March 4th, 2011 / 4:40 am

Random

Kyle Minor

Random

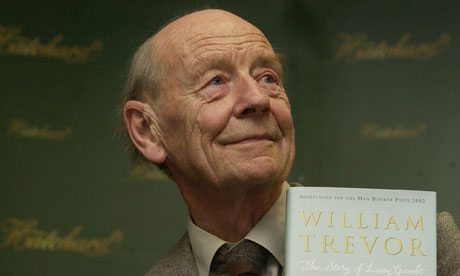

William Trevor v. The Idea of Experimental Writing

From the Paris Review interview:

No, I think all writing is experimental. The very obvious sort of experimental writing is not really more experimental than that of a conventional writer like myself. I experiment all the time but the experiments are hidden. Rather like abstract art: You look at an abstract picture, and then you look at a close-up of a Renaissance painting and find the same abstractions.

“You look at an abstract picture, and then you look at a close-up of a Renaissance painting and find the same abstractions.”

Which kinda misses the point, whether talking about experimental literature or not. If I choose to foreground language over the representation of language, I’m riding a whole other animal.

If you look at a piece of a page of a William Trevor book under a microscope, it looks the same as a piece of a page of a Gertrude Stein book under a microscope. So that must mean that Trevor and Stein are doing the same thing. Wait what.

really? the point he’s making is that the abstract painting is born out of the renaissance painting and a way of viewing, seeing, or re-seeing those paintings – not the other way around. he’s not saying renaissance painters were experimenting in the same way abstract painters are. he’s saying, with our hindsight, we can look back at the past and see these things now and compare and make further experiments. these re-seeings can inform both the experimental and the conventional now. he’s not saying his writing is anything like Steins, quite the contrary.

while i’ve enjoyed the experimental series, i’ve not posted any comments mainly because of the idea he expresses here. i’m much more interested in where the supposed experimental and the supposed conventional converge and where and how and why those terms break down.

also, @beardobees, what does “representation of language” mean? do you mean “representational language?”

Sorry, should have said the representation of language as a way of making meaning. The signified rather than the signifier.

I tend to think of ‘experimental’ in the same light I think of the phrase ‘indie’ in–back on Kitchell’s interesting post about the ebook web fic writers, a discussion popped up around what was ‘indie’ (as such discussions are wont to do on indie sites), and the same old dichotomy reared its head: indie as concept, indie as genre. I tend to assume, however, that it’s kind of condescending to point out to people who are working within the genre of Experimental literature (a genre with history and stylistic foregrounding in tradition) that ‘all writing is experimental’. It’s kind of like walking into a philosophy class that’s worked hard all year round, raising your hand, and saying “You know, maybe ‘good’ means something different from my perspective, dude.”

Which isn’t really what Mr. Trevor was doing, but it still seems kind of like pointing out the obvious to me. Maybe it’s important for someone to point out on occasion that there’s no a fundamental difference, but anyone who earnestly believes that the only ‘experimental’ literature is that which works within ‘Experimental’ constructs is probably beyond help, anyway.

So when he said “you … find the same abstractions” he didn’t mean “the same abstractions”?

So when he said “you … find the same abstractions” he didn’t mean “the same abstractions”?

vipstores.net

he’s saying “you look” at the thing and see those things. now. not “they” did. then. it’s a way of seeing.

good point.

good point.

alan, I don’t think Trevor is making – in this excerpt – a case for traditions that include both Renaissance and (20th c) abstract painting, a case for continuities that would indicate the ‘visibility’ of the Renaissance and the 20th c to each other.

I think Trevor is doing what Whatisinevidence is making fun of: saying that, if one limit a Renaissance painting to a small enough area of daubs and strokes, the picture won’t be resolvable into a representation of recognizable objects, but rather will be a picture of daubs and strokes themselves.

– and not to any disadvantage for Trevor’s wonderful fictions, but that ‘discovery’ of triviality is, as beardobees and NLY say, a missing of the mark and a trivial thing itself.

alan, I don’t think Trevor is making – in this excerpt – a case for traditions that include both Renaissance and (20th c) abstract painting, a case for continuities that would indicate the ‘visibility’ of the Renaissance and the 20th c to each other.

