Random

Primordial Theory Question

1. While any subject can be interesting to any bozo at any given time, history indicates that there are a limited number of topics that are always immediately and profoundly engaging to everyone, all the time.

2. These issues are what is referenced by the term “the human condition.”

3. They are: death, love, and the idea that I am alive and did not ask to be.

4. Death meaning, I am going to die and I don’t know when or how to behave in the face of that.

5. Love meaning, for instance, I am lonely and drawn to other humans, and yet I am human and drawn to inflicting pain.

6. I am alive and did not ask to be meaning I don’t know if you are, too, or if I made you up.

7. So my question is, what is all this other crap that people are writing?

8. In other words, how far from these issues can I take a story and still have a story that anyone will care about?

I defer to your expertise.

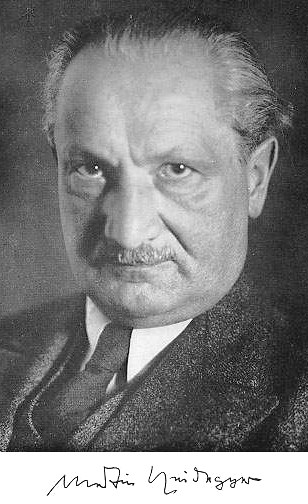

Tags: Heidegger, Theory, you are not alive

Or is this too stupid for stupid?

Or is this too stupid for stupid?

Or is this too stupid for stupid?

Well, there are a lot of ways to write about those things without having to explicitly write about those things, yes?

Like: some people invest an incredible amount of time, energy and money into building model railroads in their basements, or re-enacting the Battle of Gettysburg. And both those things probably have something to do with these other, more universal things, so if you wrote about either the model-train builder or the battle re-enactor you’d in a certain sense be writing about those larger things even though you might not be writing about those larger things directly.

Or maybe this isn’t the question you’re asking.

Well, there are a lot of ways to write about those things without having to explicitly write about those things, yes?

Like: some people invest an incredible amount of time, energy and money into building model railroads in their basements, or re-enacting the Battle of Gettysburg. And both those things probably have something to do with these other, more universal things, so if you wrote about either the model-train builder or the battle re-enactor you’d in a certain sense be writing about those larger things even though you might not be writing about those larger things directly.

Or maybe this isn’t the question you’re asking.

Well, there are a lot of ways to write about those things without having to explicitly write about those things, yes?

Like: some people invest an incredible amount of time, energy and money into building model railroads in their basements, or re-enacting the Battle of Gettysburg. And both those things probably have something to do with these other, more universal things, so if you wrote about either the model-train builder or the battle re-enactor you’d in a certain sense be writing about those larger things even though you might not be writing about those larger things directly.

Or maybe this isn’t the question you’re asking.

i think you are missing something here.

a lot of ‘entertainment’ (writing, movies, jerking off etc) is used as a distraction from love/death.

denial/ignorance can be an overwhelming drug.

the idea of ‘i did not ask to be alive’ is whine whine to me.

shut the fuck up and deal with it. life is shit. now start laughing.

so to answer question 8 i would think you could go anywhere as long as it distracts me from my mortal terror/internal loneliness.

the devil wears prada. fuck yes.

i think you are missing something here.

a lot of ‘entertainment’ (writing, movies, jerking off etc) is used as a distraction from love/death.

denial/ignorance can be an overwhelming drug.

the idea of ‘i did not ask to be alive’ is whine whine to me.

shut the fuck up and deal with it. life is shit. now start laughing.

so to answer question 8 i would think you could go anywhere as long as it distracts me from my mortal terror/internal loneliness.

the devil wears prada. fuck yes.

i think you are missing something here.

a lot of ‘entertainment’ (writing, movies, jerking off etc) is used as a distraction from love/death.

denial/ignorance can be an overwhelming drug.

the idea of ‘i did not ask to be alive’ is whine whine to me.

shut the fuck up and deal with it. life is shit. now start laughing.

so to answer question 8 i would think you could go anywhere as long as it distracts me from my mortal terror/internal loneliness.

the devil wears prada. fuck yes.

i had a professor tell me once, “Always write about what you know–you know what it’s like to be human, so write about being a human.”

The story, whatever that might be, no matter how abstract or layered, comes once you lock onto that idea.

I think that building model trains taps into something all humans can relate to. It’s not that different than writing a story, or building characters. It puts you in control of something, gives you something to cultivate and care about. Same thing with Civil War re-enactors. It allows them to be a part of something bigger than themselves. Just like a good story. A universal truth.

You can take a story as far out as possible as long as you could a sense of audience in mind. It’s once you lose that, when you’re writing to yourself and no one else, that you become unreadable. Jerking-off, I guess.

What is all this crap other people are writing? I don’t know. What crap are you referring to?

i had a professor tell me once, “Always write about what you know–you know what it’s like to be human, so write about being a human.”

The story, whatever that might be, no matter how abstract or layered, comes once you lock onto that idea.

I think that building model trains taps into something all humans can relate to. It’s not that different than writing a story, or building characters. It puts you in control of something, gives you something to cultivate and care about. Same thing with Civil War re-enactors. It allows them to be a part of something bigger than themselves. Just like a good story. A universal truth.

You can take a story as far out as possible as long as you could a sense of audience in mind. It’s once you lose that, when you’re writing to yourself and no one else, that you become unreadable. Jerking-off, I guess.

What is all this crap other people are writing? I don’t know. What crap are you referring to?

i had a professor tell me once, “Always write about what you know–you know what it’s like to be human, so write about being a human.”

The story, whatever that might be, no matter how abstract or layered, comes once you lock onto that idea.

I think that building model trains taps into something all humans can relate to. It’s not that different than writing a story, or building characters. It puts you in control of something, gives you something to cultivate and care about. Same thing with Civil War re-enactors. It allows them to be a part of something bigger than themselves. Just like a good story. A universal truth.

You can take a story as far out as possible as long as you could a sense of audience in mind. It’s once you lose that, when you’re writing to yourself and no one else, that you become unreadable. Jerking-off, I guess.

What is all this crap other people are writing? I don’t know. What crap are you referring to?

Two posts referencing jerking-off in a row. Nice.

Two posts referencing jerking-off in a row. Nice.

Two posts referencing jerking-off in a row. Nice.

Hey David Peak, I agree. While I am not that interested in model trains, if a story about model trains has as its objective correlative something more primordial, I will definitely be interested in it.

Hey David Peak, I agree. While I am not that interested in model trains, if a story about model trains has as its objective correlative something more primordial, I will definitely be interested in it.

Hey David Peak, I agree. While I am not that interested in model trains, if a story about model trains has as its objective correlative something more primordial, I will definitely be interested in it.

Jereme, I disagree with you — I think I am most distracted from these issues when I’m confronting them critically or artistically. When I entertain myself with art that doesn’t stimulate me I get anxious and think, “Oh god what am I doing, is this all there is, I’m going to sleep.” This is when I’m most attuned to the mortal terror. I like that phrase. When a book confronts me with the mortal terror, I am distracted by trying to unravel things directly related to it.

I think The Devil Wears Prada is pretty good at addressing the I didn’t ask to be alive question. I liked watching that movie (didn’t read the book) because I like thinking about what am I capable of, what do I think I’m trying hard at but not really trying at all at (like the protaganist thought she was doing until the art director guy gave her a makeover).

Jereme, I disagree with you — I think I am most distracted from these issues when I’m confronting them critically or artistically. When I entertain myself with art that doesn’t stimulate me I get anxious and think, “Oh god what am I doing, is this all there is, I’m going to sleep.” This is when I’m most attuned to the mortal terror. I like that phrase. When a book confronts me with the mortal terror, I am distracted by trying to unravel things directly related to it.

I think The Devil Wears Prada is pretty good at addressing the I didn’t ask to be alive question. I liked watching that movie (didn’t read the book) because I like thinking about what am I capable of, what do I think I’m trying hard at but not really trying at all at (like the protaganist thought she was doing until the art director guy gave her a makeover).

