25 Points: The Alligators of Abraham

The Alligators of Abraham

The Alligators of Abraham

by Robert Kloss

Mud Luscious Press Novel(la) Series, 2012

214 pages / $15 buy from SPD or Amazon

1. Alligator: Non-commissioned submarine, completed Spring 1862 by Union Navy. Length: 14.3m. Speed: 2-4 knots. Crew: 8. Missions: Five, failures. Abandonment: Its tow ship, the U.S.S. Sumpter, cut it loose during a storm off Cape Hatteras, NC. Remains lost.

2. Abraham Lincoln visited the Alligator during its testing phase. Brutus de Villeroi’s initial design required paddle propulsion, which was later replaced by a central screw propeller.

3. (The American Annual Cyclopedia and Register of Important Events of the Year 1891): “One steamer, the ‘Louvre of Paris,’ was built and put on service [using a central screw] between Paris and London. She made a very good record for herself for nearly a year, but was unfortunately wrecked, through no fault, however, of her peculiar construction.”

4. When the alligators finally appear and begin devouring people about halfway through RK’s novella, I did one of those disorienting Google/library searches on whether a plague of alligators really followed the Civil War anywhere in the coalescing Union. I found the Alligator instead, and I couldn’t separate it from the flesh gators in the book. A plague of hungry submarines.

5. Matt Kish’s drawings are toothy reptilian sprawls of overlapping flesh and machine, gaping mouths in the process of being perfected.

6. The General, Alligators of Abraham’s marauding patriarch, shifts his bloodlust, augmented by grief over a son dead from typhoid and a suicided wife, into (self-)mutilating industry. Into a necrophilic fixation on embalming his body while still alive, and living inside the bloated corpses of alligators. Into pathetic need: “I need you here by my side. I fear I may destroy us all” (to his second son, after a second wife has left him). Into merging his sons’ identities, never naming the composite dead/alive child he (and the book) regards as you except to call him by the dead boy’s name, Walter.

7. Old Testament-fueled American novels of war rage relegate women to drawing rooms, brothels, graves, sanitariums, rumors, away. The second wife inspects a private room the General has customized for her, and says to son and husband, “Will the both of you just leave?” As if I can’t be in this room if you’re watching. And after she has packed and gone, the General says to his son, “If she weren’t gone already, I would kill her.”

8. “And your father lit kindling beneath his tin tub while infant alligators darted within, and soon the slow boil of water, and your father said into the absence, ‘I believe their hide impervious.’ And when these alligators bobbed lifeless in the bubbling, your father said, ‘They must become stronger with time.’”

9. (This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War): “Redemption and resurrection of the body were understood as physical, not just metaphysical, realities, and therefore the body, even in death and dissolution, preserved ‘a surviving identity.’ Thus the body required ‘sacred reverence and care’; the absence of such solicitude would indicate ‘a demoralized and rapidly demoralizing community.’ The body was the repository of human identity in two senses: it represented the intrinsic selfhood and individuality of a particular human, and at the same time it incarnated the very humanness of that identity—the promise of eternal life that differentiates human remains from the carcasses of animals, who possess neither consciousness of death nor promise of either physical or spiritual immortality. Such understandings of the body and its place in the universe mandated attention even when life had fled; it required what always seemed to be called ‘decent’ burial, as well as rituals fitting for the dead.”

10. Nobody in this book is decent. READ MORE >

February 12th, 2013 / 2:21 pm

25 Points: The Bhagavad Gita

The Bhagavad Gita: A New Translation

The Bhagavad Gita: A New Translation

by Gavin Flood and Charles Martin

W.W. Norton, 2012

167 pages / $13.95 buy from Powell’s

1. The Gita is a 700-verse scripture which is excerpted from the Hindu epic The Mahabharata. The Mahabharata is the longest Sanskrit epic known to date. The Mahabharata is over 200,000 verse lines, totaling roughly 1.8 million words and is ten times the length of the Iliad and the Odyssey combined.

2. The introduction of this translated version quotes Philip Larkin’s poem “The Explosion.”

3. I have anxiety and decided I am going to read every religious text published this year. I have never read The Bible. I am going to.

