Craft Notes

Theory of Prose & better writing (ctd): The New Sincerity, Tao Lin, & “differential perceptions”

In the first post in this series, I outlined Viktor Shklovsky’s fundamental concepts of device (priem) and defamiliarization (ostranenie) as presented in the first chapter of Theory of Prose, “Art as Device.” This time around, I’d like to look at the start of Chapter 2 and try applying it to contemporary writing (specifically to the New Sincerity). As before, I’m proposing that one can actually use the principles of Russian Formalism to become a better writer and a better critic.

Chapter 2 is titled “The Relationship between Devices of Plot Construction and General Devices of Style,” and it covers a lot of ground. Shklovsky begins by asking why certain plots and motifs can be observed throughout literature, even when that literature is vastly separated by time and space. He dismisses the idea that the plots and motifs are being passed along, and proposes instead that they are being independently invented or (re-)discovered time and again. By his reasoning, since literature is made up of devices—that’s all that literature is—there are patterns that govern the ways in which those devices get put together, and people keep exploring those patterns. As he puts it:

The story disintegrates and is rebuilt anew. […] Coincidences can be explained only by the existence of special laws of plot formation. (17)

From there, he sets out to describe those special laws.

But first Shklovsky circles back, providing a fuller account of defamiliarization in light of this new proposal. There are two points to take in here.

1. Context

Shklovsky first notes that artists are necessarily always working in relation to one another, and to history:

I would like to add the following as a general rule: a work of art is perceived against a background of and by association with other works of art. The form of a work of art is determined by its relationship with other preexisting forms. The content of a work of art is invariably manipulated, it is isolated, “silenced.” All works of art, and not only parodies, are created either as a parallel or an antithesis to some model. The new form makes an appearance not to express a new content, but rather, to replace an old form that has already outlived its artistic usefulness. (20, emphasis in the original)

This is a very dense quote, so let’s take it one step at a time. First, what counts as defamiliarization is contingent on time and place—on whatever devices and patterns of devices count as familiar.

Let’s try out this thought on an example from contemporary letters: the New Sincerity. Very briefly and very broadly, the NS started as a half-silly, half-serious movement launched c. 2004 by Joseph Massey, Andrew Mister, and Anthony Robinson. They wrote manifestos and blogged a lot and called for a poetic return to earnest self-expression and sincerity. Other writers since have either fairly or unfairly come to be identified with this philosophy and style: Dorothea Lasky, Matt Hart, Nate Pritts, Tao Lin and the Muumuu House scene, Marie Calloway, Steve Roggenbuck—and many others.

I have a lot to say about the New Sincerity, and intend to discuss it at length in future posts and articles both here and elsewhere. But for now, permit me to stick with this oversimplification. (I think we can agree that the writers I’ve just mentioned, despite their palpable differences, all share at least something or things in common, stylistically—as opposed to, say, Vanessa Place, or Joshua Cohen, or Dodie Bellamy, or Jonathan Franzen.)

If I’m right, and if Shklovsky is right, then what gives the New Sincerity its overarching identity is the fact that a (loose-knit) group of writers are using some number of shared devices and patterns of devices. Me, I think that’s absolutely right. With apologies to Elisa Gabbert and Mike Young, here are some of the New Sincerity’s moves:

- Lots of autobiography (lots of lines starting with “I”), which is itself often confessional. (Certain subjects, such as one’s emotions and actual life experiences, are considered “more appropriate” or “better” content.) Sometimes this autobiography is masked (Richard Yates, Marie Calloway), but only thinly.

- Apostrophe (in the poetry).

- Minimal punctuation.

- In the poetry, stanza and line lengths are often irregular.

- Long, rambly lines or steady paragraphs of even, neutral lines. Note that the purpose here, and in 3 and 4, is to create the sense that the work is artless (i.e., neither artificial nor contrived).

- Self-revision; fumbling about for words (Lasky: “I think poems come from the earth and work through the mind from the ground up. I think poems are living things that grow from the earth into the brain, rather than things that are planted within the earth by the brain. I think a poet intuits a poem and a scientist conducts a ‘project.’ I don’t know. That seems wrong, too.”) (See also Lin’s maximal use of scare quotes.)

- Similar to 6: A tendency toward conversational/discursive tones. (Note that this is still a matter of rhetoric!) This gets at a shared fondness for Facebook/Twitter/Google Chat/etc., which are essentially endless conversations.

- A professed hatred of irony and overt cleverness. (“Enemies” here include Language Poetry, Conceptual Poetry, and “formulaic” MFA lyricism that “deadens” language.) (See also Tao Lin’s current “Not Trying” period.)

- Favorite subjects: childishness, mental illness, emotion and the lack thereof, as well as the sudden upswell of uncontrollable emotion (anything that evades governing consciousness).

- A fondness of sans-serif fonts / ampersands / text-speak (all of which “feel more contemporary” or “more spontaneous”—less traditionally literary.

N.B. This is far from a definitive list, and I’m not arguing that every New Sincerist work will employ every one of these devices. Nor am I trying to say that all of the writers mentioned above are all doing “the same thing.” I’m just sketching out a general style that has been increasingly observable in poetry and then fiction between 2004 and the present (as opposed to Language Poetry, Conceptual Poetry, MFA lyricism/realism, others).

Overall, the goal of the NS style seems to be to write poetry and prose that produces the effect of somehow being sincere/real/transparent/artless, and less theoretical/abstract/mediated/artificial. (For more along these lines, see Jennifer Moore’s recent article in Jacket2, “‘Something that stutters sincerely’: Contemporary poetry and the aesthetics of failure.“)

Now let’s look more closely at Tao Lin. Certainly his work is popular. There’s also been a lot of ink spilled over the past six years or so as to whether his work is “legitimate,” vs. some kind of put-on or hoax. “He’s just transcribing G-chat conversations” is an oft-heard criticism (I know I’ve often heard it), and the implication of that criticism is that Lin’s work is artless and easy. For two examples, see reviews of Richard Yates by J. A. Tyler (at Big Other) and Joshua Cohen (in Bookforum), both of which effectively accuse the work of being artless and therefore not worth taking seriously as literature. Here’s how Josh put it:

Total transparency will always resolve itself in reduced expression (short paragraphs, “sentagraphs,” short sentences), as subjects like boredom become objectified in prose. Instead of encountering the syntactically strange, or a project of genuine depersonalization or fracture, Lin’s readers are stroked by a continuous stream of neutral declaratives. If Lin retains this transparency there will literally be no other way he can write; his style, once electively autistic, will become a disability, the dictator of his thoughts (it would be impressive if Lin went all Fernando Pessoa on us and wrote heteronymously). Literature is made when a writer exploits different rhetoric in an attempt to manipulate a reader; Lin’s “literature” is the account of his manipulation of his girlfriend in a prose that is interchangeable with anything online written by the under thirty commentariat.

I would argue that Josh is making several crucial mistakes:

1. His first sentence doesn’t follow logically. What the New Sincerists wonder, ultimately, is “what devices in the here and now give the impression of transparency, of artlessness, of pure unmediated sincerity?” Those devices need not be what Josh claims they are. Indeed, many NS writers use long sentences and long paragraphs. But Josh repeats this mistake throughout the paragraph. (“If Lin retains this transparency there will literally be no other way he can write.”)