Jereme, I disagree with you — I think I am most distracted from these issues when I’m confronting them critically or artistically. When I entertain myself with art that doesn’t stimulate me I get anxious and think, “Oh god what am I doing, is this all there is, I’m going to sleep.” This is when I’m most attuned to the mortal terror. I like that phrase. When a book confronts me with the mortal terror, I am distracted by trying to unravel things directly related to it.

I think The Devil Wears Prada is pretty good at addressing the I didn’t ask to be alive question. I liked watching that movie (didn’t read the book) because I like thinking about what am I capable of, what do I think I’m trying hard at but not really trying at all at (like the protaganist thought she was doing until the art director guy gave her a makeover).

Hey Mike, yeah, I agree that writing should not (or, at least, doesn’t need to) be explicitly about these thing. It also doesn’t have to be obvious that the story is working on this level. I didn’t include that in my question because I want to address the issue more fundamentally.

It’s my preference to read stories that are not directly about these issues.

That’s what art is for, kind of — making something aesthetically do one thing while really doing a lot of other things.

Hey Mike, yeah, I agree that writing should not (or, at least, doesn’t need to) be explicitly about these thing. It also doesn’t have to be obvious that the story is working on this level. I didn’t include that in my question because I want to address the issue more fundamentally.

It’s my preference to read stories that are not directly about these issues.

That’s what art is for, kind of — making something aesthetically do one thing while really doing a lot of other things.

Hey Mike, yeah, I agree that writing should not (or, at least, doesn’t need to) be explicitly about these thing. It also doesn’t have to be obvious that the story is working on this level. I didn’t include that in my question because I want to address the issue more fundamentally.

It’s my preference to read stories that are not directly about these issues.

That’s what art is for, kind of — making something aesthetically do one thing while really doing a lot of other things.

adam,

no we are on the same page. my answer was directed towards general populace than personal experience.

obviously, you are not an accurate model of public/mass thought?

i mean do you really think the millions of people who watched ‘the devil wears prada’ analyzed it, at any capacity, like you have?

or do you think they sat there with dumb filled eyes and giggle guffawed at the dazzle and cutesy?

adam,

no we are on the same page. my answer was directed towards general populace than personal experience.

obviously, you are not an accurate model of public/mass thought?

i mean do you really think the millions of people who watched ‘the devil wears prada’ analyzed it, at any capacity, like you have?

or do you think they sat there with dumb filled eyes and giggle guffawed at the dazzle and cutesy?

adam,

no we are on the same page. my answer was directed towards general populace than personal experience.

obviously, you are not an accurate model of public/mass thought?

i mean do you really think the millions of people who watched ‘the devil wears prada’ analyzed it, at any capacity, like you have?

or do you think they sat there with dumb filled eyes and giggle guffawed at the dazzle and cutesy?

It doesn’t feel right to discuss stories, fiction, poetry, art, music as if the only factor is what it is about. I guess it is said a lot and I don’t like it anymore. ‘I like stories that are ‘about’ this thing or I don’t like science fiction because it is always about this thing.’ What? The fiction, art, etc. that is the most memorable to me is memorable not because of its theme but because of something more mysterious, some sense of mood or atmosphere or personality that I don’t think correlates directly with death or love or aliveness. When things are about these things, then the whole idea of ‘about’ kind of dissolves because everything is about death or love or being alive in some way. I could write a poem about a rock that sits on Neptune for a hundred years and nothing happens and it will be about death or life or love or sex or something because human readers will supply it. Writers shouldn’t try to write about death or love or aliveness, they should write about monkey bowling because if you just write about monkey bowling, your readers will supply the theme, what it means to be a human vs. a monkey, all the inherent sexual metaphors in the game of bowling and how that relates to love etc. even though all you wanted to do was write a story about a monkey bowling league because you thought it would be cute.

It doesn’t feel right to discuss stories, fiction, poetry, art, music as if the only factor is what it is about. I guess it is said a lot and I don’t like it anymore. ‘I like stories that are ‘about’ this thing or I don’t like science fiction because it is always about this thing.’ What? The fiction, art, etc. that is the most memorable to me is memorable not because of its theme but because of something more mysterious, some sense of mood or atmosphere or personality that I don’t think correlates directly with death or love or aliveness. When things are about these things, then the whole idea of ‘about’ kind of dissolves because everything is about death or love or being alive in some way. I could write a poem about a rock that sits on Neptune for a hundred years and nothing happens and it will be about death or life or love or sex or something because human readers will supply it. Writers shouldn’t try to write about death or love or aliveness, they should write about monkey bowling because if you just write about monkey bowling, your readers will supply the theme, what it means to be a human vs. a monkey, all the inherent sexual metaphors in the game of bowling and how that relates to love etc. even though all you wanted to do was write a story about a monkey bowling league because you thought it would be cute.

It doesn’t feel right to discuss stories, fiction, poetry, art, music as if the only factor is what it is about. I guess it is said a lot and I don’t like it anymore. ‘I like stories that are ‘about’ this thing or I don’t like science fiction because it is always about this thing.’ What? The fiction, art, etc. that is the most memorable to me is memorable not because of its theme but because of something more mysterious, some sense of mood or atmosphere or personality that I don’t think correlates directly with death or love or aliveness. When things are about these things, then the whole idea of ‘about’ kind of dissolves because everything is about death or love or being alive in some way. I could write a poem about a rock that sits on Neptune for a hundred years and nothing happens and it will be about death or life or love or sex or something because human readers will supply it. Writers shouldn’t try to write about death or love or aliveness, they should write about monkey bowling because if you just write about monkey bowling, your readers will supply the theme, what it means to be a human vs. a monkey, all the inherent sexual metaphors in the game of bowling and how that relates to love etc. even though all you wanted to do was write a story about a monkey bowling league because you thought it would be cute.

this post made me hot, is that wrong?

the first clause of #1 answers #8. #8 needs to be rephrased by the conditions of the independent clause of #1: temporality and scope of intersubjectivity. the question thus presupposes a specific notion of worth/value (which for the most part i agree with, but is nonetheless unstated).

adam, is there such a thing as the primordial theory? did you just come up with the ideas of this post (distilling it from recurring themes in history/philosophy), or could you point to someone/thing that has formulated these thoughts as well? this stuff is like nose candy (for the brain (if the brain had a nose, this stuff would be its nose candy)), with 100% daily-recommended vitamins and minerals. yay heidegger.

this post made me hot, is that wrong?

the first clause of #1 answers #8. #8 needs to be rephrased by the conditions of the independent clause of #1: temporality and scope of intersubjectivity. the question thus presupposes a specific notion of worth/value (which for the most part i agree with, but is nonetheless unstated).

adam, is there such a thing as the primordial theory? did you just come up with the ideas of this post (distilling it from recurring themes in history/philosophy), or could you point to someone/thing that has formulated these thoughts as well? this stuff is like nose candy (for the brain (if the brain had a nose, this stuff would be its nose candy)), with 100% daily-recommended vitamins and minerals. yay heidegger.

this post made me hot, is that wrong?

the first clause of #1 answers #8. #8 needs to be rephrased by the conditions of the independent clause of #1: temporality and scope of intersubjectivity. the question thus presupposes a specific notion of worth/value (which for the most part i agree with, but is nonetheless unstated).

adam, is there such a thing as the primordial theory? did you just come up with the ideas of this post (distilling it from recurring themes in history/philosophy), or could you point to someone/thing that has formulated these thoughts as well? this stuff is like nose candy (for the brain (if the brain had a nose, this stuff would be its nose candy)), with 100% daily-recommended vitamins and minerals. yay heidegger.

This is good. It helps me form thoughts.

I think the quietly desperate masses probably don’t recognize what their response to mainstream media is based on, but sometimes (generally?) they still have those responses.

Art that incorporates (har har) one of these three modalities probably resonates more, whether or not someone notices.

