Author Spotlight

A Few Questions for Edward Mullany

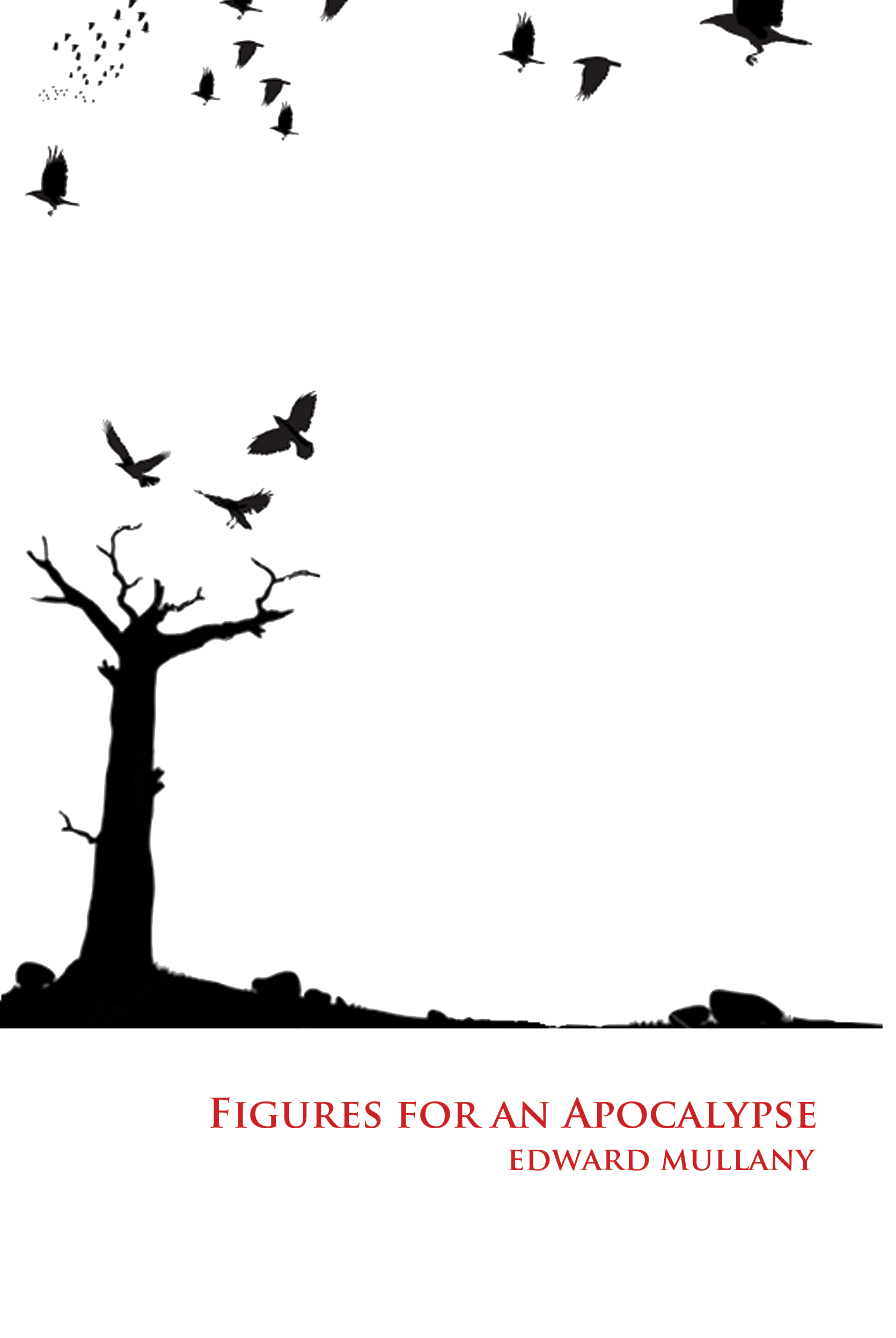

This week Edward Mullany’s second book came out on my own press, Publishing Genius. It’s called Figures for an Apocalypse, and the stories in it (and poems that tell these stories) exist on the perimeter of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, before and after the inciting incident. Like there’s one called “The Parade of Rabbits” that goes “No one // saw it. /// It happened / after everyone died.” I read Edward’s manuscript for the first time last summer, while I was on an Adirondack camping trip with my family. Lots of kids, so I floated out on a kayak on a still pond. By the time I drifted to shore I’d read it through and thought it was the best possible setting. In the intervening year and a half I’ve read the book in handful of other settings—at my desk, on the john, on the road, in long and short sittings—and every different setting also seemed ideal. Part of the magic of everything Edward does, I think, is how he brings the reader/viewer into his own mindscape. I asked Edward a few questions.

Is there humor in this book?

Yes, though not much. But it’s important that it’s in there. If the book had no humor in it, it would lack resonance because it would indulge in a pessimism that isn’t real. The only place that I can imagine humor being impossible is hell. Like, the actual “eternal fire,” in a religious sense. And I’m not trying to tell a story about hell. What I mean is that the book is trying to tell a story about the human situation as it exists in temporality (as opposed to eternity). And there is always the possibility of humor in this situation – the one that exists in time. In the same way that there is always the possibility of hope. Not hope that we won’t suffer or won’t die, but rather hope that our sufferings and deaths can have meaning.

There are a lot of similarities in the form of this book and your first. How is Figures different from If I Falter at the Gallows?

It might have a more obvious narrative arc. It has more unity, in that each piece describes, in some way, an apocalyptic territory—whether that be physical or emotional. So that the title of the book can be understood as a way of recognizing what’s inside—each piece becomes a “figure” in that apocalyptic landscape. But the books are the same in that they originate from the same preoccupations. They’re like brothers. The phrase “spiritual paranoia” could apply to them both. Both books are aware of mortality, sin, love (or the absence of love), violence, angst and regret.

