Random

Art, Crime, Beauty, Murder

To approach. To peek through. To see Marcel Duchamp’s final contribution, “Etant donnés,” is to confront the intersection of art and crime and beauty and murder.

Remember what Poe said in “The Philosophy of Composition“:

I asked myself—“Of all melancholy topics, what, according to the universal understanding of mankind, is the most melancholy?” Death—was the obvious reply. “And when,” I said, “is this most melancholy of topics most poetical?” From what I have already explained at some length, the answer, here also, is obvious—“When it most closely allies itself to Beauty: the death, then, of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world.

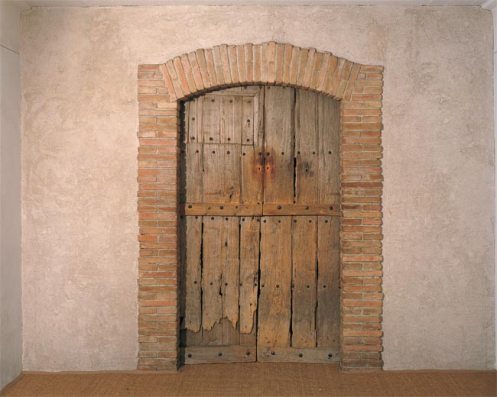

Here is the threshold:

Here is the observer:

And here is the observed….

BEWARE…NSFW…GRAPHIC VIOLENCE…enter this post at your own risk:

Murder’s aftermath.

The inspiration for the Black Dahlia murder? Perhaps.

As Jean-Michel Rabaté demonstrates in his book Given: 1° Art 2° Crime: Modernity, Murder and Mass Culture, many are the links between avant-garde art and the aesthetics of crime.

Since Ovid, at least, we have considered the role of nature imitating art:

There was a valley there called Gargaphie, dense with pine trees and sharp cypresses, sacred to Diana of the high-girded tunic, where, in the depths, there is a wooded cave, not fashioned by art. But ingenious nature had imitated art. She had made a natural arch out of native pumice and porous tufa. On the right, a spring of bright clear water murmured into a widening pool, enclosed by grassy banks. Here the woodland goddess, weary from the chase, would bathe her virgin limbs in the crystal liquid.

(Metamorphoses, Book III)

Echoed centuries later by Kant in the 45th section of The Critique of Judgement:

“Nature is beautiful because it looks like Art.”

And then echoed again by Oscar Wilde in his dialogic text “The Decay of Lying,” where he writes, amongst other gems:

“Life imitates art far more than Art imitates life.”

In other words, culture shapes the individual more than the individual shapes culture. That’s one idea, at least. Helps when playing the blame game (I & II).

In literature, we find evidence of a certain proclivity for aestheticizing crime, violence, murder. In 1827 & 1839, Thomas De Quincey actually wrote a pair of essays entitled “On Murder Considered As One of the Fine Arts,” which contains a suggestion for how we might and why we should consider seriously that most gruesome act as beautiful:

When a murder is in the paulo-post-futurum tense — not done, not even (according to modern purism) being done, but only going to be done — and a rumor of it comes to our ears, by all means let us treat it morally. But suppose it over and done, and that you can say of it, Τετελεσται, It is finished, or (in that adamantine molossus of Medea) Ειργασται, Done it is, it is a fait accompli; suppose the poor murdered man to be out of his pain, and the rascal that did it off like a shot nobody knows whither; suppose, lastly, that we have done our best, by putting out our legs, to trip up the fellow in his flight, but all to no purpose — “abiit, evasit, excessit, erupit,” etc. — why, then, I say, what’s the use of any more virtue? Enough has been given to morality; now comes the turn of Taste and the Fine Arts. A sad thing it was, no doubt, very sad; but we can’t mend it. Therefore let us make the best of a bad matter; and, as it is impossible to hammer anything out of it for moral purpose, let us treat it aesthetically, and see if it will turn to account in that way.

A provocative assertion, no doubt. One you can test for yourself by considering the actual crime scene photos of the Black Dahlia murder:

Or by considering the crime scene photographs of the Charles Manson murders:

Or by considering the self-murder of Evelyn McHale, who leapt to her death from the observation deck of the Empire State Building on May 1, 1947. Photographer Robert Wiles took a photo of McHale a few minutes after her death, and a few weeks later the photo ran as the “Picture of the Week” in LIFE magazine:

Returning to literature, Elisabeth Bronfen wrote an interesting book called Over her dead body: death, femininity and the aesthetic (Manchester University Press, 1992). In the preface, she writes:

Representations of death in art are so pleasing, it seems, because they occur in a realm clearly delineated as not life, or not real, even as they refer to the basic fact of life we know but choose not to acknowledge too overtly. They delight because we are confronted with death, yet it is the death of the other. We experience death by proxy. In the aesthetic enactment, we have a situation impossible in life, namely that we die with another and return to the living.

Obviously, Bronfen’s claim is complicated when considering images of actual death rather than staged images of death: the difference between the last few images above and Duchamp’s “Etant donnés’ or an image from Pascal Laugier’s film Martyrs, for example:

But the boundary between art and nature, or actual and staged, fluctuates flows and feeds back and forth. Both produce and are produced by the other. Crime begets art as Art begets crime. Murder begets beauty as Beauty begets murder.

So when McSweeney suggests that “Art and Crime are both limit experiences,” we should consider what limit these experiences represent or explore.

And let us not overlook the role of gender in this conversation. According to the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women, “Globally, up to six out of every ten women experience physical and/or sexual violence in their lifetime.”

Call me presumptuous, but I seriously doubt those 6 out of 10 women would agree with Poe’s assertion that “the death, then, of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world.” But then again…

This week, I taught Kathy Acker’s Blood and Guts in Highschool to a group of undergraduates. Incest and rape and torture and violence play prominently throughout it. I had assumed that students would be shocked or offended, and some of them were, but comparing it to the reaction I received last summer when I taught what I consider an equally violent text (William Burroughs’s The Soft Machine), I was genuinely surprised that it didn’t raise the same level of visceral reaction. I mean, last summer I had students who talked about how the Burroughs book made them physically ill. The predominant reaction to the Acker book was different. Students disliked what they considered to be its gratuitousness. “Every page had the F-word on it.” or “I thought she could have gotten her point across without being so vulgar.” If I’m remembering correctly, none of the female students commented about the real world implications of violence against women. None of the female students shared Acker’s anger or outrage at a male dominated cultural machine that continually reproduces the link between beauty and violence, art and crime.

All of this seems worth thinking about.

I read Nelson’s book a while ago. Compelling, a really well asserted argument. And I remember the book also being a very well designed being.

“All of this seems worth thinking about.” Indeed, this is a fabulous post that I’ll forward to others for due consideration. Thanks!