In TDWP, you’re probably right that people don’t feel inclined to understant what’s at the source of their enjoyment, but at some level it’s still working on them. Especially since that movie is largely about the struggle between intellectuals and fashionistas. I guess we shouldn’t talk about that example anymore though.

I’m trying to think of a wildly popular Hollywood movie that doesn’t something interesting on some level, and I can’t. What is my problem. I have lost all critical faculty. I have become “so open minded my brains have spilled out.” Or whatever my mom fears most.

This is good. It helps me form thoughts.

I think the quietly desperate masses probably don’t recognize what their response to mainstream media is based on, but sometimes (generally?) they still have those responses.

Art that incorporates (har har) one of these three modalities probably resonates more, whether or not someone notices.

In TDWP, you’re probably right that people don’t feel inclined to understant what’s at the source of their enjoyment, but at some level it’s still working on them. Especially since that movie is largely about the struggle between intellectuals and fashionistas. I guess we shouldn’t talk about that example anymore though.

I’m trying to think of a wildly popular Hollywood movie that doesn’t something interesting on some level, and I can’t. What is my problem. I have lost all critical faculty. I have become “so open minded my brains have spilled out.” Or whatever my mom fears most.

This is good. It helps me form thoughts.

I think the quietly desperate masses probably don’t recognize what their response to mainstream media is based on, but sometimes (generally?) they still have those responses.

Art that incorporates (har har) one of these three modalities probably resonates more, whether or not someone notices.

In TDWP, you’re probably right that people don’t feel inclined to understant what’s at the source of their enjoyment, but at some level it’s still working on them. Especially since that movie is largely about the struggle between intellectuals and fashionistas. I guess we shouldn’t talk about that example anymore though.

I’m trying to think of a wildly popular Hollywood movie that doesn’t something interesting on some level, and I can’t. What is my problem. I have lost all critical faculty. I have become “so open minded my brains have spilled out.” Or whatever my mom fears most.

Hi —

I think that the triad you’ve listed is right, and I also agree with the commenters here that there are plenty of subjects that might seem abstruse that can in fact shine light on your ideas of death/love/living…

But I think that there’s also a fourth key that sort of encompasses all three of yours but sort of doesn’t, and I think that this subject matter is day-to-day existence, insofar, at least, as folks go about in a world that drowns them in detail. In other words, a fourth key to interestingness, for me, is: how can people make sense of so much, and how can we make patterns from the patternless? Fiction that seems to do this really well for me includes domestic maximalism — Ian McEwan, Julia Glass, Jonathan Franzen — and also kind of expressionism/high modernism like Under the Volcano, where the details that Lowry draws on are mostly mental/associational but still confront the facts of the world. Of course, this day-to-day pattern finding frequently ends in grand ideas about love/death/living, but sometimes it doesn’t (Glass’s Three Junes strikes me this way, and that book is mega awesome) and still ends up lucid and beautiful and riveting…

This, then, isn’t so much a matter of content-choosing but instead one of sentence- and paragraph-styling, but I guess I kind of subscribe to the modernist idea that form is key, so I always look to style first… And I guess I’d answer #8 by saying that you (one) should take any story as far as possible from the usual as long as you can approach your subject with an eye to lucid-rendering and pattern-finding… This way you get the exotic thrill of model trains and the sense of deeper meaning that I think we agree is central to literary interestingness…

I do think, also, that sometimes people choose to approach exotic/marginal subjects cynically/humorously, and while I think that this is frequently funny it doesn’t pass the interestingness test (or this one, at least) because ultimately the subject of exploration in cynical work is cynicism itself and not the deeper valences of the exotic subject matter…

Maybe I’ve missed the point, but even if I have the question has been super stimulating. Thanks!

Hi —

I think that the triad you’ve listed is right, and I also agree with the commenters here that there are plenty of subjects that might seem abstruse that can in fact shine light on your ideas of death/love/living…

But I think that there’s also a fourth key that sort of encompasses all three of yours but sort of doesn’t, and I think that this subject matter is day-to-day existence, insofar, at least, as folks go about in a world that drowns them in detail. In other words, a fourth key to interestingness, for me, is: how can people make sense of so much, and how can we make patterns from the patternless? Fiction that seems to do this really well for me includes domestic maximalism — Ian McEwan, Julia Glass, Jonathan Franzen — and also kind of expressionism/high modernism like Under the Volcano, where the details that Lowry draws on are mostly mental/associational but still confront the facts of the world. Of course, this day-to-day pattern finding frequently ends in grand ideas about love/death/living, but sometimes it doesn’t (Glass’s Three Junes strikes me this way, and that book is mega awesome) and still ends up lucid and beautiful and riveting…

This, then, isn’t so much a matter of content-choosing but instead one of sentence- and paragraph-styling, but I guess I kind of subscribe to the modernist idea that form is key, so I always look to style first… And I guess I’d answer #8 by saying that you (one) should take any story as far as possible from the usual as long as you can approach your subject with an eye to lucid-rendering and pattern-finding… This way you get the exotic thrill of model trains and the sense of deeper meaning that I think we agree is central to literary interestingness…

I do think, also, that sometimes people choose to approach exotic/marginal subjects cynically/humorously, and while I think that this is frequently funny it doesn’t pass the interestingness test (or this one, at least) because ultimately the subject of exploration in cynical work is cynicism itself and not the deeper valences of the exotic subject matter…

Maybe I’ve missed the point, but even if I have the question has been super stimulating. Thanks!

Hi —

I think that the triad you’ve listed is right, and I also agree with the commenters here that there are plenty of subjects that might seem abstruse that can in fact shine light on your ideas of death/love/living…

But I think that there’s also a fourth key that sort of encompasses all three of yours but sort of doesn’t, and I think that this subject matter is day-to-day existence, insofar, at least, as folks go about in a world that drowns them in detail. In other words, a fourth key to interestingness, for me, is: how can people make sense of so much, and how can we make patterns from the patternless? Fiction that seems to do this really well for me includes domestic maximalism — Ian McEwan, Julia Glass, Jonathan Franzen — and also kind of expressionism/high modernism like Under the Volcano, where the details that Lowry draws on are mostly mental/associational but still confront the facts of the world. Of course, this day-to-day pattern finding frequently ends in grand ideas about love/death/living, but sometimes it doesn’t (Glass’s Three Junes strikes me this way, and that book is mega awesome) and still ends up lucid and beautiful and riveting…

This, then, isn’t so much a matter of content-choosing but instead one of sentence- and paragraph-styling, but I guess I kind of subscribe to the modernist idea that form is key, so I always look to style first… And I guess I’d answer #8 by saying that you (one) should take any story as far as possible from the usual as long as you can approach your subject with an eye to lucid-rendering and pattern-finding… This way you get the exotic thrill of model trains and the sense of deeper meaning that I think we agree is central to literary interestingness…

I do think, also, that sometimes people choose to approach exotic/marginal subjects cynically/humorously, and while I think that this is frequently funny it doesn’t pass the interestingness test (or this one, at least) because ultimately the subject of exploration in cynical work is cynicism itself and not the deeper valences of the exotic subject matter…

Maybe I’ve missed the point, but even if I have the question has been super stimulating. Thanks!

You’re right, but when writing about the rock on Neptune oughtn’t we aspire to the notion of duende that Lorca told us about?

You’re right, but when writing about the rock on Neptune oughtn’t we aspire to the notion of duende that Lorca told us about?

You’re right, but when writing about the rock on Neptune oughtn’t we aspire to the notion of duende that Lorca told us about?

Darby,

I agree with you. What a story or whatever is “about” should be identified by the person taking it in. Writers who start writing with a theme in mind are doing themselves a disservice. In fact, creatively speaking, “theme” is a dirty word, a limitation that stifles expression, as opposed to an obstruction of form or content that creates focus and purpose (like sonnets).

Then again, saying that something is “about” something else isn’t always a reference to theme. I don’t read books looking for a theme. I don’t read books looking for anything in particular. I want to be surprised by language, by what happens, by structure.

