Author Spotlight

From the Margins: An Interview with Peter Davis

With just two books of poetry, and a third on the way, Peter Davis has already established himself as an innovator with a great deal of intelligence and skill. Modest but assured, he explores ideas most poets would not think to broach and pushes the accepted limits of form in ways that expand what a poem can be. Whether pondering the heinous mustache of the previous century’s most infamous tyrant, or inventing satirical monologues for real and imagined audiences, Davis knows that in order to break ground a writer must be bold and open to uncertainties: “An artist has to pursue something he or she is unsure of, but then pursue it recklessly.” While these pursuits make great comic shtick, they are only half the story, for Davis’s sense of play services a unique moral vision. The text below is a collation of one face-to-face interview in April 2011 and several email exchanges from April to June 2011. – Tony Leuzzi

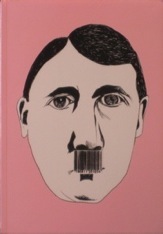

What was the genesis for the idea of writing an entire book of poems about Hitler’s mustache?

Well, I didn’t intend to write an entire book about his mustache, but that’s what happened. First, a friend of mine mentioned what a great band name Hitler’s Mustache would be, which led to the first poem in the book “The List of Facts.” But after I was done writing it, something stuck with me—namely that Hitler, our embodiment of evil, was essentially very comical looking. This made me think that his appearance was obviously very important to him (as it seems to be for many dictators). I also began to think about Hitler the failed artist who, unable to gain respect drawing and painting, decided to then move into politics and, ultimately, world domination. This made me wonder what similarities the average artist might have with a tyrant. I was writing poems this whole time. I didn’t really know what I was doing, but I was having fun.

At some point, too, I just thought: How come I don’t hear more about his ridiculous mustache? In addition to all of the major harm Hitler did, he also made this particular style of facial hair un-wearable. The dude didn’t just ruin lives—he was fucking with fashion, too! (I almost subtitled the book “An Intersection of Fashion and Fascism.”) Here was a man who was so concerned with the aesthetics of everything, who even was concerned that soldier uniforms look right, and yet that moustache! There is evidence that some higher ups in the Nazi Party tried to get him to reshape it, but he kept it, thought, “This is a good idea.” He must have seen himself as a dashing figure.

At some point, too, I just thought: How come I don’t hear more about his ridiculous mustache? In addition to all of the major harm Hitler did, he also made this particular style of facial hair un-wearable. The dude didn’t just ruin lives—he was fucking with fashion, too! (I almost subtitled the book “An Intersection of Fashion and Fascism.”) Here was a man who was so concerned with the aesthetics of everything, who even was concerned that soldier uniforms look right, and yet that moustache! There is evidence that some higher ups in the Nazi Party tried to get him to reshape it, but he kept it, thought, “This is a good idea.” He must have seen himself as a dashing figure.

Anyway, so now I was reading about Hitler. Reading about mustaches and facial hair, in general. Checking out all the beard and mustache competitions, etc. online. I said stuff to my wife like, “I don’t know what exactly I’m doing with this, but it’s a blast.” She said stuff like, “You’re a weirdo.”

But here’s another thing: At some point in time I realized that the image of Hitler’s mustache (that black square) and the word “mustache,” in particular, were beginning to dominate my imagination. The word “mustache” is such a mouthful. The image of his mustache began to seem to me to be a black hole, a square trap-door through which something is always slipping. Or to say it another way: No matter what we know about something, there is always something that we don’t know. That hole above his upper lip was a place none of us will ever know or understand. Nothing is simple. The end of every answer always results in another question. Always something unfathomable.

In an earlier discussion you told me you felt that the image of the mustache—or is it the word mustache— becomes a fascist in the text, taking over, asserting itself everywhere. Could you talk about some of the ways in which this happens in the text?

