Random

Erasing de Kennedy

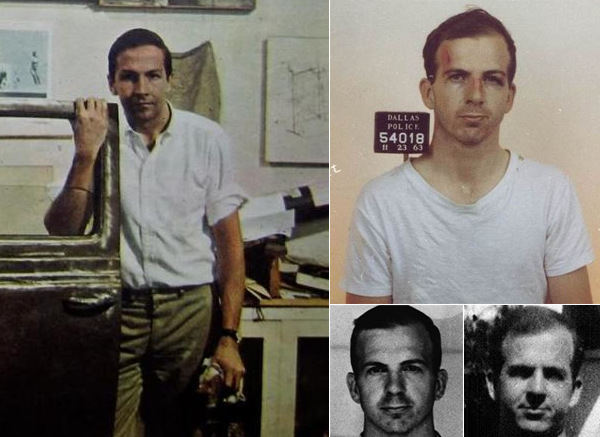

On Saturday November 23, 1963, a day after John F. Kennedy was assassinated, Dallas Police took a mugshot of the alleged shooter Lee Harvey Oswald, who would himself be shot a day later and die. It is odd how the verb “shoot” is used to describe the act of firing a bullet at someone, taking a photograph of them, and as a substitution for “shit” when expressing frustration or dismay. A conspiracy theorist (or, Gore Vidal’s wonderful “conspiracy analyst”) would say that the acute shadows formed by Oswald’s face in the infamous rifle holding photo are not consistent with the other native shadows, an impulse which implicates painting’s long forgotten task of matching light and shadows — that the latter’s convincibility, the black weary shape it finds across a cheek, legitimized the former’s absoluteness, emitted by a candle, in a dark brown room somewhere, if we are to still believe those dark brown rectangles, hanging by wires on walls, dusty on the side that matters. In 1953, Robert Rauschenberg erased a drawing by Willem de Kooning solicited by the former for the sole purpose of doing so. De Kooning caved in, as his mind would also years later from Alzheimer’s, his slow fingers pinching at sculptures which — without commentary — looked like shit, like actual pieces of literal shit on a pedestal. A true misogynist, he called them women. Like their ghost pencil marks, you can kind of see the erased drawing behind Rauschenberg’s right shoulder, or not. It was an asshole art move, which are always the best to write about. But while art grasps for history, a man, or boy, can change the world with a gun. That the right to bear arms is only the Second Amendment is telling of what has always been on American minds, though countries born of bloodshed tend to continue that path. In 1964, Rauschenberg assimilated Kennedy, presumably around the time of the one-year anniversary of his assassination, into “Retroactive I” and “Retroactive II,” two near-identical paintings only distinguishable after some amount of concentration — the light variances of the silkscreens, the purposefully similar yet inextricably unique dabs of paint — visual signs depletive of meaning, an orgy of detached signifiers, the commentary of no commentary, which might have been his entire point, so sharp, silent, and unseen, like the tip of something shiny in the air, pulled to its target over time.