4. This section of the Mahabharata is a conversation between a prince named Arjuna and Krishna. Krishna is God for all intents and purposes. Arjuna has to go into battle but it means fighting people he loves and Krishna is trying to get him to go into battle. It’s a tough break for everybody.

5. Arjuna and Krishna are basically arguing back and forth the entire time and I was nervous though that making this claim would be disrespectful to say, one of the oldest most important religious texts in history. I wrote to one of the translators of this book. He told me that he never thought of it that way and that there have been no studies on this theory but that I quote, “Might be right, might be onto something,” and that, “It is a really interesting theory.” Well that was flattering.

6. I picture Arjuna and Krishna on a basketball court going back and forth in each other’s faces arguing except they’re arguing about the disposition of man.

7. The underlying metaphor is of course the battle for the conscious, the battle for the soul, the battle on how to live one’s life.

8. Gandhi called The Gita “his spiritual dictionary.”

9. I felt better while reading this book.

10. In the book Krishna says the way to change yourself is to focus on breathing in and out. No-matter the situation, just focus on breathing and you will be changing yourself. READ MORE >

February 7th, 2013 / 1:15 pm

25 Points: Uncreative Writing

Uncreative Writing

Uncreative Writing

by Kenneth Goldsmith

Columbia University Press, 2011

272 pages / $23.95 buy from Columbia UP

1. Uncreative writing is situating. A détournement. A patchwriting. Goldsmith: “context is the new content.”

2. A portrait of Stéphane Mallarmé with “A Throw of the Dice” inserted three times:

3. Uncreative writing is language as pure material. Quantity over quality. The digital-age inheritor of Stein, Concrete Poetry, Mallarmé, Herbert, Apollinaire, and L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E. It sees the internet as language abundant, language swim, all text thrum. Goldsmith: “What we take to be graphics, sounds, and motion in our screen world is merely a thin skin under which resides miles and miles of language.”

4. Much of what Goldsmith says uncreative writing is is stuff I already know. Through Flarf, through FC2 and Les Figues Press, through Goldsmith’s own work like Day or Traffic or Sports, through Walter Benjamin and Gertrude Stein and Vanessa Place, through this blog, through Ron Silliman’s blog, through David Markson, through any number of conceptual writers working today.

If you’re familiar with these things too, you’ll nod your head and move along through a number of the early essays here. If you’re not familiar with these things, this book’s a solid place to begin.

5. But I’m not sure Goldsmith thinks he’s saying anything radically new with these essays as much as he’s articulating (again) a stance toward language that should be obvious to anyone writing, but still, for some reason, isn’t.

A sense of perplexity—maybe even frustration—about a large segment of contemporary writing runs through the early essays here.

Goldsmith wonders: What happened that made most 20th and 21st-century writers miss the work of Duchamp, LeWitt, and Warhol? Why did conceptualism take off so readily in the visual arts and not in the literary? What is taking writing so long to mine the possibilities of the conceptual text? What’s with all the holdover from literary Romanticism? The stuff about genius? The stuff about ego and originality? All that stuff about having a voice?

Still worthwhile questions.

6. Here’s Goldsmith’s annotated copy of Charles Bernstein’s “Lift Off,” a piece of uncreative writing Bernstein built by transcribing the characters from the correction tape of his manual typewriter.

Here’s a recording of Goldsmith performing it.

I like this poem because it’s hard to see it being made today. I like this poem because of its impossibility.

And I like Goldsmith’s performance of it because, even with all that, he shows how the thing’s still legible.

7. When’s the last time you typed another writer’s story word for word?

8. Picasso’s Portrait of Gertrude Stein with excerpts from The Making of Americans inserted: READ MORE >

February 5th, 2013 / 12:09 pm

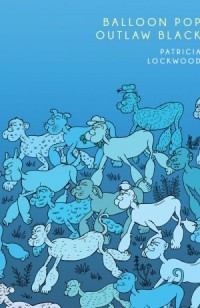

25 Points: Balloon Pop Outlaw Black

Balloon Pop Outlaw Black

Balloon Pop Outlaw Black

by Patricia Lockwood

Octopus Books, 2012

104 pages / $12.00 buy from Octopus Books or SPD

1. “Popeye.” The protrude of oldest skin, the swell of the part that sees.

