathyema foetida, commonly known as skunk cabbage. My blood pressure went down to fifty, stomach was pumped, etc. It behooves us therefore to see each thing directly as it is, be it the sound of a tin whistle or the elegant Lepiota procera.

— John Cage, “Music Lovers’ Field Companion”

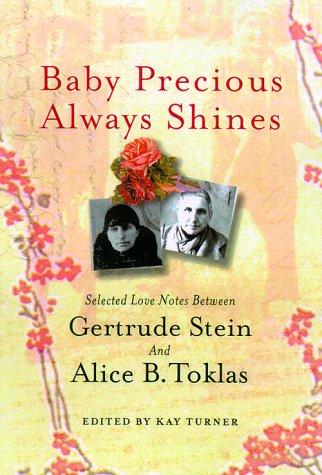

Miss Stein gets up every morning about ten and drinks some coffee, against her will. She’s always been nervous about becoming nervous and she thought coffee would make her nervous, but her doctor prescribed it. Miss Toklas, her companion, gets up at six and starts dusting and fussing around. Once she broke a fine piece of Venetian glass and cried. Miss Stein laughed and said “Hell, oh hell, hell, objects are made to be consumed like cakes, books, people.” Every morning Miss Toklas bathes and combs their French poodle, Basket, and brushes its teeth. It has its own toothbrush.

Miss Stein has an outsize bathtub that was especially made for her. A staircase had to be taken out to install it. After her bath she puts on a huge wool bathrobe and writes for a while, but she prefers to write outdoors, after she gets dressed. Especially in the Ain country, because there are rocks and cows there. Miss Stein likes to look at rocks and cows in the intervals of her writing. The two ladies drive around in their Ford till they come to a good spot. Then Miss Stein gets out and sits on a campstool with pencil and pad, and Miss Toklas fearlessly switches a cow into her line of vision. If the cow doesn’t seem to fit in with Miss Stein’s mood, the ladies get into the car and drive on to another cow. When the great lady has an inspiration, she writes quickly, for about fifteen minutes. But often she just sits there, looking at cows and not turning a wheel.

Miss Stein always drives, and Miss Toklas rides in the back seat, squealing and jumping, for they say that Miss Stein is the worst driver in the history of automotive engineering. She takes corners fast, doesn’t put out her hand, drives on the wrong side of the street, pays no more attention to traffic signals or intersections than she does to punctuation marks, and never honks. Now and then Alice will lean over from the back seat and honk. They haven’t had any accidents. One writer who visited her had a fake wire sent to him from Paris calling him back, because he was afraid he’d be killed in the Ford.

Miss Stein spends much of her time quarrelling with friends—always about literature or painting. The quarrels are passionate ones, involving everybody, taking hours to get under way, lasting for years (like the one with Hemingway). Nobody remembers after a couple of months exactly what the quarrels are about. The maid at the Stein house in Paris has to be told every day who will be persona grata at tea—it all depends on the quarrel of the night before. Gertrude sits up late, talking, arguing, and laughing; she has a rich, deep, and warming laugh. Afterward she wakes up Alice, who goes to bed early, and they go over the talk of the whole day. Miss Stein has a photographic memory for conversation.

— The New Yorker

I tend to see pilgrimage as that form of institutionalized or symbolic anti-structure (or perhaps meta-structure) which succeeds the major initiation rites of puberty in tribal societies as the dominant historical form. It is the ordered anti-structure of patrimonial feudal systems. It is infused with voluntariness though by no means independent of structural obligatoriness. Its limen is much longer than that of initiation rites (in the sense that a long journey to a most sacred place used to take many months or years), and it breeds new types of secular liminality and communitas. The connections between pilgrimages, fairs or fiestas, and extensive marketing systems will be discussed later in the chapter. The influence of pilgrimage extends into literature, not only in works with direct reference to it, such as Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, and even Kipling’s Kim, but also the numerous “quest” or “wayfaring tales,” in which the hero or heroine goes on a long journey to find out who he or she really is outside “structure”—recently D.H. Larence, Joseph Conrad, and Patrick White provide examples of this genre. Even 2001 has something of this pilgrimage character, with a Mecca-like “black stone” in outer space, near Jupiter, largest of the peripheral planets.

