Skinned: An Interview With Antjie Krog

*****

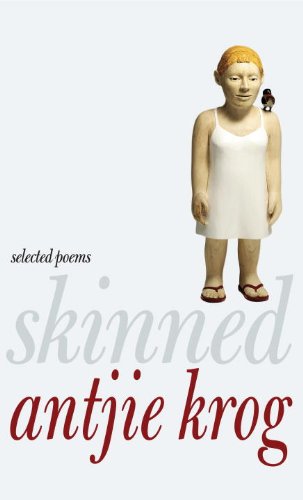

One of South Africa’s foremost contemporary poets, Antjie Krog has been described as the “Pablo Neruda of Afrikaans.” I stumbled on Antjie Krog’s work several years ago and was rewarded with the strange, passionate, tough and well-organized verses of Body Bereft (which contains, among other work, her strange and fiery Menopausal Sonnets). So, I was excited when, earlier this year, a Selected poems of Antjie Krog, Skinned, released from Seven Stories Press.

*****

And here, then, is the transcript of an email interview I did with South African poet Antjie Krog that touches on those Menopausal Sonnets, South African Politics, Afrikaans, Indigenous Literature Translations, etc, etc:

*****

Rauan: Many of the readers of this blog will be drawn to “Menopausal Sonnets” and other examples of frank, fiery and often crude writings about the changing (and failing) female body. In your Author’s Note you mention that “Skinned” contains “traces” of certain foreign writers, including Sharon Olds and Carolyn Forché. And it seems to me, besides, that you are naturally a fiery, direct and spicy personality. (How right and/or wrong am I?)

And can you elaborate on what, inside and outside, brought you to write such direct and sometimes graphic poems containing bits like

…you grab this death like a runt and plough its nose

right through your fleeced and drybaked cunt.

and

……the waist thickens and

the vagina wall thins and the colon crashes

through its own arse. how dare her toe

nails grow so riotous then…

Antjie: Poetry has taught me how to live. Everything of value I have found there. For me it therefore ought to be able to encompass one’s whole life. I am very aware what male poets have decided the Main Themes of Literature should be: Love, Death, God, Nature and War. This is fine, but it should also say menstruation, menopause and grandmother, also politics. And it is here that I found the two poets you mention invaluable – Olds gave me language for the body, Forché language for politics which drew on the personal.

At the same time poetry should always take risks. Writing a poem should be like jumping down a waterfall – you don’t know whether you will be crushed below or swim away with exhilaration. The risk taken in these poems is sometimes great: whether it is by doing a praise poem for Desmond Tutu in the form and phrase of indigenous languages without sounding sycophantic, or in writing about the menopausal vagina without being so banal that the fury gets lost.

RK: One of the many and intertwining selves in “Skinned” is that of a complicated National South African voice. And I say “complicated,” of course, because, well, it’s always complicated but, also because you were born into an Afrikaaner family in a rural part of the Orange Free State (where, fyi, my family would often go to on weekends and stay on a farm, near Heilbron, with one of my dad’s greyhound racing friends).

But at the age of seventeen (1969?), as the Publisher’s note indicates, your poetry attracted local and national attention for its sexual and political nature:

“look, I build myself a land

where skin colour doesn’t count

only the inner brand of selfwhere black and white hand in hand

can bring peace and love

in my beautiful land”

— from “My Beautiful Land”

And the Publisher’s Note goes on to say that

“When the first political prisoners were released from Robben Island, Ahmed Kathrada read this poem to an audience of thousands at a mass rally in Soweto, mentioning the hope that the words had instilled among those held captive on the island: ‘If a school child was saying this, we knew we would be free in our lifetime.’ ”

Can you tell us a bit about growing up Afrikaans in an Apartheid-entrenched South, and the pressures, good and bad, that this (and the subsequent transition of power) brought to bear on you and your poetry?

