The Bhagavad Gita: A New Translation

The Bhagavad Gita: A New Translation

by Gavin Flood and Charles Martin

W.W. Norton, 2012

167 pages / $13.95 buy from Powell’s

1. The Gita is a 700-verse scripture which is excerpted from the Hindu epic The Mahabharata. The Mahabharata is the longest Sanskrit epic known to date. The Mahabharata is over 200,000 verse lines, totaling roughly 1.8 million words and is ten times the length of the Iliad and the Odyssey combined.

2. The introduction of this translated version quotes Philip Larkin’s poem “The Explosion.”

3. I have anxiety and decided I am going to read every religious text published this year. I have never read The Bible. I am going to.

4. This section of the Mahabharata is a conversation between a prince named Arjuna and Krishna. Krishna is God for all intents and purposes. Arjuna has to go into battle but it means fighting people he loves and Krishna is trying to get him to go into battle. It’s a tough break for everybody.

5. Arjuna and Krishna are basically arguing back and forth the entire time and I was nervous though that making this claim would be disrespectful to say, one of the oldest most important religious texts in history. I wrote to one of the translators of this book. He told me that he never thought of it that way and that there have been no studies on this theory but that I quote, “Might be right, might be onto something,” and that, “It is a really interesting theory.” Well that was flattering.

6. I picture Arjuna and Krishna on a basketball court going back and forth in each other’s faces arguing except they’re arguing about the disposition of man.

7. The underlying metaphor is of course the battle for the conscious, the battle for the soul, the battle on how to live one’s life.

8. Gandhi called The Gita “his spiritual dictionary.”

9. I felt better while reading this book.

10. In the book Krishna says the way to change yourself is to focus on breathing in and out. No-matter the situation, just focus on breathing and you will be changing yourself.

11. I tried to go to a yoga class once. My friend and I had been drinking earlier in the day and we were falling over and laughing so hard the entire class was horrified and the yoga teacher asked us to leave the room and never come back.

12. I tried to go to another yoga class five years later and my face was laying on a mat sideways and when I opened my eyes this boy next to me was laying his face on a mat and he was staring at me and then after class he asked me, “Who are you?” and I ran away and don’t know his name or anything like that.

13. I went to a yoga class in New York and the instructor came up to me and tried to reposition my hips and said, “It hurts?” and I said “Yes,” but I meant everywhere.

14. Some of the quotes in this book will make you cry, observe:

“Man is made of faith, Arjuna,

and man is the very faith that he has.”

15. I’m told that as a fiction writer I am at a great disadvantage for not having read religious texts because they are good examples of things such as human interaction, story and history.

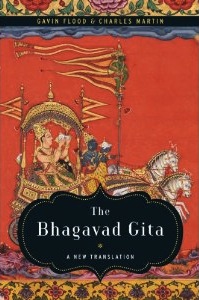

16. This book is about a guy who is stubborn.

17. This version is incredibly accessible and universally easy to understand.

18. Basically I’m like well Gandhi was cool, so…

19. I am interested that at one point the book basically says that women should be treated well because if they aren’t then they will have children of mixed race but I will ask somebody about that because well that one bothered me but maybe things were different in the 3102 B.C. which is when this conversation between Arjuna and Krishna happened, though some people are still arguing on when this conversation happened.

20. It’s really intense the way Arjuna had like the same problems in his heart that everyone has in their heart now.

21. You can read this thing in one day or night it’s only like 167 pages.

22. Also the cover art is amazing and apparently is an illustration that dates back to 1763 which apparently sits right now in the Virginia Museum of Fine Art, which, good acquisition.

23. I feel like making this version so easily readable for people was very Gita-ish.

24. It’s a very good narrative poem, this thing.

25. Namaste, OM, make love not war, etc.

Tags: 25 Points, Charles Martin, Gavin Flood, The Bhagavad Gita, W.W. Norton

cool, I’ve wanted to read this for a while, I like how casual your review is and I like the sound of the translation so I think i’ll PICK THIS UP. aka THIS REVIEW SUCCEEDED IN SELLING THE BOOK TO ME GOOD JOB.

