Interview with Lee Rourke

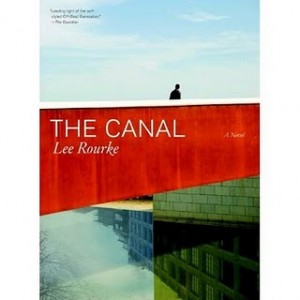

Lee Rouke’s debut novel, The Canal has just been released in the the States and will be hitting the UK in less than a month. I’ve already said good things about it & so have Shane Jones & John Wray . I conducted this little interview with Lee over email.

Lee Rouke’s debut novel, The Canal has just been released in the the States and will be hitting the UK in less than a month. I’ve already said good things about it & so have Shane Jones & John Wray . I conducted this little interview with Lee over email.

First, an excerpt, then another after the interview:

She addressed him only.

“Do you remember me?”

There was a long pause.

He looked at the woman next to him, then back at her, then back at the woman. He looked nervous, rubbing his thumb into the palm of his hand. The woman’s eyes began to narrow and her whole face started to contort. He looked back up at her.

“Er . . . I’m . . . afraid . . . I’m afraid I don’t, sorry. Er . . . Have we . . . Should I?”

“You tell me.”

“I’m sorry, I’ve never seen you before in my life. I fear you may have mistaken me for another person, someone else in your life . . . I’m sorry.”

“You’re sorry?”

“Yes.”

“You’re sorry? That’s all you can say? Sorry? Don’t you remember me at all?”

“I’m sorry, but no, I clearly don’t. I clearly don’t remember you from anywhere, I have never seen you before in my life. Now, we were having a private conversation. I’m sorry, but . . .”

“So, you just want to leave it like that?”

“If you don’t mind, I’d rather, yes.”

“No. I want you to tell me who I am. I want you to tell me who I am. You have to tell me.”

“I’m sorry, but I seriously have no idea. Can you please leave us alone now?”

“No. Do you not remember who I am?”

“No, I do not. I have never set eyes on you before in my entire life. You have clearly mistaken me for another person. Please leave us alone.”

I was beginning to feel more than ill at ease with the whole situation. The bored waitress behind the counter was leaning on her elbows, chin in palms, looking over toward them, smiling, happy to be watching the burgeoning spectacle before her, happy, at last, that something was eventually happening that day. I remember uttering the word ‘no’ twice, but it went unheard in the ensuing mêlée. I watched as she threw the glass of water over him, the plates crashing to the floor, breaking into shards and fragments, scattering across the tiles into far-flung corners of the café. The blonde woman’s deafening scream nearly burst my eardrum. The man, now soaked, his white shirt sticking to his skin, rose to his feet and pushed her to the floor. She immediately jumped back to her feet and continued her attack, swinging for his face, trying to pull his hair and scratch his cheeks. The other woman began to fight back, too, holding her, leaning over the table to grab her flailing arms, knocking it over in the process. More screaming and shrieking enveloped the room.

“You do remember me. You do remember me. You do remember me. You do remember me. You do remember me. You do remember me.”

Your narrator speaks a lot about his philosophy on boredom. How much of this do you share with him?

Well, I would have to say quite a lot. I mean, I truly believe – as Bertrand Russell did before me – that if we truly embraced boredom there would be less violence in the world. When I say truly embrace boredom I mean that we should make an effort not to fight it – we especially shouldn’t do something just to stop us from feeling bored (this just leads to the type of passive nihilism the philosopher Simon Critchley warns us about). I think we should just accept it and naturally feel bored and ultimately do nothing. Fighting boredom only leads to friction, which can cause myriad things, including the type of violence that haunts my novel. But I know this is a losing battle. It is a losing battle because boredom reveals to us the nothingness that makes up our lives: the gaping void of our existence, its meaninglessness and finiteness. Obviously this gaping void scares the shit out of us. And it is because of this intrinsic fear that we mostly fail.

John Wray said that The Canal “harnesses the power of parable,” and I have to agree. I feel like the philosophical drama the narrator is having is being acted out in front of him. How much of this were you aware of as you wrote?

