25 Points: EarthBound by Ken Baumann

Earthbound

Earthbound

by Ken Baumann, Foreword by Marcus Lindblom

Boss Fight Books, 2014

191 pages / $14.95 Buy from Boss Fight Books

1. This past December found me at several Christmas parties and office get-togethers (mostly with my wife’s coworkers and friends). Because I’m kind of self-absorbed and, even if I wasn’t, I’ve been spending the past five months with my newborn son, I don’t have much to contribute by way of conversation, so I turned to talking about Earthbound.

2. My parents never bought me a Super Nintendo or any of the other 90’s child indulgences (although I was a member of the Burger King Kid’s Club and was allowed to watch hour upon hour of Nickelodeon), so I had no point of reference for the cult-hit video game.

3. I had trouble finding anyone who knew what I was talking about. They had never heard of the game, and cared even less about Ken Baumann’s book.

4. The few times that I actually found someone who played Earthbound our conversations were hauntingly simple.

5. Me: Have you ever played Earthbound?

Partygoer: You need to go home tonight and play it right now. [End of conversation.]

6. I never got around to it. Blah-blah work. Blah-blah new parent. Blah-blah smartphone.

7. But the real reason why I didn’t play it was because of how purely pleasurable Baumann’s book is.

8. Ken Baumann’s Earthbound is a charming intermingling of videogame history, walkthrough, memoir, and philosophy. He serves as Virgil to the reader’s Dante as he guides us through the “total inverse of Dante’s Hell” that is Twoson, Threed, Summers, and the other locales of the game while drawing on everything from Straw Dogs and Jung to Gak’s role in 90’s gross-out culture and House.

9. Baumann depicts the “irretrievable beauty in video games…” as a Romantic would depict vernal wood. As sacred: “Ephemeral glitches that point to the sublime. Randomized variables that are made more poetic in their expression by their adjacency to the rote and the banal.”

10. The strongest of Baumann’s threads are the biographical ones. Earthbound [the book] is a study of how Earthbound [the game] impacts lives, especially the lives of little Kenny in Texas, his estranged brother Scott, and the support of Ms. Baumann, and the loving Aviva. READ MORE >

January 23rd, 2014 / 4:43 pm

25 Points: The Circle

The Circle

The Circle

by Dave Eggers

Knopf, 2013

504 pages / $27.95 buy from Powell’s or Amazon

1. Nothing about The Circle is very surprising or new. Big Brother is a clichéd, outdated reality show. The privacy vs. transparency debate is as ubiquitous as the scope it describes. It’s obvious from page one which side the novel will end up on.

2. I don’t care about any of this. The transparency-obsessed campus of The Circle (a proxy for Google) is not an unappealing environment to me. Most of the time, it’s ridiculously attractive.

3. The relentless lists of online activities that the protagonist, Mae, conducts daily are not the downward spirals of doom they should be. Instead, the repetitive passages feel hypnotic and pleasurable and I live vicariously through Mae’s Internet high. I should read her decline into web addiction and over-sharing critically, but instead I feel the same breathless, click-through-again compulsiveness that I do staying up too late online, browsing websites and managing my own social media accounts.

4. I can’t figure out if I’m the exact target audience for The Circle, or the exact opposite of it. Are its warnings meant for those younger than me who’ve never known a world without Google? Or those older, who take a certain pride in refusing to get an Internet connection or email account?

5. The novel circles around the same few themes, visits the same few locations, and its protagonist, Mae, repeats the same tasks over and over again. This repetition gives me an intense, almost physical pleasure: a caffeine-like tightness in my brain, behind my ears; a lifting in my chest; the impulse the read as quickly as possible.

6. It’s more engaging to read about what Mae does on her computer than about her interactions with human characters, who are consistently flat—placeholders for perspectives.

