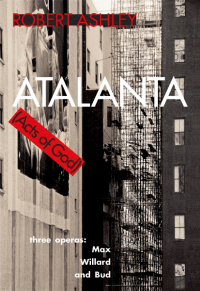

Atalanta (Acts of God)

Atalanta (Acts of God)

by Robert Ashley

Burning Books, 2011

208 pages / $25.00 buy from Amazon or SPD

24. When I began this review Robert Ashley was alive. In light of his death, I feel a compulsion to redraft and make these twenty-five points address something more. I want to talk about seeing Foreign Experiences and Lectures to Be Sung performed, about composition and improvisation, contemporary opera, and the intersection of music and language. Ashley’s work is full of good discussions. I’m attracted to the just-some-dude delivery style and storytelling aspects in the operas. One of my composer pals can’t follow the stories at all, and seems obsessed with the involuntary speech in Ashley’s work. Ashley’s work is so dense, and there are so many lessons that I take away from his work as a performer and writer. It’s hard to limit the discussion, especially given this kind of retrospective appreciation and the span of his work.

25. As I was struggling the the 25th point, I kept trying to figure out if there was some way I could articulate that reading Atalanta was very satisfying but also a little bit confounding. My mind kept wheeling around the opera, not the book. It wasn’t written for the page. The printing seems like an out of place artifact. In the afterward and in other interviews, Ashley seems to indicate that the libretto functions as only a part of a much larger event and set of processes. However, reading it I’m constantly dazzled by the turns the verse takes and the reading experience, which is so on its own terms. It’s really fucking good for being a kind of after-thought of a larger project.

1. Atalanta (Acts of God) is the first part in a trilogy of operas, the other parts being Perfect Lives, which is perfectly incarnated as a kind of YouTube/torrent masterpiece (completely amazing if you can get it), and Now Eleanor’s Idea. Atalanta was commissioned for performance in 1985. The publication of this book seems to coincide with the release of Ashley’s Atalanta (Acts of God)Volume II in 2010.

2. I have not had the opportunity to see Atalanta in production. Recordings are available. These recordings are of a completely different texture than the libretto/verse/text unperformed, and maybe are not my thing so much because they stick to a 72 bpm tempo in the recording and are much livelier in my head.

3. Atalanta (Acts of God) is a book of libretto, not a score, though a few songs have been included. It is not documentation of the production, though it does include notes, acknowledgments, and a handful of photos. The book is highly peculiar, in that it represents a kind of music based on collaboration, improvisation, and theater. All of which resist the book format, which seems more fixed, at least in my mind. There are some helpful notes and observations in the afterward.

4. It is easiest for me to approach Atalanta as a book in verse.

5. Ashley on writing for opera:

“The plot of the three (operas) doesn’t really have any meaning – it’s only a fancy category for catching a lot of things that are going through my mind. It’s not a very interesting idea in itself – an interesting idea would be like inventing penicillin or something like that – so when you say you’re going to write an opera about the history of consciousness in the United States, I mean who needs it?”

(106 The Guests Go to Super)

6. As anyone who has listened to a lot of Ashley’s work can testify, it is pretty impossible to get his voice out of your head as you read the words.

7. About the characters: Atalanta, the legendary Greek runner girl who is also the Odalisque, is wooed in turns by Max Ernst (famous surrealist), Willard Reynolds (Robert Ashley’s storytelling uncle), and Bud Powell (famous bebop pianist), though the recitation of anecdotes. A confused flying saucer lieutenant and captain drop in and comment on the would-be marriage. There are also some totally left field segues.

8. The plot of Atalanta is a skeleton for voices, ideas, and performance. It is a groundwork for piling narratives on top of each other. The dense accumulation of dialogue, incidental characters, and unidentified voices push the reader deeper into language which seems to focus on building moments rather than the progression of any kind of story.

9. From the afterward, all of the stories are enacted at the same time.

10. I have never seen a critique of Ashley’s work that focuses on women and sexuality. This seems like a glaring oversight, because Atalanta includes so many meditations about women and power, about a cultural impulse to control women, sexual perversity (briefly), courtship, domestic ritual, and young girls.

11. A really catty dialogue between a wasp-y sounding lady and a unidentified interlocutor regarding the selection of au pairs, fucked up (presumably Californian) parents, pills, and She-Ra costumed mutual masturbation.