There is a tangible mythic element to The Canal – and I think this is where the motif of parable ties in with it (something which John Wray picked up on immediately). I don’t read him that much anymore, but Jorge Luis Borges’ idea that ‘in the beginning of literature is the myth, and in the end as well’ was bouncing around my head as I set out to write the book. There are many myths interwoven throughout the simple narrative of The Canal, most notably Leda and the Swan, and an element of Cassandra within the woman on the bench, too – I even see the nefarious gang of youths who haunt the canal banks and the narrator from day to day as a Greek chorus of sorts. Albeit, a rather ramshackle one. I am interested in fabulist literature and I wanted to take certain traits from the Aesopic tradition; not the overtly fantastic or anthropomorphic tropes commonly found, but the simplicity of narrative structure governs many fables and myths. Greek myths are fabulous and often baffling things to read, but if you break them down and look at their structure, their myriad ideas and complex themes are often conveyed back to us by a rather rudimentary narrative – in which they act as blueprints for the bigger picture. It is the same mix of simplicity and the cryptographic that I was seeking whilst writing The Canal.

Are there really foxes and swans wandering the neighborhoods and canals in the greater London area?

Yes. Where I live in east London you sometimes see foxes walking down the streets during the day. At night they are a common sight and one visits our garden most evenings looking for food. Sometimes, in the dead of night, you can hear the foxes mating – it’s a horrendous racket which sounds like babies being murdered or something. But I love foxes and totally abhor archaic things like fox hunting. I’d seriously like a fox as a pet, but I don’t know how practical this would be as a) they are wild and free and probably wouldn’t like it and b) we have two cats that might not get along with the fox. Along the Regent’s canal in London where my novel is set you’ll see swans, Canada geese, Coots, Moorhens and even Herons. Along with the pigeons, of course, who all sit on the canal banks looking enviously at the swans paddling along in the water eating the bread that people feed them as they walk by. Oh, and lots of rats, too. I like rats.

Since a lot of htmlgiant readers are writers as well, could you talk a little about what your process was like in creating this novel?

Well, I’m rather boring when it comes to writing. I find writing extremely hard and it’s not something that comes easily to me. I write longhand in cheap notepads in pubs and cafes. I always use a Pilot Hi-Techpoint V5 Extra fine pen with a 0.5 nib. I find these easy to write with for long periods of time. I do my editing when I type up my jottings onto my laptop, then I print the whole thing out (only when the whole thing has been typed up) and mark-up the manuscript traditionally whilst re-reading. Then I go back to the laptop and collate all my further corrections. I may tinker with it a while longer after all this is done, but at that stage most of my writing is ready to be sent to a proper editor. I believe in editing. I enjoy cutting whole sections out and paring things down to a base level. I wrote The Canal exactly like this, following certain themes I’d written down in other cheap notebooks along the way. I try to keep the writing process as simple as possible.

The dialogue here is ridiculously beautiful. I kept thinking about Harold Pinter. Do you have any interest in writing a play?

I would like to write a play. And I love writing dialogue. I feel quite unrestricted when writing dialogue. I once wrote a film script with a good friend many years ago, but we never finished it – which was a shame. Although, my hero is Samuel Beckett and no one has beaten him since (Pinter got close), so this fear and respect normally deters me from trying.

The book also reminded me a little of Marina Abramovic’s The Artist is Present. There is something inherently powerful in two people sitting with each other and doing nothing and having no agenda. I wonder if meditation or meditative activities influenced you at all, or if the setting of the novel arose from the characters.

