Autobiography of a Corpse

Autobiography of a Corpse

by Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky

New York Review of Books Classics, 2013

256 pages / $15.95 buy from Amazon

In the beginning/ the Avant-Garde/ was just a silly thing/ Coconut-colored sidewalks/ Women with blue-white parasols/ tilting over backward/ or half backward/ in the beginning/ And then it grew, and became gigantic and hard/ Like a great, great stone, the Avant-Garde/ Like a great, great, stone that had usurped all of history—Kenneth Koch, One Thousand Avant-Garde Plays

1. The history of the 20th century avant-garde is a history of anxieties. And even as manifestos gave way to splinter groups, many things remained constant. A central tenant of this history came in the compulsion against modernity and the constricting social forces of advanced industrial capitalism. Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky wrote radical literary fantasia, and his work reflects many of the anxieties and themes that would develop across literary avant-gardes throughout the 20th century.

Born in Kiev in 1887, Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky moved to Moscow in 1922 where he worked as a lecturer and theater critic. From this time until his death in 1950, he secretly compiled an incredible body of fantastic novels and stories. These were not published in his lifetime, and owing to the damning soviet censorship, would not be published until 1989. This collection Autobiography of a Corpse, a selection of short stories was published for the first time in 2010, and an English edition came out from NYRB Classics in the fall of 2013. The collection, provocative and expansive, offers a look at many anxieties and themes that would come to define the avant-garde.

A primer on avant-gardisms.

2. Parvenu’s Conquer Moscow. For Krzhizhanovsky, Moscow was a site of promise and disappointment. The title story, “Autobiography of a Corpse,” tells the story of a man recently arrived from the provinces (to conquer Moscow!) quickly overwhelmed by the bustling city. To his horror, the modernization and mechanization of city life proved inherently anonymous and dehumanizing.

Life on the clock has long provided a source of modernist consternation — from Georg Simmel, “There is perhaps no psychic phenomenon which has been so unconditionally reserved to the metropolis as has the blasé attitude… The blasé attitude results from the rapidly changing and closely compressed contrasting stimulations of the nerves.” — to Robert Walser, “The metropolis contains loneliness of the most frightful sort…He can experience what it means to live in deserts and wastes…All he has to do is make himself unpopular among certain arbiters of taste…and in no time he’ll have sunk into the most splendid, most blossoming of abandonements” — to Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times.

The modern city, while stimulating, necessarily overwhelms, and to survive one must adopt a blasé attitude.

3. Tunnel Vision. Krzhizhanovsky explores the manner in which citizens of modern societies experience distortions of reality. In “The Collector of Cracks,” he focuses on places and phenomena that are generally ignored in everyday life. And in doing so, he highlights the paradox of necessary blasé attitudes and the political implications of “tunnel vision.”

He offers the paradox of “incorrectly supposed continuity of perception.”

“The object on which our eye is fixed seems to us to be continuously connected to our eye in all fraction of a second by a constant beam.” But this is not the case. An image may flash for only 1/50,000th of a second, and yet “remain in the eye for one seventh of a second.” As biological machines, we necessarily filter our experiences and impose inadvertent interpretations. We choose what we see.

Krzhizhanovsky identifies the way distortions in perception can lead to inhumane political decisions. He echoes the Frankfurt School, especially New Left darling Herbert Marcuse’s treatment of “One-Dimensional” society. According to Marcuse, societies of the 20th century trend repressive in ideologies of convenience and technological rationality. And the easiest way to live (somewhat pleasurable) also empowers the status quo. Worker’s move uncritically through their lives in pursuit of false needs, and any potential for humanist change becomes less and less likely: “The more rational, productive, technical, and total the repressive administration of society becomes, the more unimaginable the means and ways by which the administered individuals might break their servitude and seize their own liberation.”

4. Authoritarianism. By the time Krzhizhanovsky finished this collection in the middle forties, he had already borne witness to terrible political trends; and the pervasive blasé attitude he lampoons so well, had shown it’s dark side. In “The Unbitten Elbow,” Krzhizhanovsky describes the violence of a blasé society. In the story, an intellectual, Kint, responds in jest to an edition of the Weekly Review with a letter describing his project to “bite his own elbow.” The editors contact Kint, and the situation quickly spirals into absurdity, with Kint locked up in “A Hunger Artist,” type cage. Krzhizhanovsky ranks with the great absurdists (Beckett, Blanchot, Kafka) in his treatment of bureaucracy, philistinism, and the violence of a mob.