The word “mustache” became something I liked lots. When I was writing and I got to that moment when the writer pauses for a second, in air, and considers the next word—I began to think of that unknown word as mustache. So that’s what I’d write. This trick seemed to work for me. It helped me get to the next word. So all my poems had the word mustache in them. I began to see the word as something fuzzy and black as Hitler’s mustache. It became a barcode that identifies each poem as its own. This made me think of the Swastika and how the Nazi machine dominated its country with a mark, a symbol, and that symbol was meant to replace everything else: every religion, every idea, every invention. That Swastika tried to dominate Germany and the word mustache was dominating my imagination, killing off the other words that would come if I didn’t quickly squash them with my black, square mustache-hammer. And since a word is equal to an idea (at least to me) that means that the word mustache was like a fascist, squeezing everything else to death. I let it happen, for the sake of the book. This is most obvious in a poem like “The Short Story” where the words of the narrative increasingly become the word mustache, till, by the end, there is nothing but “She mustached the mustache and with every mustache of her mustache, she mustached.” Mustache was a censor, a replacement, an etc. for everything else. As a poet, it was nice to have a safety net word. The appeal of fascism became more obvious: it erases questions. Erasing questions can be a very pleasant sensation, which is part of what an artist does (or might do).

Were you concerned at any point that people might think your exploitation of Hitler would be irreverent or inappropriate?

Yes. I certainly didn’t want people to think I was making light of the Holocaust or being sympathetic to Hitler. Although most people interpret the book as comical, there is a lot of serious stuff in there. I try to have some sort of balance, so the book doesn’t come across as insensitive. The editing process helped me a lot in this regard. I wrote a lot of poems, probably 150 more than are in the book. I cut lots of them.

Some people will probably just be offended by anything involving Hitler. For instance, when the book came out, I was at the annual AWP conference for the release and doing a book signing at the book fair which meant I sat on a folding chair behind a table full of my book and watched people as they milled past the various booths just like the one I was sitting in. Occasionally, I signed a book, which has a drawing of Hitler’s face on the cover, no words, and, also, Hitler’s mustache is represented as a barcode. Some people would actually turn up their noses when they saw it. They would walk by fast and give me a look like they thought I was a Nazi. It was funny to think about it. Like, I was a Nazi and thought “Here’s how we’ll do this: I’ll write a book of poems and we’ll take it to the annual Associated Writing Programs conference…..Yes, first AWP, then the world…..” Nazis are not generally known for their efforts in contemporary American poetry.

Many of the poems are satires of well-known contemporary poets, such as Robert Bly, Frank O’Hara, and James Wright. You also allude to Stevens a few times. How does your desire to pay tribute to these writers through satire mesh with focus elsewhere on Hitler?

To be honest, most of the stuff that happened in the book is in some way or another the product of accident. When I’m writing I don’t really know what the hell I’m doing. I try not to think or reflect on my choices until later on. But as I was writing the book I did discover this strange similarity between artists and dictators—both, I suppose, wanting complete control over their given (or taken) spheres. That is why the book experiments with different forms: the idea of conforming to preexisting conditions seemed to fit with the mustache—that tightly groomed square of death. I also think of the book as being about poetry, as well as about mustaches and Hitler and fascism. So I imitated some poets who I like and was reading around this time. I mean, I love O’Hara. I think James Wright can be very beautiful. I think Robert Bly can be very fun when he’s not taking himself so seriously. Russell Edson doesn’t have the problem of taking himself too seriously. And Wallace Stevens is just really important to me in terms of how I feel about writing and my general thinking about the concept of the imagination. I wrote other satires that didn’t end up in the final book: Emily Dickinson and T. S. Eliot are the first ones I remember. I have tons of respect for all of these people. I sent copies of the book to the two poets still alive, Bly and Edson. One sent a nice note and one didn’t respond at all. In both cases, I can understand their reaction.

Your book features no less than three sestinas—all of them highpoints in the book. What drew you to this form?

Well the sestina thing goes along with the form thing. I had teacher who made me write a sestina. I was told, at some point, that sestinas were one of the hardest forms and thus I felt the need to try it. I don’t actually feel it’s a hard form to write. I like it. The repetition of the words made sense given the repetition of the word mustache (of course mustache figures prominently into all of the sestinas). I don’t really like reading sestinas, but I like writing them. I haven’t written one for a while, but they’re fun and a good way for me to step into something different for a day or two.