I really wanted to see that exhibition. Hari Kunzru and Tao Lin both wrote about it recently. That exhibition is clever because it at once repels and draws people closer. I like that a lot. The idea of two people sitting on a bench thrills me; anything can happen (although 9 times out of 10 nothing happens – which is just as thrilling for me). I am not interested in things like characterisation or plot, but I am interested in two character types: those who accept boredom and those who try to fight it. I like the idea that a certain friction is caused when I write about these two types – the meditation for me is the result of this friction and nothing else. In the fiction (and friction) of The Canal, both characters try to create their own realities. For me, everything is fiction and construct, even realism (I blame Derrida), so I like to construct a scenario based on this falsehood. For me the unending symbol in The Canal is the perpetual motion of a pendulum, a constant act of vacillation: things go one way and then pass by in the other direction, and I enjoy this tussle. The narrator of The Canal walks to the bench one day out of boredom, he begins to create a reality from the things he sees passing him by all day long: the pedestrians and cyclists on the towpath, the coots and the moorhens on the canal, et cetera, and behind all that the office workers busying themselves in the whitewashed office block. Then she suddenly turns up and begins to pull him away from all that, into her own reality, the metronomic motion which then commences between the man and the woman mirrors everything else within and outside the book – including the thematic tug of war between the construct of fiction and the falsehood of realism. For me nothing and everything is real in The Canal, and the only way I could mediate this was between the nothingness that separates two strangers on a sitting bench.

Here’s an excerpt from early in the story, one of the many characters the narrator encounters/observes from the bench:

She fell into silence as a woman walking a pet Staffordshire Bull Terrier ambled by the bench. The dog happily sniffing along. I watched the dog; it looked so happy. It actually looked like it had a smile on its face; sniffing around at stuff, litter, rubbish, and scraps of things, running from one bench to another, catching the scent left behind from other dogs—coded messages that were invisible to us humans.

The owner looked to be in her mid-twenties. I don’t know, though, she could have been younger. It was hard to tell. She was wearing sports gear—white Reebok trainers, grey jogging bottoms, a navy blue hooded top—as well as gold earrings and bracelets. Her clothes were too tight for her bulging arse and torso; her gut lolloped about. She had dyed blond hair, the roots dark; it was scraped back to such an alarming extent that she looked startled. Her face was heavily made-up. Her large earrings dangled, respondent to each of her aggressive movements. She was screaming at the dog.

“Come here you little cunt. Come here. Don’t go near those people. Come here you little cunt. Come here. Watch those fucking people. Come here you little cunt. Come here. Don’t go too far. Come here. Come here you little cunt. Don’t go near those two people. Cunt. Come here you little cunt. Come here. Cunt. Come here you little cunt. Don’t go near them. Come here.”

The dog wandered over to me. It was a beautiful dog. Sandy brown. A bitch. She looked up at me and I petted her head and around her thick, muscular neck. She jumped up playfully and tried to lick my face.

“Come here you little cunt. Don’t try to attack the man. Come here you little cunt. Come here. Leave the man alone. You little cunt. Leave the man alone. Come here.”

I looked up. “Really, it’s no problem . . . She’s a lovely . . .”

The dog ran back to her. She kicked the dog in the ribcage. The dog yelped so loud it caused some coots to scatter across the murky water.

“That’ll teach you to come here you little cunt.”

Tags: lee rourke, The Canal

awesome.

awesome.

NIce interview.

NIce interview.

How can boredom be embraced? I don’t understand. How can you ‘do nothing’? Wouldn’t ‘doing nothing’ be the very definition of passive nihilism? Cool interview this.

Hi Stefan,

First, happy you liked the interview.

Well, I think we should all try to embrace boredom. By this I mean accept it by not doing something to help keep the weight of boredom at bay. Of course, as The Canal demonstrates, it is mostly a losing battle . . . but, I guess, it’s fun trying.

I think the passive nihilism that Simon Critchley speaks of is not really the act of doing nothing (I mean, I agree, doing ‘nothing’ is doing something, even if that ‘something’ is nothing), it’s more the conscious choice to fill the gaping void of existence with things that help pass the time (Nietzsche called it Schopenhauerian pessimism, I think): non aggressive/spiritual things like meditation and yogic retreats, or strange things like astrology, tarot and psychic readings. Which are, by and large, utterly pointless. Critchley put out a great book some time ago called ‘Very Little . . . Almost Nothing: Death, Philosophy, Literature’ that I think everyone who hasn’t yet read it should do so, in which he describes passive nihilism as a form of ‘don’t worry, be happy’ existence: where there is felt a sense of life’s absurdity by an idividual, but s/he carries on anyway, finding new and quirky ways to ease the pain. For me, this is the losing battle, nothing we have created for ourselves (and by this I’m thinking of things like God, technology, recreational drugs, et cetera) help us to shift the weight of boredom. It is always there, underpinning everything.