7. Internet Rorschach: is this passage a dark chute of terror or an energizing, endorphin-generating endurance run? “[Mae] embarked on a flurry of activity, sending 4 zings and 32 comments and 88 smiles. In an hour, her PartiRank rose to 7,288. Breaking 7,000 was more difficult, but by 8, after joining and posting in 11 discussion groups, sending another 12 zings, one of them rated in the top 5,000 globally for that hour, and signing up for 67 more feeds, she’d done it. She was at 6,872, and she turned to her InnerCircle social feed. She was a few hundred posts behind, and she made her way through, replying to 70 or so messages, RSVPing to 11 events on campus, signing nine petitions and providing comments and constructive criticism on four products currently in beta. By 10:16, her rank was 5,342, and again, the plateau — this time at 5,000 — was hard to overcome. She wrote a series of zings about a new Circle service, allowing account holders to know whenever their name was mentioned in any messages sent from anyone else, and one of the zings, her seventh on the subject, caught fire and was rezinged 2,904 times, and this brought her PartiRank up to 3,887.” The passage continues for several more pages.

8. Fiction Writing 101: A complex character should always want something. For effective character development, ask: what does the character want? Mae wants a job at The Circle, and she gets it on page one. Her character is empty, simplistic, a shell.

9. Perhaps stripping Mae of any real wanting is the novel’s innovation: what happens when we want for nothing? Are we human anymore, or just shells of ourselves?

10. Something Mae sort of wants is a good rating of her work at The Circle (99% or higher for every inquiry she answers, which number in the hundreds each day). But this obsession with approval and high ratings doesn’t quite ring true to me: with quantity comes ambivalence, not a desire for quality. When reviews are always perfect, they have no meaning. READ MORE >

January 16th, 2014 / 4:38 pm

Prompted by Lily Hoang’s ‘On the Limits of Empathy, or, the Universality of Grief’

What struck me immediately after my dad died is that the grief I felt seemed simultaneously the most and the least unique feeling in the world: in its singularity no one could understand it; yet in its universality, to some extent, everyone could. I was comforted by this; by this sense that millions and millions of people have been in this situation and got through it. Time rolls on.

I find it interesting that in the therapy I’ve had since he died uniqueness and originality are subjects I’ve returned to again and again. Primarily, it has to be said, I’ve spoken about these subjects in terms of disappointment at realising that aspects of my personality I’d always thought were just completely my own are not really, after all, so unique. I don’t know what it might mean; perhaps it’s some sort of accounting I’m carrying out: what’s me; what was him etc? Perhaps, as well, I may just have sublimated the wanting of an original grief; that desire then emerging in another form? I find a possibility of truth in that. I realise I have a problem with grief: I feel guilty about indulging it. My dad dying was the terrible thing and that anything else might come close to causing me an equivalent level of pain – I mean even my grief over him dying – feels like something awfully hard to accept.

Last Thursday it was exactly four months since he died. I went to work; I sat at my desk; I talked to my colleagues; and I checked Facebook and my Gmail. I left at half five for an appointment with my therapist. The beginning of the week I’d felt very focussed on the coming Thursday; I’d expected it to be a tough day. As it turned out, for the biggest part of the day, it wasn’t tough at all. After seeing my therapist though things seemed totally to fall apart. I don’t know how to describe what happened other than to refer to those times a person feels hyper: a lot of energy; and, I guess, a kind of excitement at the things you might be able to do whilst in this mood; with it only slowly dawning on you that this excitement is a waste of time as this energy is directionless and impossible to focus. Well I had kind of the opposite of all that. There seemed to be a hyper-ness about how I felt, sure; yet instead of excitement featuring it absolutely was a down mood. And even now, two days later, I still don’t feel certain what happened: either I’d accessed something I’d tried to deny or I’d given one thing the name of something else out of a sense of dutifulness or, perhaps, a mixture of the two.

I wanted to tell my friend on Thursday about the significance of the day. I didn’t though. I wanted to tell it just as news but I was concerned, rather, it might come out as some kind of plea for sympathy. I’m not in a position yet to be able to assess the rights and wrongs of this.

This time last year I was involved in a brief relationship with a woman I’d met, in all places, via Facebook Scrabble games. I’d been playing online Scrabble for months – not in the hope of meeting anyone; just because I liked Scrabble – and opponents always seemed to be from London or Australia or somewhere; anyway, places very far away from where I live; this woman was from Stockport – just round the corner, effectively. Anyway, her dad had died some years earlier and she missed him very much; and she got it into her head that she wanted to meet my dad. As time passed this seemed to become more and more of a preoccupation for her; yet, it began to seem to me, more a kind of theoretical preoccupation than an actual one. What I mean is she liked to discuss meeting my dad yet never wanted to make any actual plans to that end. So the meeting never happened. She would always ask though, often even before she’d asked how I was, if my dad was okay. Since he died I’ve wondered on several occasions if I should get back in touch with this woman to let her know about my dad. I haven’t though. I think the occasions when I do consider this are times when I very much do want sympathy – and not necessarily perhaps for reasons connected to my dad. To use his death then as a means of acquiring that sympathy would feel very wrong to me.