I was thinking about something like this after reading Sofi Oksanen’s Purge. It is so provocatively violent – mostly sexual violence – that I felt quite ill after it, as I did after reading American Psycho (that old chestnut – sure it’s been talked about enough).

Purge, operates somewhat within the thriller genre, and I wonder what the difference is between avant garde or ‘literary fiction’ murder/graphic attack/ and the corpse(s) or exposed and violated bodies in a thriller, especially when the lines seem somewhat blurred between the styles.

Is it possible to say of avant garde deaths that they, like thriller deaths, are trying in some way to bring the reader towards culpability/collusion with violence? Some modification of Bronfen’s argument: Despite the aesthetics (of whichever genre), isn’t it the point that we are not just observers when we read, but create the scenes in our minds, getting right down in every stab wound? It’s more visceral isn’t it? Even sometimes with painful empathy – even as the writer tries to guide our experiences into the channels they prefer.

I’m not sure. At any rate, I’m going to stick to the drawing room pieces for a while until I recover from this swoon.

Of the “boundaries” in this tangle of tangents, the one that leaped out at me most is the responsibility boundary: what aspect or portion of this “art” thing led to this (audience) act?

If the argument is that ‘there’s absolutely no connection between (say) a song and the actions its listeners take, even – but not limited to – those that those listeners identify as having been inspired by that song’-

-well, then why make music (in this case) at all? – only to get (somewhat monetized) credit for inspiring rainbows and unicorns–and the rest is ‘free will’??

Plato, most famously in Book X of The Republic, takes an opposing side–with superb and (therefore?) largely unread irony: artists are responsible. Art is dangerous. –just as words like “Fire!” and “nigger” and “safe if used as directed” are dangerous.

I think Burroughs, for example, thinks that Plato is right about this – and wants Plato to be right. Me, too.

That fucking picture of Roman Polanski…

“culture shapes the individual more than the individual shapes culture.”

my question is, who makes culture? do people not produce/re-produce culture all the time, at every level? (as a deleuzian, wouldn’t you think the opposite of the claim you made…that the shape of something precedes the event/encounter??) are we not always interacting, reinterpreting, reshaping, and producing culture all the time? also: what culture? culture is not fixed or transhistorical or globally homogenous, nor does it operate in the same way for every person. it varies from geographic location, religious/political affiliation, time, etc. the danger of these abstract claims abt culture, especially when you bring “nature” into the debate, is that you naturalize and extend a set of temporally, historically, and geographically situated set of values. is it a cultural impossibility that i do not derive pleasure from images of violence against women? the goal should be to de-naturalize/unlearn domination culture, not naturalize its existence and absolve everyone of responsibility because “we didn’t make it.” it’s true that nobody is born in a vacuum and normativized value influence what we find “pleasurable”–but we do re-make it every time we reproduce those values, and we will continue to unless we actively seek to un-make it.

surely, the united states has historically been dominated by a culture of racism up to the present day. i personally would find it pointless to ponder the aesthetics of blackface unless it was accompanied by an intention to unmake the culture of racism. i certainly wouldn’t want to claim that whites were just acting “naturally” even though they were acting in accordance with dominator culture, or uncritically produce images of blackface out of some “artistic” desire to push the “limits.” but also, i am reluctant to claim dominator culture as my own, and when dominator culture is elevated to the level of nature, it becomes a tactic to hold it in place and reproduce it as the norm.

danielle p wrote on montevideyo (http://www.montevidayo.com/?p=1601):

“There are a lot of us feminists who enjoy fashion, objectification of

the female form, violent images even, etc. not just as a guilty

pleasure, or in small doses when it’s done thoughtfully or with complex

aims, but largely in the way we were culturally trained to do.”

who is the “we” and what culture are we talking abt?

certainly there are women that enjoy slashers, and there are probably just as many women who don’t. but the rhetorical strategy used here is one of extension and normalization. as if culture were a fixed algorithm that always generates the same exactly result every time data is entered.

why didn’t the students react to acker? they were probably bored. over-saturation of violence/obscenity just flattens it and nullifies its ability to shock. maybe they were desensitized after being bludgeoned…?

“what’s the use of any more virtue? Enough has been given to morality; now comes the turn of Taste and the Fine Arts.” i actually dont give a shit abt fine Arts or Taste. the implicit claim is, let us think about aesthetics and not people. let us elevate Art.

I think of Dennis Cooper and Maggie Nelson writing about/talking about Sade… how quickly violence loses its evolutionary power to affect (negatively; shock, repulse, send up anti-reward signals, etc), how quickly it becomes boring, repetitive, comical, formal, abstract. It’s a tricky thing. Violence, sex, all of the sights that incite our dopaminergic response should be carefully placed & rendered, safe to say. In art and in media.

Jackie, your reaction is strange to me. I’m not sure I understand your reaction.

You do realize that when I wrote “culture shapes the individual more than the individual shapes culture” that I was not making a claim, right? I was rephrasing the Wilde quote.

The claim I did make is more of an observation than a claim, but it came later; it was this: “the boundary between art and nature, or actual and staged, fluctuates flows and feeds back and forth.” That’s pretty Deleuzian, no?

Yeah, it’s an interesting thread. I’m curious to also check out the Hodel book on the subject.

also, i don’t think that we should “deny” when we take pleasure in something that is “problematic”–the problem arises when people try to dislodge a work from the living social context, valorize Art/Aesthetics above also else, justify/naturalize a certain position/perspective (i.e. pleasure from violence).

for example, some people feel bad about liking henry miller b/c he’s a sexist asshole, and sometimes there is a tendency to try to redeem and absolves things/people we likes to relieve the sense of guilt. instead of try to make an argument that henry miller or the surrealists or bukowski or whoever is not sexist (or better yet, they’re a feminist)–why not admit to liking something that has aspects that are problematic and go from there? the tendency for some to create elaborates justifications for things that they feel guilty for is unproductive and just as reactionary as the moralists.

i read Sade recently and found it laughable repetitive and insanely moralizing in terms of its anti-morality. i was so bored, in fact, that i was tempted to put it down because i felt like i was getting absolutely nothing out of it at a certain point.

I’m excited to get hold of Maggie Nelson’s new book. I read that recent excerpt in LA Review (was it?) and got super enthralled with what she says therein. I’m also excited to read Marbled Swarm. Dennis confronts this intersection (art/crime/beauty/murder) in super compelling ways.