As the pilgrim moves away from his structural involvements at home his route becomes increasingly sacralized at one level and increasingly secularized at another. He meets with more shrines and sacred objects as he advances, but he also encounters more real dangers such as bandits and robbers, he has to pay attention to the need to survive and often to earn money for transportation, and he comes across markets and fairs, especially at the end of his quest, where the shrine is flanked by the bazaar and by the fun fair. But all these things are more contractual, more associational, more volitional, more replete with the novel and the unexpected, fuller of possibilites of communitas, as secular fellowship and comradeship and sacred communion, than anything he has known at home. And the world becomes a bigger place. He completes the paradox of the Middle Ages that it was at once more cosmopolitan and more localized than either tribal or capitalist society.

The topography of certain traditional African societies, topography defined as the representing of certain ritual features of the cultural landscapes on maps, is important to this study. In many ways my methology is Durkheimian; one way is that I begin a study by regarding social facts or collective representations, like the ideas, values, and material expressions associated with pilgrimages, as being, in a sense, like things. Just as a physical scientist looks at the physical world as an unknown but ultimately knowable reality, so the sociologist or social anthropologist must approach the phenomena of society and culture in a similar spirit: he must suspend his own feelings and judgments about social facts at the beginning of an investigation and rely upon his observations, and in some cases, experiment with them before he can say anything about them. As Durkeim has said, a thing is whatever imposes itself upon the observer. To treat phenomena as things is to treat them as data which are independent from the knowing subject. To know a social thing the observer, at least at first, cannot fall back upon introspection; he cannot come to know its nature and origin by seeking it from within himself. He must in his first approach go outside himself and come to know that thing through objective observation. But after collecting and analyzing the demographic, ecological, and topographic facts, I would go beyond Durkheim’s view in laying stess, as Znaniecki does, not only on rules, precepts, codes, beliefs, and so on, in the abstract, but also on personal documents which give the viewpoint of the actors, or on their own explanations and interpretations of the phenomena. These would constitute a further set of social facts. So too would one’s own feelings and thoughts as an observer and as participant.

Anthropologists have sometimes noted that in certain societies a ritual topography, a distribution in space of permanent sacred sites, coexists and is, as it were, polarized with a political one. Thus, among the Shilluk of the Sudanese Republic, E.E. Evans-Pritchard has shown how a system of ritual localities becomes visible and relevant on major national rites of passage such as the funerary and installation ceremonies of kings. These ritual sites and territorial divisions do not precisely coincide with major policial centers and divisions such as the national capital, provinces and provincial capitals, and villages headed by aristocrats (The Divine Kingship of the Shilluk of the Nilotic Sudan, 1948:23-24). Meyer Fortes has gone further, and uses the overlapping transparent diagrams so familiar to generations of anthropology students in his book, The Dynamics of Clanship among the Tallensi, (1945:109), to show how Tale clans or maximal lineages are linked by different sets of ties in dominantly political and dominantly ritual situations. He shows, too, how earth shrines are located within them. Moreover, in the ritual field itself certain shrines have become pilgrimage centers for non-Talis, many of whom come from as far away as the Gulf coast of West Africa, a journey of several hundred miles. G. Kingsley Garbett has suggested, following Gelfand and Abrams, how, underlying the divisions between relatively autonomous Shone chiefdoms in Rhodesia, there still exists a set of connections between spirit mediums who are believed to be the mouthpieces of ancient chiefs of the Monomatapa royal dynasty (“Religious Aspects of Political Succession among the Valley Kroekore,” 1963; passim). Whether this system of ritual linkages—and it was a system since it was partially reactivated to organize unified resistance to the British in the Shona Rebellion—was itself the attenuated and symbolic successor of a once fully operational political system, as some scholars such as Terence Ranger and J. Daneels suppose, it nevertheless continues to operate, like the Tale cults of the earth and External Boxar, as a symbol of “common interests and common values” (Fortes, 1945:81). These earth shrines, too, were closely identified with the indigenous people of the region, the Talis, rather than with the incoming Namoos. I do not propose to multiply citations here, but would like to point to the further distinction made in many west and central African societies between ancestral cults and cults of the earth, and between political rituals organized by political leaders of conquering invaders and fertility rituals retained in the control of indigenous priests. Each of these opposed types of cults tends to be focused on different types of shrines situated in different localities, resulting in overlapping and interpenetrating fields of ritual relations, each of which may or may not be hierarchically structured. To simplify a complex situation, it might be said that ancestral and political cults and their local embodiments tend to represent crucial power divisions and classificatory distinctions within and among politically discrete groups, while earth and fertility cults represent ritual bonds between those groups, and even, as in the case of the Tallensi, tendencies toward still wider bonding. The first type stresses exclusiveness, the second inclusiveness. The first emphasizes selfish and sectional interests and conflict over them; the second, disinterestedness and shared values. In studies of African cults of the first type, we find frequent reference to such topics as lineage segmentation, local history, factional conflict, and witchcraft. In cults of the second type, the accent is laid on common ideals and values, and, where there has been misfortune, on the guilt and responsibility of all rather than the culpability of individuals or factions. In cases of homicide, for example, in may parts of West Africa, the whole land may be purified by an earth priest.

