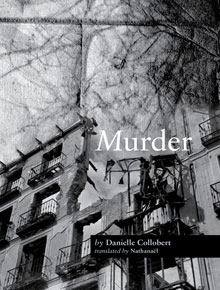

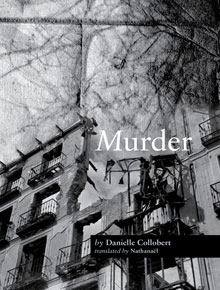

Forthcoming from Litmus Press this April, Nathanaël’s definitive English translation of Danielle Collobert’s Murder marks the first ever of this French poet’s debut book. Originally begun in 1960 when Collobert was twenty years old, and published by Gallimard in 1964 under the auspices of Oulipo-founder, Raymond Queneau, this book laid the groundwork for what remains one of the most enigmatic and innovative bodies of work in contemporary French letters. As with the subsequent works of Collobert’s brief but impactful output, which lasted until her suicide in 1978, Murder speaks a language profoundly its own, unlike anything else she was to write, and quite possibly unlike anything else you may have read. Reading this prose gives one the rare impression of being in the presence of a voice speaking from the honest and cutting edge of present urgencies: that is, this is not a voice responding to conventions or trends in literary necessity, but one singularly engaging the emergent necessities of life itself, in all its complexity and danger. Here, in honor of Danielle Collobert and this fantastic new translation, Nathanaël and I discuss her life and legacy with an eye on her first work, Murder.

***

Murder

Murder

by Danielle Collobert / translated by Nathanaël

Litmus Press, April 2013

104 pages / $18 Buy from Litmus Press or SPD

Kit Schluter: To begin, what drew you to Danielle Collobert’s work? How did you discover it?

Nathanaël: I want to say that it was accidental, but I’m quite sure it wasn’t. Unless one understands friendship as accident. I entered, as did many, into Il donc, and Collobert’s Carnets, though with an eye turned away – perhaps out of a desire not to seek the life in the work, however much it is written there, and with such determinacy; the ‘twenty years of writing’ set against the impending suicide. Still, it is a hazard of hindsight to be able to set the life against the work, though this is so obviously a deformation of the reader, and so I resist as much as I can the tidy narrative of a life fallen from letters. The short answer to your first question is: Collobert’s language. But if the virtuosic remnants of Il donc are almost a perfect epitaph to the twenty years, I was much more viscerally and immediately impelled by Meurtre; I even borrowed an epigraph from this work into We Press Ourlseves Plainly much before the idea even of translating it had presented itself to me. Perhaps most immediately because of a shared concern, or conviction, that the distinction between murder and death is unconvincing and too readily upheld.

KS: What were the circumstances surrounding Danielle Collobert while she was composing Murder? Do you find that the book draws material or imagery from her experience?

N: My knowledge of Collobert’s biography is quite limited. Not unlike her parents and her aunt, who were all actively engaged in the Résistance during WWII, Collobert, a supporter of Algerian independence, was a member of the FLN (Algeria’s Front de libération national) at the time of Meurtre. She chose exile in Italy, where she completed work on the manuscript. It may be worth underscoring the importance of 1961, for the outcome of the war, which, in French contemporary society was never acknowledged under the name of anything other than the euphemistic “les évènements” (“the events” – to do otherwise would have been, not only to have acknowledged, if only semantically, Algeria’s nationhood, but the repressive force employed by France to resist – and as it happened, to defer – decolonization and independence). On October 17, 1961, a peaceful demonstration of many thousands of Algerians living in Paris, protesting the curfew imposed exclusively upon them, and the acts of police violence to which they were systematically subjected, was violently suppressed by Vichyist Maurice Papon’s police force, resulting in the arbitrary deportation of large numbers of Algerian demonstrators, and the summary execution of up to two hundred Algerians, many of whose bodies were pulled out of the Seine in the following days; several thousand Algerians were rounded up during the demonstration and distributed among prisons, the Palais des Sports and area hospitals. Several months later, on February 8th, 1962, what has come to be known as the Charonne Massacre took place at the eponymous Paris métro station; this demonstration, organized by the Left against the paramilitary OAS (the reactionary Organisation de l’armée secrète, which violently opposed Algerian independence), and often conflated in people’s memories (and in historical accounts) with the October massacre, resulted in the death of eight demonstrators at the Charonne métro station. It is not insignificant that French FLN supporter Jacques Panijel’s 1961 film, Octobre à Paris, which documents the moments before, during, and after the October demonstration, was censured by the French government and only shown for the first time in a French cinema in 2011 – half a century after it was made.

The photograph on the cover of Murder accounts, obliquely, and somewhat prochronistically, for these activities – it is a photograph of a bombed out building in Madrid, taken in 1937 by Robert Capa, during the Spanish Civil War.

Meurtre is tempered by the residues of such histories; but the work’s strength is in its ability to evoke them without resorting to explicit accounts, or naming. The generalization of historical violence is embedded in the intimate accounts presented to the reader – seemingly placeless, nameless, they nonetheless achieve historical exactitude through relentless repetition – a reiterative (mass) murder (one is tempted to say: execution), which afflicts and incriminates the gutted bodies that move painstakingly through these densely succinct pages.

READ MORE >

How Literature Saved My Life

How Literature Saved My Life

Reliquary

Reliquary Triste, Mourning Stories

Triste, Mourning Stories