Oh wow the “Can a moral deplorable thing be pleasing in a purely aesthetic sense” thing again, our cultural memory is surely short. I will just post this in response by Jolene Tan (TRIGGER WARNING):

“Roman Polanski fed alcohol and drugs to a 13-year-old girl before vaginally and anally penetrating her while she cried and said “no”. He then left the jurisdiction to escape punishment for an act he had acknowledged committing. If those aren’t “rape” and a “flight from justice”, how do you avoid the conclusion that both of those are null sets?These events had me thinking of a longstanding complaint of mine about (of all things) a book. “Lolita” has become a byword for the idea that some little girls can quite ethically be the target of sexual advances by adults because their essential nature is one of “promiscuity” and they are therefore unrapeable. This is ironic in a particularly sickening way, because Nabokov’s novel is about the monstrous connections that may exist between acts of genius, or creations or experiences of sublime beauty, and the infliction of cruelty. The central question is whether – to borrow from Richard Rorty – “ecstasy” and “iridescence” are fundamentally detached from curiosity about and empathy for the pain of others, and what that means for those of us who pursue these things, like the paedophile Humbert Humbert, and the complicit readers (all of us) who thrill to the irresistible splendour of his language.In other words, Lolita is about, precisely, the evil of refusing to hold someone like Polanski accountable for his crime on account of his “genius”. The common perversion of this insight struck me with especial force in the face of this phalanx of famous folks closing ranks behind their own, to protect a “great” man from any consequences for the piteous and irrelevant fact that he caused real human suffering.

“Unless it can be proven to me – to me as I am now, today, with my heart and my beard, and my putrefaction – that in the infinite run it does not matter a jot that a North American girl-child named Dolores Haze had been deprived of her childhood by a maniac, unless this can be proven (and if it can, then life is a joke), I see nothing for the treatment of my misery but the melancholy and very local palliative of articulate art.”

From Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov, emphasis mine.”

After reading McSweeney’s entire post, I now have a better grasp on

her argument, though I’m not a fan of reductive rhetorical

constructions like, “x is y, and y is x.”

What most confuses me is this discussion’s timing or urgency. The ideas

feel rather familiar and Foucauldian, and it’s not so much that they lack interest, but that they don’t seem integrated thoroughly enough within a specific, contemporary social context.

As someone who has studied the Decadent and Fin Di Siecle Victorian Writers closely, I don’t need to be reminded 100+ years later that art and crime can intersect for transgressive purposes–this is old news.

yes, that’s true. it does not necessarily follow that the argument articulated is yrs.

but still, there are extreme limitations to the “flows” that you map…

“Crime begets art as Art begets crime. Murder begets beauty as Beauty begets murder.”

art may not beget crime, just as murder may not beget beauty. i am not saying that you don’t think it’s possible, but i think there is a serious need to make room for that possibility if we want to imagine other ways of being and relating to each other.

the idea that we are created by a violence culture and that we create violence still naturalizes the relationship between violence and culture by implying that they are the logical conclusions of each other.

Helen, I definitely see strong connections between “popular fiction” and “avant-garde fiction.” And I like your suggestion about certain literature trying to “bring the

reader towards culpability/collusion with violence.” It makes the role

of the reader more active, less passive. We don’t watch a crime, we

participate in a crime.

i actual have it on my desk in front me right now. it’s decent but ultimately way too cautious. mostly just “unpacking” without hard analysis.

Oh, okay. You’re making the point that it isn’t always the case that art begets crime and vice versa. That’s valid. But where those lines of flight venture away from this nexus is another conversation. I was trying to shine a light on their connection, not the possibility that they may not connect, which I presumed was a given. Where they conjoin is what was interesting me. You seem to be saying that they don’t always conjoin. I think I would agree with you. Sometimes they don’t.

The Nelson? Oh, that’s too bad. :(

“i was so bored, in fact, that i was tempted to put it down because i felt like i was getting absolutely nothing out of it at a certain point.”

Not a bad reaction to violence, right?

I agree. Wanted to love it so much (after Bluets).

The problem with Lolita is that it takes a lot more effort to understand the fact that HH is a monstrous figure behind a glorious (slipping and occasionally self-revealing) mask and that the girl ‘Lolita’ never existed than it does to read the novel, which is so wonderfully done.

Those who only know Lolita as the fiction created by Humbert Humbert, and only that third hand (warped into ‘jail bait’) have much less ability to use the narrative as a basis for seeing through the flimsy idea that geniuses should be held to a differing standard of morality.

Given that Polanski’s crimes are concealed and codified not just by his own bravado, indifference, whatever you would call it, but by many respected artists (who all work with language to erase the rough edges, so to speak), is it not easy to understand that many people have been able to forget or view him with less intensity of outrage? A multitude of Humbert Humberts…

yes…it’s very neutral and journalistic. but it is good at raising questions and fleshing out the issues…highlighting the debates without making claims about them.

There is an edition of Lolita that calls it a “wonderful love story” on

the back cover copy. I think I stared at it in the bookstore for a long

time. Still sticks with me because it is so horrible.

The discussions seem also to avoid the last Century of developments. As in… the artist is not actually a transgressor at all but a creator of cultural capital. Every modern city is covered with large abstract sculptures, “street art” has been a big business for at least 3 decades (in the 1980’s you could pay for graffiti tours of NYC or even pay someone to “mug” you in the Bronx), etc etc. We’ve all read the Situationist critiques of art, right? Or Adorno?

There is an argument to be made for the possibility of subversive practice in culture (contra the Situs and Adorno). Wu Ming are the best example of that argument. But, today, that practice does not involve transgression and crime and blood and guts and sex, at least not as far as I can see.

All of this seems like a desire to repeat the 20th Century. Not sure why one would want to do that.

So, can anyone tell me why this topic even matters, or is the point to just sound smart by stating the obvious?

I’m starting to think, more and more, that today’s writers are averse to history or historical perspective.

It guess it makes since why so many writers dislike theory and criticism–they would have to leave their precious contemporary bubbles and realize that much of what they consider “new” isn’t all that new.

I don’t understand your hostility. First you say that this conversation fails to be “integrated thoroughly enough within a specific, contemporary social context” (your comment above) — and now you’re saying that the conversation fails because it’s caught in its own “precious contemporary bubble.” It seems like you don’t know what you’re angry about, but you know you’re angry.

I would not argue with your assertion that this is all old news. In fact, I would say all news is old. I see this as a conversation. Perhaps you dislike the conversation or have little interest in it, but that does not invalidate it. I personally have no interest in a conversation about baseball — talk about old news! — but that doesn’t mean that it’s unworthy of being discussed by people who do find it an interesting topic.

Furthermore, your suggestion that any of the participants in the conversation are averse to history is unfounded. My post itself incorporates material from the early 19th century (Poe and de Quincey) up to a few years ago (Rabate & Martyrs).

I just don’t get where you’re coming from. And it’s a shame because I think you could offer a significant contribution to the conversation, yet you choose instead to be hostile. You’re smart and obviously have a strong knowledge-base from which you could draw for the purposes of engagement rather than dismissal.