Some of the pieces in this book are a couple pages long. What comes first the subject of the poem, or the form?

I think they usually build or define each other. I mean that I discover what each poem is about as I write it. Sometimes I write a title first, and then discover what I mean by that title through the writing of the poem. And sometimes I write a piece, and realize only afterward what title it ought to have. There are exceptions in the case of very short pieces. For example, there is a poem in the first book called, “The Horse that Drew the Cart that Carried the Condemned Man to the Gallows.” I wrote that title, and then realized that the poem that belonged to it was already in my mind before I’d finished writing the title. The poem goes: “lived for a while longer/and then died.”

What can you tell us about the third book in this series?

When I think of the third book in this series, I think of the three colors of the first two covers – red, white and black. This is helping me form an idea about what the third book will be, and how it will relate to the first two books, regardless of what it is “about”. I mean that all three might really be about the same thing thematically. One of my favorite movie directors is Krzysztof Kieslowski, who was Polish. He made a French/Polish trilogy called The Three Colors. The three movies comprising it were Blue, White and Red, which correspond to the colors in the French flag. And all three involved characters who were searching for meaning or for love. And though they succeed as individual films, independent of each other, they also create a cumulative power, when considered beside each other. And they interweave in very real ways. For example, a character who is the protagonist of one film appears very fleetingly, sort of accidentally, in another. And vice versa. And so a perspective of the world that is both human and divine emerges. I mean “divine” in the indifferent sense—the way that a life might seem so small from the viewpoint of the planets or the sky, while to the person herself, who is living it, it must seem absolutely unique and important.

Can you send a picture of what your writing area is like?

Tags: Edward Mullany, Publishing Genius

[…] and More: Fanzine Rattle Green Mountains Review HTMLGiant Vol. 1 […]

[…] Andrew Weatherhead and Mallory Whitten. Speaking of Publishing Genius, I thought I’d take a page from PGP man (& BYWB designer) Adam Robinson’s playbook and post a quick but savory […]