In case you missed it, this piece in the Boston Review today is causing quite a stir on the interwebs: Against Conceptualism: Defending the Poetry of Affect. Bringing it into this sphere. Curious to hear thoughts from readers?

The difference between a concept & a constraint, part 2: What is a constraint?

OK, back to this. In Part 1, I traced out how in conceptual art, the concept lies outside whatever artwork is produced—how, strictly speaking, the concept itself is the artwork, and whatever thingamabob the artist then uses the concept to go on to make (if anything) counts more as a record or a product of the originating concept. (This is according to the teachings of Sol LeWitt, as practiced by Kenneth Goldsmith.) Thus, we arrived at the following formulation:

- Artist > Concept > Artwork (Record)

Now, I’m not going to argue that every conceptual artist on Planet Earth works according to this model. But LeWitt’s prescription has proven influential, and continues to be revolutionary—because choosing to work with either a concept or a constraint will lead an artist down one of two very different paths. To see how this is the case, let’s try defining what a constraint is, aided by the Puzzle Master himself, Georges Perec . . .

The difference between a concept & a constraint, part 1: What is a concept?

Sol LeWitt: “Wall Drawing #1111: A Circle with Broken Bands of Color” (2003, detail). Photo by Jason Stec.

[Update: Part 2 is here.]

I wrote about this to some extent here, but I wanted to expound on the issue in what I hope is a more coherent form. Because I frequently see concepts confused with constraints, and the Oulipo lumped in with conceptual writing. For instance, this entry at Poets.org, “A Brief Guide to Conceptual Poetry,” states:

One direct predecessor of contemporary conceptual writing is Oulipo (l’Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle), a writers’ group interested in experimenting with different forms of literary constraint, represented by writers like Italo Calvino, Georges Perec, and Raymound Queneau. One example of an Oulipean constraint is the N + 7 procedure, in which each word in an original text is replaced with the word which appears seven entries below it in a dictionary. Other key influences cited include John Cage’s and Jackson Mac Low’s chance operations, as well as the Brazilian concrete poetry movement.

I would argue that the Oulipo, historically speaking, are not conceptual writers/artists—although it’s easy to see how that confusion has come about, because the Oulipians have proposed some conceptual techniques, such as N+7 (which I’d argue is not a constraint). (Also, it’s each noun that gets replaced, not each word.)

What, then, distinguishes concepts from constraints? And why does that distinction matter? In this series of posts, I’ll try answering those questions, starting with what we mean when we call art conceptual.

What we talk about when we talk about the New Sincerity, part 2

"Hi, How Are You?" cover art by Daniel Johnston (1983); "financially desperate tree doing a 'quadruple kickflip' off a cliff into a 5000+ foot gorge to retain its nike, fritos, and redbull sponsorships " by Tao Lin (2010)

It made me very happy to read the various responses to Part 1, posted last Monday. Today I want to continue this brief digression into asking what, if anything, the New Sincerity was, as well as what, if anything, it currently is. (Next Monday I’ll return to reading Viktor Shklovsky’s Theory of Prose and applying it to contemporary writing.)

Last time I talked about 2005–8, but what was the New Sincerity before Massey/Robinson/Mister? (And does that matter?) Others have pointed out that something much like the movement can be traced back to David Foster Wallace’s 1993 Review of Contemporary Fiction essay “E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction” (here’s a PDF copy). I can recall conversations, 2000–3, with classmates at ISU (where DFW taught and a number of us worked for RCF/Dalkey) about “the death of irony” and “the death of Postmodernism” and a possible “return to sincerity.” Today, even the Wikipedia article on the NS also makes that connection:

Viktor Shklovsky wants to make you a better writer, part 1: device & defamiliarization

When I was finishing up my Master’s degree at ISU, I worried that I still didn’t know much about writing—like, how to actually do it. My mentor Curtis White told me, “Just read Viktor Shklovsky; it’s all in there.” So I moved to Thailand and spent the next two years poring over Theory of Prose. When I returned to the US in the summer of 2005, I sat down and started really writing.

I’ve already put up one post about what, specifically I learned from Theory of Prose, but it occurs to me now that I can be even more specific. So this will be the first in a series of posts in which I try to boil ToP down into a kind of “notes on craft,” as well as reiterate some of the more theoretical arguments that I’ve been making both here and at Big Other over the past 2+ years. Of course if this interests you, then I most fervently recommend that you actually read the Shklovsky—and not just ToP but his other critical texts as well as his fiction, which is marvelous. (Indeed, Curt has since told me that he didn’t mean for me to focus so much on ToP! But I still find it extraordinarily useful.)

Let’s talk first about where Viktor Shklovsky himself started: the concepts of device and defamiliarization.

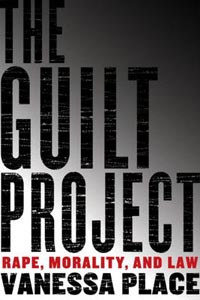

On The Guilt Project: Rape Morality and Law & Tragodía 1: Statement of Facts by Vanessa Place

The Guilt Project

The Guilt Project

by Vanessa Place

Other Press, 2010

336 pages / $25 Buy from Amazon

&

Tragodía 1: Statement of Facts

by Vanessa Place

Blanc Press, 2010

430 pages / $45 (HB), $25 (PB) Buy from Blanc Press

Among the individuals in Los Angeles who are responding to heavyweight issues exists an uncanny force: Vanessa Place. A criminal defense attorney, she defends what some categorize as the lost, the wretched: indigent criminals, repeat sex offenders and violent predators. Some criminals learn valuable lessons while incarcerated; others leave prison refueled, angry and ready to re-enter what’s left of the world as a less worthy version of themselves, less interested in following pre-ordained rules. This is where Place steps in: the blurry space between offense and re-offense, perpetrator and victim, right and wrong, ethics and morality. Place explains, “I work as a combination street sweeper and factory worker. I follow what’s gone before, mopping up after the bloody mess, squaring the legal corners, assembling the lives disassembled by tragedy, and reducing reams of paper to bite-sized pellets.”(p.2)

August 8th, 2011 / 12:00 pm