2. “TITLE FONT SET IN CHAMPAGNE & LIMOUSINES.”

3. “Regarding ink, why black? Black because something was extinguished there?”

(When We Move Away From Here, You’ll See A Clean Square of Paper Where His Picture Hung)

Lines. Black Lines, (Saying those words out loud to myself makes me think of Lockwood’s Octopus partner, Ben Mirov, and his Black Glass Solioquy), are so important to Balloon Pop Outlaw Black (to every text) and to the powerful, self-conscious nature of its “drawn” characters. They are how the cartoons come to appear into their paperflatbookflat, but moving “Popeye” worlds. They are what all of our poems are b(l)oated with and lifted with and broken up by.

4. I forgot my razor in Minnesota, so there are small black lines coming out of my armpits and legs right now. I hesitated the first time I bought a bra that was black. Do you remember when that meant [inside of a Ten Things I Hate About You cultural map] that you were aching to have sex with whatever boymachine? I sat behind a hot girl named Sara in a history class and saw black lines coming out of and through the material of her white Calvin Klein t-shirt. I believed that it was those lines that made boymachines popeye and pupeye across the cover of yearbooks like “blueprints of bulls” (Killed With An Apple Corer, She Asks What Does That Make Me).

5. Now I believe all of your underwear is made of glowing and changing moodring material.

6. It is black lines, night letters, dark lines, definite lines that create and strong arm identity here in this text, that attract all words and beings of this dynamic hair forest together into their lonely, swallowing on swallowing world.

“The dimension is a coat; it is flowered on the green ground. The cartoon wouldn’t wear it if

his mother didn’t force him” (The Cartoon’s Mother Builds A House in Hammerspace).

7. In BPOB, however, lines become, are pushed brilliantly to be, what also gulps identity up, what bruises it around. It’s beautiful burst. It’s hammerwriting.

Elisabeth Workman, mentions a quote by Lisa Robertson inside her Cuntos Manifesto that feels imperative every time I re-read Lockwood’s poems and every day I make toast, “Identity is very ungenerous and completely non-erotic.” The characters here, the speakers here, want to allow themselves to fall apart while engulfed under the speechlove of another dark line or person or word as it invades and saturates and distorts them into bigger better. It think it is the best picture of a galaxy.

8. “And it’s hard to tell where the house ends and her insides

begin, there is so much inside around her”

(The Cartoon’s Mother Builds A House in Hammerspace).

9. “How can she always arrive at him?”

(The Cartoon’s Mother Builds A House in Hammerspace)

10. Lockwood’s characters: a whale, a boy, a mother, a father, a she, “Popeye”, a he, crawl at us and at each other with cartoon mouths and cartoon chests. They aren’t comic books. Their muscles are not hyper-masculine or hyper-realistic. Their muscles look like little bumps on the page. Cartoons brush against almost being pathetic constantly, just like we/I do. It’s what is funny. And it is what makes so much room for interesting there and in BPOB. READ MORE >

January 31st, 2013 / 12:08 pm

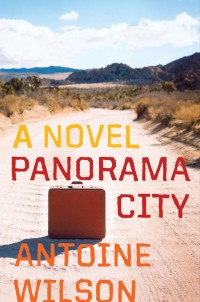

25 Points: Panorama City

Panorama City

Panorama City

by Antoine Wilson

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012

292 pages / $24.00 buy from Amazon

1. Panorama City is narrated by Oppen Porter, begins with the death and burial and unburial of his father, deals much with working in fast food restaurants, a suspect Christian coffee shop, and a beautiful psychic; the book primarily chronicles a forty day period when Oppen lived with his aunt in Panorama City. There is something Biblical about it.