I wrote in Part 1 that there are no experimental devices, just experimentation with devices. Similarly, there are no devices that eternally “feel sincere,” and no writing that will always count as sincere. What feels visceral and non-contrived at any given moment will always be measured against whatever currently feels bloodless and contrive, and this is always in flux. (Familiarization is always at work on literature.)

2. Josh claims that “a continuous stream of neutral declaratives” can’t be “syntactically strange, or a project of genuine depersonalization or fracture.” In other words, he’s claiming that such writing (Lin’s in particular) lacks the power to defamiliarize. Here he’s making the same mistake that Chris Higgs does: claiming that certain devices can/can’t be used to produce defamiliarization. I hope that my arguments here and in Part 1 sufficiently demonstrate why I think this is completely, utterly wrong.

Language Poetry, for instance, often consists of “a continuous stream of neutral declaratives”— see e.g. Lyn Hejinian’s My Life (1980/87):

You spill the sugar when you lift the spoon. My father had filled an old apothecary jar with what he called “sea glass,” bits of old bottles rounded and textured by the sea, so abundant on beaches. There is no solitude. It buries itself in veracity. It is as if one splashed in the water lost by one’s tears. My mother had climbed into the garbage can in order to stamp down the accumulated trash, but the can was knocked off balance, and when she fell she broke her arm. She could only give a little shrug. The family had little money but plenty of food. At the circus only the elephants were greater than anything I could have imagined. The egg of Columbus, landscape and grammar. She wanted one where the playground was dirt, with grass, shaded by a tree, from which would hang a rubber tire as a swing, and when she found it she sent me. These creatures are compound and nothing they do should surprise us. I don’t mind, or I won’t mind, where the verb “to care” might multiply. The pilot of the little airplane had forgotten to notify the airport of his approach, so that when the lights of the plane in the night were first spotted, the air raid sirens went off, and the entire city on that coast went dark. He was taking a drink of water and the light was growing dim.

And here’s the start of the opening paragraph/chapter of Yuriy Tarnawsky’s Three Blondes and Death (FC2, 1993):

It was in the middle of May. It was unusually warm however. As a consequence it felt like the middle of June. It was a Sunday. Hwbrgdtse was with a friend. The friend was a man. His name was Valentin. Hwbrgdtse and Valentin were going to horse races. The races were held out in the country. The racetrack was far away from the city. Going to the races therefore Hwbrgdtse and Valentin saw a lot of the countryside. It’d been unusually warm all of that spring. The vegetation was much more advanced than usual. It really looked almost as in the middle of June. The grass was thick. It was bright green. It covered the earth like a thick layer of paint. The paint looked shiny. It seemed still wet. It seemed to have been poured out of a can and to have spread over the earth. It seemed to have spread by itself. The earth therefore seemed tilted. (13)

There is always some normative way or ways of employing a device, and as such there are always a non-normative way to defamiliarize it (especially when those devices start getting assembled into patterns and forms).

(My ultimate argument has always been with anyone who would claim that writing need be done a certain way.)

3. What’s more, I’d argue that Lin’s writing is plenty defamiliarizing—hence the very tendency of reviewers to refuse to take it seriously as literature! I myself would argue that Lin’s a fairly experimental novelist, because in Shoplifting and Richard Yates he so defamiliarizes so many devices—he deforms the works so thoroughly—that many have had trouble accepting them as novels.

(Experimental writing and realism are not opposites! Some devices and patterns, in a given time and place, will read as having a more “realistic” effect than others, but all is still artifice. Meanwhile, one can experiment with any device, any pattern.)

4. While it’s somewhat unclear what Josh means by “different rhetoric,” I think he’s basically arguing that Lin’s style—Lin’s devices—don’t count as literature. That’s nonsense. As unfamiliar as Shoplifting and Richard Yates may look, they’re also demonstrably novels. Richard Yates even announces itself as partaking in an established literary tradition: the suburban realist novel, a la Richard Yates’s own Revolutionary Road (1961).

Miserable couples will be with us always. The suburbs, God help us, may also be with us always. So the pertinent question is: How does an author in 2010 describe the miserableness of those suburban couples in a way that feels contemporary and real? Many of the devices and strategies that Richard Yates the man used fifty years ago no longer help; they have become too familiar. (They don’t feel stony.)

And so Richard Yates the novel must use different ones. Lin’s success in this comprises a large part of his novel’s brilliance.

5. If Lin’s writing is similar to other writing out there (“anything online”), then that is the result of shared conventions—the employment of similar devices. But Josh goes too far when he claims that Richard Yates is “interchangeable” with such. Lin, rather, is crafting his prose in Richard Yates to give the impression that it is like online prose—that it is contemporary, unmediated, and sincere. But that’s a rhetorical effect—and the novel is more than just that. (You can see this even in the examples that Josh has cherry-picked.)

In summary, Josh mistakes Lin’s writing for “transparency,” and therefore something artless. What he’s missing is that this seeming transparency and artlessness is entirely the product of rhetoric—of devices.

… Where does this lengthy tangent get us in terms of Shklovsky? Or where does Shklovsky get us in terms of all of this? Quite simply, Tao Lin provides us with a very useful example of that paragraph I quoted above:

I would like to add the following as a general rule: a work of art is perceived against a background of and by association with other works of art. The form of a work of art is determined by its relationship with other preexisting forms. The content of a work of art is invariably manipulated, it is isolated, “silenced.” All works of art, and not only parodies, are created either as a parallel or an antithesis to some model. The new form makes an appearance not to express a new content, but rather, to replace an old form that has already outlived its artistic usefulness. (20, emphases in the original)

I hope it’s clear by now why I think the New Sincerity is a response to preexisting literature (because it, uh, is!). But what in turn has transpired since 2004?

When Lin and other New Sincerists began writing the way that they did, the work “felt sincere”—it often felt so transparent and unmediated and unaffected that many have failed to see the devices at work.

But such writing has also become increasingly commonplace. Due to the New Sincerity’s popularity—and especially due to Lin’s publishing success—a lot of people, especially younger writers, are busy imitating him. (Mind you, I hardly think this is a bad thing; imitation is how and where we all begin.) This newly sincerely stony realist style is right this second becoming codified and familiarized. Later writers who want to make use of it—those who want to produce texts that still feel sincere, unmediated, transparent, rock solid—will need to find new variations on these current forms, and eventually find new forms, and new devices.

In twenty more years, Lin’s writing, as well as most New Sincerist writing, will look just as mannered and artificial as the minimalist realists of the 1970s and 80s—Raymond Carver, Ann Beattie, Amy Hempel, Joy Williams—do to you and me.

2. “Differential Perceptions”

This post has already claimed much I think others might find contentious. (It will be my pleasure to discuss any of this further in the comments section / subsequent posts.) But before I sign off, I’d like to discuss the other point Shklovsky makes about defamiliarization’s contextual aspect. To this end he quotes a long passage from Broder Christiansen (misspelled as V. Khristiansen) regarding “differential perceptions” (20–2). This is a dense little section well worth lingering over, though I’ll try being brief. Consider this excerpt (from Christiansen):

Why is the lyrical poetry of a foreign country never revealed to us in its fullness even when we have learned its language?