— Victor Turner, “Social Dramas and Ritual Metaphors”

In New Delhi, rhesus monkeys roam the streets in droves searching for food. They scale trees, fences and even buildings, climb on the subways and sneak into homes, offices an even police stations. The problem has gotten so bad the city has even trained large black-faced langur apes to scare off the smaller monkeys from approaching government buildings.

Coyotes, black bears and peregrine falcons have also been known to set up shop in cities. Bears love dumpster diving, and it sometimes takes as much as rubber bullets and pepper spray to shoo them for good. Coyotes are clever and adaptable and, like raccoons, can often be found lazily patrolling cities and suburbs. Falcons have been found roosting in the skyscrapers of New York, and have been known to scare pedestrians while swooping to catch prey at speeds of up to 200 miles per hour.

— Urbanist

Lucy Church add added that a very large house was built with small rooms. This was because it had been built one hundred years ago and even so.

Lucy Church was with a name and Lucy Church and with a name a name and allowed. Peaches are yellow or crimson and apples are green or red and pears hang like pears and then it is said of them that there is more fruit than there was but not more in addition.

Very well I thank you and as to a cloud they say it is on the mountain but a mountain is not a mountain if there is pasture to repeat that a mountain is not a mountain if there is pasture. To repeat that a mountain is not a mountain if there is a mountain which has a pasture on it, which has pasture on it.

Lucy Church made many many many come to be to stay and stand and having said Lamartine all is said.

Having said Lamartine all is said in respect to the best direction to be given to be comfortably left to heaven. Comfortably left. To heaven. Lamartine and questioning, now there has been a change even within three years there has been a change within three years there has been a change now they do not begin with them there has been this change within these three years there has been this change.

Lucy Church made her sister be named Frances Church, the sister was older and had been named Frances Church. She was prepared to be here and she was here and this was a comfort and might be very well and easily pleased. Lucy Church was seen in the distance between two hills and not a long distance from Yenne but slightly higher and could be easily seen to be Lucy Church Lucy Church Pagoda and it is with some difficulty that not being remembered Lucy Pagoda could be confounded with Yvonne Pagoda at one time. Yvonne Pagoda being forgotten could be remembered with difficulty until if it happened that they were there it would be very charming to see Yvonne Pagoda stand and not pass and surrounded and surrounded and surrounded as much as is indeed with it at a distance. Yvonne Pagoda is her name. Just the same.