I don’t understand the continued need on this site to slap the “hostility” label on any opinion that’s not expressed in a milquetoast tone. I’m not “angry,” and the routine attempts to associate passionate commentary with some sort of psychological or emotional flaw of the poster are laughable and juvenile.

Moving along to stuff that actually matters. You write:

“First you say that this conversation fails to be “integrated thoroughly

enough within a specific, contemporary social context” (your comment

above) — and now you’re saying that the conversation fails because it’s

caught in its own “precious contemporary bubble.”

I don’t see how the two contradict at all, since I used the word “integrated” to describe a topic with a well-founded historical precedent. The first quote you parsed came from a post of mine that said things like, “all this feels familiar and Foucauldian.”

And while you do name-drop historical references, everything feels tangential and jumpy (again, keyword: integration). However, I will concede that it’s probably unfair to judge your post as a fully developed essay or blogicle . I should’ve done a better job of acknowledging the medium in which the post is written (sort of like a “thinking out loud” post).

As for what I have to offer? It’s difficult to know where to begin, to be honest with you, because I have no clue what you are actually trying to say. I’m sorry if this comes off as harsh, but I can think of no better way of saying this–what are you saying here? Or, am I over-analyzing what amounts to a discussion prompt? If it’s the latter, then I do apologize. It can be difficult at times to discern the different purposes of this site’s posts.

I figure I’ll jump in here, I only sort of skimmed the discussion on this because I’m not all that interested in it, but what you bring up here interests me, and is something I have been trying to gather an opposing perspective on.

I’ve never been interested in criticism for a few reasons. First off, I can think on my own. I can come to my own conclusions on my own. I know the counter-argument to that is criticism can provide new ideas to me I never thought of, but the fact is that rarely happens, and if it does happen, it can take 20 minutes to hear about it while having a meaningful conversation with a friend instead of reading a bunch of over-inflated text, i.e. after learning about Machiavelli, I tried to read The Prince, and then I stopped reading The Prince because I thought so much of what was written was repetitious and unnecessary. Basically, to deflate my own puffery here, most criticism I’ve read is written in an inefficient manner.

I also feel that this push for an interest in criticism delineates the goal of writing. Just like any other medium of art, the goal is not to create something new. That’s because no form of art has a particular, defined goal. Five years ago, I might have read your comment and thought, “Fuck, better get more versed in criticism so I can write more original stuff,” but that would’ve tainted my work, because that means instead of writing things I like, I would’ve been writing for someone else — for you, for the critics, for all the people so hung up on breaking ground, and that means my work is disingenuous, and we all know what the people say about bullshit in writing.

The fact is, I wouldn’t care if someone called me out on something I wrote not being new. I don’t run around declaring any of my writing to be new. I do, however, declare my writing to be something I care about and something I feel is original in my own limited scope of the world. I mean, if someone told me that someone else had done it, and I didn’t know about that someone, well, shit, then it’s just sort of a cool coincidence that I had the same thoughts as an historical figure.

Looking forward to your response, if any, as you seem to be good at arguing, and your responses are always very clear.

It is pathetic to direct the violence specifically at women, that is not clandestine or pushing the envelope, it is a way to pander to the norm, and recreate it. Why not show a rapist being murdered? Why is it only “exploring the limits” when we celebrate violence against oppressed people, and never the reverse? Because it is easy to do and you are weak.

Fair response. A lot to address here (probably won’t get to it all).

First, a general point about criticism/theory: the best of it, I’d argue, tells us what we already know. It untangles, articulates, and abstracts aspects of a text and presents a complimentary and deepening dialectic to our reading (and future readings).

But, looking back, I’m not sure it’s fair to say that too many writers today are anti-theory/criticism. Rather, it’s more apt to say that too many writers today–including a strong contingent on this site–seem to think that the only or best way to respond to trauma or oppression is to “aestheticize” it. In other words, aesthetic readings seem to take precedent over historicist readings, when the two should probably inform each other more actively, and thoroughly. In fact, that’s the way it’s headed in academia.

Yet, when I look at these photographs (if you we can imagine them for a minute as fictions or poems), none of them move me at all. All but one I find rather boring and static. As Jackie Wang said, at this point in history, there’s really nothing interesting about exploring the “aesthetics of black face” if you’re not trying to undo blackface, so pictures of bloodied, murdered women that appear to merely present an “aesthetics” of murder for the sake of doing so do absolutely nothing, in my opinion, to undo violence against women. I’m not suggesting, either, that art should have a neat, tidy moral purpose–I’m just suggesting, uh, well, that I’m simply bored to death and unengaged with these photographs that don’t appear to be doing anything and/or attempting to undo their own representations, photographs that I swear I’ve seen before, even if I haven’t (and I don’t mean that in a good way–I mean, I could’ve predicted what they’d look like). That’s a problem.

As another poster pointed out on the previous thread, and as Don has pointed out here, this sort of simplistic, static, and un-dynamic aestheticizing of trauma often plays right into the hands of those in power–marketers, corporations, etc.–and leads to shallow, depth-less, uncritical fetishsizing, kitsch, novelty, etc. The common response, of course, is that people like me don’t want art that is “confrontational,” which is a cop-out because the best “quiet” and “palatable” art is certainly “confrontational.” Gwendolyn Brooks’ “Maude Martha” is just as “confrontational” as Richard Wright’s “Native Son,” and privileging one register of “confrontation” over another is highly suspicious and limiting and makes me wonder why people would even bother creating art if they’ve figured out that their way is the best way.

Hold up: who, in defending the art of Polanski’s films, defends raping a kid on any grounds?

Sure, Humbert Humbert is “deplorable”; so are Macbeth and Iago and Edmund and (Shakespeare’s) Richard Crookback, and Anse Bundren and Tom Buchanan and Robert Cohn: all “deplorable” creatures whose morally repellent actions are unveiled in ways greatly “pleasing in a[n] aesthetic sense”. (I’d argue strongly against any “purely” aesthetic anything!)

Polanski is a criminal (I guess; are the facts of his case really so undisputed and indubitable?) who’s also an artist. Pound and Celine partook politically (at least) of great crimes, and also wrote things “pleasing in a[n] aesthetic sense”.

An argument for the art of disclosing depravity is no argument for that depravity itself, nor does the depravity of an artist – her or his criminality – stand over against the work she or he releases.

The fact that morally deplorable actions can be shown so as to be pleasing to look at and even made to appear to be pleasing to do–well, art is dangerous.

–but how is attending Humbert’s ‘memoir’ with pleasure connected to letting Polanski off the hook for rape??