I think Trevor is doing what Whatisinevidence is making fun of: saying that, if one limit a Renaissance painting to a small enough area of daubs and strokes, the picture won’t be resolvable into a representation of recognizable objects, but rather will be a picture of daubs and strokes themselves.

– and not to any disadvantage for Trevor’s wonderful fictions, but that ‘discovery’ of triviality is, as beardobees and NLY say, a missing of the mark and a trivial thing itself.

It’s exactly this sort of misunderstanding that I aim to combat in my ongoing series, Kyle.

All trees are wood. All computers are plastic. These statements are meaningless. They tell us nothing about the differences between baobabs and aspens or pcs and macs.

Trevor’s example of looking closely at a Renaissance painting and finding the same abstractions as in an abstract painting is nonsense. At a subatomic level everything is the same, does this mean we ought not distinguish between water and arsenic?

Rubbish!

It is my contention that one’s ability to perceive difference matters significantly in terms of reading practices and writing practices. I understand Trevor’s point is to suggest that there are both overt and covert types of experimentation, explicit and implicit, but:

What good is it to say “all writing is experimental’?

Where do we get with such a statement?

What have we learned?

How does that help readers determine the most effective reading strategy when they pick up Burroughs’s The Soft Machine after reading Franzen’s Freedom?

How does that help writers think differently about the choices they make when they are making?

I very much appreciate you posting this, Kyle. It’s a great example of the sort of misguided doxa that compels my endeavor.

i suppose i took this as his main point: “I understand Trevor’s point is to suggest that there are both overt and covert types of experimentation, explicit and implicit.” i guess i don’t see him as truly believing that there’s no important difference between experimental and conventional – he’s simply making a case here for the idea that experiments happen in any type of writing, not that such classifications aren’t helpful when reading radically different texts.

i suppose i took this as his main point: “I understand Trevor’s point is to suggest that there are both overt and covert types of experimentation, explicit and implicit.” i guess i don’t see him as truly believing that there’s no important difference between experimental and conventional – he’s simply making a case here for the idea that experiments happen in any type of writing, not that such classifications aren’t helpful when reading radically different texts.

Except that it’s not meaningless to say that all trees are wood. Maybe I’m naive but I don’t find it trivial to explore the idea that all writing depends on experimentation. Commonalities seem important to understanding.

Except that it’s not meaningless to say that all trees are wood. Maybe I’m naive but I don’t find it trivial to explore the idea that all writing depends on experimentation. Commonalities seem important to understanding.

In this excerpt, Trevor puts all “experiment” on a continuum – from “obvious” to “hidden”, and suggests that all literature is somewhere on that continuum.

But he’s equivocating with the word “experiment”, isn’t he? What he means by saying that he “experiments” in a “hidden” way is that he tries new things – at least, ‘new’ for or to him – . But aren’t these writerly “experiments” themselves “conventional”? – are they not recognizably recognizable – pre-approved, as it were?

When people oppose “experiment” to “convention” – or somehow else differentiate them – , they mean that there are things (techniques, modes, etc.) that a community is prepared for, and challenges, denials, neglects, and so on of those things that that community hasn’t been made ready to assimilate comfortably.

Trevor is using “experiment” to describe his personal process of seeking new stories to tell and new-to-him storytelling means, but he’s ignoring – at least in this excerpt – how commonly accepted those means already are, however emotionally fresh his employment of them is.

Perhaps a more effective question than that raised by Trevor’s “obvious”/”hidden” “experiment” distinction is: has the (smaller) community of ‘experimenters’-in-writing grown its own conventions of acceptable experiment and become routinized and [gasp] boring both in its inclusions and its censures?

But Chris, it all depends–without noting the subatomic overlap between water and arsenic we might just think that there is no relation between the two of them, or we might think that solids and liquids and gases are utterly different entities, ontologically speaking, with no potential to transform into one another or interact with one another or yield some knowledge of one via the other. In other words, it does come down to your question about, “How does it help…”? But maybe it depends on your angle of approach. For readers being initiated into Burroughs, it makes sense to treat them as different species. For writers, though, who are making particles collide, maybe it makes sense to see the choices in a non-dichotomous manner.

