Random

The Hero’s Body

This post is an essay about comic books and sex. These are things I am thinking about because of a book I am writing.

In May of 1962, the brilliant scientist Bruce Banner rushed into the site of an experimental gamma bomb detonation in order to save a teenager, young Rick Jones, from the blast. Banner stood at the blast’s center. His body absorbed a massive dose of gamma radiation. Banner soon found that when he lost control of his temper, he would become the Hulk, a super-strong, bulky monster with green skin and the collective smarts of a box of rocks. The Hulk was originally more of a monster than a hero, back when monster books still sold; Stan Lee created him by combining him with Frankenstein’s creature and the Hyde of Jekyll and Hyde. He also compared him to the golem. The Hulk looks like this:

In January 1981, Jennifer Susan Walters was shot by mobsters. To save her life, her cousin Bruce Banner offered his blood for a transfusion. The gamma radiation turned her into the She-Hulk.

Wikipedia explains the pragmatic reason for the creation of She-Hulk:

She-Hulk was created by Stan Lee, who wrote only the first issue, and was the last character he created for Marvel before his return to comics with Ravage 2099 in 1992. The reason for the character’s creation had to do with the success of the Incredible Hulk TV series (1977–82). Afraid that the show’s executives would suddenly introduce a female Hulk, resembling the popularBionic Woman, Marvel decided to publish their own version of such a character to make sure that if a similar one showed up in the TV series, they would own the rights.

She-Hulk looks like this:

You can’t really call her a “Hulk.” The Hulk is a character named for his shape. It’s not an especially appealing shape, sexually speaking. There are maybe two women alive who see the Hulk and think, “I’d like to kiss that hulk,” or “I’d like to have sex with that hulk.” (I would guess there are about two thousand men who have thought the same, but two at most who would admit it.) But you’re supposed to want to kiss She-Hulk. You’re supposed to want to fuck her body.

Wikipedia:

Power Girl is the Earth-Two counterpart of Supergirl and the first cousin of Kal-L, Superman of the pre-CrisisEarth-Two. The infant Power Girl’s parents enabled her to escape the destruction of Krypton. Although she left the planet at the same time that Superman did, her ship took much longer to reach Earth-Two.

Possessing superhuman strength and the ability to fly, she is a member of the Justice Society of America and the team’s first chairwoman. Power Girl sports a bob of blond hair; wears a distinctive white, red, and blue costume; and has an aggressive fighting style. Throughout her early appearances in All Star Comics, Power Girl was frequently at odds with Wildcat, who had a penchant for talking to her as if she were an ordinary human female rather than a superpowered Kryptonian, which she found annoying.

Power Girl looks like this:

I will admit that I’ve got decades of training in this matter, that Marvel Comics and to a lesser extent DC had a major role in wiring my sexual desires from a young age. But the only honest response to a body drawn and framed in this way is to want to fuck it. Not because it’s appealing, though maybe for you or me or someone else we know it is, but because this body wants it, is designed for it, presents itself in such a way that can clearly send no other message. (There is no possible other reason for the tit window.) They really do call her Power Girl. The power they mean is not the power that they say they mean. This is an open secret.

It’s not that I have a problem with pornography. I support it. And my point is not that hero comics are sexist. (Though they are.) (I don’t think the point really needs to be argued.)

What fascinates me here is the total lack of self-awareness represented by She-Hulk. I can imagine another kind of She-Hulk: one with a body that matches her name. The character is immediately more engaging. (The dark crevices of her body. The way she would smell. The incredible strength. Her shadow on a wall like a pile of other shadows. Her voice; what would her voice be like? How does she feel? What does she want? Will she take what she wants?) But our collective imagination apparently cannot accept such a creature. The creators of She-Hulk raise the spectre of this other, stranger creature, a true hulk, and then they substitute this bikini model, never realizing the fact of their own substitution.

It isn’t that I think comics should stop being sexy. What amazes me, consistently, is the limitations of their erotic imagination. Superman’s body is arguably fuckable in some depictions, I think, though he goes to great pains to live an image so cold and hollow that no reasonable person would ever want to fuck him, most of the time; so are the bodies of some of the male X-Men, in the hands of a better artist. Most male heroes are wrapped in layers of muscle so thick, hard, crude, and ugly that the mere thought of hugging them repels.

This is cruel, even emotionally and sexually abusive, to the young male readership of hero comics, who would probably benefit from spending several minutes imagining warm, tender embraces with their heroes. (We imagine that the point of reading hero comics is to imagine yourself as the hero, but I would posit that it is equally or more common to imagine your father or your friend in the role.) These young men might benefit, indeed, from imagining enacting kindness on those bodies rather than super-powered brutality. We apparently need to be protected even from the possibility of the thought of our own homosexuality. Male heroic bodies must be grotesques, placed beyond the reach of our desire.