Empathy is possible, absolutely. Regarding this idea of ‘genuine empathy’, well, if ‘genuine empathy’ is only possible between like and like I reckon it’s an idea that’s better off ditched. A person can understand and share another person’s feelings, sure; of course though they can’t access those same feelings in their particularity and uniqueness. Over these past four months I’ve been hugely grateful for the support of family and friends.

Since he died I have cried loads. The most recent time being last night at the thought of sorting through his clothes which I knew I’d be doing today. So far I haven’t cried today.

Tonight I will drink two cans of lager. Two because it’s that there are only two in the fridge. In the days and weeks following his death I drank loads and I drank all manner of stuff. The main reason for my drinking was, I think, because I just didn’t want to be at home – the home I’d lived in all my life with my dad. Drinking took me to the pub. It put me amongst people – alright, most of the time not people I was talking to (generally I’d be in the pub alone with just a book for company); it made that period between getting into bed and falling asleep last probably just minutes; drinking had a lot going for it. Today, mentioning to my aunt about the two cans I’d had last night as well, I realised something had changed: recently I’ve been drinking less.

About a month after my dad died the mothers of two friends at work died. Then the month after that the mother of a third friend died as well. I don’t think there were sky high expectations of me being able to prove particularly empathetic given what I was going through myself; and that was perhaps fortunate for me. Mike said to me though that people he would have expected a lot from at that time had, he felt, let him down; whereas people he didn’t expect so much from had really delivered. The reason for me saying this – I assume it’s clear – is that he felt I’d delivered. He meant, I think, I’d said stuff to him which was appropriate and which was useful. I’d found that easy to do though. As I said to him, perhaps I knew what to say because I’d so recently gone through this stuff myself. And that easiness is something I just don’t trust. It feels like due to it being so easy for me to know what to say what I said can’t have meant too much. Really, I mean, how useful are words? And I feel my sense of their uselessness takes something away from them even as I’m saying them. Still though, at such times words are often all we have to give.

How do we learn about death? We can learn about it from books, sure; but from books we’ll only take the generalities. Death in its horrible particularity is something we can only begin to learn about as we see those around us we love die.

***

Richard Barrett lives and works in Salford, UK. His poetry collections are Pig Fervour (Arthur Shilling Press, 2009); Sidings (White Leaf Press, 2010); A Big Apple (Knives Forks and Spoons, 2011); # (zimZalla, 2011); The Shangri Las (erbacce, 2013); with, forthcoming, Free (Blart Books, 2014). His work has been widely anthologized; most recently in Philip Davenport’s The Dark Would. He is a co-organiser of the Manchester based reading series Peter Barlow’s Cigarette.

25 Points: The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry & Poetics, 4th Edition

The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry & Poetics, 4th Edition

The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry & Poetics, 4th Edition

ed. Roland Greene, Stephen Cushman, Clare Cavanagh, and Jahan Ramazani

Princeton University Press, 2012

1680 pages / $49.50 buy from Amazon or Powell’s

1. After graduating from college and while in the process of applying to MFA programs, I bought a copy of The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry & Poetics having come across it in the discount bins of a book retailer down at the local strip mall hell lost somewhere between the suburbs of New Jersey and the rest of Southern California.

2. This was the hardcover 3rd edition published in 1993—previous editions appeared in 1974 and 1963.

3. Out of a total 1100 articles, the new paperback 4th edition presents 250 “entirely new” entries.

4. The Encyclopedia is what’s commonly referred to as a desk reference, i.e., it’s handy to have round.

5. With my 3rd edition I set out to learn EVERYTHING about the reading and writing of poems.

6. I’ve found this a daunting task. Nonetheless, my 3rd edition has been well used over the years.

7. It is a little geeky feeling—but nonetheless stimulating!—to pour over entries, allowing various elements of chance to guide where your floating interests and eyes may take you.