“Hitler Sestina” was first published on McSweeney’s, back when the only poetry they published was sestinas (one of the weirder submission policies). Daniel Nester was the editor and he accepted it and I was happy. But they didn’t actually put it up on the site. I think I e-mailed Daniel a couple of times over the next year or more saying, y’all going to put that up? And he’d say, yes, but with no details. But they did publish it on 6/6/06. 666! I was humbled by their genius and forethought. Nice work, I thought. Good job.

Many of the poems play with line and form, however the bulk of them are prose poems. Moreover, in Poetry! Poetry! Poetry! all but two or three of the poems are in prose. Why do you feel compelled to write so many prose poems? And how do you see yourself as participating in that tradition?

Many of the poems play with line and form, however the bulk of them are prose poems. Moreover, in Poetry! Poetry! Poetry! all but two or three of the poems are in prose. Why do you feel compelled to write so many prose poems? And how do you see yourself as participating in that tradition?

I like prose poems largely because I often find myself not being able to justify line breaks. The poems in Poetry! Poetry! Poetry! were written first with lots of line breaks and extravagant spacing because since the poems were largely about poetry, I thought that doing so would call attention to their “poetry-ness.” This is, I suppose, how I feel about line breaks. They call attention to the poem as a poem—which is fine, I just don’t like to do that, apparently. I think it’s more fun to read something that one doesn’t expect to be poetic (because it looks like prose) and then to find yourself in a world that is slightly different than the normal world of prose. Even though the line breaks and spacing first used in Poetry! Poetry! Poetry! were done for good reason: I eventually began to think that they’d be better in prose for precisely the opposite reason—that them not looking like poems paradoxically helped bring attention to their poetry-ness. So the book is all prose poems. Also, I like the general weirdness of the idea of prose poems and the reluctance that some people feel in reading them as poetry.

As far as how I fit in the tradition, I don’t know. I wrote prose poems in college, long before I realized there was a tradition. Once I learned of its history I felt very comfortable in that company. Prose poems seem like weirdo poems and one of my favorite things about poetry (and art, in general) is its weirdness. Certainly those poets who wrote the earliest examples of prose poems were weirdoes, in one sense or another.

Do you identify yourself as a weirdo?

Most of my life people have, in one way or another, told me I’m weird. And for a huge chunk of my life I took pride in that. When I was a kid, I felt like I was the only kid who was breakdancing, and then I was the only kid who was skateboarding, etc. In my head, I think other people are weird, but when I look around me and read lots of other poetry books, I wonder “How did I become a poet, and why?” It seems to me there’s a whole bunch of poetry that is very serious, often pretentious, and not very interesting to me. But then, you’re a weirdo in this culture if you’re a poet, period. You’re already doing something that’s very much so on the margins of what is most people’s idea of what life should be like. The majority of people don’t care about poetry—so all poets are in one way or another on the margins.

You have a website called Art is Necessary. Is this an assertion that has universal application, or are you saying art is necessary for you? Or somewhere in between?

Art Is Necessary is primarily an assertion of my own individual experience. I’ve played music, written, and made visual art for the vast majority of my life. I don’t have a good reason why this is true, it’s just the way my life has gone. I can imagine what I would do without these things in my life, but I don’t believe I could be at peace with myself or happy. Why is art necessary? I really don’t know. “My love she speaks like silence.”

Each of the poems in Poetry! Poetry! Poetry! is addressed to a reader. How did this concept come about?

First I learned of the idea of “radical honesty” which posited that we should all be completely, entirely, totally honest all of the time. The first poem I wrote had no title and was all in caps and read “I AM WRITING A BOOK” and I did want to write a book because that’s one of the things a writer does. Somehow, after writing a few poems, like “THIS IS THE FIRST POEM” and “HERE’S NUMBER TWO” (imagine these poems spread out across a page, with line breaks and spaces). I came to the idea of providing titles for poems. Soon those titles always evolved into “Poem Addressing…” So now I was making up titles too! I just kept going on in that stumbling sort of fashion forward until I finally fell down and quit writing all those poems. It’s the same way Hitler’s Mustache was written and developed. I just started with something and followed it to some conclusion. I thought about what I was doing at the time, but also not really thinking. Before I knew it I’d written a ton of shit and then, a bit before I knew, it was time to quit writing. The idea of addressing something is such a simple idea and once I started, like everything else that’s enjoyable, it became easy.