I just read Crowley’s book on YOGA and it also implies the necessity of breath.

7. By “the conscious”, do you mean ‘the conscience’? or to connect the two — ‘awareness altogether’ and ‘conscience’ — by way of the difference between them?

19. “Race” — if that’s a word you’ve gotten from the translation or commentary — might mean ‘caste’, that is, not a (pseudo-)physical-anthropological category, but rather, a political-economic one. It might not be a skin-color — or whatever bodily marker of belonging — issue, but rather, an issue of what socio-economic class(es) one’s parents and their parents belonged to.

It also might be interesting, in the case of ‘racial’ difference — the case that “race” makes a difference — in the Bhagavad Gita, to consider the chiaroscuro shot through the text: arjuni [long ‘i’] means ‘silvery-white color’, and krsna [vocalic ‘r’ and lingual ‘s’ and ‘n’] is a plain Sanskrit word for ‘black, dark’.

You can see the skin-color difference between Arjuna (‘Silvery’) and Krishna (‘Black’) on the cover of your book: Arjuna is the chariot’s master; his apparent underling, driving the horses, turns out to be Krishna, eighth avataras [third ‘a’ long] (‘incarnation’) of Vishnu (‘the Preserver’ of the Hindu trinity of Creator, Destroyer, and Preserver).

There is controversy, in terms of “race”, about the entry of Indo-European speakers into Pakistan and north-western India. One idea is that Krishna looks like pre-Indo-European inhabitants of that area, namely, that his skin is quite dark, and that Arjuna looks like (represents??) the paler earliest Indo-European speakers to migrate south- and eastward into (and conquer) Pakistan and north-western India.

20., 24., 25. For me, the drive of the poem and its thematic fascination can’t be disentangled from the basic story: a warrior doesn’t want deliberately to kill his ‘cousins’ in battle, and a, what, version of ‘god’ convinces him to enter the battlefield murderously because all bodies die anyway, so there’s no difference, from the point of view of bodies, between killing and not killing. The poem subtly goes through the matter of ethics — of one’s responsibilities to others — , but it concludes (I think: unambiguously) in an extremely passive, even anaesthetized, way: nothing bodies do to each other has relevance from the perspective of real reality.

To me, the Bhagavad Gita is important and exciting because it makes the case compellingly for exactly what I don’t think is so.

I liked this review a lot and am going to read this translation.

In all illustrations, Arjun is the archer and Krishna is the charioteer. A man who has control over his mind is a charioteer who drives his own, unruly, mana (? will ?) and indriyani (senses). Arjun might sit higher on the chariot (actually, in other pictures, he sits BEHIND) but he’s not the one running things.

I find the black-white issue really interesting, because I see it as a form of skin-color dynamics that was possibly PRE-race, an interpretation separate in time and concept from the racist interpretations between Europeans and Africans.

‘Charioteer’ might be misleading: the guy with the reins to the chariot (for example, the darker-skinned figure in the book cover above) doesn’t decide where the chariot is going; he does what his master (the paler figure to the rear on the book cover) tells him to do.

( – something like the relation of the pilot of a ship–hand on its tiller–to its captain.)

In the picture on the book’s cover, Arjuna is behind Krishna.

The drama of the Bhagavad Gita is that Arjuna doesn’t want to fight the battle against his ‘cousins’ – he wants his charioteer not to drive his–definitely Arjuna’s–chariot into battle, and the charioteer–Arjuna’s underling–a) turns out to be not just a prince, but a chief god, and b) talks Arjuna (his ‘boss’) into fighting in the battle.

The warrior is socially superior to the – his – chariot-driver, but in this case, the charioteer, the advisor, reveals himself to be one of the greatest gods. Here’s how the intro to the first ‘chapter’ of the Gita that I have phrases the reversal of Arjuna and Krishna’s relationship (transl. Eknath Easwaran):

Oh huh. The things you learn.