So, I guess for me at least, in the act of embracing boredom (something that could end up in catastrophe or nothing in particular) we are at least confronting existence – looking at it head on, so to speak. Which is better that letting time pass us by in a shower of ‘nice’ things.

Lee.

Thank you for this generous reply, Lee.

I’m still a little confused. When you describe boredom as ‘underpinning everything’ isn’t that just what the ‘gaping void’ does? Isn’t awareness of the gaping void anxiety/angst? not boredom?

i am really excited to read ‘the canal’ – great interview, guys.

The dialogue in the second excerpt floored me. Looking forward to reading the book.

How can boredom be embraced? I don’t understand. How can you ‘do nothing’? Wouldn’t ‘doing nothing’ be the very definition of passive nihilism? Cool interview this.

Hi Stefan,

First, happy you liked the interview.

Well, I think we should all try to embrace boredom. By this I mean accept it by not doing something to help keep the weight of boredom at bay. Of course, as The Canal demonstrates, it is mostly a losing battle . . . but, I guess, it’s fun trying.

I think the passive nihilism that Simon Critchley speaks of is not really the act of doing nothing (I mean, I agree, doing ‘nothing’ is doing something, even if that ‘something’ is nothing), it’s more the conscious choice to fill the gaping void of existence with things that help pass the time (Nietzsche called it Schopenhauerian pessimism, I think): non aggressive/spiritual things like meditation and yogic retreats, or strange things like astrology, tarot and psychic readings. Which are, by and large, utterly pointless. Critchley put out a great book some time ago called ‘Very Little . . . Almost Nothing: Death, Philosophy, Literature’ that I think everyone who hasn’t yet read it should do so, in which he describes passive nihilism as a form of ‘don’t worry, be happy’ existence: where there is felt a sense of life’s absurdity by an idividual, but s/he carries on anyway, finding new and quirky ways to ease the pain. For me, this is the losing battle, nothing we have created for ourselves (and by this I’m thinking of things like God, technology, recreational drugs, et cetera) help us to shift the weight of boredom. It is always there, underpinning everything.

So, I guess for me at least, in the act of embracing boredom (something that could end up in catastrophe or nothing in particular) we are at least confronting existence – looking at it head on, so to speak. Which is better that letting time pass us by in a shower of ‘nice’ things.

Lee.

Thank you for this generous reply, Lee.

I’m still a little confused. When you describe boredom as ‘underpinning everything’ isn’t that just what the ‘gaping void’ does? Isn’t awareness of the gaping void anxiety/angst? not boredom?

i am really excited to read ‘the canal’ – great interview, guys.

The dialogue in the second excerpt floored me. Looking forward to reading the book.

Stefan,

‘Isn’t awareness of the gaping void anxiety/angst? not boredom’

We’re treading into Heideggerian territory here – something I don’t mind doing. Heidegger’s ‘Angst’ is translated as ‘dread’ in English, which is a different thing to boredom. Although, he did link the two in his 1929 lecture ‘What is Metaphysics?’ where he proclaimed that we are ‘suspended in dread’ and caught in the ‘muffing fog’ of boredom. For Heidegger this is a good thing, as it gives us perspective on the gaping void (abgrund). A foothold where we can rebuild things. It’s a big ask.

For me though, boredom is a tangible physical and mental feeling, a kind of slow misery or dread, where time (as we recognise it) becomes an obstacle to be overcome. Boredom is our inability to deal with this suspension coupled with the inner realisation of the gaping void boring into us.

But this is just my personal feelings on boredom – I am sure they are different for everyone. All this is why I tackle boredom as an unanswered philosophical question in my fiction. Any other way is a complete head fuck for me.

Best, Lee.