In terms of a book of poems, it seems long, almost twice as long as most individual volumes of poetry.

The book is asking for a lot of praise, asking for a lot of attention. In this regard, its length seemed kind of important: it needed to be twice as long as an ordinary book because the writer—a persona but also an extension of myself—wants twice as much affirmation and praise! Still, from my perspective, the book is short, since I wrote twice as many of these poems than what went into the book.

Underneath the humorous shtick of many of the poems there seems a genuine anxiety for any writer wanting an audience.

Most writers at heart wonder, “Why do I write? What is the point?” I enjoy the process of making the poem, the creative process, but why then do I make all the effort of trying to put them out in the world? As a writer I want validation and approval. I want to make connections with people. I want them to like me on my own terms. But getting approval through a poem or by making some piece of art is difficult. For most artists rejection is 90% of what you do. Even someone like Picasso experiences enormous amount of rejection. Think of how many people pass one of his paintings each day and say, “That’s not my kind of thing.”

Why the exclamation points in the title?

That’s the way it first occurred to me. It’s genuine excitement, I suppose. But then again, it’s also intended to be deliberately silly. I remember writing it in pencil on the wall beside my desk in the basement. Writing poetry to the degree that it eats up my life is pretty ridiculous. I do take it seriously, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t also silly.

Tell me all about the book you’re working on now. How does this work resemble or connect to the two previous books? How is this new book a departure for you?

The book I’m working on now (or am almost done with) is called Tina. It makes a great deal of the use of addressing a single person directly, in this case, Tina. I mean it’s a lot different to say, “the woods are lovely dark and deep, and miles to go before I sleep” and saying, “the woods are lovely dark and deep, and miles to go before I sleep, Bob.” The name Tina means nothing to me, or, rather, it means something to me but in a way that is so specific to my own existence there’s no use in trying to explain. (I’ve known a couple people named Tina. There is nothing wrong with people named Tina. Most Tina’s I’ve met have been perfectly decent people.) I want to say it’s similar to the other books because I’m similar to the person who wrote those books. On the other hand, I’m not the same guy I have been (while also always being as close to him as anyone else). It’s different because these poems, by and large (at least, so far) have line breaks. They aren’t prose poems. I wish I could tell you more about it, but I don’t really know much more about it. I can say that I would like to write books that are different from each other. I hope it’s a different experience for the reader than the experience of my other books. Of course, I guess, probably many writers feel this way about their work so maybe it’s not even worth pointing out. But still, I would like my poems to be distinct enough that, say, a person is reading a poem from Hitler’s Mustache—they know, just by reading that single poem, which book it came from. I don’t want the poems to be interchangeable with my other work. Why is this important to me? Well, I guess it’s because I’ve always enjoyed other artists who did that for me. Of course, all of them sound like themselves all the time, too.

Where do you position yourself in the world of contemporary American poetry? And how does this positioning reflect where you’ve come from and where you want to go?

This is a hard question. I don’t know my position and fortunately, or unfortunately, I don’t get to claim that position for myself. Only other people can position me. Me, I just make the work I make and hope that I end up happy with it. On the other hand, if I could put myself in a position that seems enjoyable to me, I would position myself outside of the front door and sort-of halfway on the lawn. I’m a parent and was once part of a parent conversation with some other poets which led to a discussion about how our poetry life has changed since having children—or, how having children changed our poetry. After considering this question for a while, I think the most important thing about being a parent has been that it even further encourages me to be a good person, one who controls his temper, is patient, forgiving, and thinks of others, etc. As an artist what this has meant is that I feel it’s even more important to make work that is somehow bolder than what I’ve done in the past, to be prouder of my instincts and more trusting of my artistic impulses. I want my kids to be happy, to have fun in life and to be decent to others. I think being a good example means trying to make good art. For me, that means art that is advancing forward to something and that usually means being vulnerable and scared. So, I want to be part of whatever world is part of the uncomfortable world. I believe in uneasiness.