Sometimes a cigar is a cigar. Sometimes a rock on Neptune is a rock on Neptune. I’m not sure if this makes any sense.

Darby,

I agree with you. What a story or whatever is “about” should be identified by the person taking it in. Writers who start writing with a theme in mind are doing themselves a disservice. In fact, creatively speaking, “theme” is a dirty word, a limitation that stifles expression, as opposed to an obstruction of form or content that creates focus and purpose (like sonnets).

Then again, saying that something is “about” something else isn’t always a reference to theme. I don’t read books looking for a theme. I don’t read books looking for anything in particular. I want to be surprised by language, by what happens, by structure.

Sometimes a cigar is a cigar. Sometimes a rock on Neptune is a rock on Neptune. I’m not sure if this makes any sense.

Darby,

I agree with you. What a story or whatever is “about” should be identified by the person taking it in. Writers who start writing with a theme in mind are doing themselves a disservice. In fact, creatively speaking, “theme” is a dirty word, a limitation that stifles expression, as opposed to an obstruction of form or content that creates focus and purpose (like sonnets).

Then again, saying that something is “about” something else isn’t always a reference to theme. I don’t read books looking for a theme. I don’t read books looking for anything in particular. I want to be surprised by language, by what happens, by structure.

Sometimes a cigar is a cigar. Sometimes a rock on Neptune is a rock on Neptune. I’m not sure if this makes any sense.

i concur adam.

i think soul is what most of the writers are missing.

i concur adam.

i think soul is what most of the writers are missing.

i concur adam.

i think soul is what most of the writers are missing.

Objective Correlative. Yes. Who coined that again? Eliot or someone like Eliot? I learned this in school and now I can’t remember. Fuck.

Objective Correlative. Yes. Who coined that again? Eliot or someone like Eliot? I learned this in school and now I can’t remember. Fuck.

Objective Correlative. Yes. Who coined that again? Eliot or someone like Eliot? I learned this in school and now I can’t remember. Fuck.

Yeah, yeah, Eliot. I think he meant it as a phenomenon that provokes a response. I’m sure I don’t understand it correctly, but I don’t mind warping it to my purposes.

Yeah, yeah, Eliot. I think he meant it as a phenomenon that provokes a response. I’m sure I don’t understand it correctly, but I don’t mind warping it to my purposes.

Yeah, yeah, Eliot. I think he meant it as a phenomenon that provokes a response. I’m sure I don’t understand it correctly, but I don’t mind warping it to my purposes.

I just got out one of my notebooks from grad school because I am a nerd. This is what I had scribbled down: Objective Correlative: objects and situations that correlate with the emotions of the characters. Akin to a mirror.

Right next to a note that said : The Writer has the ability to make the lives of others last forever, to deal immortality.

Sometimes that’s by writing about death.

I just got out one of my notebooks from grad school because I am a nerd. This is what I had scribbled down: Objective Correlative: objects and situations that correlate with the emotions of the characters. Akin to a mirror.

Right next to a note that said : The Writer has the ability to make the lives of others last forever, to deal immortality.

Sometimes that’s by writing about death.

I just got out one of my notebooks from grad school because I am a nerd. This is what I had scribbled down: Objective Correlative: objects and situations that correlate with the emotions of the characters. Akin to a mirror.

Right next to a note that said : The Writer has the ability to make the lives of others last forever, to deal immortality.

Sometimes that’s by writing about death.

you shouldn’t aspire to duende. you should just have it or not have it.

don’t try. -buk

you shouldn’t aspire to duende. you should just have it or not have it.

don’t try. -buk

you shouldn’t aspire to duende. you should just have it or not have it.

don’t try. -buk

Thanks Keith, I will revisit my languaging of the question. I think you’re making a valid point and I’m glad that you’re directly responding to the question.

As far as I know, no one is bombastic enough to create a system like I’m proposing, but maybe Edmund Husserl’s phenomenology is up your alley. He’s the guy who wanted to “bracket” phenomena in order to get to the ground of being. Husserl, he was Heidegger’s teacher, I think.

Thanks Keith, I will revisit my languaging of the question. I think you’re making a valid point and I’m glad that you’re directly responding to the question.

As far as I know, no one is bombastic enough to create a system like I’m proposing, but maybe Edmund Husserl’s phenomenology is up your alley. He’s the guy who wanted to “bracket” phenomena in order to get to the ground of being. Husserl, he was Heidegger’s teacher, I think.

Thanks Keith, I will revisit my languaging of the question. I think you’re making a valid point and I’m glad that you’re directly responding to the question.

As far as I know, no one is bombastic enough to create a system like I’m proposing, but maybe Edmund Husserl’s phenomenology is up your alley. He’s the guy who wanted to “bracket” phenomena in order to get to the ground of being. Husserl, he was Heidegger’s teacher, I think.

darby,

don’t try, do – buk

he was right about soul.

a suckerfish cannot learn to be a stingray.

give it a name.

whatever.

darby,

don’t try, do – buk

he was right about soul.

a suckerfish cannot learn to be a stingray.

give it a name.

whatever.

darby,

don’t try, do – buk

he was right about soul.

a suckerfish cannot learn to be a stingray.

give it a name.

whatever.

Well, you are wrong, but you are also right.

Well, you are wrong, but you are also right.

Well, you are wrong, but you are also right.

Dammit, my comment is in re darby and not jereme

Dammit, my comment is in re darby and not jereme

Dammit, my comment is in re darby and not jereme

Great questions and answers. Unfortunately, I’m mentally capped today and haven’t much in the way of critical thought! So, yeah! Good job!

Great questions and answers. Unfortunately, I’m mentally capped today and haven’t much in the way of critical thought! So, yeah! Good job!

Great questions and answers. Unfortunately, I’m mentally capped today and haven’t much in the way of critical thought! So, yeah! Good job!

husserl was cool, not so much for the system he created (although he was against systems, which is ironic), but for the method he laid the foundation for: phenomenology. although reading him is fucked. bracketing is cool, yes. i use it sometimes when i am attempting to be aware of the nuances of existence, refraining from projection to thereby increase receptivity of my presence as an extended self in the surrounding space of world disclosing. that’s bullshit, sorry.

i like your system. i like systems. as long as they are recognized as the seran wrap by which we keep our food fresh, the secularity of crumbs. i don’t think husserl really touches on the human condition though, or what you’re talking about above. he’s more in the transcendental realm of abstraction and logic, a mathematics of existence. yeah, he taught heidegger, and heidegger (later as a nazi bastard) screwed him over. heidegger’s philosophy is much closer to having a concern for the human condition (even if not individuals). some of your post echoes heidegger: death (authenticity and being-for) and thrownness. is that why you pic(ed) him?

husserl was cool, not so much for the system he created (although he was against systems, which is ironic), but for the method he laid the foundation for: phenomenology. although reading him is fucked. bracketing is cool, yes. i use it sometimes when i am attempting to be aware of the nuances of existence, refraining from projection to thereby increase receptivity of my presence as an extended self in the surrounding space of world disclosing. that’s bullshit, sorry.

i like your system. i like systems. as long as they are recognized as the seran wrap by which we keep our food fresh, the secularity of crumbs. i don’t think husserl really touches on the human condition though, or what you’re talking about above. he’s more in the transcendental realm of abstraction and logic, a mathematics of existence. yeah, he taught heidegger, and heidegger (later as a nazi bastard) screwed him over. heidegger’s philosophy is much closer to having a concern for the human condition (even if not individuals). some of your post echoes heidegger: death (authenticity and being-for) and thrownness. is that why you pic(ed) him?

husserl was cool, not so much for the system he created (although he was against systems, which is ironic), but for the method he laid the foundation for: phenomenology. although reading him is fucked. bracketing is cool, yes. i use it sometimes when i am attempting to be aware of the nuances of existence, refraining from projection to thereby increase receptivity of my presence as an extended self in the surrounding space of world disclosing. that’s bullshit, sorry.

i like your system. i like systems. as long as they are recognized as the seran wrap by which we keep our food fresh, the secularity of crumbs. i don’t think husserl really touches on the human condition though, or what you’re talking about above. he’s more in the transcendental realm of abstraction and logic, a mathematics of existence. yeah, he taught heidegger, and heidegger (later as a nazi bastard) screwed him over. heidegger’s philosophy is much closer to having a concern for the human condition (even if not individuals). some of your post echoes heidegger: death (authenticity and being-for) and thrownness. is that why you pic(ed) him?

