Random

Some Notes on the First Two Poems in Saint Monica, by Mary Biddinger

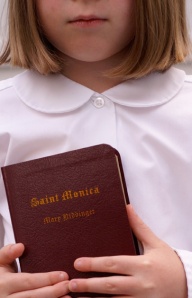

Saint Monica begins with an entry from the online Patron Saints Index. It goes like so:

Memorial: 27 August

Mother of Saint Augustine of Hippo, whose writers about her are the primary source of our information. A Christian from birth, she was given in marriage to a bad-tempered adulterous pagan named Patricius. She prayed constantly for the conversion of her husband (who converted on his death bed), and of her son (who converted after a wild life). Spiritual student of St. Ambrose of Milan. Reformed alcoholic.

Born 322 at Tagaste (South Ahrus), Algeria.

Died 387 at Ostia, Italy

Patronage: abuse victims, alcoholics, alcoholism, difficult marriages, disappointing children, homemakers, housewives, married women, mothers, victims of adultery, victims of unfaithfulness, victims of verbal abuse, widows, wives.

Then we get a dedication: “For all the girls with names that begin with M.” The reader notices right away that the author’s first name begins with M.

Already, by the dedication, before the first poem begins, the reader is attuned to a strange quality that attaches to the cult of saints, which is that their personhood is inextricably mingled with the personhood of the latter-day people who revere them. Saint Monica, mother of St. Augustine, was born in Africa in the fourth century, and died in Italy sixty-some years later. What has that to do with American girls whose named begin with M., in the twenty- and twenty-first century? What is the relationship between the Saint Monica of help and reverence and the Saint Monica who gave birth to a son, took up and then gave up devotion to alcohol, and studied with St. Ambrose, more than 1700 years ago?

Time and tradition have warped a flesh-and-blood person into an abstraction useful to contemporary people for whom knowledge of Saint Monica comes indirectly, through the words of others. So there isn’t a single Saint Monica of tradition. Instead, there are as many Saint Monicas as there are latter-day imaginers of Saint Monica. The person Monica was becomes conflated in the mind of the person who imagines a version of Saint Monica with the things inside the imaginer that give rise to the imaginer’s version of Saint Monica, so Saint Monica becomes out of joint, time-wise. She can’t be the fourth century Monica anymore, because that Monica is dead and mostly lost to memory. All that remains of her is some words written by other people. What replaces that Monica is a new idea and cult of Monica, and a little army of abstract Monicas that exist in the imagination of those for whom this or that idea of Saint Monica is useful.

It is not surprising, then that the first poem in Mary Biddinger’s Saint Monica introduces us to a Saint Monica who is clearly a contemporary person. That poem, “Saint Monica of the Gauze,” begins like this:

The room is red with iodine. Her ears stop

and her thighs slacken against

the bed. . . .

Soon we get news of “the goldfinch / bathing in a pile of spilled parmesan / in the convenience store parking lot,” static wracking the telephone line, and “a dry tornado / on the helipad after the freeway crash.” She’s been rolled in on a gurney. We’re in a hospital, clearly, with linoleum floors that have seen “years of other feet / and beds rolling in and out.” But there’s a heightening. It’s not the gauze that’s red with iodine. It’s the room.

The poem holds forth the trouble that precipitated Saint Monica’s arrival in the hospital, and the trouble that requires her to lay in the iodine-red room, but there is also another trouble outside the room. Amid reports of the plants Monica isn’t tending on account of being here, the “they” who hauled her from the gurney ask about “the clematis / your husband promised to burn if it / came back?”

It’s not difficult to read that line the first time and consider that Saint Monica’s husband might be inclined to violence of the sort that extends beyond plants to people. And clematis is a freighted choice of plant to burn. According to tradition, wild clematis is the plant that gave shelter to Mary and Jesus during their flight to Egypt. What a thing to burn!

The poem ends like this:

. . . They say that she will get out.

There will be time and muscle

enough for hanging wet towels on a line.

The reader notices how we’ve gone an entire poem without hearing from Monica herself. Everything is coming from “They,” and They is always a problematic construct, in literature and in life. Do They get it right?, and if They do get it right, for whom do they get it right? For They, or for Monica?

The reader also notices how our introduction to this Saint Monica is as “Saint Monica of the Gauze.” Gauze is a thing that is offered when there is a wound, when there is bleeding. Gauze is offered as an aid to healing, but it is also a thing that can harbor infection if it is not frequently changed. Gauze requires constant intervention, constant tending, constant changing. Gauze is not a permanent condition, but instead it is a waystation, either to healing or to decline.

If healing is in the cards, what awaits Saint Monica when she gets out, if They are right to say she will? What does it mean that the available time and muscle will allow for “hanging wet towels on a line”? There is a heaviness in the image. The reader worries for her.

In the second poem, Monica is transformed into “Saint Monica of the Ice.” Immediately, we get the return of They:

No, they would never find her under the ice

like a lost scarf snowed away for months

and replaced. . . .