To be bolder, for me, means pushing my own sensibilities so that I don’t feel sure of what I’m doing. I like the sensation when I’m working on something of not being able to decide if what I’m doing is the stupidest thing I’ve ever done or the best. In a sense I’m always out to destroy my idea of a “the poem.” I know there’s no “real” risk involved in writing poetry or practically any other kind of writing, but I like to at least be risking the possibility that I’m wasting my time. Forgive me if I’m repeating myself. Anyway, to get to this place where things are risky but something really great might happen, I think an artist has to pursue something he or she is unsure of, but then pursue it recklessly. When I say “unsure of” I mean something that feels like it might be a huge waste of time. I guess I don’t feel like all artists need to do this, or any of them, but, for good or bad, that’s what I find myself doing. And, I guess, I feel like if I’m going to spend my time working on something like poetry which is a frivolous activity compared to activities like eating and raising children, if I’m going to engage in poetry as a means of helping to define who I am, then I want who I am to be someone who is not afraid to push the silliness that is poetry (and the silliness of the world) to the extremes that I’m capable of. I think silliness recklessly pursued can result in something that isn’t silly at all, but actually maybe very serious and profound. (Not that profundity and seriousness or any better than silliness.) I want my kids to learn this: I’m trying to set a good example. And thus, there’s always a great deal of fear involved because it is not easy for me to live up to the expectations I have of myself, as an artist or as a person. There is always the fear of exposing something about myself that will make others dislike me. Either they will conclude I’m not very smart or I’m mean or I’m thoughtless or I’m boring or whatever. This matters to me because ultimately I don’t believe the work really exists until it’s exposed to other humans. Art is a social exchange and I want people to feel like they got a good deal. The only standard I have to measure whether they’ll get a good deal is by first and foremost deciding it was a good deal for myself. Kurt Vonnegut said art was “half a conversation between two individuals,” if that’s true, then I want my part of the conversation to be interesting. But I never know for sure. Like now, as I think through this answer, I think I’ve gone on too long and no one will care! I’m thinking, by now, everyone’s quit reading.

When you came to read here in Rochester a lot of students were in awe of your originality, humor, and down-to-earth personality. You must make a pretty good teacher yourself at Ball State University. What words would you give to a young student only beginning to explore his or her interests in writing poetry?

Oh, I’m glad your students liked my visit. I liked it too. Everyone was really nice. There are, as a teacher, a lot of things that I might say to a person beginning to explore his or her interests in poetry. But, I suppose, to be brief-ish, I would say: Don’t think about what you should/or are going to write, just write. Don’t think about whether what you’re doing is good or bad, just try to do something interesting, surprising. The least something can be is interesting. Have fun. If you’re not having fun writing it, few people are going to enjoy reading it. Relax. Don’t think. Relax. Poetry, like other forms of art, should be a real experience (it doesn’t matter whether that experience is pleasant of not, just that it exists). So enjoy it like you enjoy listening to a song. Just see what happens. “Just go on nerve” as O’Hara said. Oh, okay, that’d be something too: I’d tell them to read Frank O’Hara’s “Personism” essay.

You say, “Have fun” and “Don’t think. Relax.” Might a beginning writer interpret this as “I don’t have to put effort into the work, I don’t have to stretch myself, I only need to write what I wish and it will be a poem”? Or are you merely offering them preliminary advice, just to get them started? I mean, when you were starting out, didn’t you struggle a bit with this new medium, which made demands upon you that you did not anticipate when you first picked up a pen and thought, “I want to write”?

A beginning writer, or anyone for that matter, might interpret my advice in lots of ways that I don’t entirely mean, but that’s where I’d start. I don’t recommend struggle to anyone. If possible, I recommend avoiding struggle. Nobody needs to teach a person that struggle, in any pursuit, is inevitable. Life does that. If a person really wants to write, they’ll learn what’s important for their writing life. If they don’t really want to write, then it really doesn’t matter anyway. In that case, the benefit of the Creative Writing class they took wasn’t for their own writing, but for their ability to appreciate others who write (or make art, in general). Making people who will appreciate creative acts and the creative process is the largest part of why I think teaching creative writing is a good thing.

You’re also a visual artist and musician. How do these other mediums feed into your poetry?