“Over 70 international film makers have signed a petition demanding Polanski’s immediate release, complaining that the Zurich film festival should not have been used as an excuse to arrest him, and that the poor dude will ‘face heavy consequences’ and lose his freedom should be be extradited. The French government has vowed to lobby the US for his release. Shame on all of them, quite frankly, and I’m sad to have to include one of my favourite directors, Pedro Almodovar, in there.” – Laura Woodhouse

Thanks for response. Will get to it tomorrow. I am drunk.

That sounds way more interesting than responding to my post. I need to be drunk too. I’m gonna take a break from commenting anyway.

Who is defending rape on any grounds?

Polanski made a deal with a prosecutor – a deal approved by the accuser – , which deal the prosecutor, under Nancy Grace pressure, then broke. Polanski fled. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Polanski_sexual_abuse_case

How is Polanski getting off the hook for statutory rape connected to being pleased by any of his movies or to being pleased by the novel Lolita?

If you’ve ever been robbed at gunpoint, at that moment (when you could have been shot), were you “bored”?

I think what jackie is suggesting is that what’s missing – for her – from the “violence” in Sade is: violence.

Let me argue that “criticism” is not simply, what, helpful in filling in gaps that one might have in engaging with something (like a novel) – though, while you’ve acknowledged this function, you might be giving it short shrift.

Criticism, both narrowly in a closely particular sense and more abstractly in (what’s often called) a more theoretical sense, ought, in addition to being intellectually useful, to stand or fall on artistic grounds, too: criticism is a kind of literature, and not merely a putatively objective art forensics.

Criticism isn’t a matter of having one’s thinking thought for one, but rather, of an occasion for thought – and for pleasure – on its own terms.

The topics of [violence in art] and [the possibility or threat of aestheticization] and [transgression vs. titillation] are important because thinking about them means thinking about politics in general, about the social struggle for power (and, maybe, justice).

i like this piece a lot

i think it’s cool he was working on it in secret and that it was his final piece

Google image searched “rapist getting murdered”, here’s one of the results:

The image is from this site: http://www.documentingreality.com/forum/f10/rapist-murdered-villagers-68603/

Note the violence in the comments.

Crimes against criminals are so much more interesting than crimes alone.

1) I find repellent the idea that society at large ought to accept the definition of “a fair outcome” as “what one particular prosecutor was willing to concede”. It is as if that deal settled the matter once and for all. Why should it?

2) Any argument against Polanski’s arrest is founded on the contention that Polanski’s actions do/did not deserve further consequences than he has/had suffered. How is this not a defence of rape?

(3) No articulable opinion on the Lolita connection right now.)

haha, I’m gonna have to go ahead and say that it is way more interesting. Not to take shots at this argument. I think you know that!

Anyway, yeah, I have no disagreements with what you are saying about the issues specifically regarding this post. There does seem to be a preference to “aesthiticize” human suffering on this site (I know I’m guilty) as opposed to historicize — and, I think, consequently, humanize — human suffering. The onslaught of violence threads on here this week is especially interesting in light of the Utoya shootings, which was one man murdering 85 people, and I don’t think has the same dark sexiness to it that serial killing does, which results in questions about how politics unsexifies murder, I don’t know, I’m getting into really retarded shit at this point I think, enough.

So I agree with you on that point. Confrontation doesn’t need to depend solely on violence. In fact, I’d posit that confrontation solely relies on incongruities, the same way that comedy does. That’s a whole other bag of worms though, and would be something I’d really prefer to talk about than discuss online, because constant clarification is a really important aspect of this business.

I’m more concerned about your statement regarding criticism. It seems to imply that a writer needs to be well versed in criticism to be a good writer. I know I really have no interest in criticism. I also think I’m a good writer. So I guess I just want to know what this

“It guess it makes sense why so many writers dislike theory and

criticism–they would have to leave their precious contemporary bubbles

and realize that much of what they consider ‘new’ isn’t all that new.”

means. Does that mean you believe a writer is incapable of being good if he does not like theory and criticism? This is what I’m really curious about in all of this.

(The rest of this… Idunno. In a couple of months or years someone will get tired of fetishizing death and write an essay about holding it sacred because this sort of way of thinking’ll get boring.)

That’s cool. I’m still not interested in criticism very much, but I guess different strokes for different folks.

But why would I want to read something when its purpose is only to serve positive affirmation, albeit in a pleasant sounding way? Idunno. I know novels have a tendency to do the exact same thing, but at least there’s a story, and characters, and curse words, and interesting use of spelling and punctuation.

And “occasion for thought”? Idunno. I think all the time. I don’t need a thinking aid. I don’t need a Viagra for thinking.

My biggest issue with Mr. Bomb’s statement is it implies I need to like criticism to write good stuff, an implied statement with which I strongly disagree. If I misread, or it was a miscomminique, we’ll find out soon enough I’m sure, but that’s my stance for now.

“Does that mean you believe a writer is incapable of being good if he does not like theory and criticism? This is what I’m really curious about in all of this.”

_______________

No, not at all, which is why I “edited” my original point about criticism in my subsequent post.

And, I’m not so much talking about “good” vs. “bad,” more than pointing to (what I perceive to be) an unwillingness to engage the past and “tradition.” While I have been critical of lingering Modernist legacies on this thread and others, TS Eliot’s “The Talent and Individual Tradition” sticks with me (Google it). Nevertheless, it’s worrisome when people apply Modernist tendencies to their work and discussion of others’ work without considering those tendencies in their proper historical contexts. Why is this so common amongst today’s writers?

a) the inoculating way creative writing is taught in this country, and not just at the MFA level. The craft-based, sit-in-a-circle-and-dissect-the-story-like-a-frog-approach is the staple at all levels, undergrad to grad, non-prestigious to prestigious. Students rarely discuss anything other than “craft.” New Critics from the 1930’s would love most creative writing workshops today. Under this format, it’s easy to cherry-pick past aesthetic trends/tenets without fully considering them in their proper historical contexts.

b) related to a), teachers of creative writing workshops often only give students a select few models, and rarely, if ever, ask students to engage with work from previous periods (and, if they do, there’s a lot of ahistorical cherry-picking occurring). Most of the contemporary models are also ones that are easy to teach and not too challenging.

c) related to a) and b), discussions of ideas like history, gender, what a work suggests politically, are often routinely frowned-upon. Again, John Crowe Ransom and his Vanderbilt Buddies would be extremely proud.

d) emphasis on the “small.” Cathy Day discusses this in many of her articles that critique the traditional workshop model. Students are encouraged at all times to think small. Students don’t write toward books or “big” ideas–they write toward a self-contained story that can be drafted and revised over the course of a semester and finally graded. Discussions in class never veer toward the story’s potential as part of something larger.

e) most writers under 40 came up in the system highlighted by a, b, c and d, even if they didn’t attend an MFA program. Despite differing camps–“realist” vs. “non-realist”–both often express an unwillingness to engage the past, history–basically, anything that’s not “contemporary.” Anything, too, that can’t be easily contained.

f) This has led, I’d argue, to an anti-intellectual and rather conservative strain in the contemporary lit scene (Jess Row discusses this often in his commentary) and allowed writers to use “aesthetics” as a crutch.

