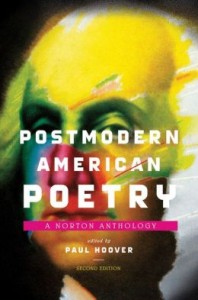

The Nation Versus The Norton Postmodern Anthology Disaster (2nd Edition)

RE: Postmodern American Poetry: A Norton Anthology (2nd Edition) / Edited by Paul Hoover / W.W. Norton & Co., March 2013

***

Anthologies serve a plainly economic purpose, if nothing else. Pedagogical too…most teachers and students of poetry—along with its general lovers everywhere—lack the time and/or wherewithal to go out and find so many individual titles on their own. This new Norton edition via Paul Hoover, generously upgraded since the first in 1994, writes Conceptual and Flarf poetry into a Postmodern American narrative that has become desperate for extensions. None of the poets here come off as desperate; the blanket labeling is merely academic. Once outside the classroom it feels very old-hat. But as poet and critic Ange Mlinko pointed out in her already notorious review of this book for The Nation, under what other aesthetic banner can a major publisher have the Zen nature verses of Gary Snyder together with K. Silem Mohammad’s rewritings of Shakespeare via an internet anagram generator?

It’s only been a couple of months since the anthology came out, and already there is a scandal in the works. Poets dig war. The politics/poetics of who gets left in, and who gets taken out, or who gets tacked on to the end remains an uninteresting mystery. Pop outliers like Charles Bukowski have been left out this time around, but the more high-profile writers of the Beat Generation, New York School 1st & 2nd generation(s), Black Mountain Poets and Language School are all given their due throughout these pages, once again. If you don’t know what any of those are, this book will no doubt be indispensable to you. Now the same goes for Conceptualism and Flarf. Flarf has never had its own private anthology (maybe on purpose?) while Conceptualism decidedly has, with Against Expression: An Anthology of Conceptual Writing just two years ago. Nevertheless, of all the poetry groupings/movements in this book, these two are still the most involved in the business of constantly redefining themselves before a potential public.

Experimental fiction as genre and as principle

A few years ago at Big Other I wrote a post entitled “Experimental Art as Genre and as Principle.” That distinction has been on my mind as of late, so I thought I’d revisit the argument. My basic argument then and now was that I see two different ways in which experimental art is commonly defined.

By principle I mean that the artist is committed to making art that’s different from what other artists are making—so much so that others often don’t even believe that it is art. As contemporary examples I’m fond of citing Tao Lin and Kenneth Goldsmith because I still hear people complaining that those two men aren’t real artists—that they’re somehow pulling a fast one on all their fans. (Someday I’ll explore this idea. How exactly does one perform a con via art? Perhaps it really is possible. Until then, I’ll propose that one indication of experimental art is that others disregard it as a hoax.) Tao visited my school one month ago, and after his presentation some folks there expressed concern, their brows deeply furrowed, that he was a Legitimate Artist—so this does still happen. (For evidence of Goldsmith’s supposed fakery, keep reading.)

Eventually, I bet, the doubts regarding Lin and Goldsmith will fall by the wayside. Things change. And it’s precisely because things change that the principle of experimentation must keep moving. The avant-garde, if there is one, must stay avant.

That’s only one way of looking at it, however. Experimental art becomes genre when particular experimental techniques become canonical and widely disseminated and practiced. The experimental filmmaker Stan Brakhage, during the 1960s, affixed blades of grass and moth wings to film emulsion, and scratched the emulsion, and painted on it, then printed and projected the results. Here is one example and here is another example. And here is a third; his films are beautiful and I love them. (The image atop left hails from Mothlight.) Today, countless film students also love Brakhage’s work, and use the methods he popularized to make projects that they send off to experimental film festivals. (Or at least they did this during the 90s, when I attended such festivals; I may be out of touch.)

Those films, I’d argue, while potentially beautiful and interesting, are not necessarily experimental films. As far as the principle of experimentation goes, those students had might as well be imitating Hitchcock.