Yeah, totally that’s why I used his picture. In fact, at my blog (publishinggenius.blogspot.com) I specifically identify that third thing as “Heidegger’s thrown-ness”. This post was brought to you by a generous grant from Being and Time’s sections on care.

I like systems too, against my better judgment.

Yeah, totally that’s why I used his picture. In fact, at my blog (publishinggenius.blogspot.com) I specifically identify that third thing as “Heidegger’s thrown-ness”. This post was brought to you by a generous grant from Being and Time’s sections on care.

I like systems too, against my better judgment.

Yeah, totally that’s why I used his picture. In fact, at my blog (publishinggenius.blogspot.com) I specifically identify that third thing as “Heidegger’s thrown-ness”. This post was brought to you by a generous grant from Being and Time’s sections on care.

I like systems too, against my better judgment.

here are some writers i feel have soul.

current:

andy riverbed

sam pink

tony oneill

noah cicero

past:

hunter s. thompson

charles bukowski

frederico garcia lorca

dylan thomas

john fante

this is my opinion. fuck you if you do not like my opinion. fuck you if you like my opinion.

here are some writers i feel have soul.

current:

andy riverbed

sam pink

tony oneill

noah cicero

past:

hunter s. thompson

charles bukowski

frederico garcia lorca

dylan thomas

john fante

this is my opinion. fuck you if you do not like my opinion. fuck you if you like my opinion.

here are some writers i feel have soul.

current:

andy riverbed

sam pink

tony oneill

noah cicero

past:

hunter s. thompson

charles bukowski

frederico garcia lorca

dylan thomas

john fante

this is my opinion. fuck you if you do not like my opinion. fuck you if you like my opinion.

Touche.

Touche.

Touche.

Matt, I read your comment a few times. Good stuff. I think your fourth modality is really just an amalgam of the other three — the drowning details are caused by the condition of being alive, which is what the other three are identifying.

What I’m taken most by here is your notion that your favorite writers are those who elucidate patterns in the muck. I’m reminded of Henry Miller’s line, “You are the sieve through which my anarchy strains, resolves itself into words” (or something like that).

Anyway, I think that’s a good reason to like something and to find it interesting. Like, however the more connections something can make the better.

Matt, I read your comment a few times. Good stuff. I think your fourth modality is really just an amalgam of the other three — the drowning details are caused by the condition of being alive, which is what the other three are identifying.

What I’m taken most by here is your notion that your favorite writers are those who elucidate patterns in the muck. I’m reminded of Henry Miller’s line, “You are the sieve through which my anarchy strains, resolves itself into words” (or something like that).

Anyway, I think that’s a good reason to like something and to find it interesting. Like, however the more connections something can make the better.

Matt, I read your comment a few times. Good stuff. I think your fourth modality is really just an amalgam of the other three — the drowning details are caused by the condition of being alive, which is what the other three are identifying.

What I’m taken most by here is your notion that your favorite writers are those who elucidate patterns in the muck. I’m reminded of Henry Miller’s line, “You are the sieve through which my anarchy strains, resolves itself into words” (or something like that).

Anyway, I think that’s a good reason to like something and to find it interesting. Like, however the more connections something can make the better.

Hi Adam,

Ideas about relevance, communication, significance, meaning, connection, etc. are potentially good starts for dialogue. So thanks for opening up this conversation.

Let me first say that I think the premise with which you began this discussion may be faulty at best, if not outright wrongheaded. The notion that history can be any one monolithic entity can perhaps only lead to one thing, namely, myopia. It might be helpful to define the zone that “indicates…a limited number of topics that are always immediately and profoundly engaging to everyone, all the time,” as you write, as “a” history, rather than simply history. While it would be difficult to prove that there is in fact any history that narrowly measures a work’s significance by how closely it covers a few circumscribed topics, the closest we can come to it is perhaps a paradigm that privileges conventional narrative patterns over disjunctions, disruptions, linearity over multi-linearity, webs, dendritic forms, amorphous shapes. But that paradigm is only one of many. With that as a starting point, I think the dialogue may prove much richer.

At the Publishing Genius blog, you write: “There are only a few things worth writing about: love, death and Heidegger’s ‘thrown-ness.’ Anything that isn’t oriented toward one of these three issues is bad and largely responsible for the high rate of illiteracy in the US.” And here on this blog you flesh out further the “three things worth writing about.” This reminds me of Jonathan Franzen’s argument that was largely, and in wonderful style, debunked by Ben Marcus in his article “Why experimental fiction threatens to destroy publishing, Jonathan Franzen, and life as we know it: A correction.” Considering the estimable roster (Christopher Higg’s new work comes to mind with its first sentence: “Use I this language down complex hallways lined with razor blades you’ve assembled at your press, and fill up the car before bringing it back, will you?”) that you’ve assembled at your press, I wonder if your assertion that work that doesn’t correspond with the “three issues is bad and largely responsible for the high rate of illiteracy in the US,” is largely hyperbolic histrionics. Also, why must art always serve some kind of pedagogic purpose? There are better and frankly actually blameworthy targets for causes of illiteracy than literature that doesn’t engage, in a narrow form, the “human condition,” literature that’s strictly concerned with the semantic vagueness and/ or materiality, indeterminacy, multiplicity, and lexical polyvalence.

Gertrude Stein wrote: “When you realize that…the bible lives not by its stories but by its texts you see how inevitably one wants neither harmony, pictures stories nor portraits. You have to do something else to continue.” She, like Zukofksy, Bunting, Reznikoff, Creely, Davenport, etc. worked within a context where writing is text not story, where normative modes are transgressed, where paratactic syntax is privileged, writing in which “nothing” may actually happen.

All of which leads to my wondering whether there were some writers you had in mind whose work doesn’t fit your description of what is significant literature. Who and what are they? What’s “all this other crap” you’re talking about? It sounds like stuff I might be interested in checking out.

I’ll end by asking: “Conjunction junction what’s your dysfunction?”

Hi Adam,

Ideas about relevance, communication, significance, meaning, connection, etc. are potentially good starts for dialogue. So thanks for opening up this conversation.

Let me first say that I think the premise with which you began this discussion may be faulty at best, if not outright wrongheaded. The notion that history can be any one monolithic entity can perhaps only lead to one thing, namely, myopia. It might be helpful to define the zone that “indicates…a limited number of topics that are always immediately and profoundly engaging to everyone, all the time,” as you write, as “a” history, rather than simply history. While it would be difficult to prove that there is in fact any history that narrowly measures a work’s significance by how closely it covers a few circumscribed topics, the closest we can come to it is perhaps a paradigm that privileges conventional narrative patterns over disjunctions, disruptions, linearity over multi-linearity, webs, dendritic forms, amorphous shapes. But that paradigm is only one of many. With that as a starting point, I think the dialogue may prove much richer.

At the Publishing Genius blog, you write: “There are only a few things worth writing about: love, death and Heidegger’s ‘thrown-ness.’ Anything that isn’t oriented toward one of these three issues is bad and largely responsible for the high rate of illiteracy in the US.” And here on this blog you flesh out further the “three things worth writing about.” This reminds me of Jonathan Franzen’s argument that was largely, and in wonderful style, debunked by Ben Marcus in his article “Why experimental fiction threatens to destroy publishing, Jonathan Franzen, and life as we know it: A correction.” Considering the estimable roster (Christopher Higg’s new work comes to mind with its first sentence: “Use I this language down complex hallways lined with razor blades you’ve assembled at your press, and fill up the car before bringing it back, will you?”) that you’ve assembled at your press, I wonder if your assertion that work that doesn’t correspond with the “three issues is bad and largely responsible for the high rate of illiteracy in the US,” is largely hyperbolic histrionics. Also, why must art always serve some kind of pedagogic purpose? There are better and frankly actually blameworthy targets for causes of illiteracy than literature that doesn’t engage, in a narrow form, the “human condition,” literature that’s strictly concerned with the semantic vagueness and/ or materiality, indeterminacy, multiplicity, and lexical polyvalence.