8. A Bibliomancy Tool: righteously applied in the proper MFA program deconditioning environment it just might save a young budding poet or two from the curse of professionalization. Or else it will studiously assist in that very further professionalization.

9. Five types of entries are included: “terms and concepts; genres and forms; periods, schools, and movements; the poetries of nations, regions, disciplines, and social practices such as linguistics, religion, and science.” These “are provisional, and many items could move among them.”

10. “A large number of entries are written by scholars of poetries other than English—a Hispanist on pastoral, a scholar of the French Renaissance on epidexis, a Persianist on panegyric.” READ MORE >

December 17th, 2013 / 6:35 pm

25 Points: Swamp Isthmus

Swamp Isthmus

Swamp Isthmus

by Joshua Marie Wilkinson

Black Ocean, 2013

88 pages / $14.95 buy from Black Ocean

1. I’ve been working on this since this past spring. After reading Beyond The Like Factory & The Hatchet: Rethinking Poetry Reviewing by Joshua Marie Wilkinson, I knew I had to finish this review. This is actually a scary thing to write now.

2. Swamp Isthmus is Joshua Marie Wilkinson’s first book with Black Ocean and the second book in his No Volta pentalogy (first is Selenography, Sidebrow 2010; third will be The Courier’s Archive & Hymnal, Sidebrow 2014). I’ve not read Selenography so there is perhaps some things I’ve missed by not having done so.

3. A swamp is a living-dead landscape; the living feed off of the dead and dying, the most dead areas are filled with the most life and the least dead areas are those with the least life.

From the Hart Crane epigraph (The resigned factions of the dead preside) in the very beginning of Swamp Isthmus, Joshua Marie Wilkinson creates a zombie landscape, a zone that infects the living with symptoms of deadness. In a zombie film this deadness comes to the living with capitalist critiques of our alienating existence, but in Swamp Isthmus we see a zombie that carries critiques of the ecologic and nostalgic sort.

4. The lyrics of Swamp Isthmus are a living-dead endeavor: precise breaks eluding a narrative; linearity reduced to phrases contained in the line.

to disappear you must

tunnel discreet

descrying over nightfall

with unclogged wind

this coast is longer than a train track

needing coarse woolen cloth &

the clothes you’re in

so needing a bad song

to whistle what’s known

but may stick

to another’s mouth

5. Similar to what Zach Savich says about Wilkonson’s lyrics, to kill a zombie takes precision: remove the head, destroy the brain.

6. In The Dead Rustle, The Earth Shudders, Evan Calder Williams points to something that is obvious in Swamp Isthmus:

“…the undead have never really been dead in the first place—they never died.’

7. To cross a swamp takes precision and a mind for the contradiction of the living-dead: step here, not there; eat this, not that; drink plenty of water, but don’t drink the water.

footpaths marked by

false stars

it gathers up in

this bladder of light

8. the trees palsy/ to our bad lines.

9. In some respects, there is an admission with these lines of the failure of poetry to enact this landscape; the lines aren’t good. In some respects it’s proof that poetry works: even the bad lines cause the landscape to shudder.

10. There may be an actual “Swamp Isthmus.” The book’s title might be a reference to Gastineau Channel in Alaska, which at low-tide creates an isthmus from mainland Alaska to Douglas Island. Fritz Cove Road, mentioned in the section, I Go By Edgar Huntly Now, is a road that “dwindles down/to a patch of currants” (note the clever word play on ‘currents’) but it also ends at the place where Gastineau Channel meets Fritz Cove. A place that may eventually be unnavigable by watercraft. A place severely affected by glacial melt/global warming. READ MORE >

December 3rd, 2013 / 5:33 pm

25 Points: Sad Robot Stories

Sad Robot Stories

Sad Robot Stories

by Mason Johnson

CCLaP Publishing, 2013

126 pages / $22.00 ($4.99 Kindle Edition) buy from CCLaP or Amazon

1. What happens when the world goes deaf?

2. Sad Robot Stories by Mason Johnson is a novella about Robot and “his” existential crisis after the collapse of the world, left only with “his” mechanical “brothers” and “sisters” and the usual fire and brimstone of an apocalypse setting.