We hear the play of its harmonics. We apprehend the succession of rhymes and feel the rhythm. We understand the meaning of the words and are in command of the imagery, the figures of speech and the content. We may have a graps of all the sensuous forms, of all the objects. So what’s missing? The answer is: differential perceptions. The slightest aberrations from the norm in the choice of expressions, in the combination of words, in the subtle shift of syntax—all this can be mastered only by someone who lives among the natural elements of his language, by someone who, thanks to his conscious awareness of the norm, is immediately struck, or rather, irritated by any deviation from it. (21)

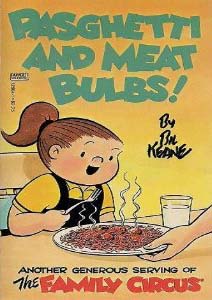

Here succinctly summarized is what we find so endearing about the speech of children and non-native speakers. Whole bodies of work—those of Bill Keane and the folks behind Engrish.com, to name but two—are rooted entirely in such perception:

The phenomenon known as Outsider Art also takes this principle to heart (and into the gallery).

Now it must be noted that differential perception is not synonymous with defamiliarization. Rather, defamiliarization is the artistic application of this principle. The artist manipulates a familiar aspect of the work (a device) such that it is perceived differently—and thus perceived. We see precisely this progression (differential perception -> defamiliarization) in the Oulipo’s famed n+7 technique:

- The cat wants to jump up on the table.

- The catastrophe wants to jump up on the taboo.

… and in many other places as well, such as the Oulipo-inspired technique I wrote about last week, “dictionary expansions.”

Note also that it takes only a minor alteration to render an otherwise banal sentence odd:

- The cat wants to jump up on the table.

- The cat wants to jump up to the table.

The writing of bizarre language, and the production of defamiliarization in general, need not be anything strenuous.

There’s so much more we could observe here—for instance, why advertisers and companies so frequently misspell words (to stand out, duh), and why expressions like “I’m lovin’ it” can become catchphrases (“to love” is a stative verb and as such doesn’t normally form the progressive). But let’s instead wrap up. What matters is how a piece of writing is perceived against the norm; that norm simultaneously being internal (the devices and patterns the work employs) and external (the background context provided by other works).

This post has now run far too long, and there’s still a great deal in Chapter 2 to talk about—namely the specific rules of plot formation Shklovsky identifies. I’ll pick up there next time. Until then—

—just you try being sincere.

See also:

- Viktor Shklovsky wants to make you a better writer, part 1: device & defamiliarization

- Another way to generate text #1: “The Spell Check Technique”

- Another way to generate text #2: “backmasking”

- Another way to generate text #3: “dictionary expansions”

Tags: Bill Keane, Broder Christiansen, Christopher Higgs, dictionary expansion, dorothea lasky, Douglas Robinson, elisa gabbert, engrish, Family Circle, J. A. Tyler, Joshua Cohen, Language Poetry, Lyn Hejinian, Marie Calloway, Matt Hart, Mike Young, muumuu house, n+7, narrative, nate pritts, New Sincerity, oulipo, plot, Revolutionary Road, richard yates, Russian Formalism, steve roggenbuck, Tao Lin, Viktor Shklovsky, Yuriy Tarnawsky

I agree that experimental writing (whatever that is) and realism (whatever that is) are not opposites. Mainly because they can’t be defined fully-one person’s realism is another’s experiment. Or to ask for an echo from a master:

“There can be no poetry without

the personality of the poet, and that, quite simply, is why the definition of

poetry has not been found and why, in short, there is none”? – The Figure of the Youth as Virile Poet (essay)

This: “In twenty more years, Lin’s writing, as well as most New Sincerist

writing, will look just as mannered and artificial as the minimalist

realists of the 1970s and 80s—Raymond Carver, Ann Beattie, Amy Hempel,

Joy Williams—do to you and me.”

is curious to me because one can argue everyone gets mannered. But to hopefully destroy any argumentation, a person wanting an experience of art might not care if it’s mannered or not. Ask a non-writer (or someone not vested in critically shearing the woolies off the experience of art) why they like Carver. I’ll bet they’ll talk about the down to earth characters, etc. But I think they will also say it makes them feel something.

But truly I responded to this last week: http://bigother.com/2012/05/24/critical/

I agree with this but I do think that Joshua Cohen’s following criticism was valid:

If Lin retains this transparency there will literally be no other way he can write; his style, once electively autistic, will become a disability, the dictator of his thoughts (it would be impressive if Lin went all Fernando Pessoa on us and wrote heteronymously).

All of Tao Lin’s writing appears profoundly anti-intellectual with the complete lack of ability to construct a voice that deviates from his autistic monotone. The plethora of Tao Lin imitators are not mimicking any kind of qualities that could be considered the brandishing of a New Sincerity movement, but rather they are imitating his freshmen level lexicon and utter lack of diversity.

It reminds me of an interview with zachery german that I read in which the interviewer asked zachery to write the same paragraph using a different kind of prose style in which he replied:

Zachary is wearing a blue jacket. He is in a Chinese restaurant. Zachary looks at Tao. He looks at Jamie. Zachary says “I’m going to the bathroom.” Zachary walks down stairs. He walks into a bathroom. He locks the door. Zachary looks at himself in the mirror. He thinks “Fuck.” Zachary looks at himself in the mirror. He opens his mouth. He closes his mouth. There is a can of Sparks malt beverage in Zachary’s jacket pocket. He picks up the can of Sparks malt beverage. He opens it. Zachary drinks from the can of Sparks malt beverage. He picks up his cell phone. Zachary looks at his cell phone. He takes a picture of himself with his cell phone, in the mirror. He puts his cell phone into his pocket. He finishes drinking the Sparks malt beverage. He puts the can of Sparks malt beverage into a trash can. He pees. He washes his hands. Zachary washes his face. He picks up a paper towel. He rubs the paper towel against his face. Zachary puts the paper towel into the trash can. He picks up a paper towel. He rubs the paper towel against his face. He puts the paper towel into the trash can. Zachary looks at himself in the mirror. He thinks “Fuck.” He opens the door. He walks out of the bathroom. He walks up stairs. He sits down.

As the first style of prose and:

Chinese restaurant. Blue jacket. Says something. Walking. White people, Chinese people. Sees a Mexican. Knocks on a door, knocks again, opens the door. Locks the door, opens a can of Sparks. Thinks about what’s happening, his girlfriend, thinks about his friend. The event he was at earlier, his novel, publisher. He has some Sparks in his jacket, takes it out, opens it, drinks it. Looks at his cell phone, takes a picture of himself in the mirror. Looks at his cell phone. Thinks about the internet. Puts his phone in his pocket, the Sparks in the trash. Pees, spits in the sink. Washes his face, hands. Thinks some more, looks at himself in the mirror. Remembers high school, rubs a paper towel against his face, another paper towel against his face. His face is dry. Opens the door, two people are waiting, walks upstairs, sits down.

As the second. It’s as if this minimalist style of writing isn’t a conscious rebuttal to post-modernism but really is the best that some of these writers can put forth and any effort to write in a different style results in them writing a bunch of incoherent phrases. It really would be refreshing to see someone from the muumuu house scene put forth a complex analytically work…just to see if they are capable of such writing.

It would be like Picasso being unable to paint in any sort of fashion besides cubism.

Other parts of this post I agree with, and I happen to be a fan of Tao Lin’s…just wanted to address that one point.

I don’t think the NS are “(‘Enemies’ [of] Language Poetry, Conceptual Poetry . . .)” because they are both about engaging in writing/reading in a way that feels alive — if you can get into it/get it.