Gertrude Stein wrote: “When you realize that…the bible lives not by its stories but by its texts you see how inevitably one wants neither harmony, pictures stories nor portraits. You have to do something else to continue.” She, like Zukofksy, Bunting, Reznikoff, Creely, Davenport, etc. worked within a context where writing is text not story, where normative modes are transgressed, where paratactic syntax is privileged, writing in which “nothing” may actually happen.

All of which leads to my wondering whether there were some writers you had in mind whose work doesn’t fit your description of what is significant literature. Who and what are they? What’s “all this other crap” you’re talking about? It sounds like stuff I might be interested in checking out.

I’ll end by asking: “Conjunction junction what’s your dysfunction?”

Hi Adam,

Ideas about relevance, communication, significance, meaning, connection, etc. are potentially good starts for dialogue. So thanks for opening up this conversation.

Let me first say that I think the premise with which you began this discussion may be faulty at best, if not outright wrongheaded. The notion that history can be any one monolithic entity can perhaps only lead to one thing, namely, myopia. It might be helpful to define the zone that “indicates…a limited number of topics that are always immediately and profoundly engaging to everyone, all the time,” as you write, as “a” history, rather than simply history. While it would be difficult to prove that there is in fact any history that narrowly measures a work’s significance by how closely it covers a few circumscribed topics, the closest we can come to it is perhaps a paradigm that privileges conventional narrative patterns over disjunctions, disruptions, linearity over multi-linearity, webs, dendritic forms, amorphous shapes. But that paradigm is only one of many. With that as a starting point, I think the dialogue may prove much richer.

At the Publishing Genius blog, you write: “There are only a few things worth writing about: love, death and Heidegger’s ‘thrown-ness.’ Anything that isn’t oriented toward one of these three issues is bad and largely responsible for the high rate of illiteracy in the US.” And here on this blog you flesh out further the “three things worth writing about.” This reminds me of Jonathan Franzen’s argument that was largely, and in wonderful style, debunked by Ben Marcus in his article “Why experimental fiction threatens to destroy publishing, Jonathan Franzen, and life as we know it: A correction.” Considering the estimable roster (Christopher Higg’s new work comes to mind with its first sentence: “Use I this language down complex hallways lined with razor blades you’ve assembled at your press, and fill up the car before bringing it back, will you?”) that you’ve assembled at your press, I wonder if your assertion that work that doesn’t correspond with the “three issues is bad and largely responsible for the high rate of illiteracy in the US,” is largely hyperbolic histrionics. Also, why must art always serve some kind of pedagogic purpose? There are better and frankly actually blameworthy targets for causes of illiteracy than literature that doesn’t engage, in a narrow form, the “human condition,” literature that’s strictly concerned with the semantic vagueness and/ or materiality, indeterminacy, multiplicity, and lexical polyvalence.

Gertrude Stein wrote: “When you realize that…the bible lives not by its stories but by its texts you see how inevitably one wants neither harmony, pictures stories nor portraits. You have to do something else to continue.” She, like Zukofksy, Bunting, Reznikoff, Creely, Davenport, etc. worked within a context where writing is text not story, where normative modes are transgressed, where paratactic syntax is privileged, writing in which “nothing” may actually happen.

All of which leads to my wondering whether there were some writers you had in mind whose work doesn’t fit your description of what is significant literature. Who and what are they? What’s “all this other crap” you’re talking about? It sounds like stuff I might be interested in checking out.

I’ll end by asking: “Conjunction junction what’s your dysfunction?”

This is a really good post, Adam. You’ve inspired a lot of thoughtful comments.

Unfortunately it’s too late for me to try and be smart; I’ve just resurfaced for air during a mini-break from novella-in-versing (page 230, y’all! Woot!), and now I should get back to it.

Still, I just wanted to chime in and say I like this post. Hopefully I’ll get a chance to come back to it and add something better; hopefully others add more, too.

This is a really good post, Adam. You’ve inspired a lot of thoughtful comments.

Unfortunately it’s too late for me to try and be smart; I’ve just resurfaced for air during a mini-break from novella-in-versing (page 230, y’all! Woot!), and now I should get back to it.

Still, I just wanted to chime in and say I like this post. Hopefully I’ll get a chance to come back to it and add something better; hopefully others add more, too.

This is a really good post, Adam. You’ve inspired a lot of thoughtful comments.

Unfortunately it’s too late for me to try and be smart; I’ve just resurfaced for air during a mini-break from novella-in-versing (page 230, y’all! Woot!), and now I should get back to it.

Still, I just wanted to chime in and say I like this post. Hopefully I’ll get a chance to come back to it and add something better; hopefully others add more, too.

well yeah. 29 people will read a book on racehorses, a million people will read a book on that racehorse that broke the pretty girl’s heart. it still doesn’t mean it’s a good book. devil wears prada is a bad movie. devil wears prada is your hairshirt for publishing chris higgs. that’s the 5th thing people want you to write books about: i was doing the wrong thing until i started doing the right thing and now i’m rich. my heart is worthy just the way it is. even sex and dictatorship is about that–i am loved/i am not loved. well, that’s enough freewill association. Good job!

well yeah. 29 people will read a book on racehorses, a million people will read a book on that racehorse that broke the pretty girl’s heart. it still doesn’t mean it’s a good book. devil wears prada is a bad movie. devil wears prada is your hairshirt for publishing chris higgs. that’s the 5th thing people want you to write books about: i was doing the wrong thing until i started doing the right thing and now i’m rich. my heart is worthy just the way it is. even sex and dictatorship is about that–i am loved/i am not loved. well, that’s enough freewill association. Good job!

well yeah. 29 people will read a book on racehorses, a million people will read a book on that racehorse that broke the pretty girl’s heart. it still doesn’t mean it’s a good book. devil wears prada is a bad movie. devil wears prada is your hairshirt for publishing chris higgs. that’s the 5th thing people want you to write books about: i was doing the wrong thing until i started doing the right thing and now i’m rich. my heart is worthy just the way it is. even sex and dictatorship is about that–i am loved/i am not loved. well, that’s enough freewill association. Good job!

dude heidegger. yes. throwness. anguish. husserl was heidegger’s teacher. “cartesian meditations” is the bomb.

dude heidegger. yes. throwness. anguish. husserl was heidegger’s teacher. “cartesian meditations” is the bomb.

dude heidegger. yes. throwness. anguish. husserl was heidegger’s teacher. “cartesian meditations” is the bomb.

Ah the cogito.

Ah the cogito.

Ah the cogito.

Hi John, you say

“While it would be difficult to prove that there is in fact any history that narrowly measures a work’s significance by how closely it covers a few circumscribed topics, the closest we can come to it is perhaps a paradigm that privileges conventional narrative patterns over [unconventional ones]. But that paradigm is only one of many. With that as a starting point, I think the dialogue may prove much richer.”

but I think it’s ludicrous to confine a topic about theme to considerations of style. My thought experiment has nothing to do with the tone of voice or syntactic structure in which something is written. I’m only interested in subject matter here. Undrop your jaws, y’all. Of course, I’m a fan of the “form is content” perspective that I think all savvy writers are working from this last century, so I acknowledge that The Age of Wire and String adequately addresses my proposed modalities while tricking out my Wernicke area, but I am certainly not arguing that, by being aware of death, love, or thrownness while conceptualizing a story a writer is confined to unconventional, avant garde forms.

