Random

Using Biographies

In Peter Bien’s introduction to his biography of Nikos Kazantzakis — Kazantzakis: Politics of the Spirit, Volume 1 — he quotes (apologies: this gets meta pretty fast) Stanley Hoffmann’s review of Annie Cohen-Solal’s Sartre: A Life, in which Hoffman says there are at least four ways to write biographies:

“especially those of writers as monstrously prolific as Sartre. One way is to try to deal both with the events in their private and public lives and with their writings. In the case of Sartre, this would require several volumes and an author who would feel competent to handle philosophy, epistemology, novels, plays, screenplays, politics, literary and art criticism and psychoanalysis . . .”

“Another possibility . . . is to try to find in the works the expression . . . of the writer’s personal traumas and conflicts.” A third possibility is to discuss the works at least briefly and to show “their connection with the author’s and the general public’s concerns of the moment, without providing an extensive analysis of the content or indulging in psychological reductionism.” Lastly, one can leave the work aside and concentrate on the life. “It is, of course, a debatable choice. What is Sartre without his books?”

I find all four approaches useful in different ways. The broadly contextualizing approach is the most thorough, and when it is about a writer whose work is very much about an intellectual engagement with a time and place (i.e., the recent Deleuze/Guattari biography), it’s especially helpful. The second approach — the writer’s trauma in the work — is more appealing, but not as appealing as a fifth approach that I don’t see here, except in its opposite (the fourth): A biography that proceeds out of direct engagement with the work first, the man or woman second. I’m most interested in the writer’s life as it sheds light on the writer’s process, way of thinking about the work, etc. — the biography that sheds as much or more light on the work as it does the writer of the work.

Sometimes the path from here to there requires more of the other moving parts — the public context, the private context, etc. — because of the nature of the work. For example, Kenneth Silverman’s excellent Begin Again: A Biography of John Cage helped me understand the ways in which the work was in conversation with the work that came before, the conversation about music with Schoenberg and others with which Cage was engaged, and the special musical way of hearing percussive noises which helped Cage to overcome his frustrations with writing harmony (and which later helped him to hear them in a new way, and get to them by new methods of his own devising.) All of that is useful to the writer or the maker of any sort of things, not just because it amplifies or contradicts past readings of the made things, but also because it is invariably suggestive of possible future directions and processes for one’s own work.

Interviews are likewise helpful in these ways, and sometimes even more helpful, especially if the interviewer is interested in the thinking and making process rather than in superficial things.

What literary biographies, interviews, or other windows into the work would you recommend, and why? What do you value in them? Do you read them because they are interesting or because they are useful or both or neither? Maybe we can get some good things going in the comments thread below.

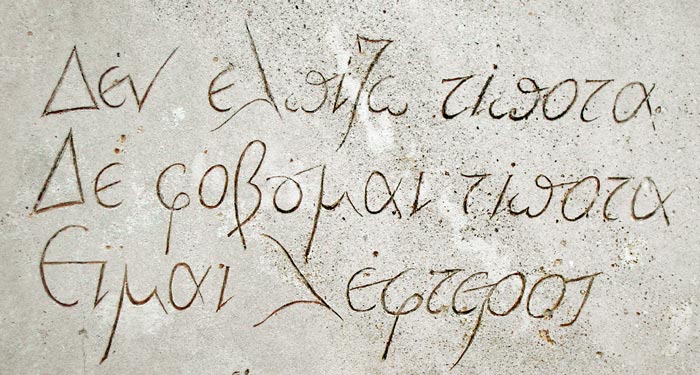

“I don’t hope for anything

I don’t fear anything

I’m free”

I think “biography” has three entwined responsibilities: the personal life; the work (books, say, or political intriguing, battles, voyages, whatever); and the world behind and before that particular life. A fourth facet or priority – significance – well, that’d be the effect of these three catalyzing orientations, were they presented ‘effectively’.

My favorite biography is Peter Brown’s Augustine of Hippo. – not that interested in late antiquity/early Christendom, not that interested in Augustine’s role in the history of Western philosophy (though he was a subtle and rewarding thinker indeed), don’t know much about trinitarian controversies, the Donatists, Pelagius, and so on — but this book is a beautifully written story of a life, the literary production of/within that life (in the intellectual context of its thought), and the world that formed and, in dialectical turn, was shepherded into its future by that life. It’s pretty long and composed in a scholarly way (deliberately argued, copiously footnoted, etc.), but Brown writes the story worldlily gracefully. Here’s a paragraph from The Lost Future (a chapter about the ten years between Augustine’s conversion and The Confessions; without succumbing to manichaeist duality, Augustine feels, with increasing intensity, the pulls of God’s (possessive and objective) love and temptation within):

[asterisks indicate Brown’s footnotes to Augustine’s texts there referred to or quoted]

chic-goods.com