2. The book is a monologue. Each section is divided up into paragraphs. There is a space between each paragraph. Oppen, on what he expects to be his deathbed, is trying to record his collected experience for the benefit of the son he is about to have. He is talking into a cassette recorder; you can tell he is talking very fast, through nearly the whole book it seems like he is going to run out of air.

3. The sentences in this book sprawl, stretch, snap, expand, loop, twirl, and collapse back in on themselves like exploding stars.

4. There is a scene in which a character falls through a ceiling. It is probably worth reading the whole book just for that scene.

5. Usually when people say that a book demanded to be read, or reached out and grabbed them by the throat, or got them in a chokehold, or some related metaphor for attention-grabbing, I shrug my shoulders. Not every good book demands to be read. In fact, a book has never demanded for me to read it—and this is what is cool about books. They’re not loud; they have no quirky camera cuts. All books, at least those in traditional form, are handheld, but unless you have gotten your book very wet the text stays exactly in the same spot on the page no matter what angle from which you look at the book. This is good.

6. Panorama City split me open. It is full of beauty; it is full of truth. I think John Keats would’ve liked it.

7. This book demands to be read, #5 be damned.

8. I’ve heard that one of the main pleasures of reading good fiction is that of recognition but I haven’t heard many people express that it can be one of the chief pains of reading fiction, too. I felt like the book was examining me.

9. This book is full of characters that spout what seems like cheap wisdom that instead actually turns out to be pretty fucking wise. Oppen Porter should speak for himself:

10. “The revelation of an eternal soul should occasion drinking of beer and looking at the sky, Paul’s words, because word eternal means, above all, that we have time.” I wish more religious people would realize this. I wish I could realize this. READ MORE >

January 29th, 2013 / 9:09 am

25 Points: The House with a Clock in Its Walls

The House with a Clock in Its Walls

The House with a Clock in Its Walls

by John Bellairs

Dell Publishing, 1973

179 pages / buy at Powell’s

- I first read this novel when I was a kid, checking it out from the library. Actually, I first read John Bellairs’s novel The Treasure of Alpheus Winterborn (1978), which I picked it up because of its Gorey cover and illustrations. And it’s through these novels, I think, that I first learned about Edward Gorey.

- I got my current copy of THwaCiIW from my friend Rebekah, last November, at her Friendsgiving party. And it’s only appropriate that Rebekah should have given me a horror novel, because my nickname for her is “Ghost Mouth.” (Thanks, Ghost Mouth!)

- THwaCiIW is a Gothic horror novel for kids, and it’s genuinely spooky. For one thing, it’s about a house with a goddamned clock in its walls! And not just any clock, but a doomsday clock that, when it goes off, will bring about the end of the world. The book’s protagonist, Lewis Barnavelt, along with his Uncle Jonathan, can hear the clock ticking all throughout their house, but they cannot find it. (The evil wizard who made and hid the clock cast a spell that causes the clock’s ticking to sound the same from inside every wall). And so neither the heroes nor the reader know when the clock will go off and cause the world to end. Which is like . . . Christ!

- The whole novel is tremendously suspenseful. Rereading it now, I still wanted to zip through to find out what would happen.

- I remember that, as a kid, the book scared the crap out of me. I found it frightening even now, reading it as an adult. I mean—it’s about a house with a goddamned doomsday clock hidden in its walls!

January 24th, 2013 / 9:53 pm

25 Points: Bright Lights, Big City / Model Behavior / Story of My Life

Bright Lights, Big City; Model Behavior; Story of My Life

Bright Lights, Big City; Model Behavior; Story of My Life

by Jay McInerney

Vintage, 1984; Vintage, 1998; Grove, 1988

buy from Powell’s

1. This winter I read/reread McInerney’s Bright Lights Big City and Model Behavior, and because of (sorry, Jay) certain undeniable narrative overlaps I decided to review them and Story of My Life together to shake loose some of the cocaine-infused cobwebs and move forward.

2. A. The first is written about a young man working at a highbrow New York magazine (McInerney himself worked for awhile at The New Yorker after being educated by such legends as Raymond Carver and Tobias Wolff at Syracuse) and is one of the first novels brought up when discussions of ‘2nd person narrative’ take place.