Still reading through your post though, so may be wrong on that assumption.

Provisional painting and the new casualists,

http://www.artinamericamagazine.com/features/provisional-painting-raphael-rubinstein/

http://brooklynrail.org/2011/06/artseen/abstract-painting-the-new-casualists

“works that look casual, dashed-off, tentative, unfinished or self-cancelling.”

You’re generous, Adam. You know that moment in workshop (or, fuck, ANY English course) where someone tries to analyze a story and gives it this really smart and savvy reading but you and everyone else knows it’s totally wrong because the author didn’t have that intention – and words do betray intention, sure, as in looking at the words as they are on the page – and the student is giving her way too much credit? At some point, someone ought to intercede and say: Hey, I think your reading of this story is really smart, but honestly, sometimes, a rose is a rose, a spade is a spade, this is this, that is that, and transparency is exactly that and nothing more. And the student is trying to say: No way, in THIS case, a rose is a spade, this is that, and transparency is solid. Yeah well, ok, sure.

Shklovskian rediscoveries: the Platonism of submergence and re-emergence http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/gadamer/#HapTra , the Aristotelianism of mimetic desire concretized http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rene_Girard#Mimetic_desire .

“Twenty years”? Through the mystery of celebrity, Tao Lin’s style has become ‘normal’ already, somewhat, hasn’t it? I mean that that particular recognition of style generates the antagonism to what haters think of as ‘Tao Lin the Not-so-new Insincerist’.

I wonder to what extent Tao Lin’s defamiliarity – and to me, his style is weird: sometimes-pleasingly awkwardly not (or poorly) ‘literary’ – is due to its vessel or packaging as “literary”. The Tao Lin Derangement Syndrome – the shrilly anxious denunciations – — are they not protections of “literature”? which are themselves, as you suggest, evidence of “literature”?

That “autistic monotone” = a style.

Tao Lin does actually use a variety of styles. See the stories in “Bed.” Or compare his novels and his blog posts.

Your confidence that that second passage of ZG’s is self-evidently “a bunch of incoherent phrases” is poorly judged.

“‘He’s just transcribing G-chat conversations’ is an oft-heard criticism”

When I see things like that I sometimes think of how when Picasso incorporated cigar bands into his paintings and Toulouse-Lautrec painted in the style of cabaret posters, people were like, “Those things aren’t art.”

I tend to agree with Alan. I’ve read all of Lin’s books, and find them all to be pretty stylistically varied. Richard Yates and Shoplifting are pretty different. And Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and you are a little bit happier than i am are different from that, and different from one another, too. It has seemed to me for a while now that Lin’s thoroughly exploring variations within a few set constraints—something that critics and audiences usually profess to like.

“If Beckett retains this transparency there will literally be no other

way he can write; his style, once electively autistic, will become a

disability, the dictator of his thoughts […]”

“If Markson retains this transparency there will literally be no other

way he can write; his style, once electively autistic, will become a

disability, the dictator of his thoughts […]”

“If Hemingway retains this transparency there will literally be no other

way he can write; his style, once electively autistic, will become a

disability, the dictator of his thoughts […]”

Etc.

I agree but a lot of people perceive them that way (hence my quotes). The original NS gang, Massey/Mister/Robinson, were quite vocal in their dislike of Language Poetry and the MA scene. And Lasky’s pamphlet is clearly some kind of attack on, or criticism of, conceptual writing (although I think that book’s much more complicated than that; I just wrote an analysis of it at school).

I do know that moment and I do like being called generous! But I don’t think I’m attributing anything other to Lin than what he has done, if that’s what you’re implying :)

Yeah, I see a lot of the style right now. But I also just tend to see style. I said 20 because I think that’s a safe bet for when it’s painfully obvious.

The other thing I see in Lin’s work is that it is constantly indebted to other literature. He is plainly working within certain clear traditions and, I think, doing a brilliant job of finding new life in them. It doesn’t make much sense to me to not call him literary, although I understand, I think, why others might say that about him.

Yeah. I’ve never quite understood that criticism. Shoplifting and Richard Yates include G-chat conversations but they’re narrated; they aren’t just copy and pasted into the books. Lin is working with those materials, which strike me as materials many authors should want to work with—they are the things of our present moment!

But people can be myopic that way. They can think it’s OK for John Cage to have used tape recorders and the I Ching, but not OK for, say, Steve Roggenbuck to use Twitter or Tumblr.

I also don’t think Lin’s writing appears profoundly anti-intellectual. Rather, he strikes me time and again in print as a total intellectual. The work is, I’d argue, extremely thought out. That’s what mannerism often is: a very thought out and exaggerated style.

Yuriy Tarnawsky’s Three Blondes and Death was never as widely as read as Lin’s writing is, though it should have been. But it seems to often provoke people the same way:

http://www.librarything.com/work/2234550/reviews/

That Elkins review is a smarter version of what Josh wrote, though it’s still wrong (and more carefully worded, since Elkins is more actually concerned with critical evaluation than I suspect Josh was in his piece).

hey man, it’s 2012, writers aren’t pseudonymous or heteronymous, there’s a whole spectrum in between

Also, for anyone keeping track at home, Tarkawsky’s Three Blondes and Death is my “other favorite novel of the past 25 years” (along with Markson’s Wittgenstein’s Mistress). It’s a real shame more people haven’t read it.

But then poor everyone.

Also, for anyone keeping track at home, Tarkawsky’s Three Blondes and Death is my “other favorite novel of the past 25 years” (along with Markson’s Wittgenstein’s Mistress). It’s a real shame more people haven’t read it.

But then poor everyone.

oops

‘All of Tao Lin’s writing appears profoundly anti-intellectual with the complete lack of ability to construct a voice that deviates from his autistic monotone.’

http://eeeee-eee-eeee-bed.blogspot.com/2006/08/though-shed-begun-to-get-bit-fat-that.html

http://thoughtcatalog.com/2011/koko-the-talking-gorilla/

http://www.vice.com/read/drug-related-photoshop-art-tao-lin-retrospective-at-the-whitney

http://www.vice.com/read/relationship-story-v18n6

http://thoughtcatalog.com/2011/almost-transparent-blue-ryu-murakami/

Have you read any of these?

Is it relevant that the author in question was traumatized as a toddler when he was bitten by a conjunction?

Yikes, that Elkins review. I hate it when people are like, “I’m not a philistine, I admire Beckett, Stein, and the Oulipo writers for using those devices, but they knew what they were doing, unlike [contemporary writer X].”

sweet

James Elkins is a very smart man and an excellent teacher and writer—I rather admire his book Why Art Cannot Be Taught—but, yeah, that review.

http://www.press.uillinois.edu/books/catalog/93dtx3tx9780252069505.html

[…] promised, the second installment of AD Jameson’s provocative commentary on Viktor Shklovsky and the devices operating in […]

This keeps coming up everywhere so let’s do this: let’s go easy on throwing around autism as a style or nature or device; it’s pretty spectacularly dumb. I’m autistic, and flatness, navel-gazing and banality are not synonymous with autism at all. Sorry. We’re actually pretty fucking lively, and our writing, online or in print, is indistinguishable from your writing, except maybe that none of us are probably Newly Sincere because we know you can never get away from the inherent artifice of any language event, whether it’s a novel or a twitter post or whatever, so you need to reckon with that artifice instead of shunning it or pretending to ignore it, because you ultimately don’t have a choice.

nice Adam. rhetorically logical, coherently/appealingly-written, imo

Bookforum, who published Cohen’s hatchet job, also recently linked to an extremely positive essay on Tao in a manner that buried the lede completely, making it sound like the piece was about Tao being gimmicky when in fact the linked piece posited him as a fulfillment of David Foster Wallace’s wish for a writer who was, as the essayist puts it, “bilingual in both irony and sincerity […] able to engage a post-ironic audience without need of the essentially terminal narrative armaments his postmodern forefathers bequeathed her (or him).”

http://bookforum.com/paper/9354http://aalrmag.org/0103reviewlin/

http://aalrmag.org/0103reviewlin/

Instead of autistic, maybe try neocon. As with a lot of conceptual writing, it’s a hell of a lot more appropriate.