Let me be clear: I love discussing aesthetics, but I don’t love discussing aesthetics in some sort of echo-chamber.

I meant in terms of the posted article and how it’s framed by the writer.

That wasn’t my intention (re: your last paragraph).

I agree w/ what deadgod says here about criticism as a “kind of literature” unto itself.

Yeah, that was the main reason I responded to your post — my last paragraph, that is — so I’m satisfied.

I’m fine with that explanation of criticism, too. I guess it’s just something I’ve never taken much interest in. It happens!

It is not a new claim. I am interested in what you and deadgod understand it to imply. What is “a kind of literature”. How would we read criticism differently if we did/did not read it “as literature”. etc.

That’s cool, dude, and I feel what you’re saying with regard to MFA programs. I ran a workshop for a while, but it’s been five years since I’ve been in that kind of environment, and looking back, getting out of that shit has sort of opened my eyes about what it means to be a writer, and as a writer, for me at least, I’m more interested in writing than talking about writing, ya know? I’m not trying to get lofty or anything; just the road I chose to take.

Like I said below, my main concern had to do with the initial meaning I got out of what you said about writers and criticism. Everything else is a-ok in my book. Party on Wayne, etc. I’m a little drunk again.

I think the word “literature” can be applied widely, across disciplines and fields. It doesn’t always have to apply canonical and/or “literary” poetry or fiction.

1) Encouraging “society” either “to accept” or “[to] find repellent” anything definitively “‘fair'” is nowhere here the issue. A deal agreed to by the victim was stricken. Are the consequences – for example, to “fair outcome[s]” – of discarding plea bargaining well understood? (A relevant tangent: are the consequences of judicial and prosecutorial misconduct well understood?)

2) “Any” argument?

Perhaps the Swiss authorities were also disturbed by the legal misconduct that preceded Polanski’s flight, perhaps they took into account repeated statements by the victim (for example, that Polanski hadn’t “hurt” her), and perhaps the Swiss authorities believed that Polanski “did not deserve further consequences than he had suffered”. There; that final “found[ation]” is one of at least four “arguments”.

–and look again at that rhetorical question that ends 2): it reads as though any limits to punishment for “rape” (which would, when reached, have no “further consequences”) are a “defence of rape”. That, I find repellent.

Wise and mighty One, you know there’s no depiction of violent revenge taken against Bad Guys in popular culture. Are you some kind of Phallologocentrist of the West??

Ack! Not Spenser (of whom I’m a big fan); Sidney (of whom I’m, eh, less so).

All the Bad Guys in popular culture suffer really quick and painless deaths, and they’re almost never at the hands of the hero. I like it when the hero not only kills the Bad Guy, but also tortures him beforehand so much so that the lines of good and bad get totally fucked.

Am I phalolologoneorrehiaist? I don’t know.

Yes, sorry. Confused my S’s. Edited.

What about the ‘art exhibit’ in Bolano’s DISTANT STAR?

Or Andy Warhol’s car crash series?

Kudos to you for putting more De Quincey out there!

Well, the “purpose” of criticism is not “only to serve positive affirmation” (?), though enthusiastic proliferation – if that’s what you mean – is a function of some criticism.

As I understand the term, “criticism” is ‘methodical attention to experience’, “methodical” both logically and with empirical thoroughness. (That’s pretty general; Marx called himself, after – as I see things – Kant, a “critic” of political economy.)

Criticism is after the fact, and maybe it often feels ancillary, secondary, even parasitic and deleterious to some experience splendid with meaning and value (like a great movie). And, too often, criticism is stultified and stultifying with effort in being methodical somehow at the expense of attending whatever experience is the topic.

–but lookit: a movie (say) is worth watching. It’s worth talking about with friends. It’s worth thinking about in repose. It’s worth transforming one’s experience of it into art of one’s own. I think the value of criticism is similar to the value of the ‘original’ experience (of watching that movie) and to the other experiences (let’s say) dependent on that ‘original’ experience.

[cont.]

By “occasion”, I don’t mean “aid”; I mean “opportunity”. You went to the movie in the first place, right? So you’re already on the Viagra for perception, the leisure-time Viagra, the Viagra for thinking . . .

“Different strokes” for sure; there’s writers who are or seem to be untouched by the critical currents swirling about them at their moments in history, though not many writers, I think.

“[A]lmost never at the hands of the hero”?? That’s not the case with most of the Western, noir, spy thriller, and fantasy novels and movies I’ve enjoyed (or not). –and it’s pretty common – almost a cliche – for genre fiction to partake of the same moral ambiguities that literary fiction is supposed almost to take for granted. No?

I mean, simply, that criticism is to be written and evaluated by the criteria that any other kind of literature would be – such things as coherence, beauty of phrasing, and character development. Oh, hold up . . .

Anyway: criticism has, as a primary directive, explanation, so one asks of a piece of it that it explain. Faulkner, say, is under no such compulsion – he ‘wants’ to make sense, perhaps expositorily, but also in other ways (formally, say). Criticism is not fiction, but nor is it instruction (like a recipe) or an exposition rinsed of sentences (like a map or menu).

There are lots of kinds of “literature”. Some criteria of evaluation are common to all: coherence, elegance. Some are not categorically “literary”: character development, patterns of imagery.

I’d ask of criticism two things: that it be beautiful and that it explain itself well.

Well, yeah, in the spy movies I’ve seen the cronies are commonly seen killed at the hands of the hero, but it always seems the main guy dies in a much more unusual way the spy doesn’t approve of and doesn’t want to happen, watching in disgust at the whole event.

Those moral ambiguities I guess exist to an extent, but they’re normally lazy and not that unsettling — hero’s a womanizer, hero drinks, hero is the mischievous scamp we’re all in love. But I dunno, how many times is the hero a racist? Or makes his enemy eat his own shit, then cut his dick off, and then leave his quartered body on his family’s doorstep?

Western culture I think has this “boys will be boys” mentality that allows for some moral ambiguity to always exist with heroes. But rarely is that envelope pushed, I think. That old short story, “The Greatest Man in the World,” comes to mind.

mischievous scamp we’re all in love with*

“I think the value of criticism is similar to the value of the ‘original’

experience (of watching that movie) and to the other experiences (let’s

say) dependent on that ‘original’ experience.”

