“These are poems that need to be written” — (More on the Abramson Debacle)

In the Los Angeles Review of Books’ online Marginalia Christopher Kempf breaks, I guess, some new ground on the Abramson Debacle (ie, about Seth Abramson’s 14-hour poem, Last Words for Elliot Rodger):

1) The main thrust of Kempf’s essay (borne out of looking at and discussing Abramson’s poem “as poetry, as an aesthetic work demanding, as all serious art does, the careful critical attention that lies at the heart of the literary discipline”) is that poems should be written in response to tragedy but “they need to be written well.”

2) Kempf completely dismisses Diamond’s Flavorwire post because it “ultimately prohibits any aesthetic response at all to tragedy.” He is, on the other hand, more sympathetic to Laura Sims’ VIDA article because she “explore(s) in necessary ways the relationship between art and violence, helping advance the conversation about how writers can ethically and effectively engage with tragedy” but is concerned hers is “a rather conservative position with respect to art and culture” and that “(her) remarks perhaps too closely police, at least for (his) taste, who can and cannot write about violence and how.”

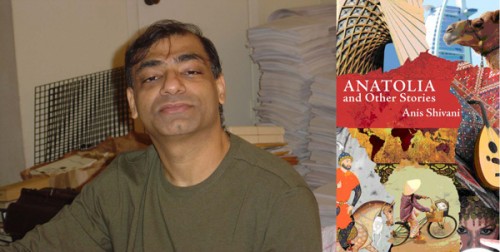

A Conversation With Anis Shivani

I am always fascinated by people with whom I disagree, vehemently and sometimes violently, about matters of mutual interest. I have read some of the literary criticism Anis Shivani has written for The Huffington Post and in other venues and regardless of his subject matter, I always have a reaction, usually a reaction that is anything but subdued. Nine times out of ten, I disagree with what Shivani has to say about everything and anything. I suppose that is the mark of a critic who is doing their job effectively–inspiring a reaction, a conversation, a response to their ideas. I am especially curious about what makes Shivani tick because he seems so committed to his opinions on the one hand, and so committed to provocation on the other, though, as you’ll see, he would disagree with that latter statement. I don’t know that you can ever really know how someone thinks or what motivates them but I asked Shivani a few questions about contemporary literature, criticism, the role of the critic, and how he approaches his critical work. He had, as you might imagine, a great deal to say and I disagreed, as you might imagine, with much of what he had to say but as ever, I had a reaction, a response and we had an interesting conversation.

You do a lot as a writer–fiction, poetry, criticism. What is your first love?

Fiction has always been my first love. I write criticism to learn more about fiction. I could also easily have devoted myself to poetry, but although poetry is satisfying in its way, only in fiction does my soul fully engage. There’s no rush like writing fiction, and I can’t do it on autopilot, as it’s possible to do with criticism or even poetry at times. The feeling of euphoria and satisfaction from writing fiction is incomparable. Writing a successful novel is a great challenge, and you have to be a bit of a poet, a bit of a critic, a bit of a dramatist, a bit of a philosopher, a bit of a social scientist, to pull it off. Writing long poems is more exciting than short lyrics, but then one needs a lot of commitment for that. I’m in two minds about having written so many stories early in my career; on the whole perhaps it was a net loss, because I didn’t spend that precious time writing novels. The economics of publishing dictated that I write short stories for many years and get them published in the literary journals, but the story requires a different mindset than a novel and it’s difficult to get the story’s habits out of the mind when one is writing a novel. It teaches compression, which is both a virtue and a fault.

It’s only an unfortunate specialization that limits writers to operating within narrow genres—short stories about a specific region and milieu, for example, or novels dedicated to the same few characters, or lyrical poems relentlessly exploring one’s own ethnicity or geography—otherwise writers in other countries still write in different genres at the same time, and this has always been the case since the beginning of time—until, that is, the academic specialization of literary writing under university patronage in the U.S. in the late twentieth century. I think writers should see themselves as workers in the broad field of the arts—including even Hollywood or popular music, and certainly what used to be called literary journalism in every possible genre. Anything to break the rut, to push the mind toward new challenges so that writing doesn’t fall into preestablished grooves—which is very easy to do, based on the successful formulas in existence. Film is a particularly fruitful cross-fertilizer, as is painting. Really, the arts cannot function in isolation and shouldn’t be practiced and critiqued that way. It’s only unprecedented specialization that has created this unnatural situation, and the writer must be very conscious of that and work hard to break down the false institutional barriers preventing a catholicity, even eccentricity, of interests. The mind desires to switch between different levels of intuition and emotion and logic and these desires should be fed.

June 22nd, 2011 / 4:39 pm

Amelia Gray makes sense out of the Publishers Weekly and WILLA kerfuffle at the Huffington Post: “To vastly extrapolate, assuming that the number of top-quality male and female writers is equally distributed, most journals would publish more men than women, without even considering bias.”

Wouldn’t it be awesome if Hank Williams III [Update: Turns out it was junior in the picture. My bust.] turned out to not actually be related to the legendary Hank Williams I and instead turned out to be the illegitimate son of Marge Schott and dog shit? Because I think that would be awesome.