B. The second is a bit of a mess. Connor Mcknight is a journalist working at a NY magazine called Ciao Bella! that interviews starlets and although it features moments of hilarity or depth the book itself is marred by a stylistic indecision; perspective shifts (from 1st, to 2nd and 3rd person) abound and although it seems an interesting quirk it seems more likely that this ‘novel’ was crudely assembled by a halfway-decent craftsman of the drug story. I’m hard on it because I’ve believed in McInerney’s work while he’s been left in Bret Easton Ellis’s wake and his first book absolutely saves my life and reinvigorates my feelings for the personal narrative several times a year.

C. This book is a fucking work of art. Written in the perspective of a ditzy NYC twenty-something female named Allison Poole (a character based on Rielle Hunter, John Edward’s notorious lover and a recurring character in Bret Easton Ellis’s novels as well), it’s a distinct achievement regarding voice. Several of Carver’s stories are told in a female voice, and are difficult to believe even in a much shorter landscape, yet McInerney pulls off the lilts and preoccupations of a confused city girl with something like a magical control over language.

3. I once had a brief exchange with a person about my feelings toward The Strokes, to paraphrase: “They’re sort of a one-trick pony,” I said. “Yes, their one trick is being The Strokes, and they do it fucking well,” he replied; and although a part of me feels like taking a bite out of his cheek for a second even mentioning this again because I’m an idiot with issues, I feel it’s transferable to the aforementioned ‘overlaps’ throughout McInerney’s career and these books. He’s a New York writer, or at the very least an East Coast writer, and these are the sort of novels you pick up when you want to have fun, laugh a bit, and feel a slight inclination toward literary seriousness. They are good, they are fucking good, but something about them seems too damned similar to call one much better than the other without biographical considerations.

4. His first novel is obviously worthwhile and impressive because it’s his first book and was published in his twenties. It shows a sincere command not only over storytelling and plotting but also style and certain choices one can make in that realm of the ‘new literature’ then burgeoning in the states. I like the 2nd person here, which might be enough for most readers to decide it’s a decent book. 2nd person is difficult, you’re bound to come to the same tough decisions of identification with the characters and it’s because of the setting (NYC high society, drugs, literature, models, etc., yet also squalor) that McInerney’s ‘you,’ is so transferable. These are observatory environments, situations where you don’t necessarily need thick paragraphs a la John Irving or Stephen King to conjure up a scene in the typical sense; and when the protagonist finds himself (yourself) trapped in the calamity of the city as it was in the 80s the frenetic energy of ‘your’ story being told needn’t be hammered down your throat, which may lend itself to the shortness of both the chapters, and the novel itself.

5. As I said, Model Behavior is the least impressive. Like his Brat Pack fellow Ellis’s ‘The Informers,’ it strikes me as something probably assembled from youthful ramblings and attempts at literary savvy. The best parts of this book are those moments when 3rd and 2nd person fuck off for stretches and 1st person—a perspective that, I think, makes sense for your typical frantic ‘city/drug’ novel—is at the helm. Fans of this sort of minimalistic, energetic literature will absolutely enjoy what’s happening here, but don’t expect to be floored, and don’t use this as your gauge of McInerney’s potential because, frankly, as far as I can tell it’s his worst book.

6. Story of My Life is fucking funny, and the kind of fucking funny book that people who read and enjoy serious, even somber, literature can probably enjoy. It’s funny because the female voice is nearly flawless and imagining McInerney with his thick eyebrows and strict yuppie demeanor geeking out on this early on is simply refreshing. I’d call the voice something on the order of ‘valley girl’ and I think that’s accurate, however when I gave the book to my father to swap notes at one point he interpreted it more like Tony Soprano.

7. I took a shower later that night and laughed for a really long time about my dad’s mistake. Dads make mistakes a lot, I think, unless they’re not the sort of fathers you really perceive as fathers and then are they even dads?

8. No.

9. I’m going to now refer to Bright Lights Big City and Story of My Life as ‘the bread’ and Model Behavior as ‘whatever’ for convenience because for the most part I’m done insulting that book.

