Random

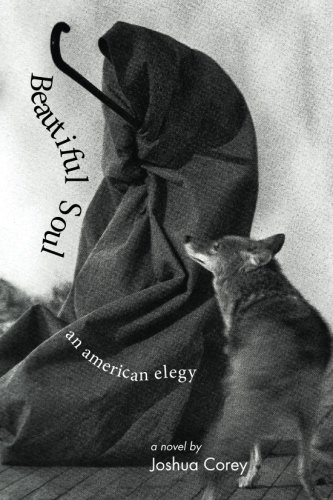

The Opening Pages of Joshua Corey’s “Beautiful Soul: An American Elegy”

Available now from Spuyten Duyvil

Because my home office has stacks on stacks of books, because new books are added to the stacks almost daily, because I have not finished half of half of the books I’ve started, I cannot grant attention to more than the opening pages of a book before I decide whether or not to stick with it. In truth, if a book has not convinced me within five or six pages that it deserves my complete attention I put it in the box labeled “To Be Traded At The Bookstore in Jacksonville.” Sadly, many many books end up in that box. Given the limited number of books that escape such a fate, I thought I might spotlight a few of them this summer in a series I’m calling “The Opening Pages.” Could have also called it “Books that didn’t end up in the trade box,” but that sounded less catchy.

Joshua Corey’s Beautiful Soul: An American Elegy did not end up in the trade box. Quite the contrary. I think it’s one of the most interesting and impressive books I’ve read lately. And since it has just been released, I thought it would be a great place to start this series.

In one of the blurbs on the back cover, Laird Hunt calls Beautiful Soul a “powerful novel” that “pays out its rewards gradually.” I agree with the first part, but disagree with the second part. From my perspective, Corey’s powerful novel pays out from the very first page.

BLACK SCREEN. A FLICKER. THE LETTER:

In the heart of the night the new reader lies awake with the lights turned off listening to the rain tapping on the skylight.

Is how it opens. Mysterious. Inviting questions from the very beginning. Am I the “new reader” or is “the new reader” a character? Am I looking at a black screen, a flicker, and the letter? What letter? The words following “THE LETTER” do not sound epistolary. There’s no address, no Dear so-and-so.

The fourth sentence is eight lines long and introduces a woman in bed (presumably “the new reader”), her husband asleep next to her, and describes what she would see if she were to open her eyes. All of a sudden the implication of the phrase “THE LETTER” morphs from an article of mail to a letter of the alphabet, as letters “like hieroglyphics” are “falling on her roof and the roofs of her neighbors.” Sentence seven begins, “Others too are awake reading the weather…”

So by the bottom of the first page I find myself transfixed by the seeming magical realism of what I’m reading. It’s so clearly rendered, yet also it feels so hazy, dreamy, liquidy.

As I turn the page I get eight lines down and stop dead in my tracks. Abruptly, yet somehow not jarringly, the perspective switches and I am met with this sentence:

The book is mine while I read it, for as long as I keep turning the pages, and once I am finished it dies to me but lives in the hands of other readers, and we might meet in a cafe or the supermarket or on a bus or in a hospital waiting room and discover, without title, that we share the same blind insatiable need for print, ants at the picnic, words printed on the insides and outsides of our eyelids, passwords, like canceled checks bearing signatures negated by the loss of value, the transfer of energy from beginning to end, unceasing until the book drops from my hand, I close my eyes, the rain spools, lurches, stops. Let me live here ever.

First of all, shut up. Those two sentence are badass companions. Aside from the aesthetic pleasure of abutting such a long sentence against such a short sentence, the rhythms and movements of the first are so richly complimented by the sharp and powerful brevity of the second. “Let me live here ever” he writes. Not “forever,” just “ever.” It’s a clever and subtle little act of defamiliarization. But that long sentence goes in so many directions it feels like a kite being yanked by a strong gust of wind or like a car that’s lost its ability to steer. That short sentence anchors it. Gives it a frame, a context. Gives it the full force of its desire.

But who is this new speaker? Is this Corey talking directly to me? Or, is it a narrator speaking to the reader or a character? Or…something else entirely?

The book’s second paragraph begins at the bottom of that second page and it, too, changes the narrative direction by altering the verb form. “Sleepwalking she might arise and dress and drive in the dark…” he writes. And by switching to the conditional (she “might” arise and dress, instead of “she arises and dresses”) the reader is spun again in another direction.

Spinning is probably a good visual for how I felt as a reader. Pleasurably spinning, to be sure, but spinning nonetheless.

At the top of page three we are spun yet again, this time with the imperative “Sit down.” Although I just used quotation marks to indicate the quoted text, the text itself is devoid of quotation marks. So at first I am not sure if the author or the narrator or the speaking voice is talking to me as the reader of the book or if a speaker is speaking to another character in the book or what. Soon I deduce that it’s dialogue, but this is not apparent and as the book progresses my ability to clearly identify the dialogue never really crystallizes, which I value positively in the sense that I enjoy being confused.

Little moments of confusion abound in this book. It’s opening pages are peppered with them. Corey switches from third person omniscient to first person singular to second person to first person plural to third person limited and back and forth and back and forth to the point where you simply have to shake your head in wonderment at the accomplishment of such an amazing feat. It’s as though he gave himself a challenge: can I use every available perspective within the first twenty pages of my book without losing the reader. I must say, he achieved it with aplomb.

Since I’m only focusing on the opening pages, I won’t elaborate on the 300-some pages that come after. But I will say, if I’ve piqued your interest but you’d like to have more to chew on before picking up a copy, check out Laura Carter’s insightful review of the book from a few months ago at Fanzine.

For anyone who enjoys the work of Italo Calvino, the narrative twists and metafictional interventions reminded me of If on a winter’s night a traveler. For anyone who enjoys the work of Claude Simon, the kaleidoscopic structure reminded me of Conducting Bodies. For anyone who enjoys Ben Marcus’s stuff, the personification or electrocution of language reminded me of his first three books. Many other comparisons, especially to the magical realists and to other novelists with the keen ears of poets who give enormous attention to the sentence itself, could be made; but honestly, the reason I was drawn into Beautiful Soul, the reason I recommend it to other discerning readers, is because of its irreducible singularity, which I classify as a hallmark of successful art.

As I say, pleasurable confusion awaits those who venture into Corey’s atmospheric debut novel. He’s already made a name for himself as an outstanding poet, and with this book I think he deserves to be equally recognized as an outstanding novelist.

Beautiful Soup, so rich and green,

Waiting in a hot tureen!

Who for such dainties would not stoop?

Soup of the evening, beautiful Soup!

Soup of the evening, beautiful Soup!

Beau–ootiful Soo–oop!

Beau–ootiful Soo–oop!

Soo–oop of the e–e–evening,

Beautiful, beautiful Soup!

Beautiful Soup! Who cares for fish,

Game, or any other dish?

Who would not give all else for two p

ennyworth only of beautiful Soup?

Pennyworth only of beautiful Soup?

Beau–ootiful Soo–oop!

Beau–ootiful Soo–oop!

Soo–oop of the e–e–evening,

Beautiful, beauti–FUL SOUP!’