This Monica “didn’t even know the cold, / had to lie when friends asked about her / bare legs under a kilt, the muslin slips / she slept in, . . .” Unlike “the rest,” who huddle, “hot bricks at their toes” on cold January nights, Monica sleeps beneath cracked windows. When she falls into the icy river, no one pulls her out. She pulls herself out, before the attempted and problematic intervention of a teacher and a rope.

It is a testament to Biddinger’s skill as a manipulator of words and images that it is difficult to write summary of these poems, and not because they resist the reader’s attempt to understand them or to fall into them–Clarity is one of their virtues–but, rather, because once she begins to set everything into motion, the literal surfaces spin a web of attachment that causes the reader to understand many things at once, which means an attempt to summarize what is happening in important lines of a poem like “Saint Monica of the Thaw” requires a lot more space than the lines themselves require.

For example, here is the poem’s concluding lines, which follow Monica’s fall into the icy river, her climb out, and the somersault of a teacher and a rope down “the crusted ledge”:

Monica did not even peel off her coat

before untangling Miss Nells, brushing

the snow from her pin curls, flipping her

skirt back over her knees. How did she

keep quiet about the dingy pantalets, red

garter hidden under all that wool, the way

the rope knotted itself around them both.

It’s not just the exterior action that the poem is being clear about. The poem is spinning a web of inferences. The teacher comes to the rescue of the poor girl, but then it is the poor girl who actually does the rescuing. The rescuing doesn’t just come in the form of physical rescue. There is also a rush to save dignity, by “flipping her skirt back over her knees.” But this is also a concealing move. It shows something about what’s important to the community both characters inhabit. It’s telling that the first move isn’t to comfort or warm or untangle, but rather to conceal. And the thing that is concealed is that which the skirt covers. And what it covers is not only “the dingy pantalets” — an image that conveys dirtiness, poverty, ruin, and smallness all at once — but also the “red garter hidden under all that wool.” And here we’re into the intrigue of the suppression of female sexuality.

It’s a strange thing about skirts. They conceal, but they also tease, because they are open, and they are mobile. It is possible, sometimes, when they move, to catch a glimpse of what is beneath them. And what is beneath them? It could be dingy pantalets, and it could be a red garter, and it could be both. Or there could be no fabric at all. The skirt, in a place and time like Monica inhabits, is a necessary thing for a virtuous woman to wear, to show and own her apartness, at the level of the uniform, from the pants-wearing men. It keeps their eyes away from the shape and the form of the legs and the place where the legs meet. But it also invites attention to the places it covers. In hiding, it also invites speculation about what is hidden. Somehow, it is natural for the speculators to speculate, but it is wrong for the hiders to unhide, even if the unhiding is accidental. Even if the unhiding is the thing the speculators desire, and even if the speculators enjoy the unhiding, the unhider is shamed by the unhiding, and the speculator is not shamed.

And what is happening between this teacher, Miss Nells, and Saint Monica, when one or the other of them is keeping quiet not only about the dingy pantalets and the red garter, but also about “the way / the rope knotted itself around them both?” And what does it mean that they find this condition after a botched rescue, both of them wet and cold? And what does it mean that the putative instrument of rescue — the rope — becomes a thing that binds? Once the figurative is introduced, it is nearly impossible to succinctly summarize what is happening in the poem, because so many things are happening. The moment in the poem offers what a moment of life might offer an observer if it the moment observed not simply as a snapshot of surface events but instead as an experience that attaches to all the previous experiences, and all the knowledge we have of the world and the people in it and the way they think and the way the patterns of thinking and the patterns of understanding they have achieved in community bear upon the way They understand the moment, and the ways in which They’s understanding of a moment is a central agent that brings the consequences the individual experiences because of what happened in that moment. Saint Monica’s identity isn’t something Monica gets to construct on her own. The workings of They and the tyranny of they in some ways have more to do with the persona of Saint Monica than Monica herself does.

This is something the book is constantly interrogating. What does it mean to be a person? What does it mean to be an individual? What does it mean to be a saint? Who gets to determine who and what we are? What matters more, what is more lasting: The individual, or the persona? For whom are these things useful, and how and why? What does it mean, to identify an individual with a persona? What does it mean for the individual? What does it mean for the observer? What does it mean for the community from which all of this rises?

Hey Kyle Minor, welcome back.

Shit, this is great Kyle. Where’ve you been?

[…] a lot more space than the lines themselves require.” Read the entire thoughtful review here, and pick up your copy of Saint Monica here. Like this:LikeBe the first to like this post. This […]

ken baumann nudes

Is Saint Augustine’s exegesis of the 2nd and 3rd chapters of Genesis correct? Do a search: First Scandal.

[…] A few weeks back, the inimitable Toledo-based writer Kyle Minor offered a wonderfully insightful writeup about the first two poems in Saint Monica at HTML […]