So, for whatever reason, I think you’ve misunderstood me. I think you projected onto me! WTF dude! Don’t project those lame ideas on me! Why does everyone think I am so wonked out for meaning? For pedagogy in art? That ain’t me, and I’m glad to see it confused you a little to think that’s what I could be saying, John,

given the PGP roster. I hate meaning and Jesus just as much as the next guy.

I’m not often accused of siding with Franzen, though in these comments we’ve had one long, thoughtful comment from a fan of his, and now a backhanded putdown of him.

And also a couple people asked what is “all this other crap” I’m referring to. Don’t think I’m not catching your snarky subtext there — if I don’t like it then it must be something you’d like, because if I don’t like it then it’s going to be doing interesting things with parataxis probably. Maybe I’ll compile a list at some point but really I’m just thinking of everything I start reading on the internet and then stop reading.

OK. Thanks John, you have a good headful of thoughts. They just don’t apply to what I’m positing.

Hi John, you say

“While it would be difficult to prove that there is in fact any history that narrowly measures a work’s significance by how closely it covers a few circumscribed topics, the closest we can come to it is perhaps a paradigm that privileges conventional narrative patterns over [unconventional ones]. But that paradigm is only one of many. With that as a starting point, I think the dialogue may prove much richer.”

but I think it’s ludicrous to confine a topic about theme to considerations of style. My thought experiment has nothing to do with the tone of voice or syntactic structure in which something is written. I’m only interested in subject matter here. Undrop your jaws, y’all. Of course, I’m a fan of the “form is content” perspective that I think all savvy writers are working from this last century, so I acknowledge that The Age of Wire and String adequately addresses my proposed modalities while tricking out my Wernicke area, but I am certainly not arguing that, by being aware of death, love, or thrownness while conceptualizing a story a writer is confined to unconventional, avant garde forms.

So, for whatever reason, I think you’ve misunderstood me. I think you projected onto me! WTF dude! Don’t project those lame ideas on me! Why does everyone think I am so wonked out for meaning? For pedagogy in art? That ain’t me, and I’m glad to see it confused you a little to think that’s what I could be saying, John,

given the PGP roster. I hate meaning and Jesus just as much as the next guy.

I’m not often accused of siding with Franzen, though in these comments we’ve had one long, thoughtful comment from a fan of his, and now a backhanded putdown of him.

And also a couple people asked what is “all this other crap” I’m referring to. Don’t think I’m not catching your snarky subtext there — if I don’t like it then it must be something you’d like, because if I don’t like it then it’s going to be doing interesting things with parataxis probably. Maybe I’ll compile a list at some point but really I’m just thinking of everything I start reading on the internet and then stop reading.

OK. Thanks John, you have a good headful of thoughts. They just don’t apply to what I’m positing.

Hi John, you say

“While it would be difficult to prove that there is in fact any history that narrowly measures a work’s significance by how closely it covers a few circumscribed topics, the closest we can come to it is perhaps a paradigm that privileges conventional narrative patterns over [unconventional ones]. But that paradigm is only one of many. With that as a starting point, I think the dialogue may prove much richer.”

but I think it’s ludicrous to confine a topic about theme to considerations of style. My thought experiment has nothing to do with the tone of voice or syntactic structure in which something is written. I’m only interested in subject matter here. Undrop your jaws, y’all. Of course, I’m a fan of the “form is content” perspective that I think all savvy writers are working from this last century, so I acknowledge that The Age of Wire and String adequately addresses my proposed modalities while tricking out my Wernicke area, but I am certainly not arguing that, by being aware of death, love, or thrownness while conceptualizing a story a writer is confined to unconventional, avant garde forms.

So, for whatever reason, I think you’ve misunderstood me. I think you projected onto me! WTF dude! Don’t project those lame ideas on me! Why does everyone think I am so wonked out for meaning? For pedagogy in art? That ain’t me, and I’m glad to see it confused you a little to think that’s what I could be saying, John,

given the PGP roster. I hate meaning and Jesus just as much as the next guy.

I’m not often accused of siding with Franzen, though in these comments we’ve had one long, thoughtful comment from a fan of his, and now a backhanded putdown of him.

And also a couple people asked what is “all this other crap” I’m referring to. Don’t think I’m not catching your snarky subtext there — if I don’t like it then it must be something you’d like, because if I don’t like it then it’s going to be doing interesting things with parataxis probably. Maybe I’ll compile a list at some point but really I’m just thinking of everything I start reading on the internet and then stop reading.

OK. Thanks John, you have a good headful of thoughts. They just don’t apply to what I’m positing.

I don’t understand why I need to wear a hairshirt for publishing Chris Higgs? I’m proud of that book.

I don’t understand why I need to wear a hairshirt for publishing Chris Higgs? I’m proud of that book.

I don’t understand why I need to wear a hairshirt for publishing Chris Higgs? I’m proud of that book.

Hi Adam,

I was looking forward to a refutation but instead you’ve more or less hammered in what’s already screwed to begin with. I’m not sure if telling us what you’re not talking about is helpful. Concrete examples would only serve to clarify what it is you’re actually positing. Not having examples makes it enormously difficult to address what is you’re saying.

The first point I made was that what you’re defining as “history” should only be understood as “Adam’s personal taste.” History is no monolithic thing. It isn’t one giant umbrella under which everything and everyone is covered. There are countless umbrellas. Some bigger and stronger, others smaller and weaker. Who’s to say or determine which umbrella is the most significant? What’s the criteria anyway, and who’s coming up with it and why? I think history’s a concept (my own umbrella), and like any concept it is imagined. Attempts to turn “an” umbrella into “the” umbrella, turns it not into “the” umbrella, but into a bludgeon, a steamroller.

So, if we revise your first point to read:

“While any subject can be interesting to anyone whose interests don’t reflect mine at any given time, my personal taste indicates that there are a limited number of topics that are always immediately and profoundly engaging to me, all the time.”

And the seventh to read:

“So my question is, what is all this other crap that people are writing, that is, everything I start reading on the internet and then stop reading? For instance, [Insert list of “crap” practitioners here].”

And the eighth to read:

“In other words, how far from these issues can a writer take a story and still have a story that my personal taste considers important?”

Then we may actually get closer to what it is you mean. As I said before, telling us what you don’t mean hasn’t brought us anywhere closer to what you do.

As for the “human condition”: anything imagined, constructed, regarded by a person addresses in some way the human condition (it probably makes sense to write “a” human condition). So then, is everything significant? But is this the only measure of significance? I would argue that, no, it is a preference, an umbrella. And, considering that it’s just one umbrella among many, there’s certainly nothing wrong with that.

You write:

“I think it’s ludicrous to confine a topic about theme to considerations of style. My thought experiment has nothing to do with the tone of voice or syntactic structure in which something is written. I’m only interested in subject matter here.”

I’d like for you to demonstrate how style, tone of voice, syntactic structure may be divested of and from “subject matter” anyway. What you’re talking about is your narrow parameter of worthy subjects. You haven’t demonstrated at all why work that’s divested from the narrow confines of subject matter as you defined, i.e. love, death, idea of life, etc. should be considered insignificant.

You write:

“Of course, I’m a fan of the “form is content” perspective that I think all savvy writers are working from this last century, so I acknowledge that The Age of Wire and String adequately addresses my proposed modalities while tricking out my Wernicke area, but I am certainly not arguing that, by being aware of death, love, or thrownness while conceptualizing a story a writer is confined to unconventional, avant garde forms.”

Glad to hear it. As you haven’t shown us the writing you have such strong feelings against, however, it’s hard, if not impossible, to ascertain what it is you’re referring to.

You write:

“So, for whatever reason, I think you’ve misunderstood me…Why does everyone think I am so wonked out for meaning? For pedagogy in art? That ain’t me…”

You’re being slippery here. I would say that if a lot of people think you’re “wonked out for meaning,” then it might be good to take stock. Or not. As for art and pedagogy, what did you mean on your blog–which needs to be considered in tandem with your entry here–when you wrote?