Can’t stand Trevor’s stories, don’t like this mindset either. The term “experimental fiction” has to refer to, if nothing else, an experience of discovery in the reader, of aliveness and strangeness. Trevor’s work: Fucking boring. Dead. Didactic. If the term can mean anything — and it’s not an especially important term to me, but if it does have meaning — then Trevor is excluded.

Watching boring authors — as they so often do — attempt to appropriate the term “experimental” is just dreadful, embarrassing. He should write something interesting if he wants me to take an interest.

yeah i sympathize with trevor but disagree about the point because the problem i have with the term ‘experimental writing’ and the reason i don’t use it myself anymore is that most of its techniques can no longer be called experiments; in fact i think once something someone wants to treat as literature is published in any way shape or form it is, by default, no longer an experiment

‘experimental writing,’ while better than nothing, is a misleading term because it seems the whole idea isn’t actually about experimenting, it’s about practicing verbal written expression with a different view of what language and form should be made to do, it’s a question of how much they should inform the content, and it seems ‘experimental writing’ values language and form as means and ways of generating content; but this is not a foreign view, it’s just the view of poetry

yeah, i agree his stories are pretty bores.

Or how about those experimental techniques that have fallen out of favor because they’ve become so routinized or simply unfashionable that one dare not use them? Maybe metafiction just ain’t sexy in 2011. But if you show me your self-aware fictions, I’ll show you mine.

I think this kind of statement (Trevor’s that is) shouldn’t be so casually dismissed. A lot of “realist” fiction introduces nothing if not strangeness, though Trevor himself admittedly leaves me cold. However, the substrata of the statement is that to be less obviously experimental is not necessarily to be boring, as you state. And there does seem to be an exclusionary attitude among writers more obviously experimental towards writers who practice a more congenial discourse with tradition. An attitude that is as nonproductive towards reconciling questions of origin in creative endeavors as any kind of broad didacticism.

William Trevor is easily one of the most masterful English language writers alive today. The analogy is suspect; his skill is not.

I don’t think I disagree with you on your problem between Trevor and experimental literature, but I do on your point about the meaning of describing the act of writing as a kind of experimentalism.

On the example between 20th century modernist (let’s say cubist, for imagination’s sake) and Renaissance art, you’re entirely right to declare the analysis of a micro-view of abstraction in Renaissance work and a micro-view of abstraction in cubist art to be by nature flawed, it would indeed be of its critical viewpoint, and not descriptive of its surface appearance.

However, it is worth continually renovating our notions of the innate experimentalism of writing, as a particular linguistic render of life, of a certain hermeneutic relationship to being, at once embellishment, illumination, and derangement. Yeah, we should resist universalising critical approaches that then conceal experimentalism as it should be illuminated, but descrying experimentalism in the being of written entity, as opposed to the purely genric apprehension of experimentalism as formal experimentation, experimentation with methods of reading, layout, literary convention, so on and so forth, I think is worthwhile, and may be helped to begin by seeing writing itself as already tenusouly experimental, only to be entrapped by convention or context.

So, to reply to the questions on helping writers and readers, I think the two radically different positions on experimentalism aid them differently. Just thinking about the slightly condescending idea a clearer definition of experimentalism “helping” writers and readers, well Brecht intended to make of the theatre an education on how to “read” the experimental politics of the works enhoused, but is that work more experimental than Beckett’s Endgame, whose formal experimentalism is limited but whose major experimental contributions are “behind the form”? I don’t have an answer, I think they’re differently experimental. I don’t believe this is a cop-out, I think my critical position is better equipped to investigate them differently, and by nature should be.

Would I be wrong to read your response as endeavouring to highlight the Brechtian kind of overhaul of its own hermeneutic possibilities, its own audience, by the artistic act, as the kind of work needing to be separated from the conjectured experimentalism of more nebulous examples? I don’t think I disagree.