10. I like to get lost in the bread, they are the sorts of books that allow for that sort of thing. The first piece—his first book, Bright Lights—wraps you up like the first reading of Catcher in the Rye and lets all the angsty shit in your life fall by the wayside. READ MORE >

January 22nd, 2013 / 9:09 am

25 Points: Wittgenstein’s Mistress

Wittgenstein’s Mistress

Wittgenstein’s Mistress

by David Markson

Dalkey Archive Press, 1988

248 pages / $16.95 buy from Dalkey

1. David Markson published Wittgenstein’s Mistress in 1988, 37 years after the death of Ludwig Wittgenstein, whose name you may recognize from the novel’s title, or from his being an eminent 20th century philosopher.

2. How is it that one earns the designation philosopher, when one could just as accurately be called a philosophy professor (see also: Martin Heidegger, Immanuel Kant, et al.; technically Nietzsche taught philology)? It may have something to do with one’s work eventually being taught by other philosophy professors.

3. Or with someone someday writing a piece of experimental fiction indebted to one’s philosophy. Perhaps it helps if the title mentions one by name.

4. Possibly it is not unhelpful if one’s mentor is someone else people call philosopher (e.g., Bertrand Russell).

5. Ludwig Wittgenstein is not a character in Wittgenstein’s Mistress.

6. Maybe that’s not right. Possibly Ludwig Wittgenstein is a character in Wittgenstein’s Mistress. As are Rembrandt and Da Vinci and William Gaddis and Helen of Troy and a scratching cat that is in fact (“in fact”) only out of sight duct tape in the wind.

7. Unquestionably, a character in Wittgenstein’s Mistress is a woman named Kate, who had a son once, who is nearing menopause, who was once an artist, who knows a lot about art and art history and philosophy and literature, much of it, she claims, gleaned from footnotes. More questionably, Kate is the only person in the world.

8. Unquestionably, she believes herself to be.

9. One of the novel’s central conceits, if it is not too reductive to talk that way, is that whether or not Kate is “actually” alone in the world is pretty beside the point. Philosophers call this problem solipsism, while the rest of us call it loneliness.

10. The novel’s own text, in the context of the novel, is the artifact of Kate’s time (of course) alone at a typewriter. Ostensibly Kate’s aloneness makes the text necessarily therapeutic, rather than communicative, since there is no one in her world with whom she could communicate. Yet here the text is—in our world—as a novel, and here we are—the readers—reading, receiving it. READ MORE >

January 15th, 2013 / 12:05 pm

25 Points: Big Ray

Big Ray

Big Ray

by Michael Kimball

Bloomsbury USA, 2012

192 pages / $23.00 buy from Amazon

1. Big Ray blends genre between flash fiction and novel.

2. Each chapter within the work is told in first person confessional episodic moments, which read as a short flash fiction piece which could be read on its own as a complete story.

3. Each of the flash sections rarely surpass 200 words, though the sizes ebb and flow throughout.

4. Kimball heightens intensity by elongating the more anxiety-ridden sections of the book and in parallel compresses the sections which give appropriate if not beautifully told anecdotal backstory. In doing so, Kimball is showing his expertise as the mark of his incredible ability to craft story.

5. Michael Kimball is one of the nicest guys as a person in “the business.” Also, he can write. Dude can write.

6. Kimball is opening the reader to a complicated familial past quickly.

7. We are witness to Big Ray’s past and the way in which his ether has an everlasting effect on our narrator. As our narrator walks between Big Ray’s passing and their intertwined past as father and son Kimball provides us with generously rendered unfolding history, and in doing so, illuminates a thick, vastly layered novel which reads painfully, slowly, like ice melting in the most profound way possible.

8. “It makes him look as if he’s about to do some damage.”

9. Heartbreakingly, there is a kindness at work, a tongue in cheek commentary about the ways in which people, motivated by their own intentions, are terrible to one another, observe:

“Here’s what happened: After high school, my father went into the Marines and my mother went to college. My father lived in the barracks with dozens of other men and my mother moved into an apartment with a roommate who she didn’t know particularly well. To fill in the space between them, my mother and my father wrote letters to each other for months.