5. A Project of Imagination. In response to a blasé society, avant-gardists turn towards new potentialities. According to Marcuse: “Art breaks open a dimension inaccessible to other experience, a dimension in which human beings, nature, and things no longer stand under the law of the established reality principle…The encounter with the truth of art happens in the estranging language and images which make perceptible, visible, and audible that which is no longer, or not yet, perceived, said, and heard in everyday life.”

Or Allen Ginsberg: “Poetry is noticing what you notice.” Georges Perec, Raymond Queneau, and Julio Cortázar all framed their project as undermining the dominant logic of a repressive status quo. They sought to de-automatize readers through a diversity of tactics. This is the surrealist “Kick to the head” and, Krzhizhanovsky too, employs many of these tactics.

The Axolotl, a fantastical creature beloved by Cortázar

The Axolotl, a fantastical creature beloved by Cortázar

6. Horror. Krzhizhanovsky hones in on the essential absurdity of authoritarianism, and the terror he elicits is both laughable and disturbing. This humor recalls Chaplin’s Great Dictator, or Gregory Corso’s chilly: “Scary deaths like Harpo Marx.” In “Bridge Over the River Styx,” the frogs of the Styx clammer for a unification between the worlds of the living and the dead. Apparently, by the way things are headed, it’s not too far of a stretch, “The liberal appetite for wholesale slaughter only increased with the centuries. The liberals’ demagogic leaders vowed to make the waters of the Styx run red. Almost all frogs, down to the polliwogs, were won over by the propaganda. Swarms of spindle-legged tadpoles would hop up onto sandbars turn their thousands of mouths earthward, and cry: More—more!” The image of bloodthirsty frogs is at once goofy and creepy.

7. Uncanny. Krzhizhanovsky subverts the ordinary with the best of them. He employs the classic: small things as big. In “The Runaway Fingers,” a pianist’s hand gets bored and elopes, recalling Cortázar and Gogol’s marauding extremities.

And: big things as small.

In one of the most emotionally effecting stories in the collection, “In the Pupil,” a group of men reminisces about the moment each fell in love with an exceptional woman. These men have been shrunk and captured by this woman’s beautiful eyes. They now live together in her pupil as a tribe, with their surroundings resembling the bottom of a well.

8. Parable. In “Thirty Pieces of Silver,” Krzhizhanovsky presents twisting iterations of the fate of Judas Iscariot and his pieces of silver. The piece resembles satirical projects like Pasolini’s The Hawks and the Sparrows, Bunuel’s Simon of the Desert, or Bulgakov’s Master and Margarita.

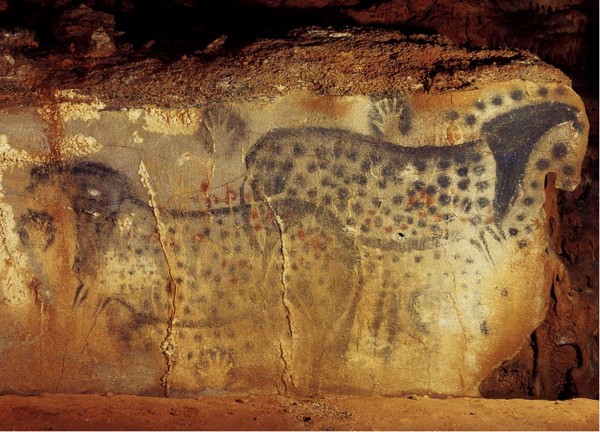

For some, the caves’ sensory isolational atmosphere is experienced as spirit-filled, even as hallucinogenic. For example, grotesque and hybrid cave images suggest a fusion between early consciousness and subterranean “entities.” It is as if the soul of an all-devouring monster earth could be contacted in cavern dark as a living and fathomless reservoir of psychic force.—Clayton Eshleman, Juniper Fuse

9. The Unconscious. The unconscious mind, and subliminal expression are an essential aspect of 20th century art. When considering the unconscious, Clayton Eshleman wrote, “Poetry…is about the extending of human consciousness, making conscious the unconscious, creating a symbolic consciousness that in its finest moments overcomes all the dualities in which the human world is cruelly and eternally, it seems, enmeshed.”