3. Maybe deaf is the wrong word. Or the wrong cadence. What happens when the sound of humans is extinguished? “Yes, the cries, giggles, laughter, screams, moans of both pain and pleasure, squeals, wails, whispers–the many sounds of the human race–were all gone. Even the minute sound of blood rushing through veins and arteries, speeding through the heart and up to the brain…was gone.” Could you, theoretically, if you didn’t die and weren’t some pile of dust eating radioactivity, I mean, could you handle it?

4. Robot is special or different than his siblings in that his emotional spectrum has for some reason also been anthropomorphized. He is, like the title suggests, sad that the humans are gone.

5. Humans have created (in our world) a null-sound room–which one research team has monikered as a Dead Room–that most scientists call an anechoic chamber, in order to develop and test various auditory waves.

6. “An anechoic chamber (an-echoic meaning non-echoing or echo-free) is a room designed to completely absorb reflections of either sound or electromagnetic waves. They are also insulated from exterior sources of noise. The combination of both aspects means they simulate a quiet open-space of infinite dimension, which is useful when exterior influences would otherwise give false results.” (Wikipedia)

7. Robot specifically misses from the human race Mike and Mike’s nuclear family. Mike was the first human to acknowledge (or perhaps ignore) Robot’s being. “Being” here couples physical and metaphysical, which, according to more Wikipedia, is exactly anathema to Speculative Realism. Speculative Realism, from the one article I read, argues for the multiple possibilities of reality; that no one universal law is stable according to these multiple possibilities (with the exception of the Principle of Non-Contradiction); “there is no reason [the universe] could not be otherwise.” A good ground rule for any Science Fiction.

8. In the anthropocentric world of Robot pre- human extinction, there are workplace laws managing the ratio of humans-to-robots, which presumptuously leads to pay differences, benefits, etc. Like any class distinction, humans have structured a wall to stand on in order to look down upon those below, i.e. robots. Mike plays pool with Robot, takes Robot home to meet his family. He tells Robot stories of his life. He treats “him” like a friend.

9. “Anechoic chambers, a term coined by American acoustics expert Leo Beranek, were originally used in the context of acoustics (sound waves) to minimize the reflections of a room.”

10. Robot is fascinated not just by Mike’s stories of an alcoholic, nihilistic past, but of Mike’s budding fascination and subsequent redemption after Mike started reading books. This notion of the redemptive functions of books/stories is not objective. “And it is true that the tool is the congealed outline of an operation. But it remains on the level of the hypothetical imperative. I may use the hammer to nail up a case or to hit my nieghbour over the head.” (Jean-Paul Sarte, “What Is Literature?”) You read/write a story, why? READ MORE >

November 26th, 2013 / 11:09 am

Interview: The Synchronia Project

The Synchronia Project, slated for release next February, is difficult to define. Not exactly a journal, it is a composite, open-ended literary endeavor that will feature work by multiple authors. But it is not a collaboration between the authors; the only collaboration happening is between editors Emily Kiernan and Joe Trinkle , who will be reading the submissions and arranging them into a larger whole. The end goal remains vague, only because the project is still accepting submissions. It is these submissions that will in large part determine Synchronia’s direction, and Kiernan and Trinkle hope to discover a larger narrative—a feeling of synchronicity—across the selected pieces. I had the opportunity to interview these two and learn more about the project.

***

Dan Hoffman: What was the impetus behind The Synchronia Project? Was there a specific literary influence, or did it evolve from a bigger reading of the collective writing you see as editors and writers?

Joe Trinkle: I think it started by us wanting to create something from other people’s work. We’re both writers who read a fair amount of anthologies and literary journals, and we wanted to do something ambitious, something more than just a collection of stories that we like. I think, somewhere in the back of my head, when I’m reading several simultaneously produced journals, online or in print, I notice how much we are writing about the same things or writing in similar voices, and we wanted to play around with that. To see if a pool of submissions would reflect some kind of pattern.

In a larger sense, some of my favorite novels feel like several broken novellas woven together, stories that would not have had nearly as much effect on a reader by themselves, but somehow add to each other, compliment, enhance each other, even if their plots don’t cross paths. I’m thinking Last Exit to Brooklyn, Infinite Jest, and some of the great short story collections of the twentieth century—those kind of books. I actually just read Cloud Atlas, which is a perfect example of what I was thinking about when Emily and I first discussed this project. I wanted to see what it would be like to try to create a fractured novel like that, but with stories from several writers.