Hadn’t heard of New Sincerity. I doubt that term’s going to stick. But I’m struck by how near it comes to what Frederick Barthelme does, a writer Lin loves and appears consciously influenced by, though I never see anyone mention that when talking about Lin.

This essay of FBs, “Convicted Minimalist Spills Bean,” describes the moment ~25 years ago, makes clear folks always did see minimalism as artifice, and also seems apropos of Lin today (“…if you were a trained post-modern guy, sold on the primacy of the word, on image, surface, sound, connotative and denotative play, style and grace, but short on sensitivity to the representational, what you did was drive from Texas to Mississippi and realize, while crossing the 20-mile bridge over the swamp outside Baton Rouge, that people were more interesting than words. That idea lounged on the rim of the trite bucket for a while, until it was joined by the sense that ordinary experience – almost any ordinary experience – was essentially more complex and interesting than a well-contrived encounter with big-L Language.”)

http://www.nytimes.com/1988/04/03/books/on-being-wrong-convicted-minimalist-spills-beans.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm

I should point out here that neither Mister, Missey, nor myself have ever been publicly dismissive of Language Poetry. (Well, I can’t completely speak for them, but as they’re my friends I think I’d know if they were anti-Langpo.) Wondering then, how you formed this conclusion. “MFA poetry” on the other hand, was often used as an “example” of what was “wrong with poetry” or as a way to comment upon the commodification, and hence the dilution, of art, particularly in poetry of “the time.”

It also bears mentioning that while Mister, Massey, and I more or less branded ourselves “The New Sincerity” it was a very loose affiliation–to this day, I don’t think any of us would agree on a single definition or codification of “what NS is/was.”

The problem with “working within tradition” is that it’s akin to neoconservatism, just like being a faint echo of a Hemingway novel is not that different from being a faint echo of a Rick Santorum stump speech in terms of what gets leftover when you remove any artifice.

What’s new about Lin’s work isn’t its listlessness or constraint, it’s his and others’ radical conservatism, though I doubt it’s intentional, or if it is, it’s ironic. What Lin is brilliant at doing is not bringing us a literary tradition in a new light, but bringing us the linguistics of advertising, press conferences, and stump speeches in a literary light, reformatted as gchat (etc.). And the language in those forms is inherently cynical, not sincere, because its use value lies in (self) promotion, not in (self) expression.

Hi Anthony,

My apologies, and thanks so much for the correction! My mis-impression stems from Massey’s original “Eat Shit!” manifesto, with its railings against theory- and Marxist-derived poetry; as well as later writings of his, such as “Do you remember The New Sincerity?”

Perhaps an understandable misreading? But I should have attributed those sentiments to him and not to you or Mister; again, my apologies!

I absolutely understand that your original NS formulation was ad hoc and short-lived, and that it quickly migrated to other poets/writers. But nonetheless, just as you appropriated the term from the 1980s Austin indie-pop scene, it has now been appropriated by others, and for better or worse it refers to a wide swath of contemporary poets. I wouldn’t want to claim that my above list of “moves” is definitive, but just as it once made sense to define how Daniel Johnston and Glass Eye once differed from Flock of Seagulls, I think it also makes sense to (broadly) try to define today’s NS scene against, say, MFA lyricism and/or the Conceptual Poetics scene. Because, you know, “it jingles and it jangles.”

Kindest regards,

Adam

The term’s actually stuck for quite some time now! It’s been around since the mid-1980s at least, though it’s one of those terms like “New Wave” that keeps meaning different things. Although at the same time it also revolves around a somewhat stable core…

Thanks for the link!

Hi Adam,

To be honest with you, I didn’t know there really *was* a NS scene of today. I sort of dropped out of “poetry land” for a few years. What I noticed shortly before I left was that a number of “up and coming” poets began to use the term NS to mean…well, I’m not sure. To be sure, though, the NS as first conceived by Andy Mister and me, wasn’t really anything “new” at all. Knowing Andy, he probably did appropriate the term from a music scene. I knew it wasn’t an original term but it seemed the most fitting for what I was talking about on my blog back in those days. I was interested in discussing “period styles”–

I proposed that we were beginning to see a new period style that was mostly a backlash against what I saw as a certain bloodless irony in contemporary poetry. Now surely one can blame “postmodernism” or langpo for steering us in that direction, but that is certainly not the whole story. For me, Language Poetry was immensely valuable in that it opened up possibilities that simply hadn’t been there before, or at least hadn’t been present or visible to the mainstream. Make it new, you know? At the same time, though, poets coming up in the 90s, MFA poets and the like suddenly seemed to become allergic to the personal. The lyric I was dead. Problem is, nobody managed to replace it with anything very interesting.I am resisting the urge to name names. But you know what I mean.

So, NS began with a conversation, continued with a summer’s worth of blog posts on my now defunct (but archived) blog, Geneva Convention, and became known more widely because of Massey’s tongue-completely-buried-in-throat manifesto.

These three iterations of NS were really only related because we were friends.

Anyway. Interesting post. Look forward to more.

Tony

With all due respect, I don’t think your first paragraph makes any sense. “Akin,” really? So the entire literary tradition is…like neoconservativism? I assume you’re being hyperbolic. (Isn’t commenting at HTMLGIANT conventional by now? And aren’t you also operating within the tradition of hyperbolic satire? Does that make your comment neoconservative?)

I just don’t see how any of this, Lin’s writing especially included, has anything to do with the contemporary GOP. When I talk about tradition, I’m talking about what aspects of literary form Lin’s writing conserves. As in, like, its relation to 1960s—80s minimalist realism. Which itself relates to the Modernist realism of writers like Hemingway, which relates to the avant-gardist urban traditions of Stein and the French Symbolists. None of which, I’d maintain, has anything to do with Rick Santorum, whose office in Scranton I used to make obscene gestures outside of.

Cheers,

Adam

Hi, Tony,

Again, this is all very clarifying, and I really appreciate your chiming in!

I continue to hear the term “the New Sincerity” applied by many critics and writers to all of the authors I mentioned above, from you three to present-day writers like Marie Calloway. Like all terms I suppose it’s destined to have a life of its own, and probably a fragmented one at that. Although I think it’s also a pretty useful one, as far as terms go. (Much better than “New Wave” or “postmodernism”!)

I suppose if anything I would consider the New Sincerity (again, broadly speaking) a kind of neo-Romanticism. And I find that compelling. I consider myself very much a neo-Romantic, and think the New Sincerity (such as it is) one of the more vital and welcome forces in contemporary US letters.