And female heroic bodies must appear safely and easily fuckable, though their bodies are ostensibly dangerous; Power Girl could tear off your head, She-Hulk could dismember you with no effort at all; their bodies must disguise these facts. Pillow-soft breasts, baby-making hips, and waists that you could fit your hands around, thumb-to-thumb and fingertip-to-fingertip. We fundamentally do not know how to imagine a heroic body for a woman. We are too afraid that the results might not be sexually pleasing. Or, perhaps worse, that they would be: that they might touch some primal, secret need.

Tags: comics, Power Girl, She-Hulk, super heroes, Superman, the Hulk

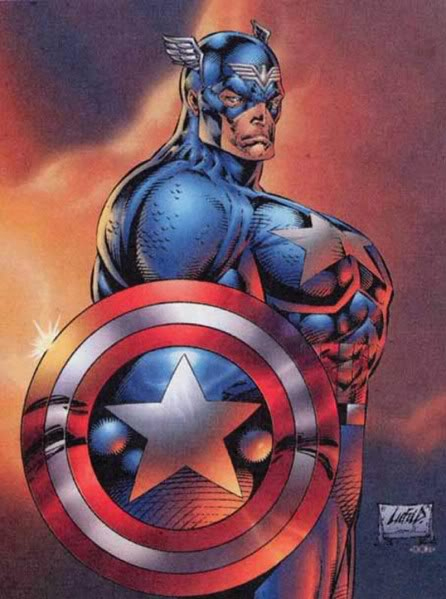

Rob Liefeld’s contribution to male body dysmorphia in comics is really fun when you look at how he likes to draw feat.

You hooked me, Mike. If your book explores half as many of the points you lay out above (We fundamentally do not know how to imagine a heroic body for a woman, etc), I’m sold. Excellent writing. Thank you.

Well, it’s fiction, so it does and it doesn’t. But yes. And thanks.

I like that young readers might benefit from imagining themselves hugging their favorite heroes. That’s an awesome point.

There are some “unsexy” heroines, but they’re there only for comic relief. I’m thinking specifically of Big Bertha from the “Great Lakes Avengers,” which is just jokes in jokes.

I also like that there’s this ur-She-Hulk somewhere in our imaginations, but before she can really draw us in to her insane form and eldritch visage, the creators swap her with a slightly muscular pin up model. We have the unspoken fantasy/desire/fear of the female monstrous, but when we have a chance to articulate it, we clam up and form a chain of substitutions that gets us as far away from it as possible.

There’s a good “argument” in comics about this in the Gail Simone Wonder Woman trade paperback for “The Circle.” In it, a warrior planet erects a statue to WW, but “pretties” it up to make it attractive like that planet’s females and warrior princesses, who are stout, with plated, manly muscles, protrtuding jaws, etc, etc, that look basically like most jacked dude heroes.

Now, what about villainesses, though? The Red Skull’s daughter, Sin, and her incarnations in the recent “Fear Itself,” while still with the boobs and thin wrists, wore a red death’s head face and was otherwise more “ugly” and hulking than your average superheroine. What do we do with our desire for the evildoers? Is it to substituted for something or do we just allow it because we can write it off as part of the enemy, which will be vanquished by the forces of good, restoring our heteronormative status quo?

This reminds me of a character in M. John Harrison’s “Light” named Annie. She’s a rickshaw girl, pulls people around all day in a Flintstones style human-powered vehicle, her body testosteroned and methed and sped (speeded?), etc. Sort of grotesquely powerful, though her power is more aligned with that of a horse or some beast of burden, but shaped squat and square, overpoweringly human smelling, and eventually becoming an object of sexual desire, though spurned (if I remember right) for a more typical ‘feminine’ character.

Physical muscles / brawn are already a stereotypically “masculine” symbol for strength, so fully implementing a female hero with those characteristics may begin to say something too disturbing about our idea of strength period.

That there is no true alternative to force, etc. Or conversely, that weaknesses are only physical.

I don’t think many people think this and I don’t think comic book stories believe this. But sometimes nuances that any human should be responsible for get funneled to female-coded characters. Not even characters, more like: the other pole holding up the tent.

speaking of liefeld, here’s this just for fun: http://www.progressiveboink.com/archive/robliefeld.html

I love that piece. Picking on Liefeld never gets old.

“I don’t want you looking at the stuff he’s drawing and think he’s a conscious adult male with a creative job who can and has influenced the minds of young artists. The man is a pair of blue jeans with a face. He has on a backwards cap, and when he turns it around, it’s still backwards.”