Emily Kiernan: It absolutely had a lot to do with the kind of work we like to read. Fracture has been one of the watchwords of literature since the advent of modernism, and. we grew up as readers and writers in a world where that kind of fallen-apart messiness was a dominant form. Most of our models for what it meant to write about the present world, or for what it meant to approximate our experience, inhabited that kind of cut-up space. So of course we are drawn to these broken narratives. One of the first books I remember Joe and I bonding over was Winesburg, Ohio, which had that distinctly modern novel-in-stories form. It is a flat-out rejection of cohesion. Given this history, I think it is natural that we wanted to extend that form outwards, from the book itself to the magazine or the collection.

One thing that I think is remarkable about The Synchronia Project, though–which actually works against this tradition–is that we’re not fracturing something whole, but rather trying to fit these broken pieces together. Binding up the wounds (a little fragment of language that knocks about in my head).

DH: It seems to me that the closest antecedent to The Synchronia Project actually belongs to the realm of cinema, and not of literature, because even if a single literary text unifies multiple narratives it is still, finally, only written by one author; whereas arguably in cinema there is often no single “author” of the film. How much, if at all, was cinema an inspiration for this project?

JT: I watch an embarrassingly low number of films, so my immediate response would be not much. But I’d argue that even though a book usually has only one author, it often times has many editors; it often goes through the finely cut die of a workshop or an MFA program, and the ideas that are infused into the text partly come from reading the work of others. The idea of “one author” is true, but there are a lot of hands on the text, both directly and indirectly.

EK: I also can’t claim any substantial film knowledge, beyond having watched a few more of them than Joe, so any cinema influence on the project would be indirect. As for the one-author element, there actually is a lot of collaborative writing out there, though I suppose it’s more common in poetry than in fiction. (Can I advertise? I’d like to advertise. A few good friends of mine recently started Bon Aire Projects, which publishes exclusively collaborative work.) Jack Kerouac and William S. Burroughs wrote a novel together called And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks. Supposedly the name came from a news report about a fire at a circus—a fact that haunts me. The poor hippos.

DH: On that note, is there any connection between your ideas on authorship (post-Barthes, post-deconstructionism, etc. etc.) and the spirit of The Synchronia Project? Because it seems to me that such an endeavor must in part emerge from a distinctly contemporary conception of what it means to read and interpret texts. Would you say that, in a sense, this is as much about your interpretation of the submissions as their intrinsic qualities?

EK: I don’t think we are out to make any particular comment on authorship–there still exists more than one valid way to own or not own your work–though I suppose we are exploring one of the little rooms that Barthes et al opened up. We’re mostly a bit over-enthusiastic and a bit over-confident and want really badly to be in on the good stuff we see happening all around us in the writing world, so we manufactured this bribe of publication to get our favorite writers to let us futz with their work. We are, in a sense, asking our favorite authors to put aside their authorship for the duration of this project, to engage in this particular book/journal/what-have-you on different terms. It’s a playful thing at heart, and I want authors to engage in it in that way.

It is also strange and intimate what happens when you ask people to work with you, to be in your circle, in this odd way, and we are interested in that act of unearned generosity or faith. There are always problems with gate-keeping, with editing, with privileging one voice over another, and this project puts pressures on those seams in a way that I hope will be revealing, and that I hope will work.

JT: I listen to/watch many author interviews, and something I’ve noticed is how surprised writers can be by the things that others find in their work. Writing fiction is largely intuitive, I think, as well as the revision process, and while major motifs are often intentional, other aspects of the work just kind of sneak in from the subconscious, or the part of the brain that thinks abstractly, that doesn’t quite focus on words. So when a great book is written, and everybody reads it and then someone sits the author down for an interview, they ask her all of these questions, to which she ends up replying, “Yeah, that just kind of happened,” or “Sure, I can see that.”

In this way, themes seem to emerge that the author is not entirely in control over, and when you look at several works from within a given time period, it’s even easier to draw lines between those unconscious themes. To answer your question: we want to see work that is good, to identify those unintentional unifying themes, and to thread it together with other work with similar sub- or unconscious trajectories.