I was musician and a visual artist before I was a writer. In fact, writing songs was the first creative writing I really did. In school, where I got terrible grades and was a very bad student, I only did well in art class. I continue to play music a lot and to do plenty of visual art. How do these things influence my poetry? I don’t know. It’s a good question and I’ve thought about it plenty of times, but I don’t have a good answer.

Probably the most direct influence these activities have on my writing is that when I’m engaged in them, I’m not writing. So they eat up some time. That’s okay though. I think of them as essentially all the same. Like my wife will say to me “Did you get anything done last night?” And if I’ve done any of the three I answer, “Yes.” I know that some people who like my poetry don’t like my music and vise versa regarding all combos of my work. It’s not like I can maintain a consistent approach through the different mediums because, like everyone, I’ve got tons of limitations in my abilities and so I don’t get to do everything the way I’d like to do it. I have to compromise with my competency. So, you know, I’m just trying to take all of my natural mistakes and present them to others as something more beautiful than what they seem like to me when I make them.

You’ve mentioned beauty more than once in this interview. I know this is a large question but how would you define beauty? How is your notion of beauty tied in to your poetry?

It’s pretty weird to me that I’ve mentioned beauty a couple of times. I don’t really consciously think of poetry as a place to make beauty, but maybe, on some subconscious level, I do think that and just haven’t realized it. To me, real beauty develops from some sort of flaw, some sort of limitation that is twisted into something new and surprising. In Poetry! Poetry! Poetry! I have a poem critical of Celine Dion and the only reason why is she’s an artist who, it seems to me, makes the most of perfection, which I think is really boring. She wears perfect gowns and sings perfect songs with her technically perfect voice and technically perfect band. My favorite singer of all time is Muddy Waters. My second favorite singer of all time is Bob Dylan. My point is that I like art that somehow uses its own flaws to elevate itself—to turn every weakness into a strength. This isn’t a new idea. I just really, really like that. Of course, as has been noted by lots of people, art that is really, really beautiful often seems ugly at first.

Aren’t you conflating “beauty” with “perfection”?

Probably. I guess I could say that the qualities that I find attractive, i.e. beautiful, would be certain types of flaws, certain vulnerabilities, certain surprises, certain moments that create unexpected happiness.

What kind of poets do you think are Celine-like in their glossy perfection, whereas which kind of poets (or poems) possess the same kind of beauty you find in Muddy Waters?

Well, I don’t have any interest in saying anything negative about any poet. I figure Celine can handle it because she is, after all, very rich and successful. There’s not a poet on the planet that’s near as successful and praised as she is. But, more generally speaking, a “perfection” poet might seek the epiphany as the perfect gown, Nature as the perfect song, and meter as the perfect band. I prefer poems with rough edges. Emily Dickinson has rough edges. So does Frank O’Hara. So do lots of people. I like those people.

– – –

Works by Peter Davis

Poetry:

Poetry! Poetry! Poetry!, Bloof Books, 2010

Hitler’s Mustache, Barnwood Press, 2006

As Editor:

Poet’s Bookshelf: Contemporary Poets On Books that Shaped Their Art, Editor, Barnwood 2005

Poet’s Bookshelf II, Co-edited with Tom Koontz, Barnwood, 2008

– – –

Tony Leuzzi is a writer and teacher who lives in Rochester, NY. His poems and articles have been published in Arts and Letters, Jacket, Sentence, The National Poetry Review, and elsewhere. Radiant Losses, his second book of poems, won the 2009 New Sins Editorial Prize. His new book, Fake Book, will be released by Anything-Anywhere-Anymore press this spring.

Tags: art is necessary, peter davis, tony leuzzi

Poetry! Poetry! Poetry! is really great.

Peter Davis is a smart and funny writer. Get Poetry! Poetry! Poetry!

Good news:

this website http://tinyurl.com/8a4vnr5 ) we has been updated and

add products and many things they abandoned their increases are welcome

to

visit our website. Accept credit card payments, free transport. You can

try on,will make you satisfied,thanks!

http://tinyurl.com/8a4vnr5

http://tinyurl.com/8a4vnr5 http://tinyurl.com/8a4vnr5

[…] Source: HTML Giant Share […]