I understand that. But if I have to choose between doing this in conversation with a friend over a cup of coffee and reading about it by myself, I’m more interested in the former.

Hey, just outta curiosity: “there’s writers who are”… isn’t that a verb/subject disagreement? Shouldn’t it be there are writers? I know the British always refer to pluralized bands as a singular object, so I’m just curious if maybe it’s an over-the-seas difference.

Evelyn McHale….

“well dont we look the part/ sweetheart remembered for your art/ train those charms toward the charts… ”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_k8NR-JMajQ

I guess what I really want to know is, is it different from saying “criticism is writing”?

I think it is a little weird to use recipes and maps and menus as an example of non-literature when there are many instances where we (in general) have no problem accepting them as such, or as components thereof.

No, on my part, it’s an Americanism. I don’t think the Brits, who, as you say, say ‘the team are’/’the government are’, say ‘there’s ten guys in this pub’. It is an error, and I’m conscious of it as such when I say it anyway – with, maybe, an ‘uncritical’ collective-singular usage – , so sometimes, in a flow, I just leave it in writing. I’m never the one to carelessly split an infinitive.

Actually, is it an example of subject/verb disagreement, or verb/predicate nominative disagreement (if there is such a thing)?

The post first in reply to this one – I’ll be quick – is an example of “writing” that I’d find hard to defend as an example of “literature”.

It’s an interesting distinction; I doubt that anyone would reasonably call criticism ‘not writing’, but (I think) there are plenty of people who, emphasizing (or exaggerating) the forensic brief of criticism, would refuse to recognize a categorical responsibility or even opportunity in it to be artful or aesthetically pleasing–in a word, categorically to be “literature”.

I offered recipes, maps, and menus as kinds of “literature”, as literary things that “explain” but are not “criticism” (nor (at least putatively) “fiction”).

{

Hello,everyone,sorry take your time a min,show a good fashion stuff

website —— www (vipstores) net —— you can input on your web there,if you

do know how to do,you can click my username and you will come

our company website,maybe you will find something your like,thanks!

http://tinyurl.com/23963mg

hi christopher – yes, lots to think about. i always thought the ‘beauty’ of the duchamp was its ambiguity – has the figure been sexually assaulted or has she just had really good sex? one can’t know. it’s also hard to temporally locate – has something bad happened, or is the something bad only suggested by the viewer’s gaze. it’s hard to read her as dead since she’s holding a lantern upright.

i’m not sure what implications you’re making about Blood and Guts in High School – it’s a parody of secondwave feminism as much as it is an example of it, and it functions as well as a critique/parody of psychoanalysis, marxism, and the homosociality of the (male) avant-garde, and the ways in which all of these intellectual traditions have excluded women. it was also written thirty years ago. the sort of binaristic viewpoint (men-versus-women) that acker employs, often facetiously, was critiqued even at the time, and she’s writing directly into the opening stirrings of the feminist sex wars. acker is slippery, everything multivalent – she’s also incredibly campy and i think her sense of humor gets lost in many contemporary readings of her work. (a good analysis of the novel is here: http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/contemporary_literature/v045/45.4hawkins.pdf .)

i’m also not sure what you’re implying about your female student responses – it seems like it might have been your job as a teacher to make those connections – it is generally difficult to make any kind of feminist critique in an academic course that is not explicitly feminist, considering the ways in which these viewpoints are considerably devalued in (much) academic and youth culture. many of my students in Gender and Women’s Studies classes are quite obviously there to think critically about gender, since they signed up for the course, but can’t use the word feminist/m without a disclaimer (or a gag). i don’t know what your university demographics are, but my students have mostly been exposed to very little critical thinking about gender – and many of them just don’t *know* the (extremely harrowing) statistics on violence against women.

finally, you seem to be setting up some kind of burroughs vs. acker hierarchy – why? it’s as if you’re saying that a text that requires historical consideration and a degree of contextualization is somehow “less Art” than something that still nauseates, thirty years later – as if something written to be overtly political and specific to a time period (in this case, such that it was castigated by certain contingents of feminists and banned in germany for being “antifeminist”) is, because not apparently timeless, less effective aesthetically. this seems unproductive.

i guess i’m disappointed at the unstated and reductive implications going on in all of this. i don’t think your narration of your experience teaching B&GiHS versus The Soft Machine says much about anything related to the aesthetics of violence and how 30-yr-old feminist outrage is or is not effective – though i appreciate the conversation.

speaking of feminist outrage and violence in art, i highly recommend diane dimassa’s Hothead Paisan: Homicidal Lesbian Terrorist.

hi christopher – yes, lots to think about. i always thought the ‘beauty’ of the duchamp was its ambiguity – has the figure been sexually assaulted or has she just had really good sex? one can’t know. it’s also hard to temporally locate – has something bad happened, or is the something bad only suggested by the viewer’s gaze. it’s hard to read her as dead since she’s holding a lantern upright.

i’m not sure what implications you’re making about Blood and Guts in High School – it’s a parody of secondwave feminism as much as it is an example of it, and it functions as well as a critique/parody of psychoanalysis, marxism, and the homosociality of the (male) avant-garde, and the ways in which all of these intellectual traditions have excluded women. it was also written thirty years ago. the sort of binaristic viewpoint (men-versus-women) that acker employs, often facetiously, was critiqued even at the time, and she’s writing directly into the opening stirrings of the feminist sex wars. acker is slippery, everything multivalent – she’s also incredibly campy and i think her sense of humor gets lost in many contemporary readings of her work. (a good analysis of the novel is here: http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/contemporary_literature/v045/45.4hawkins.pdf .)

i’m also not sure what you’re implying about your female student responses – it seems like it might have been your job as a teacher to make those connections – it is generally difficult to make any kind of feminist critique in an academic course that is not explicitly feminist, considering the ways in which these viewpoints are considerably devalued in (much) academic and youth culture. many of my students in Gender and Women’s Studies classes are quite obviously there to think critically about gender, since they signed up for the course, but can’t use the word feminist/m without a disclaimer (or a gag). i don’t know what your university demographics are, but my students have mostly been exposed to very little critical thinking about gender – and many of them just don’t *know* the (extremely harrowing) statistics on violence against women.

finally, you seem to be setting up some kind of burroughs vs. acker hierarchy – why? it’s as if you’re saying that a text that requires historical consideration and a degree of contextualization is somehow “less Art” than something that still nauseates, thirty years later – as if something written to be overtly political and specific to a time period (in this case, such that it was castigated by certain contingents of feminists and banned in germany for being “antifeminist”) is, because not apparently timeless, less effective aesthetically. this seems unproductive.

i guess i’m disappointed at the unstated and reductive implications going on in all of this. i don’t think your narration of your experience teaching B&GiHS versus The Soft Machine says much about anything related to the aesthetics of violence and how 30-yr-old feminist outrage is or is not effective – though i appreciate the conversation.