November 20th, 2013 / 12:00 pm

Three Scenarios in Which Hana Sasaki Grows a Tail: Stories

Three Scenarios in Which Hana Sasaki Grows a Tail: Stories

Three Scenarios in Which Hana Sasaki Grows a Tail: Stories

by Kelly Luce

A Strange Object, 2013

152 pages / $14.95 buy from A Strange Object

1. Three Scenarios in Which Hana Sasaki Grows a Tail is the debut story collection by Kelly Luce.

2. It fits on a bookshelf of modern Japanese writing somewhere between Yoko Ogawa’s Revenge and Banana Yoshimoto, maybe even one shelf up from Haruki Murakami.

3. The only thing is that Kelly Luce grew up in Brookfield, Illinois.

4. How strict is the “write what you know” edict? On Big Think, Nathan Englander reminds us that this advice is too often misconstrued. It really means we should write from a place of emotional familiarity, not that we’re limited to autobiographical writing.

5. But are there limitations when we talk about writers depicting foreign cultures? This story collection seems very Japanese (if a book can even be “very Japanese”) and yet, it’s distinctly American, too.

6. When I was nine I was flipping through channels and caught the end of Akira on basic cable. I had no clue what was going on, but in the weeks, months, and years to follow I found that it left an indelible mark on me—a predilection towards the uncomfortably strange.

7. A Strange Object is the name of the independent press that published Three Scenarios in Which Hana Sasaki Grows a Tail. They’re based out of Austin, TX. This is their first book, too.

8. This is strictly conjecture, but Japanese culture affords for a strangeness that is uniquely its own. Look at all of the Japanese fiction out there: Akutagawa and Mishima, Ryu Murakami and Haruki Murakami, and the scores of manga and J-horror.

9. The characters in Kelly Luce’s collection are outsiders. Many are Americans who move to Japan for work or to connect with the culture that they find so entrancing. Some are only half Asian, an anomaly to the native Japanese—not gaijin, but not Japanese, either. Others are fully Japanese, but do not fit in as with the Japanese school girls who seek refuge from the tedium of their lives through a unique karaoke machine and with the Japanese widower who invented a machine that measures a person’s capacity for love. All are lost. All are searching to fit in.

10. In ninth grade, I ordered a t-shirt with the kanji for gaijin on it. I wore that shirt proudly even though no one at my school in West Tennessee understood what it meant. Looking back, I think I was so drawn to Japanese comic books and cartoons because it was a way to embrace my otherness as a nerdy, awkward white boy. READ MORE >

November 14th, 2013 / 11:14 am

25 Points: A High Wind in Jamaica

A High Wind in Jamaica

A High Wind in Jamaica

by Richard Hughes

NYRB Classics, 1999

279 pages / $14.00 buy from NYRB or Amazon

1. On the surface, Richard Hughes’s A High Wind in Jamaica is a dot-to-dot adventure tale. After a hurricane hits an English settlement in Jamaica, two families decide to send their children back to England. Early on in the voyage the children are taken aboard a pirate ship whereupon they visit exotic ports and busy themselves with imaginary games. They are eventually returned home, and the pirates’ subsequent arrest, trial, and execution rounds out the proceedings. Of course, that last part seems a little extreme and out of place, and that’s really the book’s program, because simmering just below this surface is the constant threat of rape and murder.

2. In the spirit of Calvino’s later lecture on lightness versus weight, the narrative manages to float just above the threat of violence. You get the feeling after a while that Hughes is totally aware that you’re aware of the divide between high adventure and childhood trauma, and so he starts to fuck with your sense that awful things need to happen.

3. And, of course, awful things do happen—often and with startling frankness—but they are always quickly buried under the book’s relentless trend towards lightness.

4. The earliest memory I have is of staring up at the bottom of a kitchen table. I don’t know where I was or what I was doing, but I remember looking at a pattern in the wood and then turning toward a doorway. That’s it. I know I’ve told the memory differently over the years, adding in details about toys or sounds or maybe a smell wafting in, but the truth is that I just have this one scant moving image. I don’t think it’s a lie to embellish something so bland and colorless in texture, and at certain points I might have really believed in the additions.

5. Before I reread the novel to work on this review, I kept thinking it opened with a bigger feint at being a lighthearted adventure, but this is totally wrong. By the end of the first chapter’s scene-setting, two colonial ladies starve to death (or are fed ground-up glass by their servants, who knows!), a black servant drowns in a bathing pool, and countless rats and bats are dispatched by the family’s cat. All the while, we’re reminded that this is “a kind of paradise for English children to come to.” Right.