And I agree with your claims about Language Poetry, which it seems to me is mostly responsible for the current revitalization of US poetry. Everyone, from Conceptualists to MFA lyricists to New Sincerists has been prompted to respond! (And rest assured that in the future I’ll be more discerning in my comments regarding your attitude toward Langpo!)

I’m a doctoral student at UIC, where Professor Jennifer Ashton’s current writings about all of this are well worth reading. (I just completed a seminar with her on the past decade of US poetry.) I can direct you toward some of her essays if you’d like. I actually have a bunch of the blog posts you mentioned; Prof. Ashton has archived them.

Kindest regards,

Adam

Ha!

Parataxis forever, Richard!

I really do want to hear more about this neocon theory of yours, and how it relates to NS and conceptual writing.

Thank you for writing this smart article. I have followed Tao Lin’s writing and thinking since 2005. I find him brilliant, original, and philosophically consistent in his view of life, culture, and suffering. Anyone who tries to imitate Tao Lin, immediately gives it away, by imitating only the form, not the philosophy. And the philosophy is impossible to imitate consistently, unless one “wears” it. A careful reading reveals that Tao Lin does not use terms such as “should” or “must.” He does not judge other writers. He uses non-judgmental language. He has empathy for other living creatures and species. He does not say something is “better” or “best” or “worst.” Everything depends on context. Tao Lin’s blog reveals his thinking, and he is thinking a lot, about life, culture, and suffering. The only imitators of Tao Lin who succeed in sounding like him are most probably Tao Lin’s own heteronyms — which I will not reveal, but they tend to have lots of double consonants in their names… He is brilliant, he has created his own following! I am a fan, and have always been.

More simply: writing like Lin’s treats language and literary writing as valueless other than for the means of self-promotion. That’s about the same amount of value a neocon would attribute to literary writing, but Lin et al. save them the trouble. So I guess if not “neocon” then at least a kind of naked self-interest and deskilling that feels very old vs. very new because we’ve seen it all in the last fifty or so years of marketing and politics.

See my reply above, but in any case I’m more worked up about the idiot use of autistic to describe any of this stuff. Books aren’t autistic, people are, so it’s like describing Lin’s books as “really Asian” books–makes no sense–but if you want to read a book that reads as autistic and is valued in the community look no further than Infinite Jest. That’s autistic: hypercomplex, overwhelming, irreducible. I have a whole reception mimesis model of autism and writing directly counter to NS but it’s tangential to all this anyway.

Thanks! I don’t know if I’ve ever called any writing autistic, but you make a solid case for not doing that in general. I don’t think I’d been aware until now of the potentially offensive aspects of such a claim.

I guess I have to disagree with that :)

I plan to write more about Lin, and hope I can convince you and others that a great deal of his writing is valuable. Though I’ll be open to arguments otherwise. Though I also think I’m right! :D

(I was thinking earlier today that emoticons that use a capital D to represent a smile are my favorites. And I think that above paragraph an appropriate place for one.)

Cheers,

Adam

Hi Adam,

Thanks for this. I actually would like to know more about Ashton, direction to her work, and also this seminar, which sounds very interesting to me.

Tony

It will be my pleasure! I just sent you a friend request on FB (at least, I think it was you). I’m Adam D Jameson there.

I think you’re talking about reinforcing power structures communicated traditionally — which happens unwittingly when one doesn’t realize the ineluctability of tradition.

It’s within the history of political economy that revolution is provoked by materially changing conditions–and by critical thinking which tradition puts pragmatically at-hand.

Consider Marx’s relation to contemporary apologetics for authority rendered conceptually vestigial by progressive political economy – Smith’s – but subsequently reactionarily recuperated by the previously revolutionary bourgeoisie:

Marx’s proletarianism stands on the shoulders of bourgeois revolution, completing it. That is ‘Hegel standing on his feet’, and that is the concretely actual in “tradition” made conceptually potential, as it were, so as to be actualized concretely in a final or permanent political-economic revolution — a revolution out of political economy.

In this way, Gadamerian “tradition” does not ‘conserve’, but rather, discovers what had always been shelled up within the extraction of value from labor: people who do the work actually enjoying the world they make.

“In twenty more years, Lin’s writing, as well as most New Sincerist

writing, will look just as mannered and artificial as the minimalist

realists of the 1970s and 80s—Raymond Carver, Ann Beattie, Amy Hempel,

Joy Williams—do to you and me.”

Hmm…I’m not so sure about this. Is minimalist short story writing really that mannered today? It’s still the predominant mode in American short fiction. I could easily see “Cathedral” being published for the first time in the next issue of The New England Review. In general, today’s American short story is “minimalist.” I mean, look at the popularity of flash fiction online–most of that stuff is definitely “minimalist.” I don’t think people have beef with Lin because he’s a minimalist, esp. when even the most experimental venues favor writing that is more minimalist than maximalist. I’m not going to get into why I dislike his work here, because that’s all been done to death, but I feel confident that my dislike has nothing to do with his preference for the American short story’s predominate mode.

I don’t have anything to add to the discussion… i just wanted to say that i’ve very much enjoyed reading this and the pieces you’ve written here and on Big Other about Shklovsky. I know very little about literary theory had just read a bit here and there but i’m now wanting to learn more and will definitely check out Shklovsky and get a copy of Theory of Prose.

Also, i didn’t care much for Tao Lin and his ‘peers’ before but i’m now rereading with a new perspective and have gained more of an appreciation for his writing as opposed to a simple interest.

I like this conversation

I like this conversation

Never thought I’d see the day when Joshua Cohen is called a “Traditionalist.”

This was a great essay. Thanks for linking to it. I’m assuming that your title, “Convicted Minimalist Spills Bean,” was a typo on the actual one, “Convicted Minimalist Spills Beans,” but yours is quite a bit funnier.

William,

“…Bean” is the original title. The Times are in error. They got it wrong when they posted to the web. A copy editor no doubt changed it.

one of my favorite essays. nice to see it not just in front of me.

“The lyric I was dead. Problem is, nobody managed to replace it with anything very interesting.”

amen brotha

Not sure Lasky really belongs in this group, being sort of grandmothered-in as part of NS when it seems clear that she has stronger ties to the Gurlesque.

who is “josh”?

Good article! Disagree on a couple of points though:

1) That Lin is ‘New Sincere’, or even that ‘New Sincere’ is the cultural

dominant now. People often confuse artistic trends for

cultural-dominants, when one can choose actively to go along with an

artistic trend, whereas any activity going on within a cultural-dominant

is necessarily reacting to it, whether positively or against it. I

would argue that we are entering a period where the cultural-dominant of

postmodernism in the West is coming to an end. Across the academia

French theory has left it’s mark everywhere, but no longer holds any

claims to the zeitgeist. Stuff like the ‘End of History’ is just

demonstrably false what with how politicized everything is getting.

Within art postmodern pastiche and irony is loosing its glossy status.

There’s lots of good work about ‘what comes after postmodernism’ going

on at the moment, stuff like Alan Kirby’s book Digimodernism, and the

theory of Metamodernism, which seems the most pertinent here.

Basically though, to describe Lin as ‘sincere’, implies some sort of

retrograde run from postmodernism, back to an uncomplicated modernism

with a naive belief in ‘authenticity’, the unified individual etc. etc.