Maurice Blanchot regarded the unconscious as the total extension of the world and lamented this act of materializing thoughts and dreams. Krzhizhanovsky echoes this tension in, “The Land of Not’s,” a story that describes the constant push and pull between existence and non-existence.

10. Mixed media. Pastiche and heterographia permeate the collection. The titular, “Autobiography of a Corpse,” moves between a framed flashback, and a suicide note. Such tactics, including footnotes, encourage reconsideration and re-reading.

Anna Karina deconstructs hearts.

Anna Karina deconstructs hearts.

11. Paradox and dislocation. Burgeoning from Lautreamont’s “Beautiful as the chance meeting on a dissecting table between a sewing machine and an umbrella,” the Surrealists championed the revealing slip of the tongue or turn of phrase.

Zen Koans employ such paradoxes, like Roshi’s: “Zen is an elephant copulating with a flea.”

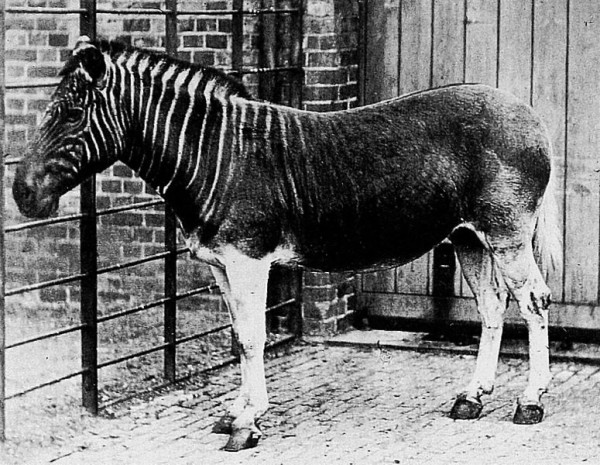

12. Bestiary. Like Borges’ Book of Imaginary Being’s, Krzhizhanovsky delights in strange and fantastic animals. He favors the Quagga.

The Quagga, an extinct subspecies of Zebra that lived in South Africa.

In his One Thousand Avant-Garde plays, Kenneth Koch reminds us, “A giraffe is more avant-garde, but an elephant is more surreal.”

13. Imaginary Language. Like Gombrowicz, Joyce, and Cortázar, “Autobiography of a Corpse,” features garbled words and phrases; again making the ordinary strange.

14. Found text. From Dada, to Fluxus, to LANGUAGE, found texts demonstrate that old avant-garde anxiety around authorship. In “Postmark Moscow,” a series of “found” letters tell a story, much like Kenneth Koch’s “The Postcard Collection.”

15. Censorship. There is always much to-do made around art and censorship in the Soviet Union. And this is, of course, justified. (Uncle Joe liked to stay up late editing plays) But the persistent emphasis on censorship under Soviet, or other explicitly repressive regimes, takes away from the reality of censorship in one-dimensional society. That is to say, it is very good in American politics to have a bogeyman counterexample of repressive censorship. Yet, in her terrific and devastating novel, City of Angels: Or the Overcoat of Dr. Freud, Christa Wolf poses the basic question: how can any speech in America be considered free? As political upheaval and revolutionary projects of the first half of the twentieth century faltered, societies became comfortable in their casual authoritarianism. Krzhizhanovsky dares us to imagine something better.

Tags: 25 Points, Autobiography of a Corpse, New York Review of Books Classics, Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky

great read, thjis. my only gripe (if you can call it that) is that i found so much of Krzhizhanovsky’s writing to be deeply funny. Black humor, Absurdism, yeah, but also the funny around the corner from them, a genuine sense of humor.

Plucked outta time and place he woulda done well, say, as a writer on the Simpsons.

“Christa Wolf poses the basic question: how can any speech in America be considered free?”

Because, unfortunate though it may be, being shut out of the market for holding certain opinions is still immeasurably better than being thrown in prison for the same?