6. I usually skip introductions, but when I talk about AHWiJ, I almost always fall back on Francine Prose’s brief intro for the NYRB edition: “First the vague premonitory chill—familiar, seductive, unwelcome—then the syrupy aura coating the visible world, through which its colors and edges appear ever more lurid and sharp… The experience of reading Richard Hughes’s A High Wind in Jamaica…evokes the somatic sensations of falling ill, as a child.” Sign me up.

7. Another big theme of the book’s opening is the whole colonial question, which is vital and pressing and could probably be handled with greater finesse than I can muster here. Suffice it to say that the first sentence presents ruined slave quarters, sugar-grinding houses, and mansions, all “fruits of Emancipation in the West Indies.” Considering the adventure-story-through-a-fun-house-mirror about to come, it’s hard not to think that this kind of stage-setting is about just rewards, that the English family deserves everything that’s about to come.

8. A brief digression cum recipe: AHWiJ allegedly contains the first mention of a drink called the Hangman’s Blood—a mixture of rum, gin, brandy, and porter—“innocent (merely beery) as it looks, refreshing as it tastes, it has the property of increasing rather than allaying thirst, and so once it has made a breach, soon demolishes the whole fort.” Clearly the kind of mix that leads to public exposure and pissing blood and, of course, piracy.

9. Is there actually such a thing as an anti-adventure novel? (I’d imagine something like Coetzee’s Foe might come close, although its meta-narrative seems more about deconstructing the adventure genre than teasing out its hidden desires.) And furthermore, if there were such an anti-genre, would it stand in opposition to all of the finicky colonial and gender and race problems inherent in Defoe and Dumas and Stevenson? While AHWiJ is never really a wholehearted rejection of the adventure novel’s Victorian and Enlightenment-era point of view, the ways in which it represses and then inverts these views are extremely sneaky and, by the book’s end, terrifying.

10. The narrative portrays the adult world as a haze of concealed motives and consequences. A pirate’s drunken leer and a parent’s concern over a coming hurricane are met with the same curious misapprehension: that something vital or alarming is just beyond one’s young recognition. But while Hughes draws a kind of tight circular POV around the children, he also lets the reader step out into the larger circle of this adult world, and somewhere between the larger circle and the nested one is a place where motives and the threat of their attendant consequences exist. READ MORE >

November 12th, 2013 / 2:14 pm

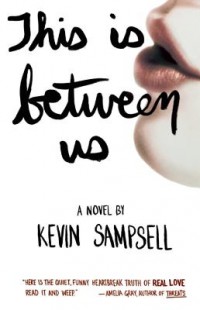

25 Points: This Is Between Us

This Is Between Us

This Is Between Us

by Kevin Sampsell

Tin House Books, 2013

240 pages / $15.95 buy from Powell’s or Amazon

1. This book reminded me of this remix which was incredibly moving and pained me this spring and still pains me now http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0KbdOBE1ORw

2. The thing about Kevin Sampsell is that he feels like the kind of guy who has been through everything. He’s just one of those people. He doesn’t have that used up feeling or look at all but he does have that vibe of being the kind of guy who has lived through basically everything there is as a human to experience but not in a hardened way.

3. I’m not explaining this right but he’s just one of those people who seems complicated and well adjusted and like if you talk to him he just has been there, whatever it is but he doesn’t come outright and say that instead he just comes from this I know what you mean mode which isn’t even patronizing the point here is that all of that also comes through in his writing and this book This Is Between Us from Tin House coming out is five years of a life.

4. Anything you have ever experienced in your life is in this book.

5. This book is comforting.

6. Sometimes this book is upsetting.

7. This book is comforting.

8. Some people said this book was disturbing and I was like have you ever lived your life at all or ever really loved someone or had a partner and if you haven’t maybe your life is easier and even if your life has been really nice you’ll still be like “yup” while reading parts of this book because it’s just so real in how it’s rendered because it’s just written so elegantly and simply stated and maybe that’s the thing with Kevin Sampsell’s writing.

9. We’re working with the rhetorical you in this entire book.

10. It’s written like a confessional ode-ish poem. READ MORE >

November 7th, 2013 / 1:06 pm