Actually what Lin is doing fits in with broader trends across culture,

such as in Wed Anderson’s cinema, and even shit like the Occupy

movement, where your seeing a mixture of postmodern detachment and irony

with the DESIRE for sincerity, the search for truth etc, even with the

awareness that such things always escape one’s grasp. To call Lin

‘sincere’ to my mind links him with someone like Jonathan Franzen, who

would like to turn back the clocks to before postmodernism every

happened, who would like to ‘return’ somewhere, whereas Lin’s (my)

Generation, having grown up fully within a postmodern paradigm, instead

move /through/ it, picking up habits likes irony, citation etc but

trying to move beyond them. Sorry it that’s a bit abstract.

2) That innovation isn’t important. It two hundred percent is and I wish

everyone would stop saying this. Obviously everything is a mixture of

innovation and tradition, obviously not everything which is innovative

is good, and not everything that is good is innovative. Obviously

everything has antecedents. But innovation, in and of itself, the

creation of NEW forms, NEW genres, the creation of NEW cultural matter

which can latter itself by cited by successors is, in and of itself, a

good thing, is in and of itself, one of art’s most Utopian

possibilities. The 2000s was a black hole for innovation across the

arts. Think about what it means to dress like someone from the 60s? 70s,

80s, even 90s (rave)? Now imagine someone dressing up like someone from

the 2000s in twenty years. They couldn’t, because the 2000s was defined

by an 80s revival that lasted longer than the 80s, and the total

dominance of vintage pastiche. Think of the amount of brand new genres

which were created say, in the 80s? New wave, Dub reggea, Post-Punk,

Hardcore, New-Jack Swing, Electro, House, etc. even the 90s had the

entire Rave explosion and all that amazing utopian energy and countless

genres which came from that. The 2000s had what, Dubstep, Grime, in

terms of innovative genres, then a whole lot of revival scenes. That

sucks. We should know that sucks. We should aim to create our own

culture, create new traditions, for prosperity.

3) That Tao Lin isn’t innovative. He is! Of course he has anticedents in

minimalist literature, but the point is that he got that tradition and

fused it with an internet vernacular, /misremembering/ it. The proof of

his innovation is that a new generation of writers are copying /him/ ,

and not his influences. Innovation is when you get influences and warp

them so much they become a unified whole. Innovation is where you bring

influences from one medium into another (Internet stuff into novels,

Impressionist Painting into novels in Gertrude Stein’s case). Some

combinations of influences are nothing but the sum of their parts

(Electro + House = Electro House), whereas other alchemically fuse into

something ultimately different (Country x Blues to the power of Jazz =

Rock n Roll). I would argue that Lin occupies a spaces coming out of the

minimalist tradition, but into something altogether different.

Thanks for those observations! Yeah, I’m always surprised when I see people not taking his work seriously. But I think that tide is really shifting.

I think a lot of people can see the style now—especially the clever people who read this site. :)

I know that, among my circle of friends, we all think Carver looks stylized as hell. (One of the best conversations I ever had with David Foster Wallace was on that very subject.) (That is not to imply DFW was in my circle of friends; I studied under him at ISU.)

Although of course as you note there are folks out there who think otherwise, who think all the parataxis and repetition and white space breaks in Carver feel like a transparent window onto drunken Pacific Northwest life itself.

Thanks!

I think Josh is many things, and I don’t want to imply that anyone is ever just one thing. My banners are meant in cheeky fun—a riff on the Inception posters. Though I do think Josh is being very traditional in his argument here: he’s rejecting Lin’s work on that basis that it doesn’t adhere to a particular literary tradition. Which I find somewhat surprising, given his other interests.

I should add that I know Josh and like him and his work in general. I’m not trying to pick on him; I’m disagreeing with the arguments in this specific review.

That’s a good point. I think people cross over lots of different groups, and that’s a good example of that.

Me, I feel influenced and inspired by the New Realism, Conceptual Poetry, Language Poetry, MFA lyricism/realism, and more, and think my fiction and poetry bear traces of all of that. If such a thing is even possible.

Joshua Cohen.

Hi Dominic,

Thanks for the comments!

1) I definitely don’t think that the NS is “the” cultural dominant now, although it is one. It’s a scene or scenes or a body of styles (devices) that a lot of writers out there are employing. I think it makes sense to talk about Tao Lin as a part of that scene. But I’m not trying to argue for some rigid or eternal taxonomy; I just think it makes sense to think like this for the purpose of this post.

Postmodernism, that’s a complicated one. I tend to think of it less as an aesthetic style (although a case ca be made for that of course) and more as a cultural condition, as Frederic Jameson described. As such, everyone is pretty much in it, or whatever is currently replacing it. As such I think it makes sense to keep it distinct from aesthetics, though there’s correlations between the two. Put another way: both Raymond Carver and Donald Barthelme were writing at the same time, during postmodernism, and while the time and place they coexisted in doubtlessly influenced their respective bodies of work, aesthetically I don’t think it makes sense to call them both “postmodernists.” They pursued different aesthetic agendas, and wrote with different purposes. And as such they obeyed the sway of different dominants, though there might be some they shared (they were both “minimalists,” in that their work tended toward the minimal).

I don’t think sincerity necessarily has anything to do with modernism or postmodernism, although I’m aware many out there do. The New Sincerity, for instance, in its original vocalization (Massey’s manifestos) did seem to be a rallying cry against “postmodernist irony.” And a lot of folks after that spent a while arguing on blogs over whether he was being ironic or sincere. Me, I think the irony/sincerity argument is a dead end. Because I’m a formalist, and so for me, if a work “feels ironic” or “feels sincere,” then that’s the result of aesthetic devices that the author is employing, and not an issue of whether the author really is ironic or sincere. I can write a poem about the death of my dog that makes people cry, despite the fact that my dog has not died, because I have never owned one. This is a roundabout way of saying that I don’t think that a return to the valuation of the devices that “feel sincere” implies at all any kind of return to modernism, either as a style or as a cultural condition.

“what Lin is doing fits in with broader trends across culture,

such as in Wed Anderson’s cinema, and even shit like the Occupy

movement, where your seeing a mixture of postmodern detachment and irony

with the DESIRE for sincerity, the search for truth etc, even with the

awareness that such things always escape one’s grasp.”

I think I agree with that, and don’t think it argues against anything I’m saying here.

To quote my good friend Jeremy M. Davies, “Ask me to be sincere and I will answer that sincerity is a rhetorical mode.” The New Sincerity is an aesthetic style that gives the impression its writer is being sincere/naive/straightforward. Whether the author is or isn’t actually that is another thing entirely. (I’m sure some are, some aren’t.)

Franzen is just usually wrong about everything.

2) “That innovation isn’t important.”

This I would never claim anywhere, and don’t think I ever have!

3) “That Tao Lin isn’t innovative.”

This also I would never claim.

I think we’re actually in agreement about everything, really, except the postmodernism stuff.

Thanks again!

Adam

you refer to him by a diminutive of his first name to convey the full weight of your disrespect

No, I know him personally, and it felt odd to me to refer to him throughout as “Cohen.” No disrespect whatsoever was intended.

Adding, I’ve written some already on the dominant, in case that interests or clarifies my interest in that concept.

At Big Other:

The Dominant and the Longue Durée

The Dominant, ctd.

Alternative Values in Small-Press Culture

David Foster Wallace, on Television, on Television as the Dominant

Here:

“A Dozen Dominants: The Current State of US Indy Lit”

A Dozen Dominants, part 2 (aka, “You used to know what these words mean”)

Cheers!