AK: To grow up as an Afrikaner child in South Africa during the sixties was to live in a complete and completed world. This was how natural and obviously right one’s position felt. One woke up with Afrikaans in the house, and on the radio, what was written on jam and cereal boxes, was all Afrikaans, and in the bus, at school, everybody spoke Afrikaans. The rivers we crossed, the farms we passed, the hills we surveyed, the towns we came from, the songs we sang, all had names from our language. This language was busy producing a literature that delivered writers of international stature like Andre P. Brink and Breyten Breytenbach, but more importantly, it was also the language of the top leadership of the land. The president, the cabinet spoke your language. As we traveled on holidays my father would point out the mountains and plains where events took place in which Afrikaners died fighting the British, fighting the Zulu – so the country felt marked and paid for by us. So my society was a confident one, it felt in total control during the sixties under the leadership of Verwoerd and Vorster. Although things began to unravel fast in the seventies, it was precisely this confidence and the top quality literature which enabled me to write what I wanted, causing a scandal, but NO censorship.

The pressures I was aware of existed in myself: how does one make sense of what one more and more begin to see as a deeply unjust society? Then: how does one formulate it? The hardest part came later: one can SAY that one is against apartheid, but how do you LIVE against apartheid? In my non-fiction book ‘A Change of Tongue’ I compare the sixties with the society just after Nelson Mandela became president and how Afrikaners slowly had to learn ‘a change of tongue’.

RK: I’m very impressed with how well organized and determined “Skinned,” a Selected volume, presents itself, divided, as you say in the Author’s note, by “theme,” into 5 sections where poems spanning several decades intermix, creating a “kaleidoscope” view/portrait of “Antjie Krog” as woman (lover, wife, mother, ageing female, feminist), South African (Afrikaaner born), translator, collaborator, National Voice and, above all, as emphasized by the 1st poem in the collection, an artist of language, a “poet.” I’m guessing, then, that you must have to make some painful cuts, that some really strong and favorite poems must have fell to the wayside?

Can you, then, tell us a bit more about the putting together of “Skinned” which is, after all, your first book of English language poetry published outside of South Africa?

AK: This volume was very much influenced by Dan Simon, the publisher, and someone who knows South Africa very well. Working with him I felt that he not only knew my work, but also knew exactly what it was that he wanted to introduce to an outside readership. If we could just take one step back: over the years I had three steep learning curves: covering the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, translating poems from nine of South Africa’s indigenous languages into Afrikaans and immersing myself in African philosophy to begin to grasp what was really happening in my country. Technically these things happened ‘outside’ the ten volumes that I was publishing. Dan Simon wanted that to be part of ‘Skinned’ and so a much richer, more deeply rooted content emerged.

The regrets I have are that the full contexts of the volumes have evaporated. Every volume of mine has a title that is not only thematically important, but also stylistically and hermeneutically relevant. A volume would be layered first with a historical reference which would flash the philosophical argument, then the poems would refract the title in many layers of meanings which would then deeply influence the style of volume, its punctuation, its rhythm, its rhyme and finally its meaning. Every poem would speak with the full force of the volume. ALL of this had fallen away as the poems were removed from their contexts and had to come to some new coherency. This means that a poem which was crucial for the initial volume had to give up its space to another poem crucial for the new context. Even smaller parts had to be removed as it only made sense within the broader context (listen to the podcast with Peter McDonald from Oxford University)

And then I haven’t begun to talk about what had been lost in the translation!!

RK: In addition to making the original versions of these poems in Afrikaans, your native tongue, you also translated most of them into English yourself. In the “Acknowledgements” section of “Body Bereft” (which released in 2006 ), you wrote that in some cases the “translation process required creative solutions, which in their turn opened up other possibilities in the poems.” Can you give us a sense of what’s it like to wear the two caps of original author and translator? And could you give us details of a particularly memorable example (or two!) of a “creative solution” and the possibilities this led to?

AK: I recently attended a very interesting conference on writers who translated themselves (Brodsky, Beckett, Arendt, etc) and the problems were multi-full but also obvious. The writer’s effort goes into the heart/essence of the poem, the translator’s into trying to capture that heart in the new language. As a writer one often doesn’t have the patience or skill for the capturing process and sometimes prefers to write a new heart in the new language.

Another factor is that when somebody else translates me I often find the work feels too English. When I translate, I try to stay within the Afrikaans rhythm. The work must maintain its from-elsewhere-ness. Then there is also the truth that I know what a cliche is in Afrikaans; I don’t necessarily in English, so the poet as translator can often translate his work in a way which sounds old-fashioned in the new language.