You write:

“There are only a few things worth writing about: love, death and Heidegger’s thrown-ness. Anything that isn’t oriented toward one of these three issues is bad and largely responsible for the high rate of illiteracy in the US.”

Here you’ve linked whatever writing you don’t consider significant as being “largely responsible for the high rate of illiteracy in the US.” How did I misread this? Illiteracy is created by deliberate, disproportionate distribution of resources, i.e. schools, teachers, books, access to literate environments, etc. In other words, if you want to decrease illiteracy, and crime for that matter, then decrease poverty.

You know, if I handed one of the books from Publishing Genius (an accomplished roster indeed) to an illiterate, it would be the same as handing almost any printed matter to him or her. From a daily tabloid to Finnegan’s Wake, no matter how impenetrable, vacant, devoid of “meaning” or “subject matter,” or the opposite, for that matter, a piece of writing is, reading, let alone understanding, that piece will only be relevant to an illiterate when personal value is accorded to reading, and that won’t happen until poverty is eradicated, etc. Here I think you either have to cop having conflated “bad” (at least in your determination) literature with illiteracy’s the primary cause. Or better yet, retract.

Actually my interest in “this other crap” comes from really

wanting to know what you’re talking about, with the possibility, yes, that there may be stuff that I like, but also with the likelihood that there’ll be some “crap” that I’ll need to open up my umbrella as a shield against.

As for having a “headful of thoughts,” thanks, but I often feel like I’m like the guy working on “Maggie’s Farm,” having a “head full of ideas that are driving me insane.”

Check out the Franzen article, if you haven’t already, and get back to me on where you think you fit in, or not.

Rock on,

John

Hi Adam,

I was looking forward to a refutation but instead you’ve more or less hammered in what’s already screwed to begin with. I’m not sure if telling us what you’re not talking about is helpful. Concrete examples would only serve to clarify what it is you’re actually positing. Not having examples makes it enormously difficult to address what is you’re saying.

The first point I made was that what you’re defining as “history” should only be understood as “Adam’s personal taste.” History is no monolithic thing. It isn’t one giant umbrella under which everything and everyone is covered. There are countless umbrellas. Some bigger and stronger, others smaller and weaker. Who’s to say or determine which umbrella is the most significant? What’s the criteria anyway, and who’s coming up with it and why? I think history’s a concept (my own umbrella), and like any concept it is imagined. Attempts to turn “an” umbrella into “the” umbrella, turns it not into “the” umbrella, but into a bludgeon, a steamroller.

So, if we revise your first point to read:

“While any subject can be interesting to anyone whose interests don’t reflect mine at any given time, my personal taste indicates that there are a limited number of topics that are always immediately and profoundly engaging to me, all the time.”

And the seventh to read:

“So my question is, what is all this other crap that people are writing, that is, everything I start reading on the internet and then stop reading? For instance, [Insert list of “crap” practitioners here].”

And the eighth to read:

“In other words, how far from these issues can a writer take a story and still have a story that my personal taste considers important?”

Then we may actually get closer to what it is you mean. As I said before, telling us what you don’t mean hasn’t brought us anywhere closer to what you do.

As for the “human condition”: anything imagined, constructed, regarded by a person addresses in some way the human condition (it probably makes sense to write “a” human condition). So then, is everything significant? But is this the only measure of significance? I would argue that, no, it is a preference, an umbrella. And, considering that it’s just one umbrella among many, there’s certainly nothing wrong with that.

You write:

“I think it’s ludicrous to confine a topic about theme to considerations of style. My thought experiment has nothing to do with the tone of voice or syntactic structure in which something is written. I’m only interested in subject matter here.”

I’d like for you to demonstrate how style, tone of voice, syntactic structure may be divested of and from “subject matter” anyway. What you’re talking about is your narrow parameter of worthy subjects. You haven’t demonstrated at all why work that’s divested from the narrow confines of subject matter as you defined, i.e. love, death, idea of life, etc. should be considered insignificant.

You write:

“Of course, I’m a fan of the “form is content” perspective that I think all savvy writers are working from this last century, so I acknowledge that The Age of Wire and String adequately addresses my proposed modalities while tricking out my Wernicke area, but I am certainly not arguing that, by being aware of death, love, or thrownness while conceptualizing a story a writer is confined to unconventional, avant garde forms.”

Glad to hear it. As you haven’t shown us the writing you have such strong feelings against, however, it’s hard, if not impossible, to ascertain what it is you’re referring to.

You write:

“So, for whatever reason, I think you’ve misunderstood me…Why does everyone think I am so wonked out for meaning? For pedagogy in art? That ain’t me…”

You’re being slippery here. I would say that if a lot of people think you’re “wonked out for meaning,” then it might be good to take stock. Or not. As for art and pedagogy, what did you mean on your blog–which needs to be considered in tandem with your entry here–when you wrote?

You write:

“There are only a few things worth writing about: love, death and Heidegger’s thrown-ness. Anything that isn’t oriented toward one of these three issues is bad and largely responsible for the high rate of illiteracy in the US.”

Here you’ve linked whatever writing you don’t consider significant as being “largely responsible for the high rate of illiteracy in the US.” How did I misread this? Illiteracy is created by deliberate, disproportionate distribution of resources, i.e. schools, teachers, books, access to literate environments, etc. In other words, if you want to decrease illiteracy, and crime for that matter, then decrease poverty.

You know, if I handed one of the books from Publishing Genius (an accomplished roster indeed) to an illiterate, it would be the same as handing almost any printed matter to him or her. From a daily tabloid to Finnegan’s Wake, no matter how impenetrable, vacant, devoid of “meaning” or “subject matter,” or the opposite, for that matter, a piece of writing is, reading, let alone understanding, that piece will only be relevant to an illiterate when personal value is accorded to reading, and that won’t happen until poverty is eradicated, etc. Here I think you either have to cop having conflated “bad” (at least in your determination) literature with illiteracy’s the primary cause. Or better yet, retract.

Actually my interest in “this other crap” comes from really

wanting to know what you’re talking about, with the possibility, yes, that there may be stuff that I like, but also with the likelihood that there’ll be some “crap” that I’ll need to open up my umbrella as a shield against.

As for having a “headful of thoughts,” thanks, but I often feel like I’m like the guy working on “Maggie’s Farm,” having a “head full of ideas that are driving me insane.”

Check out the Franzen article, if you haven’t already, and get back to me on where you think you fit in, or not.

Rock on,

John

Hi Adam,

I was looking forward to a refutation but instead you’ve more or less hammered in what’s already screwed to begin with. I’m not sure if telling us what you’re not talking about is helpful. Concrete examples would only serve to clarify what it is you’re actually positing. Not having examples makes it enormously difficult to address what is you’re saying.

The first point I made was that what you’re defining as “history” should only be understood as “Adam’s personal taste.” History is no monolithic thing. It isn’t one giant umbrella under which everything and everyone is covered. There are countless umbrellas. Some bigger and stronger, others smaller and weaker. Who’s to say or determine which umbrella is the most significant? What’s the criteria anyway, and who’s coming up with it and why? I think history’s a concept (my own umbrella), and like any concept it is imagined. Attempts to turn “an” umbrella into “the” umbrella, turns it not into “the” umbrella, but into a bludgeon, a steamroller.

So, if we revise your first point to read:

“While any subject can be interesting to anyone whose interests don’t reflect mine at any given time, my personal taste indicates that there are a limited number of topics that are always immediately and profoundly engaging to me, all the time.”

And the seventh to read:

“So my question is, what is all this other crap that people are writing, that is, everything I start reading on the internet and then stop reading? For instance, [Insert list of “crap” practitioners here].”

And the eighth to read:

“In other words, how far from these issues can a writer take a story and still have a story that my personal taste considers important?”

Then we may actually get closer to what it is you mean. As I said before, telling us what you don’t mean hasn’t brought us anywhere closer to what you do.