12. Your-license-and-registration-please cop sex set in a Max Ernst engraving.

13. An ice skating monkey wearing human clothes.

14. Ketchup and tomato soup as a long con/major grift/rags-to-riches tale of commerce and the changing economic ordering of the post-Depression United States.

15. The geographical vastness of America and the languid progression of morphological processes that sculpt and mould the terrain.

16. Some of Ashley’s observations are incredibly subtle and only seem to be expressed in the reiteration of phrases in a pretty transparent way. At the same time, though the language is extremely simple and straightforward, one wonders exactly what’s being said, especially at key turns in the anecdotes. In Empire, there’s a brief excursion into a family history focusing on the narrator’s grandmother and aunt’s relationship to the itinerant railroad bums. They feed the railroad bums breakfasts without expectation, which causes controversy with his uncles.

“My grandmother would open the door without fear. That seems a strange thing to say now. The extra man would offer help around the house, meaning in the yard or garage. My grandmother would say that was not necessary. She would ask him to sit on the back steps and wait.”

Opening the door without fear, eating or not eating pie are, the indication of a passage of time; the emphasis is repeated, but the effect is vague, mysterious, and has the quality of the unsaid.

17. There is a relaxed spoken quality to language Ashley uses. It is casual and American, sort of lazy seeming. I find it extremely pleasant.

18.

“’…The law is sublime reason.’

I said, ‘You’re kidding.’

He said to me, ‘No, the ball bearing business has been smooth to me. It was my calling. My ball bearings are patented in my name. They are the best ball bearing in the world.’

Later I touched the work. It had nothing to do with maintaining life here on earth. I mean, the edges.” (20)

19. Character and voice become interchangeable in the telling of stories and dialogue. In some ways it is very easy to understand what’s happening, one just has to float through these excursions and shifts. However I suppose that if you actually think that something is going to happen, or be resolved in the telling, well it seems like that expectation will go unmet.

20. There’s this tension between the metaphysical/mystical, the sensual and the everyday, or rather a constant shifting between these avenues, which is incredibly hypnotic.

21.There is an extended discussion of vantage points, surfaces and edges, existing in time, the idea of scale, and language, or rather the qualities of these ideas. Again, there are not any pronouncements, but considerations and ways of thinking the reader is ushered into:

Long since, because facts of hearing had become, one supposes external facts more than internal facts, as if, previously, throughout the progress through what is called the past, because of its moment-to-moment-like meshing of the present, the world has changed, and there become more facts of hearing outside than inside; they were more external facts.

22. The realization that the Flying Saucer is really a bit of a stand in for time travel, reading, and memory. But the Flying Saucer seems to be symbolic/structural double for the reader: “And we are in the saucer./This is the myth?/The idea of the opera that was never seen nor heard. Is that the trouble …/In the saucer?/Is us.” I like that it’s always getting lost.

23. Ashley’s opera is often compared to Joyce in reviews. I suppose that in some ways this holds true, but I’m feeling a lot of Donald Barthelme, Gertrude Stein, and Robert Walser. Specifically, regarding Stein, I’m thinking of The Geographical History of America or the Relation of Human Nature to the Human Mind and The Making of Americans. Geography, lineage, America, vastness, get it? Ashley’s prose is joyful, sometimes solemn, also pleasantly goofball, never too aware of its cleverness. It also seems to float in its self-contained reality, hence the Walser comparison.

Angela Roberts lives in Oakland. She plays cello and writes a zine called Supertrooper.

Tags: 25 Points, Atalanta (Acts of God), burning books, Robert Ashley

Really glad to see this here—thanks!

About the only literary-critical take on Ashley that I’ve seen published is: Christian Herold, “The other side of echo: The adventures of a dyke-Mestiza-Chicana-Marimacha ranchera singer in (Robert) Ashleyland,” Women & Performance 9:2 (1997): 163-197. Herold is mostly talking about border/frontera identity viz. subjectivity in “Now Eleanor’s Idea.” He only briefly passes over singer Margherita Cordero’s sexuality, though, and doesn’t have much to say about the issue within Ashley.

It’s true that Ashley has been severely underserved by critics, especially by literary critics.

As you may know, Kyle Gann recently completed a book on the man and his work, which includes analysis of the opera librettos.