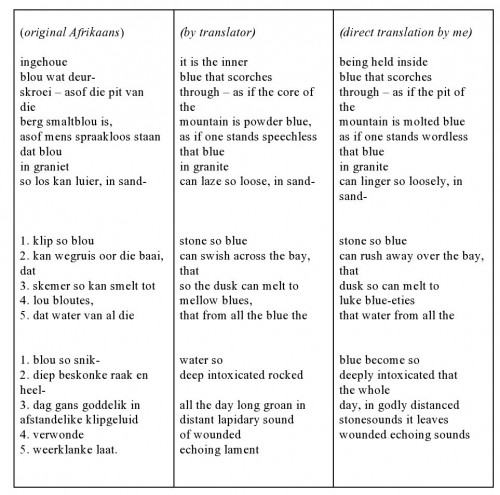

Lastly, some things that are beautiful in one’s language do not work in another, unless distorted. In the jpeg below you will see an example of an Afrikaans poem, then the translation by a good translator and then my own literal translation trying to capture the full nuance of the Afrikaans, but the end result is un-English.

RK: “Colour Never Comes Alone” (Skinned’s 3rd section) is comprised of translations of indigenous African language poetry—”extracts from several speakers who lived in the land long before (Europeans) arrived.” Can you tell us more about the experience, what it was like, what you learned—some sense of the different voices, image-systems, senses of self, land, etc, that you found yourself immersed in??

AK: In the first place I was elated to find the excellent quality that I suspected I would find was, as it turned out, there in great abundance. It took a lot of hard and risky work to have it crystallized, because to find a group of translators who have among them enough knowledge of the original language AND of the target language to do justice to the work was not easy. One also has to bear in mind that African languages communicate on a literal and figurative level. This outstanding metaphorical quality of the African languages had been underlined in the nineteenth century already by French missionary, Eugene Casalis:

‘The language (Sesotho), from its energetic precision, is admirably adapted to the sententious style, and the element of metaphor has entered so abundantly into its composition, that one can hardly speak it without unconsciously acquiring the habit of expressing one’s thoughts in a figurative manner.’ ([1861] 1965,307)

In Xhosa the most often quoted example is of course the Xhosa name of Nelson Mandela: Rholihlahla = pulled branch (literal), troublemaker (figurative).

The challenge therefore was to find somebody who can convey both the literal and the figurative meaning. Here is an example translated by the Xhosa poet himself:

I ask you to be quiet,

for the imbongi from Xhalanga to speak.

Let the weak ones be quiet

I am speaking of important matters.

I shall show the lies in good Xhosa

The liars will be shaking,

I will talk clearly in opposition.

Iimbongi, lend me two opportunities

I will use them both.

Young men lend me two opportunities

I will use them inside as well as outside.

Young men, lend me two opportunities

I will use them to look after the aged.

Young men, lend me two opportunities.

I will use them both to protect us.

Young men, lend me two opportunities.

I will respect the elders and be brave.

An old retired minister, Koos Oosthuyzen, who grew up in the Eastern

Cape, speaks classic Xhosa and is intimately familiar with rural customs and

culture. Being a minister himself, his Afrikaans is also classically elegant. He

made the following translation:

Silence please, for the imbongi of Vulture hill is bellowing.

Those who trudge along like wasted livestock

will be speechless for a change

because I am going to say things that weigh heavily

I am going to say them in deep Xhosa from Xhosaland

My words will let some people fall about frightened like liars,

They will jump around like rattling red rhebuck in a rapid wind.

I will sing clear and solid like a songbird on a stony mountain.

Iimbongi, lend me two bush tiger capes

With one I shall gird myself and with the other sweep the way clear.

Boys, lend me two fighting sticks.

The one I will take to meetings

and with the other one hack away weed.

Initiates, lend me two curved hilt knives.

With the one I will slaughter for the ancestors

and with the other cut strips for the grey headed.

Men, lend me two wild olive tree staffs.

With one I will tame animals and with the other chase the thunder away.

Young men, lend me two dancing canes.

One I will give to the cranefeather heads

and with the other loudly beat my shield.

