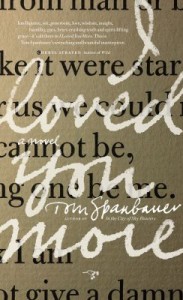

I Loved You More

I Loved You More

by Tom Spanbauer

Hawthorne Books, April 2014

468 pages / $18.95 Buy from Amazon or Hawthorne Books

I Loved You More by Tom Spanbauer starts with a slow burn, like an acid trip, of which there are a few in the book: There’s a preliminary period of seemingly aimless hanging out, and just when you start thinking nothing is going to happen, the room lights up, your heart lurches, and everything begins to glow.

Other writers have tried to quantify the transformation that occurs reading Spanbauer’s writing, the feeling of truth as opposed to artifice, the sense that now we’re really talking. The closest I can come is that it felt like letting air and light into a dark room. The book’s narrator, Ben Gruneberg says it much better, “When you get close to the vein that’s pulsing truth, when you open that vein, you can scrub your soul clean with the blood.”

Spanbauer is known for his truth-telling and open veins. He’s a gay writer and creative-writing teacher in Portland, Oregon, one of the gang of Portland writers of whom Cheryl Strayed and Chuck Palahniuk are the most famous, and Lidia Yuknavitch is the most beloved to me, personally. (Though, I don’t know if all these people are really a gang, or if that’s an outsider’s perception; I’m calling a Portland School, and assuming Spanbauer is a founder.) His Wikipedia entry says that he’s been living with AIDS since the 90s, and his AIDS book, In the City of Shy Hunters is a literary classic.

This latest novel, I Loved You More, published by Hawthorne Press in April 2014, is also a gay coming-of-age story, a living-with-AIDS story, and a story about male friendship, which seems to be mostly autobiographical. In it, Spanbauer’s alter ego, Ben Gruneberg—like Spanbauer, a writer and writing teacher with the same basic points of biography—chronicles his lifelong friendship with a straight male writer, Hank Christian, and the explosive end of that relationship. A bit of Google-digging will reveal a possible candidate for the real-life model of Hank.

On one level, it’s not a particularly dramatic story—a love triangle! featuring three writers! in Portland! and a pot of kale!—and how it all ends is mostly revealed on the first page. Moreover friendship is usually a side-story, not a main event, and devoting a book to the demise of one feels odd. The first section takes place in New York in the late 80s, when Ben and Hank are young writers at Columbia, studying under a fictionalized version of Gordon Lish, and their hanging-out, and the importance Spanbauer imbued it with, took a while to seize hold of me. And then it did.

Part of the alienation and then the magic is Spanbauer’s prose style, which is beatnik-ish in an old-fashioned way, using slang and refrains, a lot of fucking this or fucking that, man. His sentences are unconventional and fragmentary: “That old litany in this strange new place, how it made my heart stop.” Or this description of a leather bar: “In front of us, three men deep. Beyond, the bar is dark. Smoky dark. A foggy night, an ocean of men, dark waves. They have a sound, the waves, here and there bursts of pirate laughter, then no laughter.”

It occurred to me to find this lazy, but later the style felt essential, as did the book’s emphasis on friendship. Ben’s story was one of overcoming everything—his crushing mother and sister, his homophobic father and small-conservative-town upbringing, his early marriage to a woman, his own shame for being gay, his later fear and shame over his HIV+ diagnosis—and thus insisting on everything. When your story is all-wrong, truth is only thing you’ve got, and it comes in its own language, at its own pace, possibly without conventional sentences or the commercial narrative arc insisted on by mainstream book publishing (imagine that!). Ben is a gay man who loves a straight man, and they’re just friends, and not even particularly enlightened friends, but the type who can each get sick (Ben with AIDS, Hank with cancer) and be too shamefaced to even call each other, just like men, for twelve years. Sometimes that’s what love looks like.

Here’s one of Spanbauer’s most searing passages: “Seven years married, spiritually dead is right there again, right in my face, ready to devour me again. No longer a line around me that says this is me, this is my space, and you have to acknowledge this space because it’s sacred and that line has to be there because it took my whole life to set up that line and without it I cannot exist.” [Emphasis mine]

This is a book about taking your whole life to be able to tell your own love story—not the one you are supposed to have, but the one that is yours—and then telling it as truthfully as possible.

After the passage quoted earlier about opening a vein and letting truth pour out, here’s what Ben says next, describing anal sex to Hank (who asked, but possibly didn’t really want to know), on a New York City street, one very early morning a long time ago:

“‘Suddenly,’ I say, ‘my ass sucks in his cock as if his cock is life and I’m a dying man. Fucked me like I’d never been fucked. A fist jammed through my burning ass, reaching up to my heart, holding on tight, cradling me like a baby. Everything is exploding. Merge. There’s no other word for the way I come.’ … Hank doesn’t blink. The way his black eyes look, I know something’s changed.”

It’s a beautiful example of choosing truth over fear—of a character saying the scariest and most raw thing he could. As a culture, we’re scared of sex, we’re scared of being ridiculed when we talk about sex, we’re scared of male penetration, especially a man desiring it (“my ass sucks in his cock” ), we’re scared of emotion attached to graphic representations of sex (“reaching up to my heart”), we’re scared of our infant-selves (accessed during sex!?!), we’re scared of merging, of admitting we felt merge-y, we’re terrified of judgement…. All of that, yet Ben speaks anyway.

Spanbauer is equally, painfully frank on living with AIDS, and on sexuality and age. He goes digging for Ben’s worst fear and finds Catholic-boy horror-visions of a worst self twisting in hell—a vision that’s ultimately human, normal and reassuring. The cumulative effect is a bravery high, that starts slow and becomes ecstatic.

It’s difficult to pick a favorite part, in a book where I had so many. A description of being depressed as having a “charcoaled soul.” Three people fighting and crying outside in the rain. Old people, old bodies, disease being treated with respect. A balding, purple-haired man with a glass eye and tumors getting the girl. This statement about AIDS: “The way it eats at your brain, when you sit quiet you can actually hear the virus in your head.”

But if I had to pick it’s possibly a funny one, of Ben returning to the East Village in New York City, (the descriptions of New York throughout are superb), and finding so much of it gone and changed. He’s staggering around, remembering a city I remember too, looking with horror at the New York I now know. He goes back to his favorite bar on the West Side Highway, and sees, “From out of the bones of the building that used to be the Spike, a strange new tower has risen up and out, shiny bright. Another spaceship that’s set its ass smack down on my history. Aliens from spaceships man.” And later, “Aliens man. Billionaire aliens.”

I walk around New York City now and think of Tom Spanbauer often, for his bravery and truthfulness. And then I laugh at the billionaire aliens.

***

Valerie Stivers is a reader for The Paris Review, and is blogging about every book she reads in 2014 at www.anthologyofclouds.com. Her journalism has appeared in The New York Times, Elle, Flare and many other publications. Most recently, she was an editor at Yahoo!

Tags: I Loved You More, Tom Spanbauer

[…] This post was originally posted on HTML Giant. […]