Then, without any explanation, my mother stopped receiving my father’s letters. Not long after that, my mother stopped writing letters to my father. Neither one of them knew what had happened. They both waited for months, thinking the other one had stopped writing.

What my mother didn’t know was that my father was still writing her letters. What my father didn’t know was that my mother wasn’t receiving the letters. This was because my mother’s roommate would come home to the apartment at lunch and steal my father’s letters.”

10. A part of the pain our narrator endures is a sense of trying to explain this narrative to himself. Which, is brilliant in that Kimball writes a guy who walks the line between reliable narrator and human being. He wants love, attention, appreciation, but imposed a sense of failure on himself, which leads to resentment and anguish again. What Kimball can do is paint, for any person, the pain felt in never really connecting with a parent, yet simultaneously connecting with a parent by default.

“My father’s life was an ordinary one in so many ways. I wonder if I am making him into something more than he was because he was my father.” READ MORE >

January 10th, 2013 / 12:04 pm

25 Points: Out of My Skin

Out of My Skin

Out of My Skin

by John Haskell

FSG, 2009

224 pages / $4.95 buy from Powell’s

1. Out of My Skin by John Haskell is about a man (named Haskell) who goes to Los Angeles and becomes interested in a Steve Martin impersonator. It’s about wanting to change who you are. It’s about identity and the loss of self in pursuit of some ideal.

2. The real Haskell was a journalist who moved to LA from NY. He wrote a collection of short stories called I Am Not Jackson Pollock. Over the course of nine stories, Haskell writes about movies and their actors. He confuses the actors with the roles they play because it symbolizes the confusion of outward expression and inward intention. There is a dichotomy of who the person is versus who the person wants to be or the role they are playing.

3. I started reading this book around the time the Mayan calendar was ending and the regular calendar was ending. There was some talk about change and transformation. I’ve always found New Years’ celebrations to be arbitrary. Why do people dedicate themselves anew at the beginning of the year, a random point in time? Why do people want to start over? And yet I am susceptible to it.

4. I shaved my head and my face. I wanted to be a different person. I was tired of my choices, decisions, life. What does it take to transform yourself?

5. This book is written in a way unlike any other book by any other author I have read or heard about. And I’m sure someone could say why or how it is different using literary criticism. But I didn’t read it in a litcrit way so my experience of it was maybe more pure. I liked it for what it was doing to me, how it made me experience reading in a totally new way, how it changed me.

6. One thing that is different about this book is that it is more focused on ideas than action. But the ideas are realized through specific events and objective narration. It is not pure theory. This story, the things that happened and the way it is told, makes you think about things, makes you observe them, the things in the book and in your life. It transcends the book, so that it changes you, affects you.

7. Every sentence is infused with meaning as if no one had ever thought of the way things correlated before, how everything fits together, the narrator keenly observing everything and trying to wring some kind of desperate meaning from normality. “I could feel the blades of grass pressing up through my shirt into the skin of my back.” This could be a description in any book, but because of what is happening in this book, it takes on an uncanny resonance.

8. Every time I go on a trip, I think change is possible when I return. I think I’ll become a different person or I believe I am a different person slipping into the disguise of who I used to be, but then that disguise, my real persona, wins out and takes over.

9. The character Haskell lets the Steve persona attain for him certain things he feels himself incapable of. But after a while he can no longer maintain the desire for the things that his Steve persona has attained. Being Steve has gotten in the way even though he is happy, or, he becomes less happy when he loses the things because he is no longer being Steve.

10. “By becoming Steve and then becoming not-Steve, I’d become a nonentity.” At first it seemed like this anonymity in LA would mean a loss of control, would make him too vulnerable, but it seemed to be what he actually wanted in the first place. Douglas Coupland writes in Life after God about how strange it is that you can never park your body and float free. But it seems like you can. There are drugs and alcohol which diddle your brain just enough to get you to feel a different way. You can also do it by projecting your mind. You can leave your body by reading a book. READ MORE >

January 8th, 2013 / 6:02 pm