Once I was familiar with the mechanics, conventions and linguistics of the traditional Xhosa praise song, and having been asked to write something for the occasion of his eightieth birthday, I made a praise song for Archbishop Tutu which follows all the rules for a praise song: it first asks who shall do the praising, because the time is ripe. Then the Singer introduces (usually) himself to make his credentials clear for taking on the task. Then the text must focus on the physical as well as spiritual part of the object of praise, it must bring in wordplay, idioms, as well as make combos of the objects’ characteristics – one word which capsulates many and in the end defines the essence of the person( e.g. he who-always-says-the-unheard-of-never-said-before-things.) It also ends in a typical way: I can go on and on, but like a shooting star stops here. The last two words ndee gram! form what is called an ideophone signaling that the imbongi has finished the contribution.

RK: Very interesting, Antjie, to see just how different those versions of the Xhosa praise song are! And I’d like to conclude this interview by asking you how you feel about where your country is now? And where do you think it’s headed (challenges, possibilities, hope, etc)? Obviously, South Africa is quite a different place, all in all, than the South Africa you grew up and began writing in during the sixties (and in many ways, of course, it is a much better place) but I’d like to quote Nadine Gordimer where she says in a 2012 Foreword to a new edition of Mbuyiseni Oswald Mtshali’s “Sounds of a Cowhide Drum” (originally published in 1971) that “the world you will enter through these poems is a black man’s world made by white men,” and, sadly, in spite of all that’s transpired in the intervening decades, that “the daily circumstances of his life remain those of the majority population of South Africa.”

AK: I am in two minds, always. Part of me understands why things are so out of hand, is even surprised that things go so well taking into account the systematic deprivation of education and schooling and the generations of humiliated and scorned senses of self. At other times I think: this government cannot deliver what is necessary and it will have to, at some stage, say: we WANT to give you a better life, but these whites are in the way. (In a strange way that would be preferable to the current frozen situation – it would be truly a privilege to leave knowing that people’s lives would genuinely change for the better – but that is not what we saw north of us!) And then of course one can’t help remembering another group who said that they were German, they felt and behaved as Germans, but one day those who regarded themselves as the gatekeepers of what is German decided: you are not. But in essence: it becomes more and more impossible for me to live an honourable life in a country where poverty knocks on your door so many times a day that you stop hearing the poor. I find that unacceptable and therefore wish, at times, that the suffering of people would knock on other doors of other poets in other countries first.

*****

Antjie Krog was born in 1952 in the Free State Province in South Africa. In 1993 she became editor of a progressive Afrikaans language monthly in Cape Town and later worked as a radio journalist covering the Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings in the late ’90s, all the while writing extensively for newspapers and journals. She and her radio colleagues received the SABC Pringle Award for excellence in journalism for their coverage of the commission hearings. She has won major awards in almost all the genres and media in which she has worked: poetry, journalism, fiction, and translation. Krog’s first volume of poetry was published when she was seventeen years old and she has since released thirteen volumes of poetry, receiving nearly every literary award available for works in Afrikaans. She is married to architect John Samuel, and is the mother of four children.

*****

Tags: Afrikaans, Antjie Krog

Rauan is my fave. ;-)

The clinging to privilege, even by well-intentioned people, people who reject political impositions of racial hierarchy, is impossibly tough. How many will yield ‘their’ places–especially in favor of nothing better and, maybe, something worse for the newly advantaged?

But one would also ask, how is Afrikaans not an indigenous “African” language?

(Subtle interview; Krog is a strong find for us less informed.)

Afrikaans— hmmmm… well, it’s pretty much Dutch, somewhat morphed and evolved thousands of miles away from home.

———————————

is what we speak in the U.S. an indigenous “American” language?

is Spanish on this side of the pond a group of indigenous “American” languages?

but, i hear ya :)

(and, yeah, that’s a tough one about clinging to privilege. as you say, “impossibly tough”)

[…] so, let’s revisit an interview that I recently did with South African poet Antjie Krog which ended with me asking Antjie “how […]

[…] Complete article: HTML Giant […]

[…] http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/antje-krog http://htmlgiant.com/author-spotlight/skinned-an-interview-with-antjie-krog http://www.thewhitereview.org/poetry/three-new-poems […]