— Gertrude Stein, Lucy Church Amiably

— Willem de Kooning

Or we were promenading The Enormous Room after supper—the evening promenade in the cour having been officially eliminated owing to the darkness and the cold of the autumn twilight—and through the windows the dull bloating colours of sunset pouring faintly; and the Count stops dead in his tracks and regards the sunset without speaking for a number of seconds. Then—”it’s glorious, isn’t it?” he asks quietly. I say “Glorious indeed.” He resumes his walk with a sigh, and I accompany him. “Ce n’est pas difficile à peindre, un coucher du soleil, it’s not hard” he remarks gently. “NO?” I say with deference. “Not hard a bit” the Count says beginning to use his hands. “You only need three colours, you know. Very simple.” “Which colours are they” I inquire ignorantly. “Why, you know of course” he says surprised. “Burnt sienna, cadmium yellow, and—er—there! I can’t think of it. I know it as well as I know my own face. So do you. Well, that’s stupid of me.”

Or, his worn eyes dwelling benignantly upon my duffle-bag, he warns me (in a low voice) of Prussian Blue.

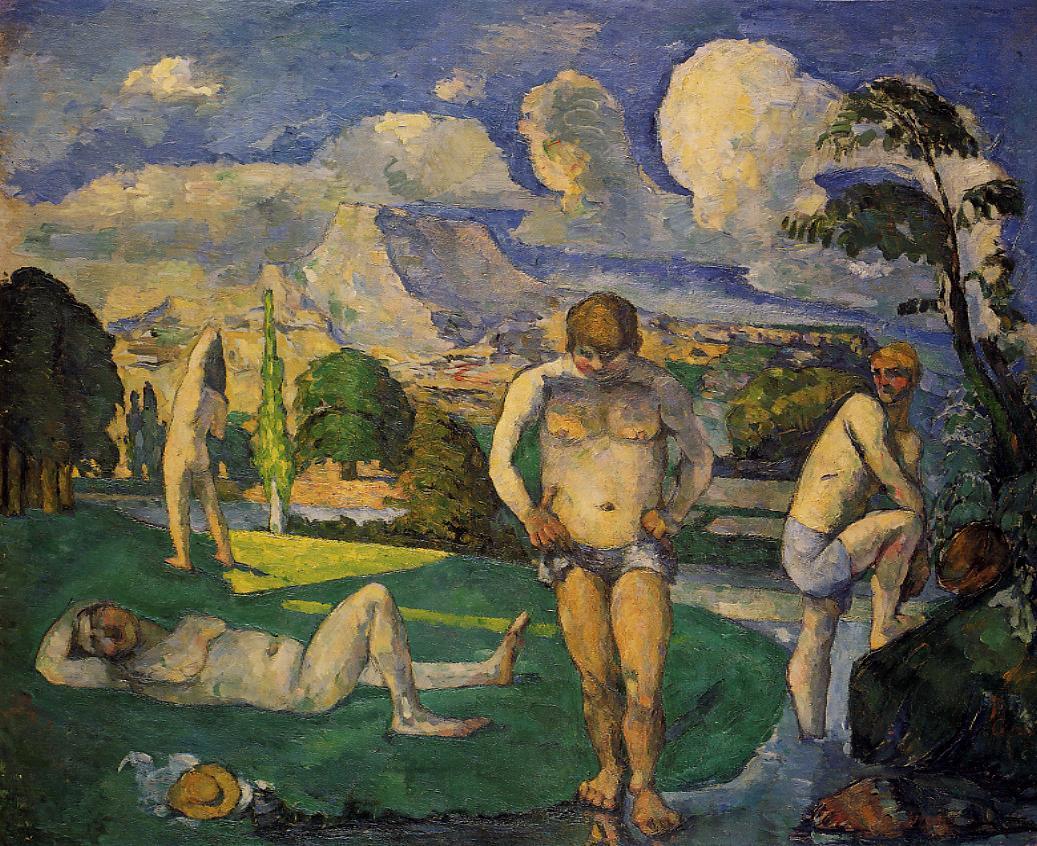

“Did you notice the portrait hanging in the bureau of the Surveillant?” Count Bragard inquired one day. “That’s a pretty piece of work, Mr. Cummings. Notice it when you get a chance. The green mustache, particularly fine. School of Cézanne.”—”Really?” I said in surprise.—”Yes, indeed” Count Bragard said, extracting his tiredlooking hands from his tiredlooking trousers with a cultured gesture. “Fine young fellow painted that, I knew him. Disciple of the master. Very creditable piece of work.”—”Did you ever see Cézanne?” I ventured.—”Bless you, yes, scores of times” he answered almost pityingly.—”What did he look like” I asked, with great curiosity.—”Look like? His appearance, you mean?” Count Bragard seemed at a loss. “Why he was not extraordinary looking. I don’t know how you could describe him. Very difficult in English. But you know a phrase we have in French, ‘l’air pesant’; I don’t think there’s anything in English for it; it avait l’air pesant, Cézanne, if you know what I mean.