Adam

Also, I respect Josh quite a lot! Isn’t it respectful to engage someone’s ideas critically? I just disagree with him on this matter is all. And the next time I see him, I owe him a drink.

well i guess that’s ok then. i was just kidding (almost said joshing) anyway. i really liked this article a lot.

“MFA realism” = a term I am going to throw around in workshop this fall AS MUCH AS POSSIBLE. Any time someone says “I can’t figure out what’s going on in this poem,” or “Is anyone else having trouble with the pronouns?”

I think there’s a big difference between “seeing style” or even “stylized” and “mannered.” The latter is pejorative and implies that the style overrides substance. I would hope to see style in any good piece of writing, assuming it’s actually doing something other than staring at itself in the mirror.

I missed this and haven’t replied partly because you know what you’re doing I generally am not sure but I was also thinking more sociology 101 in terms of the historical pendulum swing between Hemingway and Faulkner you could carve out of the last four decades if you want to in terms of how political and social eras foreground writing parallel to them so the most critical noise gets thrown that way, and obviously there are exceptions to this rule:

’70s: turbulence and paranoia: Gaddis and Pynchon

’80s: new conservatism’s “people first” and shiny surfaces: minimalism and Ellis et al.

’90s angst, tech explosion and conservative liberalism: David Foster Wallace

the last decade: neoconservatism’s radicalized simplicity: The New Sincerity

It’s a model that has a lot of holes in it because of constants like Roth or Updike or Oates as well as Gaddis and Markson but you get the idea. Plus I don’t mean Lin etc. promote neocon values but that their writing adheres to some of the same formal principles, like oversimplification and performed sincerity.

And in all this I’m not even saying Lin or other Newly Sincere writers or their writing are good or bad because I’m not a value-judgment kind of person even though I review books here; I’m trying to get across a cogent idea of why this kind of writing, good or not, makes a trenchant Faulknerian like me a little nervous because of the radical nature of the New Sincerity’s *formal* tenets.

Plus it’s impossible to write sincere books just like it’s impossible to produce a sincere photograph or album or ballet piece so it’s all a little goofy to begin with.

This is a late reply and see my reply to Anonymojo above because I meant this in simple terms vs. terms that come from a complex working-out of the relationship between writing and politics, but one more thing is that what I get from neocon labor is that shaping the message and promoting it is more important the message (because the message is whatever serves the purpose at the time) and I get a bit of that from The New Sincerity and strict Conceptual Writing because it’s the same deal. No one else would probably link the two kinds of writing but it’s a matter of surface over meaning, and I’m not arguing Lin et al. promote or embody the message of neoconservatism at all, just the form. This has a lot to do with my probably wonky Hemingway-Faulkner pendulum swing model described in a reply in my earlier truculence a few comments above this.

And I also need to say that my review of I’ll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women appearing here soon gets a big thumbs-up so formal nervousness doesn’t mean I’m completely shunning something, even though I have some doubts about whether or not I want to sit around and read more New Sincere writing vs. everything else I want to read.

Last first: I don’t think ‘sincerity’ is impossible. It might be wrong to predicate it of a book, but of a writer? of the way a text tells true things or false? For pragmatic instance, a person describes a car you’re considering buying from them; “sincere” would be the relation of their claims to what they actually are convinced of about the car. Okay: a happy ending to a story: does it feel organic (in an old-fashioned jargon), or does it feel tacked on so that you feel ‘positive’ about consuming the story as a whole? I think “sincere” is – or could be – a useful parameter.

Maybe ‘integrity’ or ‘truthfulness’ are better terms.

I saw your Hem/Faulk polarity earlier (before you scrubbed it). It’s a shop-worn dichotomy, but I think it’s effective — and you presented it well.

Spare v luxuriant, descriptively: clipped, informatively bare sentences or plush, hyperexplanatory ones.

Of course there are other modalities; the lyricism of Gatsby (or Salter) is neither pared nor exfoliant, and (Cormac) McCarthy is both unadorned and lush by turns.

To me – an eclecticist – , neither pushes out the other.

I’m also still not sure, or persuaded, of Hemingway actually being more “traditional” than Faulkner, nor of the epigones of either being less or more confrontational towards received truth than the others.

I also think slogan-oriented language can be used to pierce and contradict comfortably routinized discourse at least as much as the novelties of descriptively extravagant language.

Am I Tao Lin?

I agree. But my point was that, as time passes, older work often looks increasingly stylized. There is always something in the present day that looks more common/familiar…which is why the present day has a look (or many overlapping looks). Later, one often sees that in a more distanced fashioned.

Also, I myself don’t use “mannered” in a pejorative fashion. (Though since many do, I should probably always clarify that.)

Cheers,

Adam

I’ll look forward to that review, Nicholas!

I just wrote a paper that argues for one or more ways in which Dorothea Lasky’s Poetry Is Not a Project is making an argument compatible with—and not at all opposed to—Conceptual Poetry.

A

Thanks! You might enjoy this conversation with TL: http://marieantoinettebadhairday1793.blogspot.com/2009_10_01_archive.html

Fair enough. I think of the term pejoratively because I first encountered it in John Gardner’s “On Moral Fiction” as a young 20-something.

And can someone please define sincerity here?

Gardner uses every term pejoratively :)

[…] wasn’t surprised that my Monday post, which was ultimately about reading & applying some ideas from Viktor Shklovsky’s Theory […]

[…] wasn’t surprised that my Monday post, which was ultimately about reading & applying some ideas from Viktor Shklovsky’s Theory […]

[…] claimed (here, here, here) that one thing at stake in the New Sincerity is the discovery of what maneuvers […]

I think you should reconsider lumping Dottie Lasky in this group, as she’s a poet with deep connections to the avant garde and experimental poetics, whatever those meaningless terms mean, but they do point to an aesthetic. She’s playing around with confessionalism in her poetry, but I don’t believe her work is confessional. Like Kathy Acker’s, it’s a brilliant invoking of cultural and emotional and personality tropes. I embrace Dottie Lasky as one of my kind.

[…] to Shklovsky! In Part 1, we examined his fundamental concepts of device and defamiliarization. In Part 2, we saw how context and history deepen what defamiliarization means. (That’s what led us to […]

[…] Theory of Prose & better writing (ctd): The New Sincerity, Tao Lin, & “differential percep… […]

http://depositfiles.com/files/t6vzg9wxxjust read that thing

instant delete

[…] 28 May: “Viktor Shklovsky wants to make you a better writer, part 2” […]

[…] yes, dear God, I know I’ve already written a ton about the guy (here, here, here, here, here, and even more yet elsewhere), and so I won’t bore you by rehashing it all […]

[…] Shklovsky’s principle of “differential perception,” which I wrote more about here and here. (And, yes, later in the story I worked in some alternatives to this repetitive structure, […]

[…] 最后,关于这个鸟人的风格,已经有很多评论,有些还十分学院化。我对文学理论或者流派兴趣不大,因此在这里就不搬运像什克洛夫斯基的陌生化(defamiliarization)、新诚挚(New Sincerity)、新童心(New Childishness)这些东西了,决定就不精确地称之为New School。我觉得在形式或内容上“新奇”已经很难,在形式和内容上都很“新奇”那就更难了,而林韬在这两个方面都做得不错。 […]