speaking of feminist outrage and violence in art, i highly recommend diane dimassa’s Hothead Paisan: Homicidal Lesbian Terrorist.

hi christopher – yes, lots to think about. i always thought the ‘beauty’ of the duchamp was its ambiguity – has the figure been sexually assaulted or has she just had really good sex? one can’t know. it’s also hard to temporally locate – has something bad happened, or is the something bad only suggested by the viewer’s gaze. it’s hard to read her as dead since she’s holding a lantern upright.

i’m not sure what implications you’re making about Blood and Guts in High School – it’s a parody of secondwave feminism as much as it is an example of it, and it functions as well as a critique/parody of psychoanalysis, marxism, and the homosociality of the (male) avant-garde, and the ways in which all of these intellectual traditions have excluded women. it was also written thirty years ago. the sort of binaristic viewpoint (men-versus-women) that acker employs, often facetiously, was critiqued even at the time, and she’s writing directly into the opening stirrings of the feminist sex wars. acker is slippery, everything multivalent – she’s also incredibly campy and i think her sense of humor gets lost in many contemporary readings of her work. (a good analysis of the novel is here: http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/contemporary_literature/v045/45.4hawkins.pdf .)

i’m also not sure what you’re implying about your female student responses – it seems like it might have been your job as a teacher to make those connections – it is generally difficult to make any kind of feminist critique in an academic course that is not explicitly feminist, considering the ways in which these viewpoints are considerably devalued in (much) academic and youth culture. many of my students in Gender and Women’s Studies classes are quite obviously there to think critically about gender, since they signed up for the course, but can’t use the word feminist/m without a disclaimer (or a gag). i don’t know what your university demographics are, but my students have mostly been exposed to very little critical thinking about gender – and many of them just don’t *know* the (extremely harrowing) statistics on violence against women.

finally, you seem to be setting up some kind of burroughs vs. acker hierarchy – why? it’s as if you’re saying that a text that requires historical consideration and a degree of contextualization is somehow “less Art” than something that still nauseates, thirty years later – as if something written to be overtly political and specific to a time period (in this case, such that it was castigated by certain contingents of feminists and banned in germany for being “antifeminist”) is, because not apparently timeless, less effective aesthetically. this seems unproductive.

i guess i’m disappointed at the unstated and reductive implications going on in all of this. i don’t think your narration of your experience teaching B&GiHS versus The Soft Machine says much about anything related to the aesthetics of violence and how 30-yr-old feminist outrage is or is not effective – though i appreciate the conversation.

speaking of feminist outrage and violence in art, i highly recommend diane dimassa’s Hothead Paisan: Homicidal Lesbian Terrorist.

Hi, Megan,

Thanks for you comments.

The course I am teaching this summer is entitled “Reexamining the Body: Race & Gender in American Experimental Fiction.” I self-identify as a feminist (or, as an ally of the feminist cause), and so the entire course arises from that viewpoint.

My students were assigned two secondary readings for the Acker book. The first was Cixous’s “Laugh of the Medusa” and the other was the Hawkins piece you’ve linked to here.

Since this post wasn’t really about my class — that aspect appears at the end of the piece because it was a sort of afterthought in regards to its connection to all of this — I didn’t do a good enough job giving the details or contextualizing the situations. I certainly didn’t mean to set up a Burroughs vs. Acker hierarchy. What I was trying to imply, but should have made more clear, is that I find it disheartening that students are repulsed by Burroughs brand of sex and violence, but find Acker’s version merely gratuitous. I think there is something to this. I think it has to do with gender dynamics. Students weren’t repulsed by the violence against women, they seemed to almost accept it as “normal” with the only complaint being, “there’s just too much of it.” Of course, when discussing the two works we have another aspect in play, which is that Burroughs’s text is thick with homosexual sex and violence whereas Acker’s text is predominately heterosexual, which could also be playing into the reactions I have observed.

At any rate, I appreciate you commenting. I know you’ve written about Acker and I’m sure that you have a lot of insight to her work. I, too, love her work – that’s why I teach it!

You’re right, Kent! That’s a very interesting addition to the conversation…there’s the Life magazine photo and then there’s Warhol’s appropriation and manipulation of the photo…does it become art or was it always already art? Does Warhol transform it into art? Warhol as magician! And does our reaction shift between the Life image and the Warhol image? If so, how and why? It’s the same image!

Hi Chris,

Thanks for elaborating – I apologize for having made unfair assumptions about your points and their implications – in retrospect, a better approach would have been to simply ask the questions rather than attempting to fill them in with all my assumptions. It sounds like a really rad class, and I hope you’ll forgive my misdirected feminist outrage.

Yes, do check out the DiMassa – it’s a graphic novel (or rather a collection of the individual comics), and it’s very second-wave and incredibly violent towards men (and towards straight women who Hothead identifies as ‘spritzheads’). Many people I know relate strongly to it; many find it offense and problematic. But the framing of the violence is really interesting, especially with regard as to how Hothead’s violence is considered both a sign of mental illness, and a mode of recovery. It’s a really, really smartly constructed and unapologetic (though self-reflexive) violence fantasy.

Take care —

Megan

[…] Christopher Higgs: Art, Crime, Beauty, Murder […]

Interesting article.

George Vreeland Hill

When I last saw that Duchamp work in highschool I did not even consider the possibility that the girl is dead… she is holding up a lamp, how can a dead hand do that? I guess maybe Duchamp told you she is dead. Anyway, after the shock, I can’t see how someone else’s death can be beautiful at all unless you lose feeling for other humans. Only one’s own death and the end of suffering, but you won’t really get to appreciate that either. I guess if someone looks at death and feels beauty it is because they are getting some sort of vicarious pleasure there is no way they will ever achieve for themself. But why is it more pleasurable to see a beautiful woman dead then? Do we all want to imagine ourselves as beautiful women? Myself, I just feel sad about a murder because you can assume most people who have been killed didn’t want to be dead and that just sums up everything that is unbearable about life. oh wait there was something in American Beauty about feeling close to ‘god’ when looking at death, I guess yes, you would have to be looking at someone else and thinking entirely about yourself to feel any beauty in death.

As for just violence and rape, maybe it is an attempt to overcome what is disgusting to us. I think sociopaths find this stuff beautiful because it makes them feel powerful. A victim can sort of overcome being a victim by not feeling victimised. But again you are thinking about yourself whilst looking at someone else.

oh I apologise for sort of repeating some of the stuff already said in there about death. I must have read it with my brain half turned off. Anyway I like to think about death because it is what makes life valuable on the good days and it is the escape on the bad ones. Still confused about why a beautiful woman…