If your argument is that comic books are about exaggerations, then there’s no real reason to argue that. It’s a given. When it comes to the male body, artists in a number of media (comics and otherwise) have created male figures with comically proportioned muscles, jawlines, and penises. Comic books can’t be filled with giant penises, so that leaves the other two defining characteristics.

For women, exaggerated hips, lips, and boobs didn’t start with Power Girl, She-Hulk, or the comic book medium. The comic book industry isn’t doing anything that the Greeks, Romans, and Renaissance artists didn’t do in some form or another.

Also, reducing Power Girl and She-Hulk to fuckdolls is pretty reductive. The Power Girl boob window is unnecessary, but judging a woman by her clothes is unnecessary, too. If a reader is too busy focusing on Power Girl’s boobs to notice that she is one of the strongest heroes in the DC universe, then the reader might be the biggest “boob” in this situation. And a few writers have worked with this concept over the years.

She-Hulk’s transformation is not the same as the Hulk’s, and she isn’t a mindless beast like the Hulk. She shows more control than Bruce Banner ever did. Also, She-Hulk’s physique is considered “grotesque” by a large percentage of the population. Sadly, there’s still a large set of the population that can’t imagine how women with muscles could be perceived as beautiful. This argument pops up every Olympic year and every time Serena Williams wins a tennis tournament.

I’m not calling the comic book industry blameless at all. The sexism in the DC relaunch has been well-documented. However, to say that comic books are demeaning women in a new or different way is a stretch. Also, the average comic book reader isn’t an impressionable teen, but someone in his/her 20’s or 30’s. Mainstream comic books might be guilty of insulting their audience’s intelligence, but saying comic books are “cruel, even emotionally and sexually abusive, to the young male readership of hero comics” ignores the core audience for comic books.

As a comic book fan, I am also turned off and frustrated by stock representations of male and female identities, and that frustration comes from the fact the medium can do so much when it is allowed to do so.

It seems like we might disagree on some points, but thank you for writing about comics. Comics and heroism play a big role in my own work, so I’m always happy to see the genre discussed as literature.

I think it’s a bit of a dodge to describe the issue purely as one of exaggeration. Yes, men and women are both exaggerated — the men moreso, I would say — but the issue that frustrates people is that the genders are exaggerated differently. Men are stylized in a way that is designed to make straight boys and men feel powerful, and women are also stylized in a way that is designed to make straight boys and men feel powerful. There’s an extremely narrow range of pleasures available here, aimed at an extremely narrow range of people. Some people are upset that hero comics are pornography. For my part, I’m not really sure they can be anything else. And I don’t think there’s anything wrong with pornographic, even exploitative art — a lot of what I write is probably both. But hero comics could be smarter, better pornography that served more people, and more humanely.

I’ll admit I haven’t read a whole lot of Power Girl. What I saw generally winked at the audience along the lines of what you’re saying, insisting that she’s just an empowered woman who likes her tits big and her punches super punchy. And actually, here’s the thing: I kind of like Power Girl. Like I said, I grew up on this stuff! Power Girl gets me off. The best artists draw her with a curvy, muscular physique that works for me. And in a universe with a wider variety of body types and ways of being a woman, she would be a healthy addition. But the fact is that Power Girl, like essentially every other woman in the DCU and mainstream comics generally, presents herself in a way that is purely designed to appeal to straight men who want to imagine fucking her and straight women who want to imagine being her, getting fucked. Again, if there were a wider variety of characters, that wouldn’t bother me, I would be into Power Girl. I still am a little.

My claim isn’t really that hero comics are sexist or even that they are uniquely sexist; I think the former is self-evident, and you’ve agreed as much, and I think the latter is probably not true. Television is very nearly as bad on this count. My issue with hero comics is that they could be exploring so many more (and more interesting) modes of eroticism, desire, and humanity — that they direct themselves toward a particular set of straight people with a particular set of fetishes that happens to be especially galling because it privileges a dynamic wherein men are true heroes and women are, as you put it, “fuckdolls.” That’s pretty gross! And I think the damage that it does to men and boys is underrated; the inability to pursue emotional or sexual satisfaction, to make oneself vulnerable, to engage with other human beings as a human being is a nightmarish reality for a lot of men out there. Honestly, I’d rather be a fuckdoll: for all that I hate what characters like She-Hulk and Power Girl represent about gender politics, I identify with both of them much more easily than I do most of the male characters. I suspect a lot of male readers actually feel this way, and it’s just one more interesting erotic/human nuance that hero comics willfully ignore because the alternative is making a few frightened little boys feel gay.

Where is the tournament of bookshit? Or did that just die?

i never took heros seriously or had a personal hero besides like the unabomber