Random

Reconsidering Existential Texts in a Mario Broian Context

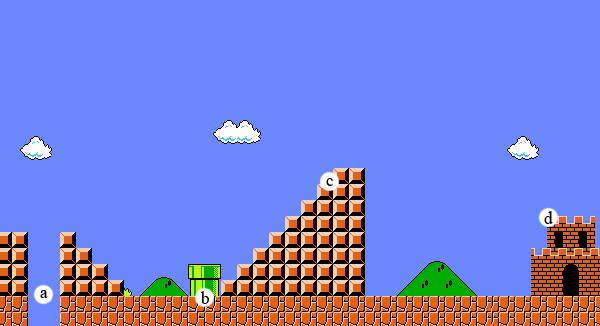

The Fall of Man’s vector is of course down, a direction consistent with our tiered notion of heaven and hell, the latter’s visceral intuition made more compelling by natural physical laws, that is, the acceleration of gravity precluded by the surface on which its falling object lands. Though we never hear Mario land some 60 ft. below, breaking all his bones and liquifying his internal organs, his final breaths squeaking through paralysis. He simply dies — or rather, his death is commemorated by his very reincarnation — before he actually dies, before we hear his cries. One could offer, however, that the pit never ends, towards the core of the earth it falls until upward again and out the other side. Camus’ last novel (a) The Fall, claimed by Sartre to be “perhaps the most beautiful and the least understood” of his books, amounts to a long-winded dramatic confession that one Clamence tells to a stranger, presumably at a bar or cafe. Its entire conceit is verbally excessive unfiltered honesty, a kind of half-assed solution to both the problem of the novel (who and why is the voice) and the ontological matter its title invokes. Controlled falling, or “capable descent,” shares the former’s direction but not its acceleration or volition; we see Mario voluntarily going underground — for Faustian coins perhaps, before the days of #occupyworld1 — like an impulsive self-punishing Dostoyevsky in (b) Notes From the Underground, whose narrator is given, by the swift auspices of its first-person diary conceit, full aesthetic license to tirelessly ramble on about things “from his head.” Hate me for saying this, but I found it rather annoying. And don’t be upset if tumblr killed blogging, for blogging killed livejournal, which killed the diary — the pad-locked memoir once of and for the sole author (and concerned parents during grave transgressions of privacy) now shining brightly inside the laptop rectangular-lit rooms of similar demographic, each one reading, finding, themselves in another stranger with their beautiful i’s. Where Fyodor failed, young girls with achy emotions picked up, smoothly, the heart “special character” inked a dense black ♥♥♥♥♥♥♥♥ over and over again as a typed password only they knew. In a kind of existential geometry, an implicit pictorial math in our minds, we envision a wall as being 90° upright, and a hill, conceptually, as 45°; thus (c)‘s penultimate little hops until Mario’s critical leap seems more akin too Camus’ The Myth of Sissyphus than Jean-Paul Sartre’s The Wall, though both texts implicate, perhaps masochistically celebrate, the eternal preclusion of spiritual arrival. From 1-1 to 2-1 etc., his transcendence to each new world merely illusory, Mario finds himself climbing the same wall at the end, around the same time in vaguely altered template worlds, with the same stubborn conviction that this time will be the end, a final leap into a black screen noting the copy-righted year the game was made. Let us ignore the princess, for the deflation of pursuing, attaining, and remembering a booty call (to see this allegory anthropologically) is perhaps more depressing than Nietzsche’s grounded down yellow molars, who is only mentioned here because he was the one with the best hair. One wonders if inside Kafka’s (d) The Castle waited a pretty girl, hands politely clasped by her groin, as if self-censored by the very pixels with which she is made. (Das Schloß, its original German title, contains a beta, Kafka the ultimate beta male, second to alpha but so much beta.) M. enters the castle into a labyrinthian world, tasked with memorizing absurd invisible patterns, the bureaucracy of human itinerary, stumbling across the same scene in a loop of déjà vu. The player, the boy at home marking his greasy controllers more so by his latest Doritos binge, knows the joke though: Mario needs to go in an exact sequence in order to “unlock” the loop and move towards his eventual demise, met by either his harrowing death; or existentially, when the boy wins the game and turns the Nintendo off. The neurological explanation of déjà vu reduces those perceived moments to a tired brain simply sensing “real time” a nanosecond slower than its memory of it, thus reasoning that everything has oddly happened already. The optimistic, or mystic, will offer reincarnation as a reason — the bit about atoms never being destroyed but merely changing form from John to rat to Joan to bat. The sage oft sings things, clouding up the room. You may have forgotten about Mario, currently signing waivers and disclaimers saying he’s aware that the fiery balls may be fatal, that the dragon is Man himself, or that the princess might be a man. Godless, angry, the pen is pushed. Welcome to words. Boy wins Super Mario Bros and goes downstairs to tell his Mom about it. Mom says go to college. Boy goes to college and learns to cover pieces of copier paper with black words. Boy is allowed into the dorm but doesn’t feel like he belongs there, but “taking certain auxiliary circumstances into account,” is permitted humiliating access. Boy sees girl behind mouth breather. Boy dies but is somehow alive again.

[Author acknowledges Matt Bell and Brian Oliu for their earlier takes.]

good read, jimmy

more fun than ive had in a while.

liked the waivers and atoms bit towards the end. The Fall was Camus’ last novel? crazy, it is weird and rambly (though I liked it) like Notes for the underground. Maybe we can blame Notes from the underground for some of the 20th century more run-on 1st person narratives; thought I like that also; yet it seems that a minmalist could write the story in 20 pages.

I actually won Super Mario Bros. through the Wii, like a couple months ago; I told my girlfriend, not my mom.

http://tinyurl.com/8a4vnr5

i wrote some Mario World haiku.