—E.E. Cummings, The Enormous Room

— Amazon

Stein said do have a cow. It’s good for you to. Have a calf in the sow. Fry it at a yellow temperature. Pink its eyes with frosting while they cool. So it runs. Like drizzled teardrops.

Say the words Phoenician phonetician three no four times fast.

Say the words Phoenician phonetician three no four times fast.

The fax was invented a decade before the telephōnē. Facts.

Phoenicians considered the ox the most important thing in the world. They named it aleph, which became alpha (cock your head right up there, note the horns), our a, first letter of the west, which suspiciously rhymes with best (both German). Plutarch said α is the first thing a child utters, because it requires no motion of the tongue. The laziest bit of language. A mountain with a pasture. Tethered to the Greek álphō, “to invent.” To invent the alphabet. β means “house.” In finance it is “a measure of investment portfolio risk.” To βuy or not.

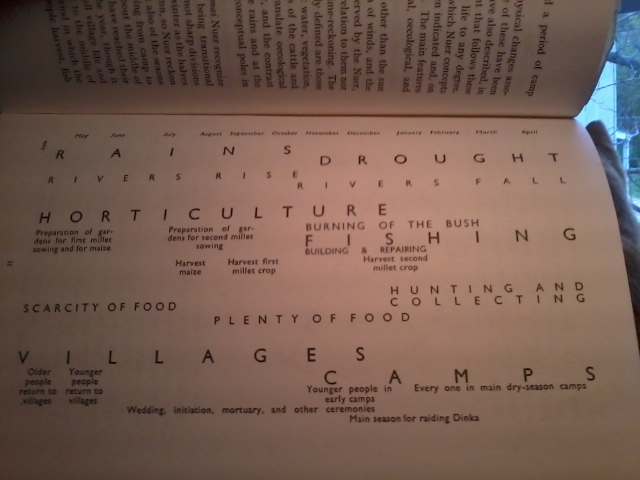

The Nuer men take the name of their favorite ox. When the ox dies they eat it and pick a new favorite ox, reborn as one is with a new nom de plum. The Nuer women become “men” if they are the oldest remaining member of a family, taking the name of their favorite ox. They become the father of their brothers and sisters. The alpha of their family. Their herd. A set of horns to hold or tassel. The Nuer equate cattle with both happiness and death. According to Evans-Pritchard, they say “more people have died for the sake of a cow than for any other cause.”

— E.E. Evans-Pritchard, The Nuer

Tags: a click anywhere takes you somewhere unless it's nowhere, Cage, Cezanne, cummings, de Kooning, elfriede jelinek, evans-pritchard, hirst, jesse & michelle, rembrandt, stein, tan lin, to have a cow or not to have a cow is not even a question, victor turner, α landscape having a cow

Yes!

“[A discussion of] the relationships […] between sounds and sounds […] would involve an introduction of logic that is […] out of place in the world[.] It behooves us […] to see each thing directly as it is[.]” –Cage

Sounds as they are heard are “directly” related to other sounds. Cage is being perhaps a competent Buddhist, but certainly a humorously mischievously bad phenomenologist.

—

“the whole land may be purified” –Turner

—

l’air pesant = ‘weighty manner’? ‘air of gravity’? ‘serious mien/carriage/bearing’?

I once wondered about the afterlife discussions between the ‘How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare’ hare and ‘The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living’ shark. My friend prayed, ‘Can they just be sitting in rocking chairs staring out at the [ [ landscape ] ] ?’