Stefan,

‘Isn’t awareness of the gaping void anxiety/angst? not boredom’

We’re treading into Heideggerian territory here – something I don’t mind doing. Heidegger’s ‘Angst’ is translated as ‘dread’ in English, which is a different thing to boredom. Although, he did link the two in his 1929 lecture ‘What is Metaphysics?’ where he proclaimed that we are ‘suspended in dread’ and caught in the ‘muffing fog’ of boredom. For Heidegger this is a good thing, as it gives us perspective on the gaping void (abgrund). A foothold where we can rebuild things. It’s a big ask.

For me though, boredom is a tangible physical and mental feeling, a kind of slow misery or dread, where time (as we recognise it) becomes an obstacle to be overcome. Boredom is our inability to deal with this suspension coupled with the inner realisation of the gaping void boring into us.

But this is just my personal feelings on boredom – I am sure they are different for everyone. All this is why I tackle boredom as an unanswered philosophical question in my fiction. Any other way is a complete head fuck for me.

Best, Lee.

Great interview and looking forward to The Canal!!!

On the subject of boredom, I wonder whether boredom WAS embraced, possibly almost obsessively, around the beginning of the 2000s…during and a couple of years before and after the millennium hype time there seemed to be some quite aggressive collective cultural preferences for the minimalist, and attitudes that seemed to imply that any kind of distraction technique or ‘set dressing’ in music, writing, art, furniture, personal appearance etc. were just a bit pathetic really. (Just talking about middle-range UK culture here.) Almost like the desperation for a content, or context, for the end of a pretty brutal century and the start of an unpredictable one had played its part of distracting people from the much scarier fact of the arbitrariness of it all, had been done to death, worn out, and proved wrong when no planes actually fell out of the sky etc. A similar thing is supposed to have happened around the year 1000 when the Anglo Saxons who’d gone over to Christianity got scared shitless of the second coming and end of the world, but then felt jipped when nothing happened. I think a bit of the embrasure of boredom as minimalism lives on in our popular culture of the early whatever-this-decade-is, but less is no longer always necessarily more. I think I’m for embracing boredom/the void under this interpretation, but the wild eyed craze for less is more pissed me off at the time of the millennium and continues to niggle me a bit when the residue of it manifests as minimalist strimming for its own sake. If that makes any sense!

Great interview and looking forward to The Canal!!!

On the subject of boredom, I wonder whether boredom WAS embraced, possibly almost obsessively, around the beginning of the 2000s…during and a couple of years before and after the millennium hype time there seemed to be some quite aggressive collective cultural preferences for the minimalist, and attitudes that seemed to imply that any kind of distraction technique or ‘set dressing’ in music, writing, art, furniture, personal appearance etc. were just a bit pathetic really. (Just talking about middle-range UK culture here.) Almost like the desperation for a content, or context, for the end of a pretty brutal century and the start of an unpredictable one had played its part of distracting people from the much scarier fact of the arbitrariness of it all, had been done to death, worn out, and proved wrong when no planes actually fell out of the sky etc. A similar thing is supposed to have happened around the year 1000 when the Anglo Saxons who’d gone over to Christianity got scared shitless of the second coming and end of the world, but then felt jipped when nothing happened. I think a bit of the embrasure of boredom as minimalism lives on in our popular culture of the early whatever-this-decade-is, but less is no longer always necessarily more. I think I’m for embracing boredom/the void under this interpretation, but the wild eyed craze for less is more pissed me off at the time of the millennium and continues to niggle me a bit when the residue of it manifests as minimalist strimming for its own sake. If that makes any sense!

[…] Novel, The Canal Posted in Books, Literature, Writers by Biblioklept on June 26, 2010 At HTMLGIANT, Catherine Lacey interviews Lee Rourke about boredom, the writing process, dialogue, foxes, and his new novel The Canal. Read our review […]

[…] the author's website the author's blog the author's Wikipedia entry excerpt from the book […]

[…] page of The Canal at ‘other’ magazine. Catherine Lacey interviewed him for us here. Tags: 3:am, lee rourke, melville house, The […]

I read the interview to get out of boredom. It’s refreshing.

I read the interview to get out of boredom. It’s refreshing.

[…] μπλογκ του συγγραφέα, μια συνέντευξή του με δύο αποσπάσματα από το βιβλίο και μια […]

mr rourke

just checkin your still alive

you misrable owd git

matt lamb