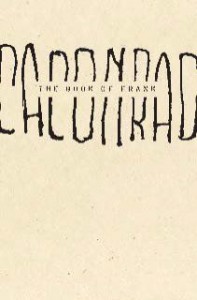

Frank. Yes, he’s that, ribald but also delicate—a reactionary event if only for being born. He’s the subject of CAConrad’s The Book of Frank, first published by Chax Press and freshly picked up by Wave Books, who have padded it with additional poems and a glowing Afterword by Eileen Myles. Despite steady output from Conrad, the book’s creation took over a decade.

Frank. Yes, he’s that, ribald but also delicate—a reactionary event if only for being born. He’s the subject of CAConrad’s The Book of Frank, first published by Chax Press and freshly picked up by Wave Books, who have padded it with additional poems and a glowing Afterword by Eileen Myles. Despite steady output from Conrad, the book’s creation took over a decade.

These are not persona poems, but I’m still curious about the distance between the repressed, ever-morphing Frank, and the poet, so easy in his skin, disarming. I saw CAContrad reading at St. Mark’s Poetry Project this fall: there’s the characteristic nail polish, glittery and red; a wooden Chinese fan sways from his fingers. As he begins, a gladiola leaning against the podium begins to fall. But Conrad catches it. “This is a very unruly gladiola,” he adds, moving on to the next poem with the bloomy staff clasped in hand.

You could say Frank is an unruly gladiola of a being. Or picked over, anyway. Rejection begins at birth: “why doesn’t my son have a cunt!?” Immediately the hems of this strange world emerge full of teeth—here are Kafka’s anxieties, Ginsberg’s bodily exclamations, Lorde’s iridescent witnessing. Above all I am reminded of Russell Edson’s prose poems with their cannibalistic domesticity and that damnable supper table. But unlike Edson’s march of weird worlds that grow out of fairy tale and seem to gesture a French Surrealist shrug toward real-world correspondence, shrugging is not easily done. Hero or anti-hero, he remains with us for 144 pages, developing and driving many a stake into the ground of human suffering: shame, envy, rejection, lust, violation, you name it.

At first glance, Frank is gaudy—on level with a Garbage Pail Kid, complete with booger-on-finger. But his pain has a convincing form to it, and yes, he is a sexual being. With soulful repetition, Frank’s shrinking away from the world becomes a form of transformation. His skin turns with the autumn leaves. He dies by freight train or when a mailman’s indelicate hands crush his soul in an envelope. Thankfully, these transformations are not mere devices to get out of the poems. Rather they are Frank feeling for the right exit—one that leads to free expression. And it doesn’t have to be Virgil leading the way if a fallen fruit cup will do:

…he looked under the table

saw how people touch themselves

even at dinner parties

zippers stroked

knees re-acquainted with palms

his eyes clouded in jubilation

“but where is Frank?” they asked

while on their laps

the only answer

was a tiny

mysterious

violet

If The Book of Frank truly were a book of the bible, then would Frank be the voyeur apostle, peeking under the table during the Last Supper? One can only imagine. Wherever he is, discovery comes by inventive escape. This movement is not prayer or pity. It’s an attempt to flap without wings. In these poems there is no perfectly humming answer, figured in image or epiphany or political discourse, that will succor those rejected on the basis of gender, sex, what have you. But look: we do have humor, witness, and imagination.

Each poem of the book is unnamed, lending to a blurring effect, though first lines tend to announce themselves. Often poems open with a simple noun + verb formula, from which point Frank either acts or is acted upon. Or, as happens with great directness in these tercets, Frank acknowledges his act:

Frank ate clear around

the sleeping worm

of the apple

“Any life saved in this place

is magic” Frank said

“its life coming back to you”

Of course the ‘worm’ here could be cheeky, but it is also life that is observed rather than corruption. The “life coming back to you” is the book’s obsession. What is strange should not be beaten back, the youthful Frank observes. But, Frank ages:

Every night

Frank dissolves

Into the sheets

Not a man

But a stain

His wife rubs him

back to life with

her early

morning

vagina…

It’s eerie how ‘man’ and ‘stain’ slant rhyme so comfortably, no? The older Frank has become more complicit with a brutal world through a set of compromising domestic conventions, especially considering that he is clearly gay. Frank’s dissolving appears to be pathetic dependence: annihilation. But wait. Continue reading the poem and you find that a dog and Frank dissolve together, and in the end we see: “Frank with child / at last!”

Humor steps in, turning what is sorry and hopeless into an absurd miracle. Many of these poems do this, crackling with humor. Often when literary types talk about a poet being funny, they are really talking about a kind of wit: an ability to expose absurdity very subtly, without producing much of a grin. It often seems that poets with a vocal sense of humor tend to get overlooked a bit—unless they are dead Latin Satirists.

I can imagine CAConrad going on writing endless manifestations of Frank, and the poems continue to hum. How to find the right exit or end? When Frank trails off on a dandelion seed, we can guess that at least a weed—such a harsh name—will plant. These poems should be approached many times, each time the reader bringing a little monstrosity, a little queer, a little dreamer to the table.

***

Brandon Lewis teaches, writes, and lets his beard grow in Brooklyn. His poems are found in Fifth Wednesday, Poet Lore, Harpur Palate, and Oranges and Sardines.

Tags: CAConrad, the book of frank, Wave Books

Loved this review of one of my favourite recent books of poetry… thanks.

Great review for a fantastic book! I encourage everyone to buy it and read it. You won’t regret it. Trust me, you don’t want to die without having read this book. You will have wasted your life.